Meinmahla Kyun Wildlife Sanctuary Conservation Programme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yangon University of Economics Department of Commerce Master of Banking and Finance Programme

YANGON UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE MASTER OF BANKING AND FINANCE PROGRAMME INFLUENCING FACTORS ON FARM PERFORMANCE (CASE STUDY IN BOGALE TOWNSHIP, AYEYARWADY DIVISION) KHET KHET MYAT NWAY (MBF 4th BATCH – 30) DECEMBER 2018 INFLUENCING FACTORS ON FARM PERFORMANCE CASE STUDY IN BOGALE TOWNSHIP, AYEYARWADY DIVISION A thesis summited as a partial fulfillment towards the requirements for the Degree of Master of Banking and Finance (MBF) Supervised By : Submitted By: Dr. Daw Tin Tin Htwe Ma Khet Khet Myat Nway Professor MBF (4th Batch) - 30 Department of Commerce Master of Banking and Finance Yangon University of Economics Yangon University of Economics ABSTRACT This study aims to identify the influencing factors on farms’ performance in Bogale Township. This research used both primary and secondary data. The primary data were collected by interviewing with farmers from 5 groups of villages. The sample size includes 150 farmers (6% of the total farmers of each village). Survey was conducted by using structured questionnaires. Descriptive analysis and linear regression methods are used. According to the farmer survey, the household size of the respondent is from 2 to 8 members. Average numbers of farmers are 2 farmers. Duration of farming experience is from 11 to 20 years and their main source of earning is farming. Their living standard is above average level possessing own home, motorcycle and almost they owned farmland and cows. The cultivated acre is 30 acres maximum and 1 acre minimum. Average paddy yield per acre is around about 60 bushels per acre for rainy season and 100 bushels per acre for summer season. -

ANNEX 12C: PROFILE of MA SEIN CLIMATE SMART VILLAGE International Institute of Rural Reconstruction; ;

ANNEX 12C: PROFILE OF MA SEIN CLIMATE SMART VILLAGE International Institute of Rural Reconstruction; ; © 2018, INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE OF RURAL RECONSTRUCTION This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction, provided the original work is properly credited. Cette œuvre est mise à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode), qui permet l’utilisation, la distribution et la reproduction sans restriction, pourvu que le mérite de la création originale soit adéquatement reconnu. IDRC Grant/ Subvention du CRDI: 108748-001-Climate and nutrition smart villages as platforms to address food insecurity in Myanmar 33 IDRC \CRDl ..m..»...u...».._. »...m...~ c.-..ma..:«......w-.«-.n. ...«.a.u CLIMATE SMART VILLAGE PROFILE Ma Sein Village Bogale Township, Ayeyarwaddy Region 2 Climate Smart Village Profile Introduction Myanmar is the second largest country in Southeast Asia bordering Bangladesh, Thailand, China, India, and Laos. It has rich natural resources – arable land, forestry, minerals, natural gas, freshwater and marine resources, and is a leading source of gems and jade. A third of the country’s total perimeter of 1,930 km (1,200 mi) is coastline that faces the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea. The country’s population is estimated to be at 60 million. Agriculture is important to the economy of Myanmar, accounting for 36% of its economic output (UNDP 2011a), a majority of the country’s employment (ADB 2011b), and 25%–30% of exports by value (WB–WDI 2012). -

Appendix 6 Satellite Map of Proposed Project Site

APPENDIX 6 SATELLITE MAP OF PROPOSED PROJECT SITE Hakha Township, Rim pi Village Tract, Chin State Zo Zang Village A6-1 Falam Township, Webula Village Tract, Chin State Kim Mon Chaung Village A6-2 Webula Village Pa Mun Chaung Village Tedim Township, Dolluang Village Tract, Chin State Zo Zang Village Dolluang Village A6-3 Taunggyi Township, Kyauk Ni Village Tract, Shan State A6-4 Kalaw Township, Myin Ma Hti Village Tract and Baw Nin Village Tract, Shan State A6-5 Ywangan Township, Sat Chan Village Tract, Shan State A6-6 Pinlaung Township, Paw Yar Village Tract, Shan State A6-7 Symbol Water Supply Facility Well Development by the Procurement of Drilling Rig Nansang Township, Mat Mon Mun Village Tract, Shan State A6-8 Nansang Township, Hai Nar Gyi Village Tract, Shan State A6-9 Hopong Township, Nam Hkok Village Tract, Shan State A6-10 Hopong Township, Pawng Lin Village Tract, Shan State A6-11 Myaungmya Township, Moke Soe Kwin Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region A6-12 Myaungmya Township, Shan Yae Kyaw Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region A6-13 Labutta Township, Thin Gan Gyi Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region Symbol Facility Proposed Road Other Road Protection Dike Rainwater Pond (New) : 5 Facilities Rainwater Pond (Existing) : 20 Facilities A6-14 Labutta Township, Laput Pyay Lae Pyauk Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region A6-15 Symbol Facility Proposed Road Other Road Irrigation Channel Rainwater Pond (New) : 2 Facilities Rainwater Pond (Existing) Hinthada Township, Tha Si Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region A6-16 Symbol Facility Proposed Road Other Road -

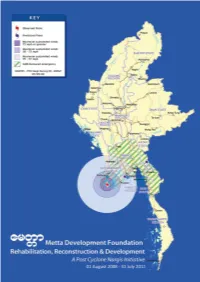

Rehabilitation, Reconstruction & Development a Post Cyclone Nargis Initiative

Rehabilitation, Reconstruction & Development A Post Cyclone Nargis Initiative 1 2 Metta Development Foundation Table of Contents Forward, Executive Director 2 A Post Cyclone Nargis Initiative - Executive Summary 6 01. Introduction – Waves of Change The Ayeyarwady Delta 10 Metta’s Presence in the Delta. The Tsunami 11 02. Cyclone Nargis –The Disaster 12 03. The Emergency Response – Metta on Site 14 04. The Global Proposal 16 The Proposal 16 Connecting Partners - Metta as Hub 17 05. Rehabilitation, Reconstruction and Development August 2008-July 2011 18 Introduction 18 A01 – Relief, Recovery and Capacity Building: Rice and Roofs 18 A02 – Food Security: Sowing and Reaping 26 A03 – Education: For Better Tomorrows 34 A04 – Health: Surviving and Thriving 40 A05 – Disaster Preparedness and Mitigation: Providing and Protecting 44 A06 – Lifeline Systems and Transportation: The Road to Safety 46 Conclusion 06. Local Partners – The Communities in the Delta: Metta Meeting Needs 50 07. International Partners – The Donor Community Meeting Metta: Metta Day 51 08. Reporting and External Evaluation 52 09. Cyclones and Earthquakes – Metta put anew to the Test 55 10. Financial Review 56 11. Beyond Nargis, Beyond the Delta 59 12. Thanks 60 List of Abbreviations and Acronyms 61 Staff Directory 62 Volunteers 65 Annex 1 - The Emergency Response – Metta on Site 68 Annex 2 – Maps 76 Annex 3 – Tables 88 Rehabilitation, Reconstruction & Development A Post Cyclone Nargis Initiative 3 Forword Dear Friends, Colleagues and Partners On the night of 2 May 2008, Cyclone Nargis struck the delta of the Ayeyarwady River, Myanmar’s most densely populated region. The cyclone was at the height of its destructive potential and battered not only the southernmost townships but also the cities of Yangon and Bago before it finally diminished while approaching the mountainous border with Thailand. -

Township Environmental Assessment 2017

LABUTTA TOWNSHIP ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT 2017 MYANMAR ENVIRONMENT INSTITUTE This report has been prepared by Myanmar Environment Institute as part of BRACED Myanmar Consortium(2015-2017) Final Report Page I Abbreviation and Acronyms BRACED Building Resilience and Adaptation to Climate Extremes and Disasters CRA Community Risk Assessment CSO Civil Society Organization CSR Corporate Social Responsibility ECD Environmental Conservation Department EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EMP Environmental Management Plan EU European Union IEE Initial Environmental Examination Inh/km2 Inhabitant per Kilometer Square KBA Key Biodiversity Area MEI Myanmar Environment Institute MIMU Myanmar Information Management Unit MOECAF Ministry of Environmental Conservation and Forestry MONREC Ministry of Natural Resource and Environmental Conservation NCEA National Commission for Environmental Affair NGO Non-Governmental Organization RIMES Regional Integrated Multi -Hazard Early Warning System SEA Strategic Environmental Assessment TDMP Township Disaster Management Plan TEA Township Environmental Assessment TSP Township Final Report Page II Table of Content Executive Summary ______________________________________________ 1 Chaper 1 Introduction and Background ____________________________ 12 1. 1 Background __________________________________________________________________ 12 1. 2 Introduction of BRACED ________________________________________________________ 13 1. 3 TEA Goal and Objective ________________________________________________________ 15 1. 4 SEA -

State Counsellor Stresses Diversity, Rule of Law Daw Aung San Suu Kyi Addresses 2Nd Anniversary, 2Nd Hluttaw

B AIL DENIED FOR REUTERS REPORTERS P-3 (NATIONal) NATIONAL NATIONAL L OCAL BUSINESS NATIONAL State Counsellor VP U Myint Swe wants Singapore made largest Rents rise attends Mon Myanmar to ease rules investment in Myanmar in Yangon National Day event for doing business this fiscal year townships PAGE-3 PAGe-6 PAGE-5 PAGe-6 Vol. IV, No. 291, 2nd Waning of Tabodwe 1379 ME www.globalnewlightofmyanmar.com Friday, 2 February 2018 State Counsellor stresses diversity, rule of law Daw Aung San Suu Kyi addresses 2nd Anniversary, 2nd Hluttaw A ceremony in commemora- tion of the Second Anniversa- ry of the Second Hluttaw was held yesterday in Nay Pyi Taw, where the State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi pointed out the importance of trust in the Hluttaw, which she described as an “essentail institution” for democracy. At the event held in dining hall of the Nay Pyi Taw Hluttaw compound, the State Counsellor said she had confidence that the Hluttaw representatives would enact laws for the betterment of the people. “Since we entered the Hlut- taw after the 2012 by-election, we learnt and studied the value, dif- ficulties, challenges, depth and subtleness of enacting laws. We gain invaluable lessons from this opportunity. That is why I expect all Hluttaw representatives to know the value of the Hluttaw and each representative. People are relying on the Hluttaw as an institution that will enact laws for the good of the people. “I have put much emphasis State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi addresses the ceremony in commemoration of the Second Anniversary of the Second Hluttaw. -

139Ee841191e99bf492575120

UNITED NATIONS OFFICE FOR THE COORDINATION OF HUMANITARIAN AFFAIRS Myanmar Cyclone Nargis OCHA Situation Report No. 53 28 November 2008 (Reporting period 14 – 27 November 2008) OVERVIEW & KEY DEVELOPMENTS • Cyclone Nargis hit Myanmar on 2-3 May 2008, affecting some 2.4 million people living in Ayeyarwady and Yangon Divisions. Almost 140,000 people were killed or remain missing, according to the official figures. While addressing residual or new emergency needs, including water shortage during the summer season, most of humanitarian partners are transiting to full recovery programming mode. Clusters are finalising the inputs to the “Post Nargis Recovery and Preparedness Plan” (PONREPP) which covers the long term recovery post Flashed Appeal (2009-2011). Concurrently, clusters are also finalising the Early Recovery Strategic Framework (ERSF), whose final draft has been approved on 21 November by the Tripartite Core Group (TCG), a high-level coordination entity, consisting of the Government of the Union of Myanmar, ASEAN and the United Nations. • The Periodic Review, building on the village tract Assessment (VTA) component of the Post- Nargis Joint Assessment (PoNJA), has completed data collection. The preliminary result was shown at the TCG Round Table, held on 26 November in Yangon. The data analysis and narratives are being finalised with clusters and the final draft will be submitted to the Periodic Review Strategic Advisory Group on 3 December and to the TCG on 6 December. It is planned that the results of the first Periodic Review, together with PONREPP will be shared at the UN/ASEAN summit in Thailand, planned for mid December. • Discussions continue on the ways forward for the clusters and coordination mechanisms beyond the emergency phase at the Humanitarian Country Team/IASC and among cluster leads. -

Final Report

The Union of Myanmar No. Rehabilitation and Reconstruction Sub-committee OUTLINE DESIGN STUDY REPORT ON THE PROJECT FOR CONSTRUCTION OF PRIMARY SCHOOL-CUM-CYCLONE SHELTERS IN THE AREA AFFECTED BY CYCLONE “NARGIS” IN THE UNION OF MYANMAR FINAL REPORT AUGUST 2009 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY(JICA) YACHIYO ENGINEERING CO., LTD GED JR 09-084 The Union of Myanmar Rehabilitation and Reconstruction Sub-committee OUTLINE DESIGN STUDY REPORT ON THE PROJECT FOR CONSTRUCTION OF PRIMARY SCHOOL-CUM-CYCLONE SHELTERS IN THE AREA AFFECTED BY CYCLONE “NARGIS” IN THE UNION OF MYANMAR FINAL REPORT AUGUST 2009 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) YACHIYO ENGINEERING CO., LTD PREFACE In response to a request from the Government of the Union of Myanmar, the Government of Japan decided to conduct an outline design study on the Project for Construction of Primary School -cum- Cyclone Shelters in the Area affected by Cyclone “Nargis” in the Union of Myanmar and entrusted the study to the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). JICA sent to The Union of Myanmar a study team from 21st February to 1st May 2009. The team held discussions with the officials concerned of the Government of the Union of Myanmar, and conducted a field study at the study area. After the team returned to Japan, further studies were made. Then, a mission was sent to the Union of Myanmar in order to discuss a draft outline design, and as this result, the present report was finalized. I hope that this report will contribute to the promotion of the project and to the enhancement of friendly relations between our two countries. -

Soba 4.1: Fisheries in the Ayeyarwady Basin

SOBA 4.1: FISHERIES IN THE AYEYARWADY BASIN AYEYARWADY STATE OF THE BASIN ASSESSMENT (SOBA) Status: FINAL Last Updated: 06/01/2018 Prepared by: Eric Baran, Win Ko Ko, Zi Za Wah, Khin Myat Nwe, Gurveena Ghataure, Khin Maung Soe Disclaimer "The Ayeyarwady State of the Basin Assessment (SOBA) study is conducted within the political boundary of Myanmar, where more than 93% of the Basin is situated." i NATIONAL WATER RESOURCES COMMITTEE (NWRC) | AYEYARWADY STATE OF THE BASIN ASSESSMENT (SOBA) REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 FISHERIES SYSTEMS ............................................................................................................................... 6 1.1 Ayeyarwady Fishing Systems ...................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Fishing Methods .......................................................................................................................... 8 1.3 Stocking ..................................................................................................................................... 10 2 FISHERIES STATISTICS ........................................................................................................................... 12 2.1 Tools Required for Fisheries Monitoring ................................................................................... 12 2.2 Fisheries Monitoring: Main Data Available................................................................................ 13 2.3 Reassessment of Capture Fisheries Statistics in -

Presence, Distribution, Migration Patterns and Breeding Sites of Thirty Fish Species in the Ayeyarwady System in Myanmar

PRESENCE, DISTRIBUTION, MIGRATION PATTERNS AND BREEDING SITES OF THIRTY FISH SPECIES IN THE AYEYARWADY SYSTEM IN MYANMAR WIN KO KO2, ZI ZA WAH2, Norberto ESTEPA3, OUCH Kithya1 SARAY Samadee1, KHIN MYAT NWE2, Xavier TEZZO1, Eric BARAN1 1 WorldFish 2 Myanmar Department of Fisheries, 3 Consultant TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 1 2 METHODOLOGY .............................................................................................................................. 1 2.1 Approach ................................................................................................................................. 1 2.2 Area studied ............................................................................................................................ 2 2.1 Surveys of fishermen .............................................................................................................. 3 2.1 Species selection ..................................................................................................................... 3 2.2 Data analysis ........................................................................................................................... 7 2.3 Ecological value of townships ................................................................................................. 8 2.3.1 Number of species breeding by township ............................................................................ -

Detailed Poverty and Social Impact Analysis

Resilient Community Development Project (RRP MYA 51242-002) Detailed Poverty and Social Impact Analysis October 2019 MYA: Resilient Community Development Project CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (As of 1 July 2019) Currency unit – Myanmar Kyat (MK) MK1.00 = $0.000656 $1.00 = MK1,520.00 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ADB - Asian Development Bank ART - Antiretroviral therapy CBD - community-based development CF - community facilitators DBA - Department of Border Affairs DHS - Demographic Health Survey DRD - Department of Rural Development ERLIP - Enhancing Rural Livelihoods and Incomes Project CEDAW - Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women GESIAP - Gender Equity and Social Inclusion Action Plan HHM - Household Methodologies HIV/AID - Human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immune deficiency syndrome IHLCA - Integrated Household Living Conditions Assessment KAP - Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices LIFT - Livelihood and Food Security Trust Fund MICS - Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey MOHS - Ministry of Health and Sport MOPF - Ministry of Planning and Finance MPLCS - Myanmar Poverty and Living Conditions Survey NCD - non-communicable diseases NGO - Nongovernmental organization NHP - National Health Plan NTPF - on-timber forest products NSAZ - Naga Self-Administrative Zone ORT - oral rehydration therapy PMTCT - prevention of mother to child transmission RCDP - Regional Community Development Project SDG - Sustainable Development Goal SP - subproject TB - tuberculosis TF - technical facilitators TRTA - transaction technical assistance TVET - technical and vocational education and training UNAIDS - The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS UNICEF - United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund VDP - Village Development Plan VDSC - Village Development Support Committee NOTE In this report, “$” refers to United States dollars. CONTENTS Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY I A. BACKGROUND 2 1. Methods of Poverty Assessment in Myanmar 2 2. -

1. Member List of the Study Team

1. Member List of the Study Team Name Title Organization Mr. Hidetomi OI Team Leader Japan International Cooperation Agency Mr. Shinichiro SERIZAWA Procurement Management Japan International Cooperation System Mr. Osamu HATTORI Planning Management Japan International Cooperation Agency Mr. Kohei SATO Team Leader(2nd) Japan International Cooperation Agency Mr. Jun YOSHIMIZU Deputy Team Leader(3rd) Japan International Cooperation Agency Mr. Naoyuki MINAMI Chief Consultant Yachiyo Engineering Co., Ltd. Natural Condition Survey / Mr. Tetsuo YATSU Yachiyo Engineering Co., Ltd. Social Environment Mr. Hisayuki YAMAMOTO Architectural Plan / Design 1 Yachiyo Engineering Co., Ltd. Mr. Shigeo TAKASHIMA Architectural Plan / Design 2 PACET Co., Ltd Construction and Mr. Tokio SUZUNO Procurement Plan / Yachiyo Engineering Co., Ltd. Cost Estimation Mr. Yosuke TSURUOKA Study Coordination Yachiyo Engineering Co., Ltd. 2. Schedule of Survey <First Survey> Consultant: Group A Consaltant: Group B Natural Condition Construction & Official Study Architectural Plan Architectural Plan Chief Consultant Survey / Social Procurement Plan/ No. Date Day Coordination / Design 1 / Design 2 Stay at Environment Cost Estimate Mr. Naoyuki Mr. Yosuke Mr. Hisayuki Mr. Shigeki Mr. Tetsuo Yatsu Mr, Tokio Suzuno Minami Tsuruoka Yamamoto Takashima Trip[Tokyo(11:00) TG641→Bangkok 1 1-Feb Sun (15:30) / (17:55) TG305 → Trip[Tokyo(10:55)JL717→Bangkok(16:00) / (17:55) TG305 →Yangon(18:40)] Yangon(18:40)] 2 2-Feb Mon Courtesy call and meeting at JICA, Courtesy call to EOJ ,MSWRR/MOE Yangon 3 3-Feb Tue Joint Meeting on Inception Report to the related agency (MSWEER,MOE) Yangon Courtesy call to UNDP,UNICEF,UNHCR,UN- AM/PM: Meeting with local company for survey.