RC Transients Circuits Having Capacitors: • at DC – Capacitor Is an Open Circuit, Like It’S Not There

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Timing of Load Switches

Application Report SLVA883–April 2017 Timing of Load Switches Nicholas Carley........................................................................................................... Power Switches ABSTRACT Timing of load switches can vary depending on the operating conditions of the system and feature set of the device. At a glance, these variations can seem complex; but, when broken down, each operating condition and feature has a correlation to a change in timing. This application note goes into detail on how each condition or feature can alter the timing of a load switch so that the variations can be prepared for. Contents 1 Overview and Main Questions ............................................................................................. 2 1.1 Definition of Timing Parameters .................................................................................. 2 1.2 Alternative Timing Methods ....................................................................................... 2 1.3 Why is My Rise Time Different than Expected? ................................................................ 3 1.4 Why is My Fall Time Different than Expected? ................................................................. 3 1.5 Why Do NMOS and PMOS Pass FETs Affect Timing Differently?........................................... 3 2 Effect of System Operating Specifications on Timing................................................................... 5 2.1 Temperature........................................................................................................ -

System Step and Impulse Response Lab 04 Bruce A

ROSE-HULMAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering ECE 300 Signals and Systems Spring 2009 System Step and Impulse Response Lab 04 Bruce A. Ferguson, Bob Throne In this laboratory, you will investigate basic system behavior by determining the step and impulse response of a simple RC circuit. You will also determine the time constant of the circuit and determine its rise time, two common figures of merit (FOMs) for circuit building blocks. Objectives 1. Design an experiment by specifying a test setup, choosing circuit component values, and specifying test waveform details to investigate the step and impulse response. 2. Measure the step response of the circuit and determine the rise time, validating your theoretical calculations. 3. Measure the impulse response of the circuit and determine the time constant, validating your theoretical calculations. Prelab Find and bring a circuit board to the lab so you can build the RC circuit. Background As we introduce the study of systems, it will be good to keep the discussion well grounded in the circuit theory you have spent so much of your energy learning. An important problem in modern high speed digital and wideband analog systems is the response limitations of basic circuit elements in high speed integrated circuits. As simple as it may seem, the lowly RC lowpass filter accurately models many of the systems for which speed problems are so severe. There is a basic need to be able to characterize a circuit independent of its circuit design and layout in order to predict its behavior. Consider the now-overly-familiar RC lowpass filter shown in Figure 1. -

Chapter 4 HW Solution

ME 380 Chapter 4 HW February 27, 2012 Chapter 4 HW Solution Review Questions. 1. Name the performance specification for first order systems. Time constant τ. 2. What does the performance specification for a first order system tell us? How fast the system responds. 5. The imaginary part of a pole generates what part of the response? The un-decaying sinusoidal part. 6. The real part of a pole generates what part of the response? The decay envelope. 8. If a pole is moved with a constant imaginary part, what will the responses have in common? Oscillation frequency. 9. If a pole is moved with a constant real part, what will the responses have in common? Decay envelope. 10. If a pole is moved along a radial line extending from the origin, what will the responses have in common? Damping ratio (and % overshoot). 13. What pole locations characterize (1) the underdamped system, (2) the overdamped system, and (3) the critically damped system? 1. Complex conjugate pole locations. 2. Real (and separate) pole locations. 3. Real identical pole locations. 14. Name two conditions under which the response generated by a pole can be neglected. 1. The pole is \far" to the left in the s-plane compared with the other poles. 2. There is a zero very near to the pole. Problems. Problem 2(a). This is a 1st order system with a time constant of 1/5 second (or 0.2 second). It also has a DC gain of 1 (just let s = 0 in the transfer function). The input shown is a unit step; if we let the transfer function be called G(s), the output is input × transfer function. -

Effect of Source Inductance on MOSFET Rise and Fall Times

Effect of Source Inductance on MOSFET Rise and Fall Times Alan Elbanhawy Power industry consultant, email: [email protected] Abstract The need for advanced MOSFETs for DC-DC converters applications is growing as is the push for applications miniaturization going hand in hand with increased power consumption. These advanced new designs should theoretically translate into doubling the average switching frequency of the commercially available MOSFETs while maintaining the same high or even higher efficiency. MOSFETs packaged in SO8, DPAK, D2PAK and IPAK have source inductance between 1.5 nH to 7 nH (nanoHenry) depending on the specific package, in addition to between 5 and 10 nH of printed circuit board (PCB) trace inductance. In a synchronous buck converter, laboratory tests and simulation show that during the turn on and off of the high side MOSFET the source inductance will develop a negative voltage across it, forcing the MOSFET to continue to conduct even after the gate has been fully switched off. In this paper we will show that this has the following effects: • The drain current rise and fall times are proportional to the total source inductance (package lead + PCB trace) • The rise and fall times arealso proportional to the magnitude of the drain current, making the switching losses nonlinearly proportional to the drain current and not linearly proportional as has been the common wisdom • It follows from the above two points that the current switch on/off is predominantly controlled by the traditional package's parasitic -

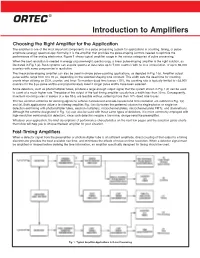

Introduction to Amplifiers

ORTEC ® Introduction to Amplifiers Choosing the Right Amplifier for the Application The amplifier is one of the most important components in a pulse processing system for applications in counting, timing, or pulse- amplitude (energy) spectroscopy. Normally, it is the amplifier that provides the pulse-shaping controls needed to optimize the performance of the analog electronics. Figure 1 shows typical amplifier usage in the various categories of pulse processing. When the best resolution is needed in energy or pulse-height spectroscopy, a linear pulse-shaping amplifier is the right solution, as illustrated in Fig. 1(a). Such systems can acquire spectra at data rates up to 7,000 counts/s with no loss of resolution, or up to 86,000 counts/s with some compromise in resolution. The linear pulse-shaping amplifier can also be used in simple pulse-counting applications, as depicted in Fig. 1(b). Amplifier output pulse widths range from 3 to 70 µs, depending on the selected shaping time constant. This width sets the dead time for counting events when utilizing an SCA, counter, and timer. To maintain dead time losses <10%, the counting rate is typically limited to <33,000 counts/s for the 3-µs pulse widths and proportionately lower if longer pulse widths have been selected. Some detectors, such as photomultiplier tubes, produce a large enough output signal that the system shown in Fig. 1(d) can be used to count at a much higher rate. The pulse at the output of the fast timing amplifier usually has a width less than 20 ns. -

Equivalent Rise Time for Resonance in Power/Ground Noise Estimation

Equivalent Rise Time for Resonance in Power/Ground Noise Estimation Emre Salman, Eby G. Friedman Radu M. Secareanu, Olin L. Hartin Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering Freescale Semiconductor University of Rochester MMSTL Rochester, New York 14627 Tempe, Arizona 85284 [salman, friedman]@ece.rochester.edu [r54143,lee.hartin]@freescale.com R p L p Abstract— The non-monotonic behavior of power/ground noise ΔnVdd− with respect to the rise time tr is investigated for an inductive power distribution network with a decoupling capacitor. A time I (t) L (I swi ) p domain solution is provided for the rise time that produces C resonant behavior, thereby maximizing the power/ground noise. d I C (t) I swi The sensitivity of the ground noise to the decoupling capacitance V dd Cd and parasitic inductance Lg is evaluated as a function of R d the rise time. Increasing the decoupling capacitance is shown (t r ) i to efficiently reduce the noise for tr ≤ 2 LgCd. Alternatively, reducing the parasitic inductance Lg is shown to be effective for Δ ≥ n tr 2 LgCd. R g L g I. INTRODUCTION Fig. 1. Equivalent circuit model to estimate power supply noise and ground The distribution of robust power supply and ground voltages bounce. Rp, Lp, and Rg, Lg represent the power and ground rail impedances, is a challenging task in modern integrated circuits due to scaled respectively. Cd is the decoupling capacitor and Rd is the effective series resistance (ESR) of the capacitor. The load circuit is represented by a current power supply voltages and the increased switching activity of source with a rise time (tr)i and peak current (Iswi)p. -

Cutoff Frequency, Lightning, RC Time Constant, Schumann Resonance, Spherical Capacitance

International Journal of Theoretical and Mathematical Physics 2019, 9(5): 121-130 DOI: 10.5923/j.ijtmp.20190905.01 Solar System Electrostatic Motor Theory Greg Poole Industrial Tests, Inc., Rocklin, CA, United States Abstract In this paper, the solar system has been visualized as an electrostatic motor for the research of scientific concepts. The Earth and space have all been represented as spherical capacitors to derive time constants from simple RC theory. Using known wave impedance values (R) from antenna theory and celestial capacitance (C) several time constants are derived which collectively represent time itself. Equations from Electro Relativity are verified using known values and constants to confirm wave impedance values are applicable to the earth antenna. Dark energy can be represented as a tremendous capacitor voltage and dark matter as characteristic transmission line impedance. Cosmic energy transfer may be limited to the known wave impedance of 377 Ω. Harvesting of energy wirelessly at the Earth’s surface or from the Sun in space may be feasible by matching the power supply source impedance to a load impedance. Separating the various the three fields allows us to see how high-altitude lightning is produced and the earth maintains its atmospheric voltage. Spacetime, is space and time, defined by the radial size and discharge time of a spherical or toroid capacitor. Keywords Cutoff Frequency, Lightning, RC Time Constant, Schumann Resonance, Spherical Capacitance the nearest thimble, and so put the wheel in motion; that 1. Introduction thimble, in passing by, receives a spark, and thereby being electrified is repelled and so driven forwards; while a second In 1749, Benjamin Franklin first invented the electrical being attracted, approaches the wire, receives a spark, and jack or electrostatic wheel. -

Module 4: Time Response of Discrete Time Systems Lecture Note 1

DigitalControl Module4 Lecture1 Module 4: Time Response of discrete time systems Lecture Note 1 1 Time Response of discrete time systems Absolute stability is a basic requirement of all control systems. Apart from that, good relative stability and steady state accuracy are also required in any control system, whether continuous time or discrete time. Transient response corresponds to the system closed loop poles and steady state response corresponds to the excitation poles or poles of the input function. 1.1 Transient response specifications In many practical control systems, the desired performance characteristics are specified in terms of time domain quantities. Unit step input is most commonly used in analysis of a system since it is easy to generate and represent a sufficiently drastic change thus providing useful informa- tion on both transient and steady state responses. The transient response of a system depends on the initial conditions. It is a common prac- tice to consider the system initially at rest. Consider the digital control system shown in Figure1. r(t) e(t) c(t) c(kT) Digital Hold Plant + − Controller T T Figure 1: Block Diagram of a closed loop digital system Similar to the continuous time case, transient response of a digital control system can also be characterized by the following. 1. Rise time (tr): Time required for the unit step response to rise from 0% to 100% of its final value in case of underdamped system or 10% to 90% of its final value in case of overdamped system. 2. Delay time (td): Time required for the the unit step response to reach 50% of its final value. -

CMOS Digital Integrated Circuits

CMOS Digital Integrated Circuits Chapter 5 MOS Inverters: Static Characteristics Y. Leblebici 1 Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Permission required for reproduction or display. Ideal Inverter Voltage Transfer Characteristic (VTC) of the ideal inverter 2 1 Generic Inverter VTC Voltage Transfer Characteristic (VTC) of a typical inverter 3 Noise Margins Propagation of digital signals under the influence of noise VOH : VOUT,MAX when the output level is logic "1“ VOL : VOUT,MIN when the output level is logic "0“ VIL : VIN,MAX which can be interpreted as logic "0“ VIH : VIN,MIN which can be interpreted as logic "1" 4 2 Noise Margins Definition of noise margins 5 Noise Margins 6 3 Noise Margins Nominal output Output under noise The nominal operating region is defined as the region where the gain is less than unity ! 7 CMOS Inverter Circuit 8 4 CMOS Inverter Circuit The NMOS switch transmits the logic 0 level to the output, while the PMOS switch transmits the logic 1 level to the output, depending on the input signal polarity. 9 CMOS Inverter Circuit 10 5 CMOS Inverter Circuit 11 CMOS Inverter Circuit determine noise margins inversion (switching) threshold voltage 12 6 CMOS Inverter Circuit nMOS transistor current-voltage characteristics 13 CMOS Inverter Circuit pMOS transistor current-voltage characteristics 14 7 CMOS Inverter Circuit Intersection of current-voltage surfaces of nMOS and pMOS transistors 15 CMOS Inverter Circuit Intersection of current-voltage surfaces gives the VTC in the voltage plane 16 8 CMOS Inverter Circuit 17 CMOS Inverter Circuit How to choose the kR ratio to achieve a desired inversion threshold voltage: 18 9 CMOS Inverter Circuit 19 Supply Voltage Scaling VTC of a CMOS inverter for different power supply voltage values. -

Review: Step Response of 1St Order Systems

Review: step response of 1st order systems Step response in the s—domain c(t) 1 steady state Initial slope = = a (final value) a time constant ; s(s + a) 1.0 0.9 in the time domain 0.8 at 1 − e− u(t); 0.7 63% of final value ¡time constant¢ 0.6 at t = one time constant 0.5 1 τ = ; 0.4 a 0.3 rise time (10%→90%) 0.2 2.2 0.1 Tr = ; a 0 t 1 2 3 4 5 settling time (98%) a a a a a Tr 4 T = . Ts s a Figure 4.3 Figure by MIT OpenCourseWare. 2.004 Fall ’07 Lecture 07 – Wednesday, Sept. 19 Review: poles, zeros, and the forced/natural responses jω jω system pole – input pole – system zero – natural response forced response derivative & amplification σ σ −5 0 −5 −2 0 2.004 Fall ’07 Lecture 07 – Wednesday, Sept. 19 Goals for today • Second-order systems response – types of 2nd-order systems • overdamped • underdamped • undamped • critically damped – transient behavior of overdamped 2nd-order systems – transient behavior of underdamped 2nd-order systems – DC motor with non-negligible impedance • Next lecture (Friday): – examples of modeling & transient calculations for electro-mechanical 2nd order systems 2.004 Fall ’07 Lecture 07 – Wednesday, Sept. 19 DC motor system with non-negligible inductance Recall combined equations of motion LsI(s)+RI(s)+KvΩ(s)=Vs(s) ⇒ JsΩ(s)+bΩ(s)=KmI(s) ) LJ Lb KmKv Km s2 + + J s + b + Ω(s)= V (s) R R R R s ⎧ · µ ¶ µ ¶¸ ⎨⎪ (Js + b) Ω(s)=KmI(s) ⎩⎪ Including the DC motor’s inductance, we find Ω(s) Km 1 = Vs(s) LJ b R bR + KmKv ⎧ s2 + + s + Quadratic polynomial denominator ⎪ J L LJ Second—order system ⎪ µ ¶ µ ¶ ⎪ ⎪ ⎪ b ⎪ s + ⎨ I(s) 1 J = µ ¶ ⎪ Vs(s) R b R bR + K K ⎪ 2 m v ⎪ s + + s + ⎪ J L LJ ⎪ µ ¶ µ ¶ ⎪ ⎩⎪ 2.004 Fall ’07 Lecture 07 – Wednesday, Sept. -

Illustration of the Concepts of System Bandwidth and Rise Time Through the Analysis of a First Order CT Low Pass Filter Bandwidth and Risetime

Illustration of the concepts of system bandwidth and rise time through the analysis of a first order CT low pass filter Bandwidth and Risetime Rise time is an easily measured parameter that provides considerable insight into the potential pitfalls in performing a measurement or designing a circuit. Rise time is defined as the time it takes for a signal to rise (or fall for fall time) from 10% to 90% of its final value. A useful relationship between rise time and bandwidth is given by Recognizing that for a simple RC circuit f3dB = (2πRC)-1, this is equivalent to First Order Low pass Filter A low-pass filter is a filter that passes signals with a frequency lower than a certain cutoff frequency and attenuates signals with frequencies higher than the cutoff frequency. The amount of attenuation for each frequency depends on the filter design. The filter is sometimes called a high-cut filter, or treble cut filter in audio applications. A low-pass filter is the opposite of a high-pass filter. A band-pass filter is a combination of a low-pass and a high-pass filter. Low-pass filters exist in many different forms, including electronic circuits (such as a hiss filter used in audio), anti- aliasing filters for conditioning signals prior to analog-to-digital conversion, digital filters for smoothing sets of data, acoustic barriers, blurring of images, and so on. The moving average operation used in fields such as finance is a particular kind of low-pass filter, and can be analyzed with the same signal processing techniques as are used for other low-pass filters. -

Block Diagrams, Feedback and Transient Response Specifications

Block Diagrams, Feedback and Transient Response Specifications This module introduces the concepts of system block diagrams, feedback control and transient response specifications which are essential concepts for control design and analysis. (This command loads the functions required for computing Laplace and Inverse Laplace transforms. For more information on Laplace transforms, see the Laplace Transforms and Transfer Functions module.) Block Diagrams and Feedback Consider the example of a common household heating system. A household heating system usually consists of a thermostat that measures the room temperature and compares it with an input desired temperature. If the measured temperature is lower than the desired temperature, the thermostat sends a signal that opens the gas valve and starts the combustion in the furnace. The heat from the furnace is then transferred to the rooms of the house which causes the air temperature in the rooms to rise. Once the measured room temperature exceeds the desired temperature by a certain amount, the thermostat turns off the furnace and the cycle repeats. This is an example of a control system and in this case the variable being controlled is the room temperature. This system can be sub-divided into its major parts and represented by the following diagram which shows the directions of information flow. This type of diagram, known as a block diagram, is very useful in understanding how the different components interact and effect the variable of interest. Fig. 1: Block diagram of a household heating system The gas valve, furnace and house can be combined to get one block which can be called the plant of the system.