Characterization of Leasable Fisheries in the Ayeyarwady Delta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yangon University of Economics Department of Commerce Master of Banking and Finance Programme

YANGON UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE MASTER OF BANKING AND FINANCE PROGRAMME INFLUENCING FACTORS ON FARM PERFORMANCE (CASE STUDY IN BOGALE TOWNSHIP, AYEYARWADY DIVISION) KHET KHET MYAT NWAY (MBF 4th BATCH – 30) DECEMBER 2018 INFLUENCING FACTORS ON FARM PERFORMANCE CASE STUDY IN BOGALE TOWNSHIP, AYEYARWADY DIVISION A thesis summited as a partial fulfillment towards the requirements for the Degree of Master of Banking and Finance (MBF) Supervised By : Submitted By: Dr. Daw Tin Tin Htwe Ma Khet Khet Myat Nway Professor MBF (4th Batch) - 30 Department of Commerce Master of Banking and Finance Yangon University of Economics Yangon University of Economics ABSTRACT This study aims to identify the influencing factors on farms’ performance in Bogale Township. This research used both primary and secondary data. The primary data were collected by interviewing with farmers from 5 groups of villages. The sample size includes 150 farmers (6% of the total farmers of each village). Survey was conducted by using structured questionnaires. Descriptive analysis and linear regression methods are used. According to the farmer survey, the household size of the respondent is from 2 to 8 members. Average numbers of farmers are 2 farmers. Duration of farming experience is from 11 to 20 years and their main source of earning is farming. Their living standard is above average level possessing own home, motorcycle and almost they owned farmland and cows. The cultivated acre is 30 acres maximum and 1 acre minimum. Average paddy yield per acre is around about 60 bushels per acre for rainy season and 100 bushels per acre for summer season. -

ANNEX 12C: PROFILE of MA SEIN CLIMATE SMART VILLAGE International Institute of Rural Reconstruction; ;

ANNEX 12C: PROFILE OF MA SEIN CLIMATE SMART VILLAGE International Institute of Rural Reconstruction; ; © 2018, INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE OF RURAL RECONSTRUCTION This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction, provided the original work is properly credited. Cette œuvre est mise à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode), qui permet l’utilisation, la distribution et la reproduction sans restriction, pourvu que le mérite de la création originale soit adéquatement reconnu. IDRC Grant/ Subvention du CRDI: 108748-001-Climate and nutrition smart villages as platforms to address food insecurity in Myanmar 33 IDRC \CRDl ..m..»...u...».._. »...m...~ c.-..ma..:«......w-.«-.n. ...«.a.u CLIMATE SMART VILLAGE PROFILE Ma Sein Village Bogale Township, Ayeyarwaddy Region 2 Climate Smart Village Profile Introduction Myanmar is the second largest country in Southeast Asia bordering Bangladesh, Thailand, China, India, and Laos. It has rich natural resources – arable land, forestry, minerals, natural gas, freshwater and marine resources, and is a leading source of gems and jade. A third of the country’s total perimeter of 1,930 km (1,200 mi) is coastline that faces the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea. The country’s population is estimated to be at 60 million. Agriculture is important to the economy of Myanmar, accounting for 36% of its economic output (UNDP 2011a), a majority of the country’s employment (ADB 2011b), and 25%–30% of exports by value (WB–WDI 2012). -

Usg Humanitarian Assistance to Burma

USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE TO BURMA RANGOON CITY AREA AFFECTED AREAS Affected Townships (as reported by the Government of Burma) American Red Cross aI SOURCE: MIMU ASEAN B Implementing NGO aD BAGO DIVISION IOM B Kyangin OCHA B (WEST) UNHCR I UNICEF DG JF Myanaung WFP E Seikgyikanaunglo WHO D UNICEF a WFP Ingapu DOD E RAKHINE b AYEYARWADY Dala STATE DIVISION UNICEF a Henzada WC AC INFORMA Lemyethna IC TI Hinthada PH O A N Rangoon R U G N O I T E G AYEYARWADY DIVISION ACF a U Zalun S A Taikkyi A D ID F MENTOR CARE a /DCHA/O D SC a Bago Yegyi Kyonpyaw Danubyu Hlegu Pathein Thabaung Maubin Twantay SC RANGOON a CWS/IDE AC CWS/IDE AC Hmawbi See Inset WC AC Htantabin Kyaunggon DIVISION Myaungmya Kyaiklat Nyaungdon Kayan Pathein Einme Rangoon SC/US JCa CWS/IDE AC Mayangone ! Pathein WC AC Î (Yangon) Thongwa Thanlyin Mawlamyinegyun Maubin Kyauktan Kangyidaunt Twantay CWS/IDE AC Myaungmya Wakema CWS/IDE Kyauktan AC PACT CIJ Myaungmya Kawhmu SC a Ngapudaw Kyaiklat Mawlamyinegyun Kungyangon UNDP/PACT C Kungyangon Mawlamyinegyun UNICEF Bogale Pyapon CARE a a Kawhmu Dedaye CWS/IDE AC Set San Pyapon Ngapudaw Labutta CWS/IDE AC UNICEF a CARE a IRC JEDa UNICEF a WC Set San AC SC a Ngapudaw Labutta Bogale KEY SC/US JCa USAID/OFDA USAID/FFP DOD Pyinkhayine Island Bogale A Agriculture and Food Security SC JC a Air Transport ACTED AC b Coordination and Information Management Labutta ACF a Pyapon B Economy and Market Systems CARE C !Thimphu ACTED a CARE Î AC a Emergency Food Assistance ADRA CWS/IDE AC CWS/IDE aIJ AC Emergency Relief Supplies Dhaka IOM a Î! CWS/IDE AC a UNICEF a D Health BURMA MERLIN PACT CJI DJ E Logistics PACT ICJ SC a Dedaye Vientiane F Nutrition Î! UNDP/PACT Rangoon SC C ! a Î ACTED AC G Protection UNDP/PACT C UNICEF a Bangkok CARE a IShelter and Settlements Î! UNICEF a WC AC J Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene WC WV GCJI AC 12/19/08 The boundaries and names used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the U.S. -

Appendix 6 Satellite Map of Proposed Project Site

APPENDIX 6 SATELLITE MAP OF PROPOSED PROJECT SITE Hakha Township, Rim pi Village Tract, Chin State Zo Zang Village A6-1 Falam Township, Webula Village Tract, Chin State Kim Mon Chaung Village A6-2 Webula Village Pa Mun Chaung Village Tedim Township, Dolluang Village Tract, Chin State Zo Zang Village Dolluang Village A6-3 Taunggyi Township, Kyauk Ni Village Tract, Shan State A6-4 Kalaw Township, Myin Ma Hti Village Tract and Baw Nin Village Tract, Shan State A6-5 Ywangan Township, Sat Chan Village Tract, Shan State A6-6 Pinlaung Township, Paw Yar Village Tract, Shan State A6-7 Symbol Water Supply Facility Well Development by the Procurement of Drilling Rig Nansang Township, Mat Mon Mun Village Tract, Shan State A6-8 Nansang Township, Hai Nar Gyi Village Tract, Shan State A6-9 Hopong Township, Nam Hkok Village Tract, Shan State A6-10 Hopong Township, Pawng Lin Village Tract, Shan State A6-11 Myaungmya Township, Moke Soe Kwin Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region A6-12 Myaungmya Township, Shan Yae Kyaw Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region A6-13 Labutta Township, Thin Gan Gyi Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region Symbol Facility Proposed Road Other Road Protection Dike Rainwater Pond (New) : 5 Facilities Rainwater Pond (Existing) : 20 Facilities A6-14 Labutta Township, Laput Pyay Lae Pyauk Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region A6-15 Symbol Facility Proposed Road Other Road Irrigation Channel Rainwater Pond (New) : 2 Facilities Rainwater Pond (Existing) Hinthada Township, Tha Si Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region A6-16 Symbol Facility Proposed Road Other Road -

Wakema Township Report

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census AYEYAWADY REGION, MYAUNGMYA DISTRICT Wakema Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population October 2017 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Ayeyawady Region, Myaungmya District Wakema Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population Office No.48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431062 www.dop.gov.mm October 2017 Figure 1 : Map of Ayeyawady Region, showing the townships Wakema Township Figures at a Glance 1 Total Population 289,106 2 Population males 140,698 (48.7%) Population females 148,408 (51.3%) Percentage of urban population 7.7% Area (Km2) 1190.2 3 Population density (per Km2) 242.9 persons Median age 27.5 years Number of wards 14 Number of village tracts 126 Number of private households 67,448 Percentage of female headed households 21.2% Mean household size 4.2 persons 4 Percentage of population by age group Children (0 – 14 years) 30.3% Economically productive (15 – 64 years) 64.1% Elderly population (65+ years) 5.5% Dependency ratios Total dependency ratio 55.9 Child dependency ratio 47.3 Old dependency ratio 8.6 Ageing index 18.3 Sex ratio (males per 100 females) 95 Literacy rate (persons aged 15 and over) 90.8% Male 93.4% Female 88.5% People with disability Number Per cent Any form of disability 23,071 8.0 Walking 9,621 3.3 Seeing 14,998 5.2 Hearing 5,924 2.0 Remembering 8,519 2.9 Type of Identity Card (persons aged 10 and over) Number Per cent Citizenship Scrutiny -

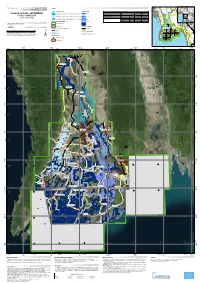

Irrawaddy Delta - MYANMAR Flooded Area Delineation 11/08/2015 11:46 UTC River R

Nepal (!Loikaw GLIDE number: N/A Activation ID: EMSR130 I Legend r n r India China e Product N.: 16IRRAWADDYDELTA, v2, English Magway a Rakhine w Bangladesh e a w l d a Vietnam Crisis Information Hydrology Consequences within the AOI on 09, 10, 11/08/2015 d Myanmar S Affected Total in AOI y Nay Pyi Taw Irrawaddy Delta - MYANMAR Flooded Area delineation 11/08/2015 11:46 UTC River R ha 428922,1 i v Laos Flooded area e ^ r S Flood - 01/08/2015 Flooded Area delineation 10/08/2015 23:49 UTC Stream Estimated population Inhabitants 4252141 11935674 it Bay of ( to Settlements Built-up area ha 35491,8 75542,0 A 10 Bago n Bengal Thailand y g Delineation Map e Flooded Area delineation 09/08/2015 11:13 UTC Lake y P Transportation Railways km 26,0 567,6 a Cambodia r i w Primary roads km 33,0 402,1 Andam an n a Gulf of General Information d Sea g Reservoir Secondary roads km 57,2 1702,3 Thailand 09 y Area of Interest ) Andam an Cartographic Information River Sea Missing data Transportation Bay of Bengal 08 Bago Tak Full color ISO A1, low resolution (100 dpi) 07 1:600000 Ayeyarwady Yangon (! Administrative boundaries Railway Kayin 0 12,5 25 50 Region km Primary Road Pathein 06 04 11 12 (! Province Mawlamyine Grid: WGS 1984 UTM Zone 46N map coordinate system Secondary Road 13 (! Tick marks: WGS 84 geographical coordinate system ± Settlements 03 02 01 ! Populated Place 14 15 Built-Up Area Gulf of Martaban Andaman Sea 650000 700000 750000 800000 850000 900000 950000 94°10'0"E 94°35'0"E 95°0'0"E 95°25'0"E 95°50'0"E 96°15'0"E 96°40'0"E 97°5'0"E N " 0 ' 5 -

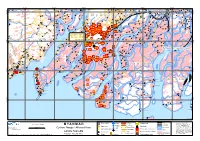

Tropical Cyclone Nargis

Minbu Myanmar: Tropical CycloneTaungdwingyi Nargis (as of 7 May 2008) • Population in disaster-declared Government authorized UN GMT +6:30 to airlift relief items from the areas: approx. 24 million United Nations Humanitarian • In Yangon: approx. 6 million Response Depot (UNHRD) in CHINA • Over 1 million expected to be Brindisi, Italy. INDIA SITUATION in need of urgent humanitarian assistance MYANMAR • Cyclone Nargis struck Myanmar • 22,000 dead 4 May LAO on 2 and 3 May 2008, sweeping • 41,000 missing P.D.R. through the Ayeyarwady • 90-95% of the buildings in 7 Toungoo 3 May 2 May (Irrawaddy) Delta region and townships destroyed 1 May THAILAND SOUTH the country’s largest city, 30 Apr CHINA Yangon. WFP food commodities MYANMAR CAMBODIA SEA • Total: 3,800 MT • Severe flooding, damaged Pyu 27 Apr • In Yangon: 980 MT infrastructure and ANDAMAN Gulf of communications pose major SEA Thailand Myanaung I logistical problems both for r a Bago w assessment and for provision of a d d relief. y Nyaunglebin • Relief capacity inside the country already severely Bay of stretched, both in terms of supplies and human resources. Bengal Henzada • Severe food security situation. Thanatpin Kyaikto LINKS Ayeyawaddy Yangon Kayin • Affected by severe Yandoon Thaton floods • OCHA Situation Report No. 4 80 MT of rice delivery Hlaingtharya • >1,000 homeless • Latest updates for Myanmar: Syriam • 100 homes inundated Tropical Cyclone Nargis planned for today, split • 10,000 dead Kayan Tak between Hlaingtharya • 190,000 homeless Twante • Related maps and Labutta Yangon Thongwa Wakema Martaban Kyaiklat Disclaimers: Moulmeingyun The boundaries and names shown and the 30 MT of rice Mudon designations used on all maps do not imply Labutta Bogale Pyapon delivered to clinics official endorsement or acceptance by the THAILAND United Nations. -

B O G a L E Mawlamyinegyun Wakema Labutta M Y a U N G M Y a N

94°20’0"E 94°30’0"E 94°40’0"E 94°50’0"E 95°0’0"E 95°10’0"E CHAUNGAUK KYETTHUNGYAUNG DAYIN-GAUK PEINNEGYAUNG YEGYAN KONGALE TUMYAUNG ONBINZEIKPONSOGYI BYAINGDAUNG YWATHIT NYAUNGLAN UDOCHAUNG MEZALI-UDO YEGYAWGYI KYAUKKWE KYAGWIN HM ANGU KWINBAT KYAUKPON POBYE KANGYAUNG THONGWA KYAWNU-UDO HGETKYIDAN SHWEKA YWATHITGALE NGAYOKTHI THAYETKON LABUTPYE SHWEZAN THEGYAUNG SEIKKYI YWATHITGALE KYAUKPYAGALE PAWDAW MU YWATHIT MEZALI MANKALA THAYETCHAUNG LEGWA TIKOGAING KYAUKKWE BEBAUK KYONLATA KYUNTHIT WakemaNYAUNGGYAUNG KANGON LE-EINDAN KALAMATAUNG TA U KS H A PACHAUNG KYEINNI SABYUZU SHANZU THALIGAGON HM ANGU SABYUZU TALAPHIKYUN HTANNYETCHAUNG ALEGYAUNG AUNGHLAING 16°20’0"N KINMONZEIK NONKYUN-AUKSU 16°20’0"N MAUNG-BI KYEINGONGYI THAYEGYAUNG BUDINGYAUNG ZAYATCHAUNGBYA PEIKTA DUNWAING PEINGYAUNG YAKAINGGON THINGANBYU YAMALNW KYONLATA-AWA MYINDALIN LEIKABO KYIGYAUNG POLAUNG KOKKO KANGYAUNG KUNGWIN THAINGGYAUNG MyaungmyaLEBYAUK KYONLAMU MYATTHA-UDO POYANGON KANAZOGYAUNG NYAUNGBINTHA KWINGYAUNG MINGON MYITKYO SETKON NGADA NTAY TEBIN MOGAUNG MAYANGON EINMAGON KYUDAW THAUNGBON KYONLATA BYAUNGBYAN PO-SHWE HLAW MEZALI THEGYAUNG MYAHPUGYAUNG PYINMAGYAUNG-WA KHAYEGON KYAGAN KYAGAN PYAKEIK SE-EINZU KYAGYAUNG NGAYANGAUNGDO KYUNGALE MWEHAUK THEGON SAMALAUK CHAUNGBYA MABE POTILUT CHAUNGBYA KATHABAUNG AWABEIK CHAUNGGWEGYI AUNGHLAING NAT-HMU KYUTKON CHAUNGGWE KYAUKGYI ALEYWA THINDAWGYI PEIKTAGYI SHAUKCHAUNG YWATHIT MAYANGON KYAUKPYAKWIN BAWINSU KYAUKPYA LEIKPOK KYUNGYAUNG THAHTEGON THAMA AH-KA YWATHIT YEGYOGON HLAINGBON SANGYIGON THAYETPINGWIN KABALU NY EINU DIPAYON -

Union of Myanmar Ministry of Health and Sports

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR MINISTRY OF HEALTH AND SPORTS 46TH MYANMAR HEALTH RESEARCH CONGRESS Programme and Abstracts 8-12 January 2018 The Republic of the Union of Myanmar Ministry of Health and Sports 46th MYANMAR HEALTH RESEARCH CONGRESS Programme and Abstracts 8-12 January 2018 FOREWORD The 46th Myanmar Health Research Congress, organized by the Ministry of Health and Sports will be held at the Department of Medical Research with the aims of attaining the highest quality in health care by promoting research capacity strengthening of healthcare personnel and providing evidence‐based, applicable research findings to end‐users by researchers. In today’s world, we are facing the growing burden of Non‐Communicable Diseases including cancer therefore this year’s congress theme is most appropriate and timely being “To Prevent, Detect, Treat & Live with Cancer”. As we strive for Universal Health Coverage, we look forward to a healthier Myanmar where cancer is detected at early stage and all cancer patients receive quality health care and quality of life. For this to become a reality, research plays a pivotal role for making the correct decisions in cancer diagnosis and subsequent management. All researchers under the Ministry of Health and Sports felt a surge of pride as our National Health Research Policy was approved by the cabinet in September 2017. Among many important issues, to promote Ethical and Responsible Conduct of Research, to develop a national health research agenda and to establish a national health information system for avoiding duplication and redundancy as well as for promoting effective dissemination and appropriate utilization of research findings were included. -

Myanmar Transport Brief ANALYSIS Issue 17 DATA TENDERS 30 March 2017 COMPANIES

NEWS Myanmar Transport Brief ANALYSIS DATA Issue 17 TENDERS 30 March 2017 COMPANIES Part of the Myanmar Transport Monitor transport.frontiermyanmar.com IN THIS ISSUE Ministry backs off corporatisation plan for Inland Water Transport Plans to transform state-owned IWT into a corporation abandoned as Ministry cites hardships that would be caused for government staff. Shan State submits proposal for international flights from Heho Proposal to connect Heho, near Inle Lake, with Chinese and Thai cities likely to be opposed by domestic airlines TRANSPORT NUMBER OF Q&A: EFR group chairman U Kyaw Lwin Oo THE WEEK Myanmar Transport Monitor met with EFR group chairman U Kyaw Lin Oo to discuss challenges and opportunities facing logistics companies in Myanmar. 684,568 passengers Minister claims Thilawa-Bago highway construction to begin next year About 684,568 passengers Declining demand strains Naypyitaw highway bus companies used the Yangon- Ministry of Construction removes Yangon bridge tolls on 1 April Naypyitaw route via bus in Daw Aung San Suu Kyi remarks on weakness of Sagaing transportation 2016, 70,000 fewer than in 2015 and about 115,000 Authorities to end private road toll collection in Tanintharyi Region less than in 2013, the year Buthidaung-Yathedaung bridge in Rakhine State opened of the SEA Games in Authorities announce Yangon water taxis will launch in May Naypyitaw. Upgrade works at six Yangon Circular Railway stations almost complete Improved trains coming for Mandalay-Myitkyina route The route was formerly an essential service after the Authorities plan crackdown on van owners illegally ferrying passenger capital was moved from Two firms shortlisted for Yangon bus passenger information system Yangon to Naypyitaw in Japan hands over first of three vessels for Rakhine State 2005. -

Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar

Myanmar Development Research (MDR) (Present) Enlightened Myanmar Research (EMR) Wing (3), Room (A-305) Thitsar Garden Housing. 3 Street , 8 Quarter. South Okkalarpa Township. Yangon, Myanmar +951 562439 Acknowledgement of Myanmar Development Research This edition of the “Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010-2012)” is the first published collection of facts and information of political parties which legally registered at the Union Election Commission since the pre-election period of Myanmar’s milestone 2010 election and the post-election period of the 2012 by-elections. This publication is also an important milestone for Myanmar Development Research (MDR) as it is the organization’s first project that was conducted directly in response to the needs of civil society and different stakeholders who have been putting efforts in the process of the political transition of Myanmar towards a peaceful and developed democratic society. We would like to thank our supporters who made this project possible and those who worked hard from the beginning to the end of publication and launching ceremony. In particular: (1) Heinrich B�ll Stiftung (Southeast Asia) for their support of the project and for providing funding to publish “Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010-2012)”. (2) Party leaders, the elected MPs, record keepers of the 56 parties in this book who lent their valuable time to contribute to the project, given the limited time frame and other challenges such as technical and communication problems. (3) The Chairperson of the Union Election Commission and all the members of the Commission for their advice and contributions. -

Annex 8 Myanmar

Sustainable Management of Peatland Forests in Southeast Asia SEApeat Project - Myanmar Component Progressive Report for First Quarter 2014 Description of Project in brief Component/Country : The Republic of Union of Myanmar Project Period : One years (2014) Project Budget : USD 49,000 Funding Agency : European Union (EU) through Global Environment Centre (GEC ) Regional Implementing : Global Environmental Centre Agency (GEC) Focal Point : Environmental Conservation Department (ECD) Implementing Partner : FREDA in cooperation with ECD and FD (MOECAF), AD and SLRD (MAI) Activities to be implemented in 2014 1. Technical Workshop on Sustainable Peatland Management 2. Replicated trainings and Peat Assessment 3. Pilot-testing – for best management practices of peatland 4. Awareness and Education Campaign Achievement so far: (1) Technical Workshop on Sustainable Peatland Management (2) Coordination meetings (3) Trainings and awareness campaign (4) Peat Assessment (i) Ayeyarwady Region (ii) Shan State (iii) Thanintharyi Region Technical Workshop on Sustainable Peatland Management Venue : Tungapuri Hotel, Yarza Thingaha Rd, Nay Pyi Taw Date : 30th January, 2014 Attendees : (61) persons who are the most responsible and interested staff of Ministry of Environmental Conservation and Forestry, Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation, University of Agriculture, University of Forestry, NGOs, Global Environmental Centre (GEC) and FREDA Deputy Ministers, Dr. Daw Thet Thet Zin and U Aye Myint Maung attended the Workshop and Dr. Daw Thet Thet Zin delivered the opening speech. Deputy Ministers of MOECAF viewing the display at Technical Workshop Technical Workshop being in session Workshop Presentations 1. Sustainable Peatland Management in South East Asia by GEC 2. SEApeat Project (Myanmar Component) by ECD (MOECAF) 3. Some facts about Peat Soil and Peatland by FREDA 4.