HSR 42 (2017)2 Zelko Scaling Greenpeace from Local Activism to Global Governance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bc Historic News

British Columbia Journal of the British Columbia Historical Federation | Vol.39 No. 4 | $5.00 This Issue: Tribute to Anne Yandle | Fraser Canyon Park | Bells | and More British Columbia History British Columbia Historical Federation Journal of the British Columbia Historical A charitable society under the Income Tax Act Organized 31 October 1922 Federation Published four times a year. ISSN: print 1710-7881 online 1710-792X PO Box 5254, Station B., Victoria BC V8R 6N4 Under the Distinguished Patronage of Her Honour British Columbia History welcomes stories, studies, The Honourable Iona Campagnolo. PC, CM, OBC and news items dealing with any aspect of the Lieutenant-Governor of British Columbia history of British Columbia, and British Columbians. Honourary President Please submit manuscripts for publication to the Naomi Miller Editor, British Columbia History, John Atkin, 921 Princess Avenue, Vancouver BC V6A 3E8 Officers e-mail: [email protected] President Book reviews for British Columbia History, Patricia Roy - 602-139 Clarence St., Victoria, BC, V8V 2J1 Please submit books for review to: [email protected] Frances Gundry PO Box 5254, Station B., Victoria BC V8R 6N4 First Vice President Tom Lymbery - 1979 Chainsaw Ave., Gray Creek, BC, V0B 1S0 Phone 250.227.9448 Subscription & subscription information: FAX 250.227.9449 Alice Marwood [email protected] 8056 168A Street, Surrey B C V4N 4Y6 Phone 604-576-1548 Second Vice President e-mail [email protected] Webb Cummings - 924 Bellevue St., New Denver, BC, V0G 1S0 Phone 250.358.2656 [email protected] -

Nine Meals from Anarchy Oil Dependence, Climate Change and the Transition to Resilience

Nine Meals from Anarchy Oil dependence, climate change and the transition to resilience new economics foundation nef is an independent think-and-do tank that inspires and demonstrates real economic well-being. We aim to improve quality of life by promoting innovative solutions that challenge mainstream thinking on economic, environmental and social issues. We work in partnership and put people and the planet first. nef centres for: global thriving well-being future interdependence communities economy nef (the new economics foundation) is a registered charity founded in 1986 by the leaders of The Other Economic Summit (TOES), which forced issues such as international debt onto the agenda of the G8 summit meetings. It has taken a lead in helping establish new coalitions and organisations such as the Jubilee 2000 debt campaign; the Ethical Trading Initiative; the UK Social Investment Forum; and new ways to measure social and economic well-being. new economics foundation Nine Meals from Anarchy Oil dependence, climate change and the transition to resilience Schumacher Lecture, 2008 Schumacher North, Leeds, UK by Andrew Simms new economics foundation ‘Such essays cannot awat the permanence of the book. They do not belong n the learned journal. They resst packagng n perodcals.’ Ivan Illich Contents ‘Apparently sold financal nsttutons have tumbled. So, what else that we currently take for granted mght be prone to sudden collapse?’ Schumacher Lecture, 4 October 2008 Delivered by Andrew Simms Schumacher North, Leeds, UK To begin with – the world as it is 1 Nine meals from anarchy 3 Enough of problems 17 Conclusion 30 Endnotes 32 ‘Perhaps we cannot rase the wnds. -

Letter to Senator Leahy

FOUNDATION EARTH Rethinking society from the ground up! January 27, 2014 The Hon. Patrick Leahy, Chairman Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on Foreign Operations Dirksen Senate Office Building Washington, D.C. 20510 Re: Your Leadership on World Bank Reforms Dear Mr. Chairman: We are writing to express our enormous appreciation for your successful efforts to include in the Foreign Operations Appropriations extraordinarily important language about the need for oversight of the World Bank’s activities, especially in regard to its attempt to return to mega-hydro dam construction, as well as the activities of other international financial institutions in this regard. On behalf of the more than 80 signers of our May 24, 2013 letter to you, we thank you and recognize the leadership that you showed, not just on the World Bank but also on the other international financial institutions. The provisions on safeguarding intact tropical rainforests from industrial logging and extraction have been urgently needed as have the directives on human rights protections and forced relocations. We will work to see that the Obama Administration vigorously implements these provisions. Sincerely, Randy Hayes, Executive Director Brent Blackwelder, President Emeritus Foundation Earth Friends of the Earth Note: Attached is the extensive list of signers of the May 24, 2013 letter calling for World Bank President Kim to not finance giant rainforest & river destroying dams. We have notified these concerned citizens that you took decisive action. 660 Pennsylvania Avenue S.E. Suite 302; Washington, DC 20003 USA Phone 202-547-9359 www.FDNEARTH.org Fax 202-547-9429 Signers of the May 24, 2013 letter calling for World Bank President Kim to not finance giant rainforest & river destroying dams. -

Nuclear Flashback

u@ THE RETURN TO AMCHITKA 1436 U Street, NW Report of a Greenpeace Scientific Expedition to Washington, DC 20009 1-800-326-0959 Amchitka Island, Alaska-Site of the Largest http://www.greenpeace.org/-usa Underground l\Juclear Test In U.S. History A Greenpeace Report by Pam Miller Scientific Adviser Norman Buske Greenpeace was compelled to return to Purpose Amchitka in June 1996 to conduct an independent chitka Island, Alaska was the site of three underground nudcar tests: investigation of the nuclear detonation sites at Long Sho t, an 80 kiloto n test (80,000 tons TNT equivalent) in 1965; Amchitka. AE ilrow, a 1 megaton test (1,000,000 tons TNT equivalent) in 1969; and Cannikin, a 5 megaton test (5,000,000 tons TNT equivalent) in 1971. Project Cannikin was the largest underground nuclear test in U.S. history. Greenpeace was founded by a group of activists who sailed from Vancouver, Canada toward Am chitka Island in an attempt to stop the Cannikin blast through non-violent direct action. Twenty-five years after the founding of Greenpeace, concerns about the legacy of the unstoppable nuclear explosion dubbed Cannikin beckoned us to return to investigate the impacts of nuclear testing at Amchitka. The International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War (IPPNW) calculaled the cum ulative inventori es of radioactive isotopes generated from underground nuclear tests th roughout the world. They estimate a fission yield of 0.1 megacurie per megaton explosive yi eld for strontium-90, 0.1 G megacurie per megaton for cesium- J37, and un flss io ned plutonium-239 at 150 curies per test. -

IJTM/IJCEE PAGE Templatev2

Int. J. Green Economics, Vol. 1, Nos. 1/2, 2006 201 Green economics: an introduction and research agenda Derek Wall Goldsmiths College, University of London New Cross, London SE14 6NW, UK E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Green economics: An introduction and research agenda, examines the historical evolution of green economics, a discourse which is marked by antipathy to the foundational assumptions of conventional market based economics. Green opposition to growth and the market is identified along with values of ecological sustainability, social justice, decentralisation and peace. To move beyond a critical account, green economics, as a discipline, needs to establish a research agenda based on: 1 examining global political economy 2 developing forms of regulation beyond the market and the state 3 examining the transition to such an alternative economy. Keywords: green economics; global political economy; regulation; transition; economic growth; anti-capitalism; Marx; open source; usufruct; commons. Reference to this paper should be made as follows: Wall, D. (2006) ‘Green economics: an introduction and research agenda’, Int. J. Green Economics, Vol. 1, Nos. 1/2, pp.201–214. Biographical notes: Derek Wall teaches Political Economy at Goldsmiths College, University of London in the Politics Department. His PhD, ‘The Politics of Earth First! UK’ was completed in 1998. He has published six books on green economics including, most recently, Babylon and Beyond: The Economics of Anti-Capitalist, Anti-Globalist and Radical Green Movements (Pluto 2005). He is a long standing eco-socialist and the founder of the Association of Socialist Greens. He is a member of International Zen Association. His next book, Shopping Without Money, will look at a wide variety of non-monetary forms of economic regulation. -

Bob Farquhar

1 2 Created by Bob Farquhar For and dedicated to my grandchildren, their children, and all humanity. This is Copyright material 3 Table of Contents Preface 4 Conclusions 6 Gadget 8 Making Bombs Tick 15 ‘Little Boy’ 25 ‘Fat Man’ 40 Effectiveness 49 Death By Radiation 52 Crossroads 55 Atomic Bomb Targets 66 Acheson–Lilienthal Report & Baruch Plan 68 The Tests 71 Guinea Pigs 92 Atomic Animals 96 Downwinders 100 The H-Bomb 109 Nukes in Space 119 Going Underground 124 Leaks and Vents 132 Turning Swords Into Plowshares 135 Nuclear Detonations by Other Countries 147 Cessation of Testing 159 Building Bombs 161 Delivering Bombs 178 Strategic Bombers 181 Nuclear Capable Tactical Aircraft 188 Missiles and MIRV’s 193 Naval Delivery 211 Stand-Off & Cruise Missiles 219 U.S. Nuclear Arsenal 229 Enduring Stockpile 246 Nuclear Treaties 251 Duck and Cover 255 Let’s Nuke Des Moines! 265 Conclusion 270 Lest We Forget 274 The Beginning or The End? 280 Update: 7/1/12 Copyright © 2012 rbf 4 Preface 5 Hey there, I’m Ralph. That’s my dog Spot over there. Welcome to the not-so-wonderful world of nuclear weaponry. This book is a journey from 1945 when the first atomic bomb was detonated in the New Mexico desert to where we are today. It’s an interesting and sometimes bizarre journey. It can also be horribly frightening. Today, there are enough nuclear weapons to destroy the civilized world several times over. Over 23,000. “Enough to make the rubble bounce,” Winston Churchill said. The United States alone has over 10,000 warheads in what’s called the ‘enduring stockpile.’ In my time, we took care of things Mano-a-Mano. -

Greenpeace, Earth First! and the Earth Liberation Front: the Rp Ogression of the Radical Environmental Movement in America" (2008)

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Senior Honors Projects Honors Program at the University of Rhode Island 2008 Greenpeace, Earth First! and The aE rth Liberation Front: The rP ogression of the Radical Environmental Movement in America Christopher J. Covill University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Covill, Christopher J., "Greenpeace, Earth First! and The Earth Liberation Front: The rP ogression of the Radical Environmental Movement in America" (2008). Senior Honors Projects. Paper 93. http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog/93http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog/93 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at the University of Rhode Island at DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Greenpeace, Earth First! and The Earth Liberation Front: The Progression of the Radical Environmental Movement in America Christopher John Covill Faculty Sponsor: Professor Timothy Hennessey, Political Science Causes of worldwide environmental destruction created a form of activism, Ecotage with an incredible success rate. Ecotage uses direct action, or monkey wrenching, to prevent environmental destruction. Mainstream conservation efforts were viewed by many environmentalists as having failed from compromise inspiring the birth of radicalized groups. This eventually transformed conservationists into radicals. Green Peace inspired radical environmentalism by civil disobedience, media campaigns and direct action tactics, but remained mainstream. Earth First’s! philosophy is based on a no compromise approach. -

Animal Rights …Legally, with Confidence

How to Do Animal Rights …legally, with confidence Second edition Contents About This Guide 5 Author & Email 5 Animal Rights Motto 6 1 Introduction 1.1 The Broad Setting 7 - the big problem. 1.2 Mass Extinction 9 - we live in the Sixth Extinction. 1.3 Animal Holocaust 11 - we live in an enduring and worsening Animal Holocaust. 1.4 World Scientists' Warning to Humanity 12 - scientists attempt to alert the world to the impending catastrophe. 2 Philosophy: Key Topics 2.1 Animal Rights 16 - know what animal rights are. 2.2 Equal Consideration 21 - are animal and human moral interests equally important? 2.3 Animal Ethics 23 - defend your animal rights activism rationally. 2.4 Consequentialism 29 - the morality of your action depends only on its consequences. 2.5 Deontology 30 - the morality of your action depends only on doing your duty. 2.6 Virtue Ethics 31 - the morality of your action depends only on your character. 2.7 Comparing Philosophies 33 - comparing animal rights with ethics, welfare & conservation. 2.8 Deep Ecology 37 - contrasts with animal rights and gives it perspective. How to Do Animal Rights 3 Campaigning: Methods for Animal Rights 3.1 How to Start Being Active for Animal Rights 40 - change society for the better. 3.2 Civil Disobedience 46 - campaign to right injustice. 3.3 Direct Action 49 - a stronger form of civil disobedience. 3.4 Action Planning 55 - take care that your activities are successful. 3.5 Lobbying 60 - sway the prominent and influential. 3.6 Picketing 65 - protest your target visibly and publicly. -

Native People's Spirituality and the Marketplace

Native People’s DO YOU THINK you are “Indian at heart” or were an Indian in a past life? spirituality DO YOU A D MIRE native ways and want to incorporate them into your life and do your own version of a sweat lodge or a vision quest? HAVE YOU SEEN ads, books, and websites that offer to train you to be come a shaman in an easy number of steps, a few days on the weekend, or for a fee? and HAVE YOU REALLY thought this all the way through? the Marketplace RECOMMENDED READING Fantasies of the Master Race - Literature, Cinema and the colonization of American Indians, by Ward Churchill (1992) (The book this pamphlet is largely made up of excerpts from.) Indians Are Us? by Ward Churchill (Common Courage Press, 1994) Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, by Dee Brown (1971) Blood of the Land, by Rex Weyler (New Society Publishers, 1992) A Basic Call to Consciousness: the Haudenosaunee Address to the Western World (Akwesasne Notes) A Tortured People: The Politics of Colonization, by Howard Adams (1995) Lakota Woman, by Mary Crow Dog and Richard Erdos All Our Relations: Native Struggles for Land and Life, by Winona LaDuke Websites: http://www.newagefraud.org/ - native site about Plastic Shamanism http://intercontinentalcry.org/ - Reporting on Indigenous Struggles The following pamphlet can only serve as an http://warriorpublications.com/ - Warrior Publications introduction to the multi-faceted relationship between http://wiinimikiikaa.wordpress.com/ - Revolutionary Indigenous Resistance colonizer and colonized. It is addressed primarily to the so called “New Age” movement. There is nothing “healing” http://indigenousaction.org/ - Indigenous Action Media in stealing from an already dispossessed people and http://blackmesais.org/ - Black Mesa Indigenous Support nothing “New” in finding new means and justifications http://wsdp.org/ - Western Shoshone Defense Project to do so. -

Historical Timeline for Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge

Historical Timeline Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge Much of the refuge has been protected as a national wildlife refuge for over a century, and we recognize that refuge lands are the ancestral homelands of Alaska Native people. Development of sophisticated tools and the abundance of coastal and marine wildlife have made it possible for people to thrive here for thousands of years. So many facets of Alaska’s history happened on the lands and waters of the Alaska Maritime Refuge that the Refuge seems like a time-capsule story of the state and the conservation of island wildlife: • Pre 1800s – The first people come to the islands, the Russian voyages of discovery, the beginnings of the fur trade, first rats and fox introduced to islands, Steller sea cow goes extinct. • 1800s – Whaling, America buys Alaska, growth of the fox fur industry, beginnings of the refuge. • 1900 to 1945 – Wildlife Refuge System is born and more land put in the refuge, wildlife protection increases through treaties and legislation, World War II rolls over the refuge, rats and foxes spread to more islands. The Aleutian Islands WWII National Monument designation recognizes some of these significant events and places. • 1945 to the present – Cold War bases built on refuge, nuclear bombs on Amchitka, refuge expands and protections increase, Aleutian goose brought back from near extinction, marine mammals in trouble. Refuge History - Pre - 1800 A World without People Volcanoes push up from the sea. Ocean levels fluctuate. Animals arrive and adapt to dynamic marine conditions as they find niches along the forming continent’s miles of coastline. -

Environmental Activism on the Ground: Small Green and Indigenous Organizing

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2019-01 Environmental Activism on the Ground: Small Green and Indigenous Organizing University of Calgary Press Clapperton, J., & Piper, L. (2019). Environmental activism on the ground: small green and indigenous organizing. Calgary, AB: University of Calgary Press. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/109482 book https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca ENVIRONMENTAL ACTIVISM ON THE GROUND: Small Green and Indigenous Organizing Edited by Jonathan Clapperton and Liza Piper ISBN 978-1-77385-005-4 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This open-access work is published under a Creative Commons licence. -

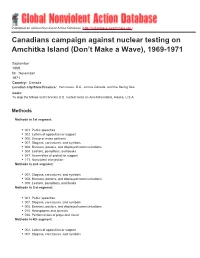

Canadians Campaign Against Nuclear Testing on Amchitka Island (Don’T Make a Wave), 1969-1971

Published on Global Nonviolent Action Database (http://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu) Canadians campaign against nuclear testing on Amchitka Island (Don’t Make a Wave), 1969-1971 September 1969 to: November 1971 Country: Canada Location City/State/Province: Vancouver, B.C., across Canada, and the Bering Sea Goals: To stop the Milrow and Cannikin U.S. nuclear tests on Amchitka Island, Alaska, U.S.A. Methods Methods in 1st segment: 001. Public speeches 002. Letters of opposition or support 006. Group or mass petitions 007. Slogans, caricatures, and symbols 008. Banners, posters, and displayed communications 009. Leaflets, pamphlets, and books 047. Assemblies of protest or support 171. Nonviolent interjection Methods in 2nd segment: 007. Slogans, caricatures, and symbols 008. Banners, posters, and displayed communications 009. Leaflets, pamphlets, and books Methods in 3rd segment: 001. Public speeches 007. Slogans, caricatures, and symbols 008. Banners, posters, and displayed communications 010. Newspapers and journals 036. Performances of plays and music Methods in 4th segment: 002. Letters of opposition or support 007. Slogans, caricatures, and symbols 008. Banners, posters, and displayed communications 010. Newspapers and journals Methods in 5th segment: 001. Public speeches 002. Letters of opposition or support 005. Declarations of indictment and intention › Announced intention to nonviolently interject in test zone 007. Slogans, caricatures, and symbols 008. Banners, posters, and displayed communications 010. Newspapers and journals 011. Records, radio, and television 041. Pilgrimages 047. Assemblies of protest or support 171. Nonviolent interjection Methods in 6th segment: 002. Letters of opposition or support 005. Declarations of indictment and intention › Announced intention to nonviolently interject in test zone 006.