Samoa: 2019 Article IV Consultation-Press Release

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Currency Codes

Country Capital Currency Name Code Afghanistan Kabul Afghanistan Afghani AFN Albania Tirana Albanian Lek ALL Algeria Algiers Algerian Dinar DZD American Samoa Pago Pago US Dollar USD Andorra Andorra Euro EUR Angola Luanda Angolan Kwanza AOA Anguilla The Valley East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antarctica None East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda St. Johns East Caribbean Dollar XCD Argentina Buenos Aires Argentine Peso ARS Armenia Yerevan Armenian Dram AMD Aruba Oranjestad Aruban Guilder AWG Australia Canberra Australian Dollar AUD Austria Vienna Euro EUR Azerbaijan Baku Azerbaijan New Manat AZN Bahamas Nassau Bahamian Dollar BSD Bahrain Al-Manamah Bahraini Dinar BHD Bangladesh Dhaka Bangladeshi Taka BDT Barbados Bridgetown Barbados Dollar BBD Belarus Minsk Belarussian Ruble BYR Belgium Brussels Euro EUR Belize Belmopan Belize Dollar BZD Benin Porto-Novo CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Bermuda Hamilton Bermudian Dollar BMD Bhutan Thimphu Bhutan Ngultrum BTN Bolivia La Paz Boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Sarajevo Marka BAM Botswana Gaborone Botswana Pula BWP Bouvet Island None Norwegian Krone NOK Brazil Brasilia Brazilian Real BRL British Indian Ocean Territory None US Dollar USD Bandar Seri Brunei Darussalam Begawan Brunei Dollar BND Bulgaria Sofia Bulgarian Lev BGN Burkina Faso Ouagadougou CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Burundi Bujumbura Burundi Franc BIF Cambodia Phnom Penh Kampuchean Riel KHR Cameroon Yaounde CFA Franc BEAC XAF Canada Ottawa Canadian Dollar CAD Cape Verde Praia Cape Verde Escudo CVE Cayman Islands Georgetown Cayman Islands Dollar KYD _____________________________________________________________________________________________ -

Currency Rates 2014-2015 – Rolling 12 Month Average

Currency rates 2014-2015 – Rolling 12 Month Average Currency Code 15/04/14 15/05/14 15/06/14 15/07/14 15/08/14 15/09/14 15/10/14 15/11/14 15/12/14 15/01/15 15/02/15 15/03/15 Australia Dollar AUD 0.8931 0.9007 0.9074 0.9139 0.9162 0.9184 0.9205 0.9217 0.9234 0.9248 0.9276 0.9289 Bahrain Dinar BHD 0.3116 0.3129 0.3148 0.3178 0.3191 0.3193 0.3180 0.3167 0.3150 0.3134 0.3106 0.3068 Britain Pound GBH 0.5154 0.5132 0.5131 0.5126 0.5120 0.5113 0.5092 0.5081 0.5072 0.5077 0.5064 0.5051 Canada Dollar CAD 0.8736 0.8823 0.8924 0.9032 0.9109 0.9161 0.9185 0.9204 0.9230 0.9251 0.9259 0.9251 China Yuan CNY 5.0553 5.0819 5.1194 5.1736 5.1976 5.2015 5.1827 5.1631 5.1439 5.1272 5.0932 5.0389 Denmark Kroner DKK 4.5741 4.5692 4.5928 4.6228 4.6404 4.6523 4.6534 4.6612 4.6733 4.7088 4.7348 4.7878 European Community Euro EUR 0.6132 0.6124 0.6155 0.6196 0.6219 0.6236 0.6239 0.6250 0.6268 0.6318 0.6355 0.6426 Fiji Dollar FJ D 1.5339 1.5416 1.5518 1.5622 1.5661 1.5692 1.5693 1.5699 1.5688 1.5673 1.5639 1.5583 French Polynesia Franc XPF 73.1675 73.0734 73.4489 73.9347 74.2226 74.4277 74.4707 74.6081 74.8172 75.4201 75.8505 76.7147 Hong Kong Dollar HKD 6.4103 6.4356 6.4751 6.5365 6.5629 6.5656 6.5401 6.5128 6.4795 6.4461 6.3873 6.3096 India Rupee INR 50.1763 50.7103 51.1397 51.6807 51.8547 51.7080 51.3998 51.0851 50.9015 50.6313 50.1609 49.6534 Indonesia Rupiah IDR 9,142.9017 9,304.7083 9,493.6458 9,698.4908 9,822.5217 9,873.8358 9,909.4217 9,906.6033 9,895.5325 9,864.7367 9,832.0200 9,833.5850 Japan Yen JPY 82.9540 83.2486 84.2967 85.2286 85.9152 86.4854 86.6823 -

Exchange Rate Statistics

Exchange rate statistics Updated issue Statistical Series Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics 2 This Statistical Series is released once a month and pub- Deutsche Bundesbank lished on the basis of Section 18 of the Bundesbank Act Wilhelm-Epstein-Straße 14 (Gesetz über die Deutsche Bundesbank). 60431 Frankfurt am Main Germany To be informed when new issues of this Statistical Series are published, subscribe to the newsletter at: Postfach 10 06 02 www.bundesbank.de/statistik-newsletter_en 60006 Frankfurt am Main Germany Compared with the regular issue, which you may subscribe to as a newsletter, this issue contains data, which have Tel.: +49 (0)69 9566 3512 been updated in the meantime. Email: www.bundesbank.de/contact Up-to-date information and time series are also available Information pursuant to Section 5 of the German Tele- online at: media Act (Telemediengesetz) can be found at: www.bundesbank.de/content/821976 www.bundesbank.de/imprint www.bundesbank.de/timeseries Reproduction permitted only if source is stated. Further statistics compiled by the Deutsche Bundesbank can also be accessed at the Bundesbank web pages. ISSN 2699–9188 A publication schedule for selected statistics can be viewed Please consult the relevant table for the date of the last on the following page: update. www.bundesbank.de/statisticalcalender Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics 3 Contents I. Euro area and exchange rate stability convergence criterion 1. Euro area countries and irrevoc able euro conversion rates in the third stage of Economic and Monetary Union .................................................................. 7 2. Central rates and intervention rates in Exchange Rate Mechanism II ............................... 7 II. -

Forecasting Tala/USD and Tala/AUD of Samoa Using AR (1), and AR (4): a Comparative Study

Mathematics and Computers in Contemporary Science Forecasting Tala/USD and Tala/AUD of Samoa using AR (1), and AR (4): A Comparative Study Shamsuddin Ahmed Graduate School of Business MGM Khan School of Computing, Information and Mathematical Science Biman Prasad School of Economics The University of the South Pacific, Suva, Fiji [email protected] Abstract: - The paper studies the Autoregressive (AR) Models to forecast exchange rate of Samoan Tala/USD and Tala/AUD during the period of January 3 2008 to September 28 2012. We used daily exchange rate data to do our study. The performance of AR (1), and AR (4) model forecasting was measured by using varies error functions such as RSME Error, MAE, MAD, MAPE, Bias error, Variance error, and Co-variance error. The empirical findings suggest that AR (1) model is an effective tool to forecast the Tala/USD and Tala/AUD.. Key-Words: - AR (1), and AR (4) model, Exchange rate, RSME, MAE, MAD, MAPE, Bias error, Variance error, and Co-variance error 1 Introduction source of remittances, followed by Australia and the Samoa is located half way between Hawaii and United States. The tourism sector has also been New Zealand with the geographic coordinates of 13 growing steadily over the past few years, although 35 south and 172 20 west. The total area of the 2009 tsunami caused extensive damage to landmass is 2831 square kilometers. Samoa has got several hotels and resorts. Foreign development a tropical climate. It has got two main islands assistance in the form of loans, grants and direct aid (Savaii, Upolu) several smaller islands and is an important component of the economy. -

Opportunities to Improve Vanilla Value Chains for Small Pacific Island Countries

Opportunities to Improve Vanilla Value Chains for Small Pacific Island Countries Sisikula Palutea Sisifa, Betty Ofe-Grant and Christina Stringer About NZIPR The New Zealand Institute for Pacific Research (NZIPR) was launched in March 2016. Its primary role is to promote and support excellence in Pacific research. The NZIPR incorporates a wide network of researchers, research institutions and other sources of expertise in the Pacific Islands. Published by Opportunities to Improve Vanilla Value Chains for Small Pacific Island Countries Sisikula Palutea Sisifa, Betty Ofe-Grant and Christina Stringer ISBN: 978-0-473-48280-0 1 Acknowledgements We would like to thank our participants in the Cook Islands, Niue and Samoa who gave of their time to meet and talanoa with us. Each of them shared their passion for vanilla with us. They each have the desire to see the vanilla sector in their respective countries grow. They are keen to develop opportunities whereby the vanilla sector can be incorporated into commercial value chains and, importantly, for each country to be recognised for the quality of vanilla produced there. We learned a lot from each of those we met with. We hope our recommendations do justice to their vision for the industry. We also thank our New Zealand participants who provided key insights into possibilities in New Zealand for vanilla from the three Pacific Island countries. Our reviewers provided valuable comments, critique and suggestions towards improving the report. Thank you. Finally, we would like to express our appreciation to Alfred Hazelman, who worked tirelessly on this research project with us as our research assistant. -

The Parables of a Samoan Divine

THE PARABLES OF A SAMOAN DIVINE An Analysis of Samoan Texts of the 1860’s By Leulu F. Va’a A thesis submitted for the degTee of Master of Arts at the Australian National University. February 1987 1 Table of Contents Declaration iii Acknowledgements iv Abstract v 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1. The Nature of Hermeneutics 2 1.2. Historical Distance and Interpretation 3 1.3. Explanation and Understanding 4 1.4. Application of Hermeneutics 6 1.5. The Problem of Meaning 8 1.6. The Hymn Book 10 1.7. The Penisimani Manuscripts 12 1.8. The Thesis 17 2. Traditional Samoan Society 18 2.1. Political Organisation 26 2.2. Economic Organisation 29 2.3. Religious Organisation 31 3. The Coming of the Missionaries 39 3.1. Formation of the LMS 40 3.2. The Society’s Missionaries 41 3.3. Early Christian Influences 43 3.4. John Williams 45 3.5. Missionaries in Samoa 47 3.6. The Native Teachers 48 3.7. Reasons for Evangelical Success 51 3.8. Aftermath 54 4. The Folktales of Penisimani 57 4.1. Tala As Myths 57 4.2. Pemsimani’s Writings 59 4.3. Summary 71 5. The Parables of Penisimani 72 5.1. Leenhardt and Myth 73 5.2. Summary 86 6. The Words of Penisimani 87 6.1. The Power of the Word 88 6.2. Summary IOC 7. Myth, Parable and Signification 101 7.1. The Components of the Parable 102 7.1.1. The Cultural Element 103 7.1.2. The Christian Message 104 7.2. -

Exchange Rate Statistics April 2014

Exchange rate statistics April 2014 Statistical Supplement 5 to the Monthly Report Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics April 2014 2 Deutsche Bundesbank Wilhelm-Epstein-Strasse 14 60431 Frankfurt am Main Germany Postal address Postfach 10 06 02 60006 Frankfurt am Main The Statistical Supplement Exchange rate statistics is Germany published by the Deutsche Bundes bank, Frankfurt am Main, by virtue of section 18 of the Bundesbank Act. Tel +49 69 9566-0 It is available to interested parties free of charge. or +49 69 9566 8604 Further statistical data, supplementing the Monthly Report, Fax +49 69 9566 8606 or 3077 can be found in the follow ing supplements. http://www.bundesbank.de Banking statistics monthly Reproduction permitted only if source is stated. Capital market statistics monthly Balance of payments statistics monthly The German-language version of the Statis tical Supple- Seasonally adjusted ment Exchange rate statistics is published quarterly in business statistics monthly printed form. The Deutsche Bundesbank also publishes an updated monthly edition in German and in English on its Selected updated statistics are also available on the website. website. In cases of doubt, the original German-language Additionally, a CD-ROM containing roughly 40,000 pub- version is the sole authoritative text. lished Bundesbank time series, which is updated monthly, may be obtained for a fee from the Bundesbank‘s Statistical ISSN 2190–8990 (online edition) Information Management and Mathematical Methods Division or downloaded from the Bundesbank‘s ExtraNet Cut-off date: 8 April 2014. platform. Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics April 2014 3 Contents I Euro area and exchange rate stability convergence criterion 1 Euro-area member states and irrevocable euro conversion rates in the third stage of European Economic and Monetary Union ................................................................. -

Currencies Operating Under New Wire Payment Process

Currencies currently operating under the new wire payment process Curr en cy Bank Name Africa Code Kenyan Shilling KES Stanbic Bank, Nairobi Namibian Dollar NAD Standard Bank Namibia, Ltd, Windhoek South African Rand ZAR Standard Bank of South Africa, Johannesburg Curr en cy Bank Name Asia Code Hong Kong Dollar HKD Standard Chartered Bank, Hong Kong Indian Rupee** INR ICICI Bank, Local Western Union Agent Locations Japanese Yen JPY Standard Chartered Bank, Tokyo Singapore Dollar SGD The Bank of New York Mellon Thai Bhat THB HSBC Bank, Bangkok Curr en cy Australia / Oceania Code Bank Name Australian Dollar AUD HSBC Bank, Sydney Fiji Dollar FJD Westpac Banking Corporation, Suva New Zealand Dollar NZD Westpac Banking Corporation, Wellington Samoan Tala WST Westpac Bank Samoa Limited, Apia Tahitian (Central Polynesian) Franc XPF Banque de Polynesie, Papeete Vanuatu Vatu VUV Westpac Banking Corporation, Port Vila Curr en cy Bank Name Europe Code British Pound GBP HSBC Bank PLC, London Czech Republic Koruna CZK Ceskoslovenska Obchodni Banka Danish Krone DKK Danske Bank, Copenhagen Euro (Main)*** EUR HSBC Bank PLC, London Hungarian Forint HUF HSBC Bank PLC, London Latvian Lats LVL HSBC Bank PLC, London Lithuanian Litas LTL HSBC Bank PLC, London Norwegian Krone NOK Den Norske Bank, Oslo Polish Zloty PLN ING Bank, Poland Swedish Krona SEK Skandinaviska Enskilda Banken (SEB), Stockholm Swiss Fran c CHF Credit Suisse, Zurich Curr en cy Bank Name Middle East Code Bahrain Dinar BHD HSBC Bank PLC, London Israeli Shekel ILS HSBC Bank PLC, London Jordanian JOD HSBC Bank PLC, London Dinar Kuwaiti KWD HSBC Bank PLC, London Dinar Omani OMR HSBC Bank PLC, London Rial Qatari Rial QAR HSBC Bank PLC, London Turkish Lira TRY HSBC Bank PLC, London United Arab Emirates Dirham AED HSBC Bank PLC, London Curr en cy Bank Name North America Code Canadian Dollar CAD Royal Bank of Canada, Montreal Mexican Peso MXN HSBC Bank, Mexico United States Dollar (Main) USD Bank of New York Mellon, New York * Students in the Guangdong Province can utlize CITIC Bank in person. -

March 2021 Exchange Rate Report

EXCHANGE RATE DEVELOPMENTS MARCH 2021 H i g h l i g h t s : Change Policy Interest Rates Current Last Updated Commodity Prices Average Price Change Previous Month (basis point) (in USD) Reserve Bank of NZ 0.25% 0.00 April 14, 2021 crude oil (US$/bbl) $63.54 $0.48 $63.06 Reserve Bank of Australia 0.10% 0.00 April 6, 2021 whole milk powder (US$/t) $4,085.00 -$279.00 $4,364.00 US Federal Reserve 0.00 - 0.25% 0.00 March 17, 2021 European Central Bank 0.00% 0.00 March 11, 2020 Bank of England 0.10% 0.00 March 18, 2021 A. CURRENCY WATCH Germany to call for an immediate lockdown to avoid a New weights for the major currencies in the Samoa Tala currency basket possible third-wave of the Covid-19 pandemic; took effect on the 1st March following the endorsement of the Board of Markets feeling unease about fresh BREXIT tensions between th Directors in its meeting on the 26 February 2021. the European Union (EU) and United Kingdom (UK), following an unexpected decline in trade activities between the two The overall nominal effective value of the Samoan Tala nations soon after the UK left the EU in January. depreciated by 0.12 percent against the currency basket in March 2021. This nominal depreciation reflected the The Australian dollar (AUD) traded between US$0.78 and weakening of the Tala against the United States Dollar (by US$0.77, weakening against the USD due to: 0.45 percent), offsetting the Tala’s appreciation against the The greenback's robust gains and the unfavourable domestic New Zealand Dollar (by 0.82 percent), the Australian Dollar data releases including a drop in the GDP growth rate, the (by 0.04 percent) and Euro (by 1.05 percent). -

CCT Master Currency List-WU

Currency Bank Name Africa Code Kenyan Shilling KES Stanbic Bank, Nairobi Namibian Dollar NAD Standard Bank Namibia, Ltd, Windhoek South African Rand ZAR Standard Bank of South Africa, Johannesburg Currency Bank Name Asia Code Chinese Yuan CNY Citic Bank Hong Kong Dollar HKD Standard Chartered Bank, Hong Kong Indian Rupee INR ICICI Bank Japanese Yen JPY Standard Chartered Bank, Tokyo Singapore Dollar SGD The Bank of New York Mellon Thai Bhat THB HSBC Bank, Bangkok Currency Bank Name Australia / Oceania Code Australian Dollar AUD HSBC Bank, Sydney Fiji Dollar FJD Westpac Banking Corporation, Suva New Zealand Dollar NZD Westpac Banking Corporation, Wellington Samoan Tala WST Westpac Bank Samoa Limited, Apia Tahitian (Central Polynesian) Franc XPF Banque de Polynesie, Papeete Vanuatu Vatu VUV Westpac Banking Corporation, Port Vila Currency Bank Name Europe Code British Pound GBP HSBC Bank PLC, London Czech Republic Koruna CZK Ceskoslovenska Obchodni Banka Danish Krone DKK Danske Bank, Copenhagen Euro (Main)* EUR HSBC Bank PLC, London Hungarian Forint HUF HSBC Bank PLC, London Latvian Lats LVL HSBC Bank PLC, London Lithuanian Litas LTL HSBC Bank PLC, London Norwegian Krone NOK Den Norske Bank, Oslo Polish Zloty PLN ING Bank, Poland Swedish Krona SEK Skandinaviska Enskilda Banken (SEB), Stockholm Swiss Franc CHF Credit Suisse, Zurich Currency Bank Name Middle East Code Bahrain Dinar BHD HSBC Bank PLC, London Israeli Shekel ILS HSBC Bank PLC, London Jordanian Dinar JOD HSBC Bank PLC, London Kuwaiti Dinar KWD HSBC Bank PLC, London Omani Rial -

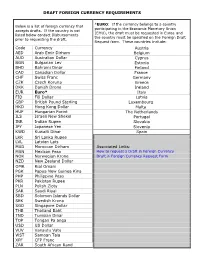

Below Is a List of Foreign Currency That Accepts Drafts

DRAFT FOREIGN CURRENCY REQUIREMENTS *EURO: If the currency belongs to a country Below is a list of foreign currency that participating in the Economic Monetary Union accepts drafts. If the country is not (EMU), the draft must be requested in Euros and listed below contact Disbursements the country must be specified on the Foreign Draft prior to requesting the draft. Request form. These countries include: Code Currency Austria AED Arab Emir Dirham Belgium AUD Australian Dollar Cyprus BGN Bulgarian Lev Estonia BHD Bahraini Dinar Finland CAD Canadian Dollar France CHF Swiss Franc Germany CZK Czech Koruna Greece DKK Danish Drone Ireland EUR Euro* Italy FJD Fiji Dollar Latvia GBP British Pound Sterling Luxembourg HKD Hong Kong Dollar Malta HUF Hungarian Forint The Netherlands ILS Israeli New Shekel Portugal INR Indian Rupee Slovakia JPY Japanese Yen Slovenia KWD Kuwaiti Dinar Spain LKR Sri Lanka Rupee LVL Latvian Lats MAD Moroccan Dirham Associated Links: MXN Mexican Peso How to request a Draft in Foreign Currency NOK Norwegian Krone Draft in Foreign Currency Request Form NZD New Zealand Dollar OMR Rial Omani PGK Papua New Guinea Kina PHP Philippine Peso PKR Pakistan Rupee PLN Polish Zloty SAR Saudi Riyal SBD Solomon Islands Dollar SEK Swedish Krona SGD Singapore Dollar THB Thailand Baht TND Tunisian Dinar TOP Tongan Pa anga USD US Dollar VUV Vanautu Vatu WST Samoan Tala XPF CFP Franc ZAR South African Rand . -

Currency Codes CRC Costa Rican Colon LY D Libyan Dinar SCR Seychelles Rupee

Global Wire is an available payment method for the currencies listed below. This list is subject to change at any time. Currency Codes CRC Costa Rican Colon LY D Libyan Dinar SCR Seychelles Rupee ALL Albanian Lek HRK Croatian Kuna LT L Lithuanian Litas SLL Sierra Leonean Leone DZD Algerian Dinar CZK Czech Koruna MKD/FYR Macedonia Denar SGD Singapore Dollar AMD Armenian Dram DKK Danish Krone MOP Macau Pataca SBD Solomon Islands Dollar AOA Angola Kwanza DJF Djibouti Franc MGA Madagascar Ariary ZAR South African Rand AUD Australian Dollar DOP Dominican Peso MWK Malawi Kwacha SSP South Sudanese Pound AWG Arubian Florin XCD Eastern Caribbean Dollar MVR Maldives Rufi yaa SRD Suriname Dollar AZN Azerbaijan Manat EGP Egyptian Pound MRU Mauritanian Olguiya SEK Swedish Krona BSD Bahamian Dollar EUR EMU Euro MUR Mauritius Rupee SZL Swaziland Lilangeni BHD Bahraini Dinar ERN Eritrea Nakfa MXN Mexican Peso CHF Swiss Franc BBD Barbados Dollar ETB Ethiopia Birr MDL Maldavian Lieu LKR Sri Lankan Rupee BYN Belarus Ruble FJ D Fiji Dollar MNT Mongolian Tugrik TWD Taiwan New Dollar BZD Belize Dollar GMD Gambian Dalasi MZN Mozambique Metical TJS Tajikistani Somoni BMD Bermudian Dollar GEL Georgian Larii MYR Malaysian Ringgit TZS Tanzanian Shilling BTN Bhutan Ngultram GTQ Guatemalan Quetzal MMK Burmese Kyat TOP Tongan Pa’anga BOB Bolivian Boliviano GNF Guinea Republic Franc NAD Namibian Dollar TTD Trinidad and Tobago Dollar BAM Bosnia & Herzagovina GYD Guyana Dollar ANG Netherlands Antillean Guilder TRY Turkish Lira BWP Botswana Pula HTG Haitian Gourde NPR Nepal Rupee TMT Turkmenistani Manat BRL Brazilian Real HNL Honduran Lempira NZD New Zealand Dollar AED U.A.E.