Black US Army Bands and Their Bandmasters in World War I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8364 Licensed Charities As of 3/10/2020 MICS 24404 MICS 52720 T

8364 Licensed Charities as of 3/10/2020 MICS 24404 MICS 52720 T. Rowe Price Program for Charitable Giving, Inc. The David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust USA, Inc. 100 E. Pratt St 25283 Cabot Road, Ste. 101 Baltimore MD 21202 Laguna Hills CA 92653 Phone: (410)345-3457 Phone: (949)305-3785 Expiration Date: 10/31/2020 Expiration Date: 10/31/2020 MICS 52752 MICS 60851 1 For 2 Education Foundation 1 Michigan for the Global Majority 4337 E. Grand River, Ste. 198 1920 Scotten St. Howell MI 48843 Detroit MI 48209 Phone: (425)299-4484 Phone: (313)338-9397 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 46501 MICS 60769 1 Voice Can Help 10 Thousand Windows, Inc. 3290 Palm Aire Drive 348 N Canyons Pkwy Rochester Hills MI 48309 Livermore CA 94551 Phone: (248)703-3088 Phone: (571)263-2035 Expiration Date: 07/31/2021 Expiration Date: 03/31/2020 MICS 56240 MICS 10978 10/40 Connections, Inc. 100 Black Men of Greater Detroit, Inc 2120 Northgate Park Lane Suite 400 Attn: Donald Ferguson Chattanooga TN 37415 1432 Oakmont Ct. Phone: (423)468-4871 Lake Orion MI 48362 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Phone: (313)874-4811 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 25388 MICS 43928 100 Club of Saginaw County 100 Women Strong, Inc. 5195 Hampton Place 2807 S. State Street Saginaw MI 48604 Saint Joseph MI 49085 Phone: (989)790-3900 Phone: (888)982-1400 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 58897 MICS 60079 1888 Message Study Committee, Inc. -

Black US Army Bands and Their Bandmasters in World War I

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications: School of Music Music, School of Fall 8-21-2012 Black US Army Bands and Their Bandmasters in World War I Peter M. Lefferts University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpub Part of the Music Commons Lefferts, Peter M., "Black US Army Bands and Their Bandmasters in World War I" (2012). Faculty Publications: School of Music. 25. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpub/25 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications: School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 1 Version of 08/21/2012 This essay is a work in progress. It was uploaded for the first time in August 2012, and the present document is the first version. The author welcomes comments, additions, and corrections ([email protected]). Black US Army bands and their bandmasters in World War I Peter M. Lefferts This essay sketches the story of the bands and bandmasters of the twenty seven new black army regiments which served in the U.S. Army in World War I. They underwent rapid mobilization and demobilization over 1917-1919, and were for the most part unconnected by personnel or traditions to the long-established bands of the four black regular U.S. Army regiments that preceded them and continued to serve after them. Pressed to find sufficient numbers of willing and able black band leaders, the army turned to schools and the entertainment industry for the necessary talent. -

America Enters WWI on April 6, 1917 WW I Soldiers and Sailors

America enters WWI on April 6, 1917 WW I Soldiers and Sailors associated with Morris County, New Jersey By no means is this is a complete list of men and women from the Morris County area who served in World War I. It is a list of those known to date. If there are errors or omissions, we request that additions or corrections be sent to Jan Williams [email protected] This list provides names of people listed as enlisting in Morris County, some with no other connection known to the county at this time. This also list provides men and women buried in Morris County, some with no other connection known to the County at this time. Primary research was executed by Jan Williams, Cultural & Historic Resources Specialist for the Morris County Dept. of Planning & Public Works. THE LIST IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER WW I Soldiers and Sailors associated with Morris County, New Jersey Percy Joseph Alvarez Born February 23, 1896 in Jacksonville, Florida. United States Navy, enlisted at New York (date unknown.) Served as an Ensign aboard the U.S.S. Lenape ID-2700. Died February 5, 1939, buried Locust Hill Cemetery, Dover, Morris County, New Jersey. John Joseph Ambrose Born Morristown June 20, 1892. Last known residence Morristown; employed as a Chauffer. Enlisted July 1917 aged 25. Attached to the 4 MEC AS. Died February 27, 1951, buried Gate of Heaven Cemetery, East Hanover, New Jersey. Benjamin Harrison Anderson Born Washington Township, Morris County, February 17, 1889. Last known residence Netcong. Corporal 310th Infantry, 78th Division. -

·Osler·L Brary·Newsl Tter·

The ·Osler·L ibrary·Newsle tter· Number 121 · Fall 2014 O Osler Library of the History of Medicine, McGill University, MontréalNUMBER (Québec) 111 Canada · 2009 Osler Library Research Travel Grant receives an endowment in honour of Dr. Edward Horton Bensley (1906-1995) The Osler Library is very pleased to announce that it has received a $100,000 gift from the Pope-Jackson Fund to endow the Osler Library Research Travel Grant. In making the gift, the fund wanted to facilitate access to the library’s collection for scholars living beyond Montreal, and, when possible, for scholars living outside Canada. The fund also wished to recognize Dr. E.H. Bensley’s place in the history of the library. The travel grant has been renamed the Dr. Edward H. Bensley Osler Library Research Travel Grant. It is fitting that someone who loved medical history and the library so much would be memorialized in this way. Dr. Edward Bensley played IN THIS ISSUE a special role in the Osler Library. As Dr. Brais 3 - Osler Library acquires two rare incunables notes below, he joined the 4 - Aristotle’s Masterpiece: Department of the History Report of the 2014 Osler of Medicine (fore-runner of Library Research Travel the present Department of Grant Winner Social Studies of Medicine) 6 - A World War One and taught the history of Remembrance: Finding Revere and medicine to second year McGill’s First World War medical students, edited Hospital the Osler Library Newsletter 8 - Annual Appeal and wrote extensively. His 12 - ‘Cardiac Greetings’ last book, “McGill Medical from down under Luminaries,” was the first 14 - A shared history of title to appear in the Osler Dr. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

Coal Crisis Returns Dimout to Chicago

eas Report® ® USAFE WEATHER FORECAST One Year Ago Today NORTH & WEST: Partly cloudy, Max. Nazis quit by thousands; Baltic 75, Min. 46; SOUTH & EAST Clear to partly cloudy, Max 80. Min. 46; collapse expected. Americans and BERLIN, same as N & W. Max. 70, THE STIRS A Min. 44; VIENNA: Same as S & E. British meet Russians. Allies begin BREMEN: Same as N & W, Max. 72, roundup of Italy foe. Min. 44. Unom«i*l Newspaper of US. Armed Volume 2, Number 122 20 Pfg., 2 fr„ 1 d. Friday, May 3, 1946 Book Gives Put ton Credit For St. Lo Breakthrough Coal Crisis Returns NEW YORK, May 2 (UP) — Gen. it and used not only 1st Army George S. Patton, even though dead, troops but also a number of his own was right back today where he al- 3rd Army units." Wallace does give ways liked to be—in the middle of a Bradley credit for his foresight in hot argument. placing Patton in command of the Dimout to Chicago Col. Benton G. Wallace, a staff! breakthrough itself. officer under "Old Blood and Guts," With his 3rd Army dander really has written a book which is sure to up, the colonel also charges that burn the Army's brass. It is called rolling Thirders — presumably after "Patton and the Third Army." they captured Argentan — were Wallace says that Patton was New York Seen ordered to stop dead in their tracks chiefly responsible both for the pfen- and were not allowed to close the Adriatic Isles Given ning and for the execution of the bloody Falaise gap, a maneuver famous St. -

Download (9MB)

Beiträge zur Hydrologie der Schweiz Nr. 39 Herausgegeben von der Schweizerischen Gesellschaft für Hydrologie und Limnologie (SGHL) und der Schweizerischen Hydrologischen Kommission (CHy) Daniel Viviroli und Rolf Weingartner Prozessbasierte Hochwasserabschätzung für mesoskalige Einzugsgebiete Grundlagen und Interpretationshilfe zum Verfahren PREVAH-regHQ | downloaded: 23.9.2021 Bern, Juni 2012 https://doi.org/10.48350/39262 source: Hintergrund Dieser Bericht fasst die Ergebnisse des Projektes „Ein prozessorientiertes Modellsystem zur Ermitt- lung seltener Hochwasserabflüsse für beliebige Einzugsgebiete der Schweiz – Grundlagenbereit- stellung für die Hochwasserabschätzung“ zusammen, welches im Auftrag des Bundesamtes für Um- welt (BAFU) am Geographischen Institut der Universität Bern (GIUB) ausgearbeitet wurde. Das Pro- jekt wurde auf Seiten des BAFU von Prof. Dr. Manfred Spreafico und Dr. Dominique Bérod begleitet. Für die Bereitstellung umfangreicher Messdaten danken wir dem BAFU, den zuständigen Ämtern der Kantone sowie dem Bundesamt für Meteorologie und Klimatologie (MeteoSchweiz). Daten Die im Bericht beschriebenen Daten und Resultate können unter der folgenden Adresse bezogen werden: http://www.hydrologie.unibe.ch/projekte/PREVAHregHQ.html. Weitere Informationen erhält man bei [email protected]. Druck Publikation Digital AG Bezug des Bandes Hydrologische Kommission (CHy) der Akademie der Naturwissenschaften Schweiz (scnat) c/o Geographisches Institut der Universität Bern Hallerstrasse 12, 3012 Bern http://chy.scnatweb.ch Zitiervorschlag -

North Lancashire Regiment

H' UCiiB LIBRARY THE WAR HISTORY OF THE IST/4TH BATTALION THE LOYAL NORTH LANCASHIRE REGIMENT THE COLOURS THE WAR HISTORY iJl- Tllli ist/4th Battalion The Loyal North Lancashire Regiment, uoiv The Loyal Regiment (North hancashire). I 9 I 4- I 9 I S " The Lancashire ftwl were as itotil men «5 were in Ihc wr/d and as brave firemen. I have often told them they were as good fighters and as great plunderers as ever ucnt to a field .... " It was to admiration tn see what a sfjirit of courage and resolution there was amongst us, and how God hid us from the fsars and dangers we were exposed to." CaPTAI.N HoDCSO.V, writing I.N' 1648, ON THE I3ATTLE OF TrESTON. [copyright] mil Prinlcd Ijy Geo. Toii.MIN & Sons, Ltd.. ( 'uardiaii Work-., rrL-ston. Published l)v the liATTALluN lllsroRV CoMMIIlKK. Photo : .1. IVinter, I'tiston, LIEUTENANT-COLONEL RALPH HINDLE, D S 0. He commanded the Battalion from I'cbruary, 1915, till wounded in action at Fcstubert, and afjain from August, 1915, till killed in action at Vaucellette l-"arm, on 30th November, 1917. " What do these fellows mean by saying, ' I've done »iy bit' ? What is titeir ' bit' ? I don't consider I've done mine yf/."—Lieutenant-Colonel Hindlc in 1917. l^ebicatioiL Co Cfje JftDaiii 2^obp of our Comrabeg, U3t)o ijabe gone fortoarb in tnuuiplj to tfje ilnknolun Haitb, Clje aear Partp, left befjinb to clean up anb Ijanb ober, ©ebicate tfjis^ book. PREFACE The purpose of this book is to supply to the people of Preston and district, for the first time, a complete and authentic record of the adventures -

The Military Lending Act Five Years Later

The Military Lending Act Five Years Later Impact On Servicemembers, the High-Cost Small Dollar Loan Market, and the Campaign against Predatory Lending Jean Ann Fox Director of Financial Services Consumer Federation of America May 29, 2012 1 Table of Contents Introduction ………………………………………………………………………3 I. Creditors and Consumer Credit Covered by MLA Rules…………………...5 II. Executive Summary: Findings and Recommendations…………………….9 III. Servicemembers Still Need Protection from Abusive Credit Products………………………………………………………………………14 IV. History of the Military Lending Act and DoD Regulations………………18 V. Impact of MLA on Covered Consumer Credit……………………………..21 VI. Maps Illustrate Impact of Military Lending Act at Selected Bases……...31 VII. Bank Payday Loans Not Covered by MLA Rules………………………..49 VIII. No Impact on Military Installment Loans……………………………….61 IX. No Impact on State Regulation of Lending to Non-resident Borrowers…………………………………………………………………….73 X. No Impact on Retail Installment Sales Credit or Rent-to-Own…………...76 XI. Enforcement Tools for Military Lending Act Must be Strengthened……81 XII. No Impact of Military Lending Act Allotment Protections……………...94 XIII. Impact of MLA on Advocacy to Protect all Americans……………….102 XIV. Access to Relief Society Assistance and Better Financial Options……104 2 The Military Lending Act Five Years Later Impact On Servicemembers, the High-Cost Small Dollar Loan Market, and the Campaign against Predatory Lending by Jean Ann Fox Consumer Federation of America May 29, 2012 Five years ago the Department of Defense -

The Influence of Louis Armstrong on the Harlem Renaissance 1923-1930

ABSTRACT HUMANITIES DECUIR, MICHAEL B.A. SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY AT NEW ORLEANS, 1987 M.A. THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY, 1989 THE INFLUENCE OF LOUIS ARMSTRONG ON THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE 1923–1930 Committee Chair: Timothy Askew, Ph.D. Dissertation dated August 2018 This research explores Louis Armstrong’s artistic choices and their impact directly and indirectly on the African-American literary, visual and performing arts between 1923 and 1930 during the period known as the Harlem Renaissance. This research uses analyses of musical transcriptions and examples of the period’s literary and visual arts to verify the significance of Armstrong’s influence(s). This research also analyzes the early nineteenth century West-African musical practices evident in Congo Square that were present in the traditional jazz and cultural behaviors that Armstrong heard and experienced growing up in New Orleans. Additionally, through a discourse analysis approach, this research examines the impact of Armstrong’s art on the philosophical debate regarding the purpose of the period’s art. Specifically, W.E.B. Du i Bois’s desire for the period’s art to be used as propaganda and Alain Locke’s admonitions that period African-American artists not produce works with the plight of blacks in America as the sole theme. ii THE INFLUENCE OF LOUIS ARMSTRONG ON THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE 1923–1930 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF CLARK ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF ARTS IN HUMANITIES BY MICHAEL DECUIR DEPARTMENT OF HUMANITIES ATLANTA, GEORGIA AUGUST 2018 © 2018 MICHAEL DECUIR All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My greatest debt of gratitude goes to my first music teacher, my mother Laura. -

Welsh Guards Magazine 2011

WREGEIMLENSTAHL MGAGUAZAINRE 2D01S 1 WELSH GUARDS REGIMENTAL MAGAZINE 2011 COLONEL-IN-CHIEF Her Majesty The Queen COLONEL OF THE REGIMENT His Royal Highness The Prince of Wales KG KT GCB OM AK QSO PC ADC REGIMENTAL LIEUTENANT COLONEL Brigadier R H Talbot Rice REGIMENTAL ADJUTANT Colonel (Retd) T C S Bonas BA ASSISTANT REGIMENTAL ADJUTANT Major (Retd) K F Oultram * REGIMENTAL HEADQUARTERS Wellington Barracks, Birdcage Walk, London, SW1E 6HQ Contact Regimental Headquarters by Email: [email protected] View the Regimental Website at www.army.mod.uk/welshguards * AFFILIATIONS 5th/7th Battalion The Royal Australian Regiment HMS Campbeltown 1 WELSH GUARDS REGIMENTAL MAGAZINE CONTENTS FOREWORD WELSH GUARDS AFGHANISTAN APPEAL ADVERTISEMENTS ................................................ 95 Regimental Lieutenant Colonel ......................... 3 The Welsh Guards Afghanistan Appeal By The Commanding Officer WELSH GUARDS COLLECTION ................ 100 by Col Bonas ................................................................ 53 1st Bn Welsh Guards ................................................. 4 Charity Golf Day ......................................................... 57 WELSH GUARDS ASSOCIATION 1ST BATTALION WELSH GUARDS Ride of Respect ........................................................... 60 ASSOCIATION BRANCH REPORTS The Prince of Wales’s Company ........................ 5 Cardiff Branch .......................................................... 102 Number Two Company ........................................... 8 BATTLEFIELD -

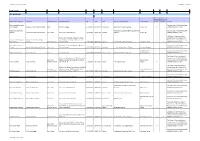

ROYAL GALLERY FIRST WORLD WAR Name (As On

Houses of Parliament War Memorials Royal Gallery, First World War ROYAL GALLERY FIRST WORLD WAR Also in Also in Westmins Commons Name (as on memorial) Full Name MP/Peer/Son of... Constituency/Title Birth Death Rank Regiment/Squadron/Ship Place of Death ter Hall Chamber Sources Shelley Leopold Laurence House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Baron Abinger Shelley Leopold Laurence Scarlett Peer 5th Baron Abinger 01/04/1872 23/05/1917 Commander Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve London, UK X MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Humphrey James Arden 5th Battalion, London Regiment (London Rifle House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Adderley Humphrey James Arden Adderley Son of Peer 3rd son of 2nd Baron Norton 16/10/1882 17/06/1917 Rifleman Brigade) Lincoln, UK MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) The House of Commons Book of Bodmin 1906, St Austell 1908-1915 / Eldest Remembrance 1914-1918 (1931); Thomas Charles Reginald Thomas Charles Reginald Agar- son of Thomas Charles Agar-Robartes, 6th House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Agar-Robartes Robartes MP / Son of Peer Viscount Clifden 22/05/1880 30/09/1915 Captain 1st Battalion, Coldstream Guards Lapugnoy, France X X MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Horace Michael Hynman Only son of 1st Viscount Allenby of Meggido House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Allenby Horace Michael Hynman Allenby Son of Peer and of Felixstowe 11/01/1898 29/07/1917 Lieutenant 'T' Battery, Royal Horse Artillery Oosthoek, Belgium MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Aeroplane over House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Francis Earl Annesley Francis Annesley Peer 6th Earl Annesley 25/02/1884 05/11/1914