Seizing Opportunities for Canadians: India's Growth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Audio OTT Economy in India – Inflection Point February 2019 for Private Circulation Only

Audio OTT economy in India – Inflection point February 2019 For Private circulation only Audio OTT Economy in India – Inflection Point Contents Foreword by IMI 4 Foreword by Deloitte 5 Overview - Global recorded music industry 6 Overview - Indian recorded music industry 8 Flow of rights and revenue within the value chain 10 Overview of the audio OTT industry 16 Drivers of the audio OTT industry in India 20 Business models within the audio OTT industry 22 Audio OTT pie within digital revenues in India 26 Key trends emerging from the global recorded music market and their implications for the Indian recorded music market 28 US case study: Transition from physical to downloading to streaming 29 Latin America case study: Local artists going global 32 Diminishing boundaries of language and region 33 Parallels with K-pop 33 China case study: Curbing piracy to create large audio OTT entities 36 Investments & Valuations in audio OTT 40 Way forward for the Indian recorded music industry 42 Restricting Piracy 42 Audio OTT boosts the regional industry 43 Audio OTT audience moves towards paid streaming 44 Unlocking social media and blogs for music 45 Challenges faced by the Indian recorded music industry 46 Curbing piracy 46 Creating a free market 47 Glossary 48 Special Thanks 49 Acknowledgements 49 03 Audio OTT Economy in India – Inflection Point Foreword by IMI “All the world's a stage”– Shakespeare, • Global practices via free market also referenced in a song by Elvis Presley, economics, revenue distribution, then sounded like a utopian dream monitoring, and reducing the value gap until 'Despacito' took the world by with owners of content getting a fair storm. -

India's New Government and Implications for U.S. Interests

India’s New Government and Implications for U.S. Interests K. Alan Kronstadt Specialist in South Asian Affairs August 7, 2014 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R43679 India’s New Government and Implications for U.S. Interests Summary The United States and India have been pursuing a “strategic partnership” since 2004, and a 5th Strategic Dialogue session was held in New Delhi in late July 2014. A May 2014 national election seated a new Indian government led by the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and new Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Top U.S. officials express eagerness to engage India’s new leadership and re-energize what some see as a relationship flagging in recent years. High hopes for the engagement have become moderated as expectations held in both capitals remain unmet, in part due to a global economic downturn that has dampened commercial activity. Yet the two countries, estranged through the Cold War period, have now routinized cooperative efforts through myriad working groups on an array of bilateral and global issues. Prime Minister Modi is known as an able administrator, having overseen impressive economic development in 15 years as chief minister of India’s Gujarat state. But he also is a controversial figure for his Hindu nationalist views and for communal rioting that killed up to 2,000 people, most of them Muslims, in Gujarat in 2002. His BJP made history by becoming the first party to win an outright parliamentary majority in 30 years, meaning India’s federal government is no longer constrained by the vagaries of coalition politics. -

Personal Meaning Among Indocanadians and South Asians

Meaning and Satisfaction-India 1 Personal meaning among Indocanadians and South Asians Bonnie Kalkman, MA, 2003 Paul T. P. Wong, Ph.D. Meaning and Satisfaction-India 2 ABSTRACT This study extends Wong’s (1998) Personal Meaning Profile research on the sources and measurement of life meaning. An open-ended questionnaire was administered to an East Indian sample in India. From the 68 subjects ranging in age from 20 to 69, statements were gathered as to the possible sources of meaning in life. These statements were then analyzed according to their content and the 39 derived sources of meaning were added to Wong’s PMP to become the Modified PMP-India with a total of 96 items. In Study 2, the Modified PMP-India was then administered along with the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS; Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985) to East Indian subjects, 58 from India and 58 from Canada. When factor analysis was unsuccessful, content analysis was applied and this resulted in 10 factors: 1) Achievement, 2) Altruism and Self-Transcendence, 3) General Relationships, 4) Religion, 5) Intimate Relationships, 6) Affirmation of Meaning and Purpose in Life, 7) Morality, 8) Relationship with Nature, 9) Fair Treatment, and 10) Self-Acceptance. The Indo-Canadian subjects reported higher mean levels of life satisfaction, and higher mean levels for the factors: Intimate Relationships, General Relationships, Morality, and Fair Treatment. Females reported higher mean levels for the factors Intimate Relationships and Religion. Overall meaning correlated moderately with overall life satisfaction. Meaning and Satisfaction-India 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ………………………………………………………………… ii TABLE OF CONTENTS …………………………………………………. -

Research Report on Consumer Behaviour the We Ek

RESEARCH REPORT ON CONSUMER BEHAVIOUR THE WE EK Journalism with a human touch Submitted To: - Submitted By: - Declaration The project report entitled is submitted to in partial fulfillment of “post graduate diploma in management”. The report is exclusively and comprehensively prepared and conceptualized by me. All the information and data given here in this project is as per my fullest knowledge collected during my studies and from the various websites. The report is an original work done by me and it has not formed the basis for the award of any other degree or diploma elsewhere. Place : LUCKNOW AJAY SINGH Date : ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The project report is a result of our rigorous and devoted effort and valuable guidance of Mr.sanjeev Sharma, Mr.Sandeep and it is the result of the traning in malayala manorama, it contains brief history of the organization and its mission / objectives. Malayala manorama is a well known name for its valuable services. The organization is maintaining the quality of the services throughout. I have done my project in malayala manorama, Lucknow. The focus of the project is overview of the various aspects of services basically in Consumer Buying behavior. This project as a summer traning is a partial fulfillment of two year MBA course. In this project we have strived to include all the details regarding the subject and made a sincere effort towards completion of the same. In this course of training we learned various pratical aspects about the Consumer Buying Behaviour and we knew about the major benefits provided by malayala manorama to their consumers & to the society. -

India Today Rankings

SPECIAL ISSUE 25TH ANNUAL SURVEY www.indiatoday.in JULY 5, 2021 `75 THE BEST COLLEGES OF INDIA The Comprehensive inDiA ToDAY-mDrA GUi De To eXCeLLenCe ACross 14 m AJor DisC ipLines BEST COLLEGES 25YEARS DENTAL RANKS & SCORES OF COLLEGES ENGINEERING (GOVERNMENT) RANKS & SCORES OF COLLEGES OVER- OVERALL COLLEGE & CITY GOVT/ INTAKE ACADEMIC INFRASTRUC- PERSONALITY CAREER OBJECTIVE PERCEPTU- OVERALL OVER- OVERALL COLLEGE AND CITY INTAKE ACADEMIC INFRASTRUC- PERSONALITY CAREER OBJECTIVE PERCEPTU- OVERALL ALL RANK PVT QUALITY & EXCELLENCE TURE & LIVING & LEADERSHIP PROGRESSION SCORE AL SCORE SCORE ALL RANK QUALITY & EXCELLENCE TURE & LIVING & LEADERSHIP PROGRESSION SCORE AL SCORE SCORE RANK 2020 (G/ P) GOVERNANCE EXPERIENCE DEVELOPMENT & PLACEMENT RANK 2020 GOVERNANCE EXPERIENCE DEVELOPMENT & PLACEMENT 2021 2021 300 300 240 180 180 1,200 800 2,000 288 264 240 120 288 1,200 800 2,000 - 50 NP INSTITUTE OF DENTAL SCIENCES, SIKSHA ‘O’ P 115.3 190.3 167.1 106.9 67.8 647.4 150.2 797.6 14 16 INDIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, GANDHINAGAR 210.6 210.8 209.2 97.3 171.1 899 706.3 1,605.3 ANUSANDHAN (DEEMED TO BE UNIVERSITY), 15 17 COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING, PUNE 205.7 170.6 189.5 87.3 186.8 839.9 739.7 1,579.6 BHUBANESWAR 16 18 VISVESVARAYA NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, NAGPUR 210.8 165.5 203.1 88.2 204 871.6 706.4 1,578 - 51 NP INDERPRASTHA DENTAL COLLEGE & HOSPITAL, P 139.2 156.0 117.6 147.5 109.8 670.1 118.0 788.1 GHAZIABAD - 17 NP MALAVIYA NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, JAIPUR 208.4 195.3 178.7 88.6 191.9 862.9 713 1,575.9 - 52 NP KAMINENI INSTITUTE -

Two-Line Headline Goes Here

2014 *PLEASE NOTE: The Topline findings are not for any business/commercial use. Divergence from this will have legal implications. THE INDIAN CONSUMER INDIA DEMOGRAPHICS Education* 63.3 63.6 2013 26.8 26.6 2014 9.9 9.8 2672 Lakh Households Illiterate Not a Graduate Graduate & above 9624 Lakh 12+ Individuals Age Distribution* 23.4 23.4 21.6 21.5 18.8 18.8 14.8 14.8 11.1 11.1 10.3 10.3 2013 2014 12 to 15 16 to 19 20 to 29 30 to 39 40 to 49 50+ Individual Universe Estimated to March 2014 * Individuals 12+, Base (000s) – 9,62,389 2014 STEADY GROWTH IN AFFLUENCE National Consumer Classification System 13.9 13.8 13.6 13.6 12.5 12.6 10 10.2 9.6 9.9 9.6 9.1 7.9 7.6 2013 6.5 6.2 6.3 6.3 2014 4.7 4.2 4.2 4.3 1.7 1.8 A1 A2 A3 B1 B2 C1 C2 D1 D2 E1 E2 E3 Household Universe estimated to March 2014 Base (000s) – 267,622 2014 LOW PENETRATION: AN OPPORTUNITY Durable Ownership Consumer Products’ Purchase All India All India Two Wheeler 24% Purchase Incidence Products Among Households Refrigerator 22% Edible Oil, Sugar, Tea, Toothpaste, Fabric Washing (Powders / 75 – 100% Washing Machine 9% Liquids), Fabric Washing (Cakes / Bars) PC / Laptop 9% 50 – 74% Agarbatti, Biscuits Car 5% 25 – 49% Utensil Cleaners, Toilet Cleaners Air Conditioner 2% Coffee, Floor Cleaners, Milk Powder / Dairy Whiteners, Microwave Oven 2% 1 – 24% Ketchup / Sauces, Honey, Chyawanprash, Cheese / Cheese Products Base (000s) – 267,622 All Households 2014 MEDIA CONSUMPTION MEDIA CONSUMPTION ANY MEDIA 677,435 (+21,184) 301,570 621,118 98,967 58,518 77,939 (+19,740) (+18,498) (+15,287) -

Canadian Companies That Do Business in India

APRIL 2015 CANADIAN COMPANIES THAT DO BUSINESS IN INDIA: NEW LANDSCAPES, NEW PLAYERS AND THE OUTLOOK FOR CANADA THE ASIA PACIFIC FOUNDATION OF CANADA WOULD LIKE TO THANK THE FOLLOWING PARTNERS FOR THEIR GENEROUS SUPPORT OF THIS PROJECT. LEAD PARTNER PARTNERS 2 ASIA PACIFIC FOUNDATION OF CANADA - FONDATION ASIE PACIFIQUE DU CANADA CANADIAN COMPANIES THAT DO BUSINESS IN INDIA CANADIAN COMPANIES THAT DO BUSINESS IN INDIA: NEW LANDSCAPES, NEW PLAYERS AND THE OUTLOOK FOR CANADA Douglas Goold Douglas Goold is a research consultant (India) with the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada, PARTNERS and was recently director of APF Canada’s National Conversation on Asia and senior editor. He was previously president and CEO of the Canadian Institute of International Affairs/Canadian International Council, and is a noted author, journalist and commentator. He was co-author, with Andrew Willis, of The Bre-X Fraud, a national number-one bestseller, and a national columnist for The Globe and Mail as well as editor of Report on Business and Report on Business Magazine. He received his PhD from Cambridge University and is the recipient of two Killam Postdoctoral Fellowships. CANADIAN COMPANIES THAT DO BUSINESS IN INDIA: NEW LANDSCAPES, NEW PLAYERS AND THE OUTLOOK FOR CANADA 3 Gate of India in New Delhi 4 ASIA PACIFIC FOUNDATION OF CANADA - FONDATION ASIE PACIFIQUE DU CANADA TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword ————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————— 6 Executive Summary ——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————— 10 Acknowledgements -

Report Covers Simon7

Leveraging Australia’s Indian diaspora for deeper bilateral trade and investment relations with India SURJEET DOGRA DHANJI HARIPRIYA RANGAN January 2018 LEVERAGING AUSTRALIA’S INDIAN DIASPORA FOR DEEPER BILATERAL TRADE AND INVESTMENT RELATIONS WITH INDIA A commissioned study contributing to A Report to the Australian Government by Mr Peter N Varghese AO ‘An India Economic Strategy to 2035: Navigating from Potential to Delivery’ Suggested Citation Dhanji, SD, and Rangan, H (2018) ‘Leveraging Australia’s Indian diaspora for deeper bilateral trade and investment relations with India.’ January. Melbourne: Australia India Institute. Note The views expressed in this study are of the authors, and do not reflect the views of the Australia India Institute, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, or Mr Peter M. Varghese, AO. Executive Summary This study is guided by two questions: How can the Indian diaspora in Australia be mobilised as an asset for building deeper bilateral trade and investment relations with India? What are the institutional frameworks and industry linkages that require facilitation by the Australian government to enable its Indian diaspora to build dynamic and productive bilateral economic relations with India? The study adopts a comparative approach to answer these questions, looking first at the Indian government’s engagement with its global diaspora, and then at the role played by the Indian diaspora in USA, Canada, the UK and Singapore in building trade and investment links between these countries and India. For each country case, the study provides an overview of its Indian diaspora population and their participation in the economy; their remittances and investments in India; attracting investments from India; and their organisations promoting stronger economic and political relations with India. -

Contemporary Dance in India Today a Survey

CONTEMPORARY DANCE IN INDIA TODAY A SURVEY Annette Leday With the support of the Centre National de la Danse, Paris (Aide à la recherche et au patrimoine en danse) Translation from the French commissioned by India Foundation for the Arts and Association Keli-Paris 2019 Anita Ratnam (Chennai): "In India the word 'contemporary' applies to anyone who wants to move away from their guru or from the tradition they have learned, to experiment and explore." Mandeep Raikhy (Delhi): "We have rejected the term 'contemporary' and we are still looking for an alternative term." Vikram Iyengar (Kolkata): "I think the various layers of what constitutes "contemporary" in Indian dance have not yet been defined." CONTENTS PREFACE 1 1. INTRODUCTION 4 2. SOME HISTORICAL MARKERS 5 a) Mystifications 5 b) The pioneers of modern dance 7 3. SOME GEOGRAPHIC MARKERS 10 4. A TYPOLOGY OF CONTEMPORARY DANCE IN INDIA 13 a) The 'Neo-Classics' 13 b) Towards radicality 17 c) A suspended space 19 d) Shunning the classics 21 e) Between dance and theatre 22 f) The Bollywood phenomenon 23 g) Commercial contemporaries 25 5. THEMES 26 a) The nurturing techniques 27 b) The issue of Indian identity 28 c) Themes of yesterday and of today 29 d) Dance and politics 30 6. THE CREATIVE PROCESS 33 7. PRESS, CRITIQUE AND FORUMS 35 8. TEACHING AND TRANSMISSION 37 9. VENUES AND FUNDING 41 a) Places of performance 41 b) Festivals 43 c) Working places 45 d) Funding 47 e) Opportunities 48 10. INTERNATIONAL CONTACTS 49 11. PERSPECTIVES 54 12. CONCLUSION 56 PREFACE After a decade immersed in the Kathakali of Kerala, I engaged in a dynamic of contemporary choreography inspired by this great performing tradition. -

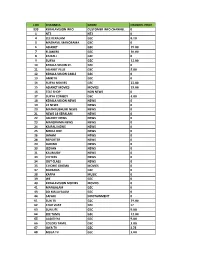

List of Pay Channels

List of Pay Channels SL# CHANNEL NAMES SD/HD LANGUAGE GENRE BROADCASTER NAME DRP 1 & FLIX SD ENGLISH MOVIES ZEE 15.00 2 & FLIX HD HD ENGLISH MOVIES ZEE 19.00 3 & PICTURES SD HINDI MOVIES ZEE 10.00 4 & PRIVE HD HD ENGLISH MOVIES ZEE 19.00 5 & TV SD HINDI GEC ZEE 12.00 6 24 GHANTA SD BENGALI GEC ZEE 0.10 7 AAJ TAK SD HINDI NEWS TV TODAY 0.75 8 ADITHYA TV SD TAMIL MOVIES SUN 9.00 9 ANIMAL PLANET SD ENGLISH INFO & LIFESTYLE DISCOVERY 2.00 10 ANIMAL PLANET HD HD ENGLISH INFO & LIFESTYLE DISCOVERY 3.00 11 ASIANET SD MALAYALAM GEC STAR 19.00 12 ASIANET HD HD MALAYALAM GEC STAR 19.00 13 ASIANET MOVIES SD MALAYALAM MOVIES STAR 15.00 14 ASIANET PLUS SD MALAYALAM GEC STAR 5.00 15 AXN SD ENGLISH GEC SONY 5.00 16 AXN HD HD ENGLISH GEC SONY 7.00 17 BBC WORLD SD ENGLISH NEWS BBC 1.00 18 BINDASS SD HINDI GEC DISNEY 1.00 19 CARTOON NETWORK SD ENGLISH KIDS TURNER 4.25 20 CHINTU TV SD KANNADA KIDS SUN 6.00 21 CHUTTI TV SD TAMIL KIDS SUN 6.00 22 CNBC AWAAZ SD HINDI NEWS TV18 1.00 23 CNBC TV18 SD ENGLISH NEWS TV18 4.00 24 CNBC TV18 HD HD ENGLISH NEWS TV18 1.00 25 CNN SD ENGLISH NEWS TURNER 0.50 26 CNN NEWS18 SD ENGLISH NEWS TV18 0.50 27 COLORS SD HINDI GEC TV18 19.00 28 COLORS BANGLA SD BENGALI GEC TV18 7.00 29 COLORS BANGLA HD HD BENGALI GEC TV18 14.00 30 COLORS GUJRATHI SD GUJARATI GEC TV18 5.00 31 COLORS INFINITY SD ENGLISH GEC TV18 7.00 32 COLORS INFINITY HD HD ENGLISH GEC TV18 9.00 33 COLORS KANNADA SD KANNADA GEC TV18 19.00 34 COLORS KANNADA CINEMA SD KANNADA MOVIES TV18 2.00 35 COLORS KANNADA HD HD KANNADA GEC TV18 19.00 36 COLORS MARATHI SD MARATHI -

FULL-CHANNEL-LIST.Pdf

LCN CHANNELS GENRE CHANNEL PRICE 999 KERALAVISION INFO CUSTOMER INFO CHANNEL 0 1 NT3 NT3 0 4 ZEE KERALAM GEC 0.10 5 MAZHAVIL MANORAMA GEC 0 6 ASIANET GEC 19.00 7 FLOWERS GEC 10.00 8 KAIRALI GEC 0 9 SURYA GEC 12.00 10 KERALA VISION ST. GEC 0 11 ASIANET PLUS GEC 5.00 12 KERALA VISION CABLE GEC 0 13 AMRITA GEC 0 14 SURYA MOVIES GEC 11.00 15 ASIANET MOVIES MOVIES 15.00 16 TELE SHOP NON NEWS 0 17 SURYA COMEDY GEC 4.00 18 KERALA VISION NEWS NEWS 0 19 24 NEWS NEWS 0 20 MATHRUBHUMI NEWS NEWS 0 21 NEWS 18 KERALAM NEWS 0 22 ASIANET NEWS NEWS 0 23 MANORAMA NEWS NEWS 0 24 KAIRALI NEWS NEWS 0 25 MEDIA ONE NEWS 0 26 JANAM NEWS 0 28 REPORTER NEWS 0 29 JAIHIND NEWS 0 30 JEEVAN NEWS 0 31 KAUMUDY NEWS 0 33 VICTERS NEWS 0 34 OUT CLASS NEWS 0 35 C HOME CINEMA MOVIES 0 37 DARSANA GEC 0 38 KAPPA MUSIC 0 39 WE GEC 0 40 KERALAVISION MOVIES MOVIES 0 41 MANGALAM GEC 0 43 DD MALAYALAM GEC 0 44 SAFARI INFOTAINMENT 0 61 SUN TV GEC 19.00 62 STAR VIJAY GEC 17 63 SUN LIFE GEC 9.00 64 ZEE TAMIL GEC 12.00 65 AADITHYA GEC 9.00 66 COLORS TAMIL GEC 3.00 67 JAYA TV GEC 3.78 68 MEGA TV GEC 3.00 69 RAJ TV GEC 3.00 70 DD PODIGAI GEC 0 71 KALAIGNAR TV GEC 0 73 PUTHUYUGAM NON NEWS 0 74 MAKKAL TV NEWS 0 75 MK TV 6 NON NEWS 0 76 VASANTH TV NEWS 0 77 CAPTAIN TV NEWS 0 78 VANAVIL NON NEWS 0 79 POLIMER NEWS 0 82 KALAIGNAR MURASU NON NEWS 0 83 MK TV MUSIC 0 85 KALINGER SIRIPPOLI NON NEWS 0 87 PEPPERS NON NEWS 0 90 VEDHAR NEWS 0 91 VIJAY SUPER GEC 2.00 92 K TV GEC 19.00 93 MEGA 24 GEC 1.00 94 JAYA MOVIES MOVIES 0 95 MALAR TV NON NEWS 0 96 MEENAKSHI TV NON NEWS 0 97 ZEE THIRAI GEC 0 100 -

India Mumbai Lawrence Liang and Ravi Sundaram Contributors: Prashant Iyengar, Siddarth Chaddha, Nupur Jain, Chennai Jinying Li, and Akbar Zaidi Bangalore

Delhi SOCIAL SCIENCE RESEARCH COUNCIL • MEDIA PIRACY IN EMERGING ECONOMIES SOCIAL SCIENCE RESEARCHCHAPTER COUNCIL THREE • MEDIA • SOUTH PIRACY AFRICA IN EMERGING ECONOMIES Karachi Chapter 8: India Mumbai Lawrence Liang and Ravi Sundaram Contributors: Prashant Iyengar, Siddarth Chaddha, Nupur Jain, Chennai Jinying Li, and Akbar Zaidi Bangalore Introduction Piracy entered public consciousness in India in the context of globalization in the 1980s. The rapid spread of video culture, the image of India as an emerging software giant, and the measurement of comparative advantage between nations in terms of the knowledge economy pushed questions about the control of knowledge and creativity—about “intellectual property”—into the foreground of economic policy debates. The consolidation of Indian media industries with global ambitions in film, music, and television gave the protection of copyright, especially, a new perceived urgency. Large-scale piracy—at the time still primarily confined to audio cassettes and books sold on the street—began to be seen as a threat not just to specific businesses but to larger economic models and national ambitions. The “problem” of intellectual property (IP) protection in India—in terms of both the laws on the books and enforcement practices on the streets—took shape through this conversation between lawyers, judges, government ministers, and media lobbyists. The high-level policy dialogue has produced several important revisions to Indian copyright law, including amendments to the Copyright Act in 1994 and 1999 to address the growth of cassette and optical disc piracy, respectively. A new round of proposals, reflecting a more recent array of battles over the control of cultural goods, began to emerge in 2006 and will probably be voted on in early 2011.