Master Layout Sheet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

·Osler·L Brary·Newsl Tter·

The ·Osler·L ibrary·Newsle tter· Number 121 · Fall 2014 O Osler Library of the History of Medicine, McGill University, MontréalNUMBER (Québec) 111 Canada · 2009 Osler Library Research Travel Grant receives an endowment in honour of Dr. Edward Horton Bensley (1906-1995) The Osler Library is very pleased to announce that it has received a $100,000 gift from the Pope-Jackson Fund to endow the Osler Library Research Travel Grant. In making the gift, the fund wanted to facilitate access to the library’s collection for scholars living beyond Montreal, and, when possible, for scholars living outside Canada. The fund also wished to recognize Dr. E.H. Bensley’s place in the history of the library. The travel grant has been renamed the Dr. Edward H. Bensley Osler Library Research Travel Grant. It is fitting that someone who loved medical history and the library so much would be memorialized in this way. Dr. Edward Bensley played IN THIS ISSUE a special role in the Osler Library. As Dr. Brais 3 - Osler Library acquires two rare incunables notes below, he joined the 4 - Aristotle’s Masterpiece: Department of the History Report of the 2014 Osler of Medicine (fore-runner of Library Research Travel the present Department of Grant Winner Social Studies of Medicine) 6 - A World War One and taught the history of Remembrance: Finding Revere and medicine to second year McGill’s First World War medical students, edited Hospital the Osler Library Newsletter 8 - Annual Appeal and wrote extensively. His 12 - ‘Cardiac Greetings’ last book, “McGill Medical from down under Luminaries,” was the first 14 - A shared history of title to appear in the Osler Dr. -

Black US Army Bands and Their Bandmasters in World War I

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications: School of Music Music, School of 3-2-2018 Black US Army Bands and Their aB ndmasters in World War I Peter M. Lefferts University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpub Part of the African American Studies Commons, Military History Commons, Music Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Lefferts, Peter M., "Black US Army Bands and Their aB ndmasters in World War I" (2018). Faculty Publications: School of Music. 67. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpub/67 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications: School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 1 Version of 04/02/2018 This is the third version, put on-line in 2018, of this work-in-progress. This essay was put on-line for the first time in 2012, at (https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpuB/25/), and a second version was put on-line in 2016, at (https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpuB/55/). The author is grateful to those who have contacted him aBout this work and welcomes further comments, additions, and corrections ([email protected]). Black US Army Bands and Their Bandmasters in World War I Peter M. Lefferts This essay sketches the story of the Bands and Bandmasters of the twenty seven new black army regiments which served in the U.S. -

North Lancashire Regiment

H' UCiiB LIBRARY THE WAR HISTORY OF THE IST/4TH BATTALION THE LOYAL NORTH LANCASHIRE REGIMENT THE COLOURS THE WAR HISTORY iJl- Tllli ist/4th Battalion The Loyal North Lancashire Regiment, uoiv The Loyal Regiment (North hancashire). I 9 I 4- I 9 I S " The Lancashire ftwl were as itotil men «5 were in Ihc wr/d and as brave firemen. I have often told them they were as good fighters and as great plunderers as ever ucnt to a field .... " It was to admiration tn see what a sfjirit of courage and resolution there was amongst us, and how God hid us from the fsars and dangers we were exposed to." CaPTAI.N HoDCSO.V, writing I.N' 1648, ON THE I3ATTLE OF TrESTON. [copyright] mil Prinlcd Ijy Geo. Toii.MIN & Sons, Ltd.. ( 'uardiaii Work-., rrL-ston. Published l)v the liATTALluN lllsroRV CoMMIIlKK. Photo : .1. IVinter, I'tiston, LIEUTENANT-COLONEL RALPH HINDLE, D S 0. He commanded the Battalion from I'cbruary, 1915, till wounded in action at Fcstubert, and afjain from August, 1915, till killed in action at Vaucellette l-"arm, on 30th November, 1917. " What do these fellows mean by saying, ' I've done »iy bit' ? What is titeir ' bit' ? I don't consider I've done mine yf/."—Lieutenant-Colonel Hindlc in 1917. l^ebicatioiL Co Cfje JftDaiii 2^obp of our Comrabeg, U3t)o ijabe gone fortoarb in tnuuiplj to tfje ilnknolun Haitb, Clje aear Partp, left befjinb to clean up anb Ijanb ober, ©ebicate tfjis^ book. PREFACE The purpose of this book is to supply to the people of Preston and district, for the first time, a complete and authentic record of the adventures -

Invention of Hysteria : Charcot and the Photographic Iconography of the Salpêtrière / Georges Didi-Huberman ; Translated by Alisa Hartz

Invention of Hysteria This page intentionally left blank Invention of Hysteria Charcot and the Photographic Iconography of the Salpêtrière Georges Didi-Huberman Translated by Alisa Hartz The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England Originally published in 1982 by Éditions Macula, Paris. ©1982 Éditions Macula, Paris. This translation ©2003 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or infor- mation storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. This book was set in Bembo by Graphic Composition, Inc. Printed and bound in the United States of America. Cet ouvrage, publié dans le cadre d’un programme d’aide à la publication, béné- ficie du soutien du Ministère des Affaires étrangères et du Service Culturel de l’Ambassade de France aux Etats-Unis. This work, published as part of a program of aid for publication, received sup- port from the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Cultural Services of the French Embassy in the United States. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Didi-Huberman, Georges. [Invention de l’hysterie, English] Invention of hysteria : Charcot and the photographic iconography of the Salpêtrière / Georges Didi-Huberman ; translated by Alisa Hartz. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-262-04215-0 (hc. : alk. paper) 1. Salpêtrière (Hospital). 2. Hysteria—History. 3. Mental illness—Pictorial works. 4. Facial expression—History. -

The Military Lending Act Five Years Later

The Military Lending Act Five Years Later Impact On Servicemembers, the High-Cost Small Dollar Loan Market, and the Campaign against Predatory Lending Jean Ann Fox Director of Financial Services Consumer Federation of America May 29, 2012 1 Table of Contents Introduction ………………………………………………………………………3 I. Creditors and Consumer Credit Covered by MLA Rules…………………...5 II. Executive Summary: Findings and Recommendations…………………….9 III. Servicemembers Still Need Protection from Abusive Credit Products………………………………………………………………………14 IV. History of the Military Lending Act and DoD Regulations………………18 V. Impact of MLA on Covered Consumer Credit……………………………..21 VI. Maps Illustrate Impact of Military Lending Act at Selected Bases……...31 VII. Bank Payday Loans Not Covered by MLA Rules………………………..49 VIII. No Impact on Military Installment Loans……………………………….61 IX. No Impact on State Regulation of Lending to Non-resident Borrowers…………………………………………………………………….73 X. No Impact on Retail Installment Sales Credit or Rent-to-Own…………...76 XI. Enforcement Tools for Military Lending Act Must be Strengthened……81 XII. No Impact of Military Lending Act Allotment Protections……………...94 XIII. Impact of MLA on Advocacy to Protect all Americans……………….102 XIV. Access to Relief Society Assistance and Better Financial Options……104 2 The Military Lending Act Five Years Later Impact On Servicemembers, the High-Cost Small Dollar Loan Market, and the Campaign against Predatory Lending by Jean Ann Fox Consumer Federation of America May 29, 2012 Five years ago the Department of Defense -

HISTORY of NEUROLOGY Guillaume-Benjamin Amand Duchenne, MD (1806-1875)

HISTORY OF NEUROLOGY Guillaume-Benjamin Amand Duchenne, MD (1806-1875) “Master of the Master” Richard J. Barohn, MD February 10, 2017 Guillaume-Benjamin-Amand Duchenne 1806-1875 • Born: Boulogne-sur-Mer, France • Aka Duchenne “De Boulogne” • One of the greatest clinicians in 19th century • Charcot called him his Master! • Family of fishermen/sea captains • Father received Légion d’Honneur from Napolean for valor as sea captain in French-British wars • Paris medical school grad 1831; studied under Laënnec, Dupuytren; returned to Boulogne for 11 years but practice was limited so he returned to Paris at age 36 (1842) • Began seeing patients in charity clinics/large public hospitals/asylums • Never had hospital or university appointment • Over time his skill analyzing clinical problems was recognized by Trousseau, Charcot, Aran, Broca • Visited hospitals with his electrical stimulation gadget • Continuously tried new ways of testing nervous functions • Goal: discovery of new facts about the nervous diseases Duchenne de Boulogne Major Contributions 1. Observations and detailed clinical descriptions 2. Electrical Stimulation 3. Biopsy & Histology/Neuropathology 4. Use of medical photography Did first clinical-electrical-pathologic correlations Also a gadget-guy And a biomarker guy Duchenne de Boulogne Some of His Important Clinical Observations & Descriptions: 1. Tabetic Locomotor Ataxia – Distinguished it from Friedrich from locomotor ataxia 2. Deduced Poliomyelitis was a disease of motor nerve cells in spinal cord 3. Described lead poisoning & response to electrical stimulation 4. Described Progressive Muscular Atrophy – Also described by Francois Aran 1850 who acknowledged Duchenne’s help 5. Described Progressive Bulbar Palsy 6. Erb-Duchenne Palsy – upper trunk brachial plexus in babies from childbirth 7. -

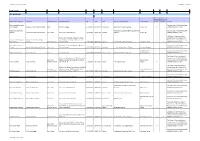

ROYAL GALLERY FIRST WORLD WAR Name (As On

Houses of Parliament War Memorials Royal Gallery, First World War ROYAL GALLERY FIRST WORLD WAR Also in Also in Westmins Commons Name (as on memorial) Full Name MP/Peer/Son of... Constituency/Title Birth Death Rank Regiment/Squadron/Ship Place of Death ter Hall Chamber Sources Shelley Leopold Laurence House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Baron Abinger Shelley Leopold Laurence Scarlett Peer 5th Baron Abinger 01/04/1872 23/05/1917 Commander Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve London, UK X MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Humphrey James Arden 5th Battalion, London Regiment (London Rifle House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Adderley Humphrey James Arden Adderley Son of Peer 3rd son of 2nd Baron Norton 16/10/1882 17/06/1917 Rifleman Brigade) Lincoln, UK MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) The House of Commons Book of Bodmin 1906, St Austell 1908-1915 / Eldest Remembrance 1914-1918 (1931); Thomas Charles Reginald Thomas Charles Reginald Agar- son of Thomas Charles Agar-Robartes, 6th House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Agar-Robartes Robartes MP / Son of Peer Viscount Clifden 22/05/1880 30/09/1915 Captain 1st Battalion, Coldstream Guards Lapugnoy, France X X MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Horace Michael Hynman Only son of 1st Viscount Allenby of Meggido House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Allenby Horace Michael Hynman Allenby Son of Peer and of Felixstowe 11/01/1898 29/07/1917 Lieutenant 'T' Battery, Royal Horse Artillery Oosthoek, Belgium MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Aeroplane over House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Francis Earl Annesley Francis Annesley Peer 6th Earl Annesley 25/02/1884 05/11/1914 -

The History, Literature & Images of World War

William Reese Company AMERICANA • RARE BOOKS • LITERATURE AMERICAN ART • PHOTOGRAPHY __________ 409 TEMPLE STREET NEW HAVEN, CONNECTICUT 06511 (203) 789-8081 FAX (203) 865-7653 [email protected] www.williamreesecompany.com The War to End All Wars: The History, Literature & Images of World War One November marked the centennial of the end of the First World War. The “war to end all wars” took the lives of some fifteen million soldiers and civilians, and injured, maimed, and scarred tens of millions more. What follows is a selection of material drawn from our Literature and Americana departments related to the Great War. Included are novels, plays, and poetry, as well as descriptions of military preparations, political messages, and the treaties that ended the war (and unintentionally paved the way for World War Two). There are also several panoramic photographs, including images of African-American troops in Maryland training for European service, and other American troops patrolling the Mexican border as part of the “Punitive Expedition” against Pancho Villa. 1. [Beerbohm, Max]: Shaw, George Bernard: HEARTBREAK HOUSE, First edition. One of 125 copies on GREAT CATHERINE, AND PLAYLETS OF THE WAR. London: Constable Navarre. This copy, as often (but not and Co., 1925. Grey-green cloth lettered in gilt. Some foxing and mild soiling, always), has a portion of a line on page long narrow smudge to upper board; a good copy. 305 blacked out. Crosby served with the American Field Service and the Am- Fourth impression of the first UK edition (first printed in 1919 and preceded by bulance Corps during the Great War, the US edition). -

Army Abbreviations

Army Abbreviations Abbreviation Rank Descripiton 1LT FIRST LIEUTENANT 1SG FIRST SERGEANT 1ST BGLR FIRST BUGLER 1ST COOK FIRST COOK 1ST CORP FIRST CORPORAL 1ST LEADER FIRST LEADER 1ST LIEUT FIRST LIEUTENANT 1ST LIEUT ADC FIRST LIEUTENANT AIDE-DE-CAMP 1ST LIEUT ADJT FIRST LIEUTENANT ADJUTANT 1ST LIEUT ASST SURG FIRST LIEUTENANT ASSISTANT SURGEON 1ST LIEUT BN ADJT FIRST LIEUTENANT BATTALION ADJUTANT 1ST LIEUT REGTL QTR FIRST LIEUTENANT REGIMENTAL QUARTERMASTER 1ST LT FIRST LIEUTENANT 1ST MUS FIRST MUSICIAN 1ST OFFICER FIRST OFFICER 1ST SERG FIRST SERGEANT 1ST SGT FIRST SERGEANT 2 CL PVT SECOND CLASS PRIVATE 2 CL SPEC SECOND CLASS SPECIALIST 2D CORP SECOND CORPORAL 2D LIEUT SECOND LIEUTENANT 2D SERG SECOND SERGEANT 2LT SECOND LIEUTENANT 2ND LT SECOND LIEUTENANT 3 CL SPEC THIRD CLASS SPECIALIST 3D CORP THIRD CORPORAL 3D LIEUT THIRD LIEUTENANT 3D SERG THIRD SERGEANT 3RD OFFICER THIRD OFFICER 4 CL SPEC FOURTH CLASS SPECIALIST 4 CORP FOURTH CORPORAL 5 CL SPEC FIFTH CLASS SPECIALIST 6 CL SPEC SIXTH CLASS SPECIALIST ACTG HOSP STEW ACTING HOSPITAL STEWARD ADC AIDE-DE-CAMP ADJT ADJUTANT ARMORER ARMORER ART ARTIF ARTILLERY ARTIFICER ARTIF ARTIFICER ASST BAND LDR ASSISTANT BAND LEADER ASST ENGR CAC ASSISTANT ENGINEER ASST QTR MR ASSISTANT QUARTERMASTER ASST STEWARD ASSISTANT STEWARD ASST SURG ASSISTANT SURGEON AUX 1 CL SPEC AUXILARY 1ST CLASS SPECIALIST AVN CADET AVIATION CADET BAND CORP BAND CORPORAL BAND LDR BAND LEADER BAND SERG BAND SERGEANT BG BRIGADIER GENERAL BGLR BUGLER BGLR 1 CL BUGLER 1ST CLASS BLKSMITH BLACKSMITH BN COOK BATTALION COOK BN -

The Above Photo, from the Illustrated War News of September 1915

The above photo, from the Illustrated War News of September 1915, exposes how many cameras of that era were unsuited to action shots, but the caption suggests another reason, that the photographer realised the batsman had an eye on hitting the ball into his stomach! Whatever, it is a seasonal frontispiece and several items inside mention cricket. One article, about disturbing the eternal rest of one of the “Several Battalion Commanders” in my talk last May is definitely not cricket but telling the story will hopefully result in a reverent solution see Page 15. Editor’s Musing survived to become manager of Martins Bank in Kendal. In my report on the talk given by Clive The other Harris (Page 20) I refer to him getting brother who “under the skins of the individuals in his served was talk”. This is a feeling I experience when George Bargh. researching officers for presentations. The family (5 There is a compulsive feeling to pursue brothers, two all means to gather information to sisters) was understand and portray the individuals. I brought up at muse about them when my mind has Proctor’s Farm nothing better to think about. in Wray and Having delivered my talk last May, George was Gilbert Mackereth went out of my third youngest. At the age of 12 and after thoughts and in a sense the visit to his attending Wray School, George went to grave in San Sebastian last summer was live with his newly married eldest sister final closure. To be subsequently Hannah and her husband George Platts, advised of the threat to his earthly a butcher in Halifax. -

Two Colored Women with the American Expeditionary Forces

I. and II. Col. Franklin A. Denison and Lt. Col. Otis B. Duncan, the highest ranking colored officers in France. III. Col. Charles Young, the highest ranking colored officer in the United States Army. IV. Major Rufus M. Stokes. V. Major Joseph H. Ward. Two Colored Women With the American Expeditionary Forces By ADDIE W. HUNTON and KATHRYN M. JOHNSON Illustrated BBOOKLYN EAGLE PRESS BROOKLYN, NEW YORK SSOS06 Dedicated to the women of OUT race, who gave so trustingly and courageously the strongest of their young manhood to suffer and to die for the cause of freedom. With recognition and thanks to the authors quoted in this volume and to the men of the A. E. F. who have contributed so willingly and largely to the story herein related. Contents fFOREWORD 5 fTHE CALL AND THE ANSWER 9 fFiRST DAYS IN FRANCE 15 *THE Y.M.C.A. AND OTHER WELFARE ORGANIZATIONS 22 *THE COMBATANT TROOPS 41 fNON-COMBATANT TROOPS 96 fPiONEER INFANTRIES 112 fOvER THE CANTEEN IN FRANCE 135 {THE LEAVE AREA 159 *RELATIONSHIPS WITH THE FRENCH 182 *EDUCATION 199 fTHE SALVATION OF Music OVERSEAS 217 *RELJGIOUS LIFE AMONG THE TROOPS 227 fREBURYING THE DEAD 233 fSTRAY DAYS 241 *AFTERTHOUGHT . 253 t By Addie W. Hunton. * By Kathryn M. Johnson. Foreword T3EMARKABLE achievements are worthy of remarka- AX ble acclaim. This justifies our desire to add still another expression to those already written relative to the career of the colored American soldiers in the late World War. The heroic devotion and sacrifice of that career have won appreciative expressions from those who, from a personal point of view, know but little of the details. -

Erb-Duchenne Brachial Plexus Palsy

A Review Paper Hyphenated History: Erb-Duchenne Brachial Plexus Palsy Carrie Schmitt, BA, Charles T. Mehlman, DO, MPH, and A. Ludwig Meiss, MD Unlike the invasive electropuncture method recently devel- Abstract oped by Magendie and Jean-Baptiste Sarlandiere (1781–1838), Throughout history, the discoveries of their predecessors Duchenne invented a portable machine that used surface elec- have led physicians to revolutionary advances in the trodes to minimize the spread of electric current, resulting understanding and practice of medicine. The result is a in less pain and tissue damage to the patient.2,3,5 Duchenne plethora of hyphenated eponyms paying tribute to indi- referred to his process as local faradization, giving credit to viduals connected through time by a common interest. Michael Faraday (1791–1867), the scientist who invented the The history of Guillaume Duchenne de Boulogne, the 3,4 “father of electrotherapy and electrodiagnosis,” and induction coil in 1831. In 1842, Duchenne moved to Paris to Wilhelm Heinrich Erb, the “father of neurology,” offers explore the uncharted territories this field offered. insight into the personal and professional lives of these Known as Duchenne de Boulogne in Paris, he was consid- astute clinicians and their collaborative medical break- ered an eccentric by his peers for his provincial mannerisms through in the area of neurologic paralysis affecting the until many years later, when his work and expertise earned upper limbs. him international attention.2,6 Without any official position with a hospital or university, Duchenne made his rounds by DUCHENNE following his patients from hospital to hospital for years.2,5,6 French physician Guillaume Benjamin Armand Duchenne Through these extensive clinical studies and observations, he lived from 1806 to 1875.