Moving Towards an Open Defecation Free City: the Journey of Satara

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prominent Personalities

Prominent Personalities Yeshawantrao Chavan The freedom fighter, leader of 'Sanyukt Maharashtra Movement' and the first Chief Minister of Maharashtra, Yeshwantrao Balwantrao Chavan born at Devrashtre, Tal.Karad dist.Satara. Several times he represented Satara Parliamentary Constituency. Besides the politics he also wrote 'Krishna kath' and several other books. This soft hearted leader honored with several important responsibilities for country like Home Minister, Defense Minister and Dy.Prime Minister. He introduced 'Panchayat Raj' system for the first time. Yeshwantrao Chavan Dr. Karmaveer Bhaurao Patil The greatest educationalist and founder of 'Rayat Shikshan Sanstha' the dedicated largest educational institute in the state. He has honored by D.Lit. from Pune University on 5/4/1959. His work particularly for poor and backward class students through establishing hostels is the landmark in Maharashtra. He was related with several social and co-operative movements. Also took active part in freedom struggle. The head quarter of 'Rayat Shikshan Sanstha' is at Satara with 689 branches through out state and more than 4.42 lacks students taking education in several branches. Dr. Karmveer Bhaurao Patil Rajmata Sumitraraje Bhosale The daughter-in-law of Shrimant Chhatrapati Rajaram Maharaj (Abasaheb), the successor of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, 'Kulavadhu' Rajmata Sumitraraje Bhosale was respectable personality in the district. She was related with several social and co-operative movements. She was founder member of several institutes. The softhearted 'Rajmata' was died on 05/06/1999. Rajmata Sumitraraje Bhosale Khashaba Jadhav (15'th Jan. 1926 - 14 Aug. 1984) Born in very poor farmer family at Goleshwar Tal. Karad, the only Olympic Medal Winner for India till 2000. -

Sources of Maratha History: Indian Sources

1 SOURCES OF MARATHA HISTORY: INDIAN SOURCES Unit Structure : 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Maratha Sources 1.3 Sanskrit Sources 1.4 Hindi Sources 1.5 Persian Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Additional Readings 1.8 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES After the completion of study of this unit the student will be able to:- 1. Understand the Marathi sources of the history of Marathas. 2. Explain the matter written in all Bakhars ranging from Sabhasad Bakhar to Tanjore Bakhar. 3. Know Shakavalies as a source of Maratha history. 4. Comprehend official files and diaries as source of Maratha history. 5. Understand the Sanskrit sources of the Maratha history. 6. Explain the Hindi sources of Maratha history. 7. Know the Persian sources of Maratha history. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The history of Marathas can be best studied with the help of first hand source material like Bakhars, State papers, court Histories, Chronicles and accounts of contemporary travelers, who came to India and made observations of Maharashtra during the period of Marathas. The Maratha scholars and historians had worked hard to construct the history of the land and people of Maharashtra. Among such scholars people like Kashinath Sane, Rajwade, Khare and Parasnis were well known luminaries in this field of history writing of Maratha. Kashinath Sane published a mass of original material like Bakhars, Sanads, letters and other state papers in his journal Kavyetihas Samgraha for more eleven years during the nineteenth century. There is much more them contribution of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhan Mandal, Pune to this regard. -

Satara. in 1960, the North Satara Reverted to Its Original Name Satara, and South Satara Was Designated As Sangli District

MAHARASHTRA STATE GAZETTEERS Government of Maharashtra SATARA DISTRICT (REVISED EDITION) BOMBAY DIRECTORATE OF GOVERNMENT PRINTING, STATIONARY AND PUBLICATION, MAHARASHTRA STATE 1963 Contents PROLOGUE I am very glad to bring out the e-Book Edition (CD version) of the Satara District Gazetteer published by the Gazetteers Department. This CD version is a part of a scheme of preparing compact discs of earlier published District Gazetteers. Satara District Gazetteer was published in 1963. It contains authentic and useful information on several aspects of the district and is considered to be of great value to administrators, scholars and general readers. The copies of this edition are now out of stock. Considering its utility, therefore, need was felt to preserve this treasure of knowledge. In this age of modernization, information and technology have become key words. To keep pace with the changing need of hour, I have decided to bring out CD version of this edition with little statistical supplementary and some photographs. It is also made available on the website of the state government www.maharashtra.gov.in. I am sure, scholars and studious persons across the world will find this CD immensely beneficial. I am thankful to the Honourable Minister, Shri. Ashokrao Chavan (Industries and Mines, Cultural Affairs and Protocol), and the Minister of State, Shri. Rana Jagjitsinh Patil (Agriculture, Industries and Cultural Affairs), Shri. Bhushan Gagrani (Secretary, Cultural Affairs), Government of Maharashtra for being constant source of inspiration. Place: Mumbai DR. ARUNCHANDRA S. PATHAK Date :25th December, 2006 Executive Editor and Secretary Contents PREFACE THE GAZETTEER of the Bombay Presidency was originally compiled between 1874 and 1884, though the actual publication of the volumes was spread over a period of 27 years. -

Final ROUTE DETAILS

th 6 Edition - Route Details The Route The Race starts in Pune, the city of cycles, and finishes in Goa, on the sea shore. Set on the Deccan Plateau, the route follows the Sahyadri Range, which defines the western edge of the Deccan, finally dropping through dense forests that cover the cliffs of the Escarpment, into the Konkan as it heads to the Indian Ocean. Each year the route is modified to adjust to road conditions. This year the route goes via Surur phata through Wai to Panchagani, turning south to go through Bhilar towards Medha/Satara. From Satara till Belur (just before Dharwad it remains on the NH4, turning back to Belgaum to head for Goa through Chorla Ghat. Route Details have been finalized after a physical inspection of road conditions conducted by the team in end of October. We do not expect any further changes, except if there are any extenuating circumstances. If there are any last minute changes, participants will be notified. Description / Cautions The Start Venue for this edition is The Cliff Restaurant and Club, at Forest Trails Bhugaon, Paranjape Schemes (Construction) Ltd which has hosted the start of the last 2 editions. From there one heads steeply downhill and on to Chandni chowk to join NH4, heading south towards Bangalore. The first climb to Katraj tunnel is followed by a flat, slight downhill until one crosses the Nira River at Shirwal at @60 km. While this stretch usually offers an opportunity to do very good time, this year there are some sections under construction and participants are cautioned that the service roads that one has to take, are in bad condition. -

List of Nagar Panchayat in the State of Maharashtra Sr

List of Nagar Panchayat in the state of Maharashtra Sr. No. Region Sub Region District Name of ULB Class 1 Nashik SRO A'Nagar Ahmednagar Karjat Nagar panchayat NP 2 Nashik SRO A'Nagar Ahmednagar Parner Nagar Panchayat NP 3 Nashik SRO A'Nagar Ahmednagar Shirdi Nagar Panchyat NP 4 Nashik SRO A'Nagar Ahmednagar Akole Nagar Panchayat NP 5 Nashik SRO A'Nagar Ahmednagar Newasa Nagarpanchayat NP 6 Amravati SRO Akola Akola Barshitakli Nagar Panchayat NP 7 Amravati SRO Amravati 1 Amravati Teosa Nagar Panchayat NP 8 Amravati SRO Amravati 1 Amravati Dharni Nagar Panchayat NP 9 Amravati SRO Amravati 1 Amravati Nandgaon (K) Nagar Panchyat NP 10 Aurangabad S.R.O.Aurangabad Aurangabad Phulambri Nagar Panchayat NP 11 Aurangabad S.R.O.Aurangabad Aurangabad Soigaon Nagar Panchayat NP 12 Aurangabad S.R.O.Jalna Beed Ashti Nagar Panchayat NP 13 Aurangabad S.R.O.Jalna Beed Wadwani Nagar Panchayat NP 14 Aurangabad S.R.O.Jalna Beed shirur Kasar Nagar Panchayat NP 15 Aurangabad S.R.O.Jalna Beed Keij Nagar Panchayat NP 16 Aurangabad S.R.O.Jalna Beed Patoda Nagar Panchayat NP 17 Nagpur SRO Nagpur Bhandara Mohadi Nagar Panchayat NP 18 Nagpur SRO Nagpur Bhandara Lakhani nagar Panchayat NP 19 Nagpur SRO Nagpur Bhandara Lakhandur Nagar Panchayat NP 20 Amravati SRO Akola Buldhana Sangrampur Nagar Panchayat NP 21 Amravati SRO Akola Buldhana Motala Nagar panchyat NP 22 Chandrapur SRO Chandrapur Chandrapur Saoli Nagar panchayat NP 23 Chandrapur SRO Chandrapur Chandrapur Pombhurna Nagar panchayat NP 24 Chandrapur SRO Chandrapur Chandrapur Korpana Nagar panchayat NP 25 Chandrapur -

Mahableshwar Panchgani

MAHABLESHWAR PANCHGANI MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT AND FORESTS NOTIFICATION NEW DELHI, 17th January, 2001 S.O 52(E).– Whereas a notification under sub section (1) and clause (v) of sub section (2) of Section 3 of the Environment Protection Act, 1986, inviting objection or suggestion against the notification notifying the Mahableshwar Panchgani as an Eco sensitive region and imposing restriction on industries, operations, processes and other developmental activities in the region which have detrimental effect on the environment was published in S.O. No. 693(E) dated the 25th July, 2000; And whereas all objections or/and suggestions received have been duly considered by the Central Government Now, therefore, in exercise of the powers conferred by clause (d) of sub-rule (3) of rule 5 of the Environment (Protection) Rules, 1986, and all other powers vesting in its behalf, the Central Government hereby notify the Mahableshwar Panchgani Region (as defined in the Government of Maharashtra notification of 29th April, 1983 as an Eco Sensitive Zone. (Copy attached as Annexure). The Region shall include the entire area within the boundaries of the Mahableshwar Tehsil and the villages of Bondarwadi, Bhuteghar, Danwali, Taloshi and Umbri of Jaoli Tehsil of the Satara District in the Maharashtra state. 1. All activities in the forests (both within and outside municipal areas) shall be governed by the provisions of the Indian Forests Act, 1927 (16 of 1927) and Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980 (69 of 1980). All activities in the sanctuaries and national parks shall be governed by the provisions of the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972 (53 of 1972). -

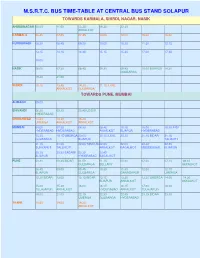

M.S.R.T.C. Bus Time-Table at Central Bus Stand Solapur

M.S.R.T.C. BUS TIME-TABLE AT CENTRAL BUS STAND SOLAPUR TOWARDS KARMALA, SHIRDI, NAGAR, NASIK AHMEDNAGAR 08.00 11.00 13.25 16.30 22.30 AKKALKOT KARMALA 06.45 07.00 07.45 10.00 12.00 15.30 16.00 KURDUWADI 08.30 08.45 09.20 10.00 10.30 11.30 12.15 13.15 14.15 14.45 15.15 15.30 17.00 17.45 18.00 NASIK 06.00 07.30 08.45 09.30 09.45 10.00 BIJAPUR 14.30 GULBARGA 19.30 21.00 SHIRDI 10.15 13.45 14.30 21.15 ILKAL AKKALKOT GULBARGA TOWARDS PUNE, MUMBAI ALIBAGH 09.00 BHIVANDI 06.30 09.30 20.45 UDGIR HYDERABAD CHINCHWAD 13.30 14.30 15.30 UMERGA AKKALKOT AKKALKOT MUMBAI 04.00 07.30 08.30 08.45 10.15 15.00 15.30 INDI HYDERABAD HYDERABAD AKKALKOT BIJAPUR HYDERABAD 15.30 19.15 UMERGA 20.00 20.15 ILKAL 20.30 21.15 BIDAR 21.15 GULBARGA BIJAPUR TALIKOTI 21.15 21.30 22.00 TANDUR 22.00 22.00 22.30 22.45 SURYAPET TALLIKOTI AKKALKOT BAGALKOT MUDDEBIHAL BIJAPUR 23.15 23.30 BADAMI 23.30 23.45 BIJAPUR HYDERABAD BAGALKOT PUNE 00.30 00.45 BIDAR 01.00 01.15 05.30 07.00 07.15 08.15 GULBARGA BELLARY AKKALKOT 08.45 09.00 09.45 10.30 11.30 12.00 12.15 BIJAPUR GULBARGA GANAGAPUR UMERGA 12.30 BIDAR 13.00 13.15 BIDAR 13.15 13.30 13.30 UMERGA 14.00 14.30 BIJAPUR AKKALKOT AKKALKOT 15.00 15.30 16.00 16.15 16.15 17.00 18.00 TULAJAPUR AKKALKOT HYDERABAD AKKALKOT TULAJAPUR 19.00 21.00 22.15 22.30 22.45 23.15 BIDAR 23.30 UMERGA GULBARGA HYDERABAD THANE 10.45 19.00 19.30 AKKALKOT TOWARDS AKKALKOT, GANAGAPUR, GULBARGA AKKALKOT 04.15 05.45 06.00 08.15 09.15 09.15 10.30 10.45 11.00 11.30 11.45 12.15 13.45 14.15 15.30 16.00 16.30 16.45 17.00 GULBARGA 02.00 PUNE 05.15 06.15 07.30 08.15 -

Responsible for Plague in Bombay Province, Though They Have Been

Bull. Org. mond. Sante Bull. World Hlth Org.J 1951, 4, 75-109 SPREAD OF PLAGUE IN THE SOUTHERN AND CENTRAL DIVISIONS OF BOMBAY PROVINCE AND PLAGUE ENDEMIC CENTRES IN THE INDO-PAKISTAN SUBCONTINENT a M. SHARIF, D.Sc., Ph.D., F.N.I. Formerly Assistant Director in Charge of Department of Entomology, Haffkine Institute, Bombay b Manuscript received in September 1949 The findings of the Plague Recrudescence Inquiry in Sholapur and Adjoining Districts, conducted by Sharif & Narasimham11 12 in the districts of Sholapur and Dharwar during 1940 to 1943, do not support the idea that wild rodents help to carry plague infection from one place to another as in " temperate climes ".4 Wild rodents cannot be considered responsible for plague in Bombay Province, though they have been shown to be so in Transbaikalia, Mongolia, South-Eastern Russia, South Africa, and the western parts of the USA.17 In Bombay Province, the domestic rat perpetuates the plague infection. In some suitable places the infection among domestic rats goes on throughout the year. The infection is not apparent during the hot and dry season, its intensity being diminished because of the ill effect of prevailing climatic conditions on the wanderings of adult rat-fleas ; it pursues the course of a slow subterranean enzootic from burrow to burrow. The conclusion of the off-season is characterized by the advent of the rainy season, which exerts its influence in two ways first, it causes the rats from outside shelters to herd into burrows indoors and remain there perforce, which results in a considerable increase in the rat population within houses; secondly, it brings down the temperature and increases the humidity to such an extent as to result in a striking rise in the flea population and to allow rat-fleas to come out of burrows to attack human beings. -

Satara District Maharashtra

1798/DBR/2013 भारत सरकार जल संसाधन मंत्रालय कᴂ द्रीय भूजल बो셍ड GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD महाराष्ट्र रा煍य के अंत셍डत सातारा जजले की भूजल विज्ञान जानकारी GROUND WATER INFORMATION SATARA DISTRICT MAHARASHTRA By 饍िारा Abhay Nivasarkar अभय ननिसरकर Scientist-B िैज्ञाननक - ख म鵍य क्षेत्र, ना셍पुर CENTRAL REGION, NAGPUR 2013 1 SATARA DISTRICT AT A GLANCE 1. LOCATION North latitude : 17°05’ to 18°11’ East longitude : 73°33’ to 74°54’ Normal Rainfall : 473 -6209 mm 2. GENERAL FEATURES Geographical area : 10480 sq.km. Administrative division : Talukas – 11 ; Satara , Mahabeleshwar (As on 31.3.2013) Wai, Khandala, Phaltan, Man,Jatav, Koregaon Jaoli, , Patan, Karad. Towns : 10 Villages : 1721 Watersheds : 52 3. POPULATION (2001, 2010 Census) : 28.09,000., 3003922 Male : 14.08,000, 1512524 Female : 14.01,000, 1491398 Population growth (1991-2001) : 14.59, 6.94 % Population density : 268 , 287 souls/sq.km. Literacy : 78.22 % Sex ratio : 995 (2010 Census) Normal annual rainfall : 473 mm 6209 mm (2001-2010) 4 GEOMORPHOLOGY Major Geomorphic Unit : Western Ghat, Foothill zone , Central , : Plateau and eastern plains Major Drainage : Krishna, Nira, Man 5 LAND USE (2010) Forest area : 1346 sq km Net Sown area : 6960 sq km Cultivable area : 7990 sq km 6 SOIL TYPE : 2 Medium black, Deep black 7 PRINCIPAL CROPS Jawar : 2101 sq km Bajara : 899 sq km Cereals : 942 sq km Oil seeds : 886 sq km Sugarcane : 470 sq km 8 GROUND WATERMONITORING Dugwell : 46 Piezometer : 06 9 GEOLOGY Recent : Alluvium i Upper-Cretaceous to -

4. Maharashtra Before the Times of Shivaji Maharaj

The Coordination Committee formed by GR No. Abhyas - 2116/(Pra.Kra.43/16) SD - 4 Dated 25.4.2016 has given approval to prescribe this textbook in its meeting held on 3.3.2017 HISTORY AND CIVICS STANDARD SEVEN Maharashtra State Bureau of Textbook Production and Curriculum Research, Pune - 411 004. First Edition : 2017 © Maharashtra State Bureau of Textbook Production and Curriculum Research, Reprint : September 2020 Pune - 411 004. The Maharashtra State Bureau of Textbook Production and Curriculum Research reserves all rights relating to the book. No part of this book should be reproduced without the written permission of the Director, Maharashtra State Bureau of Textbook Production and Curriculum Research, ‘Balbharati’, Senapati Bapat Marg, Pune 411004. History Subject Committee : Cartographer : Dr Sadanand More, Chairman Shri. Ravikiran Jadhav Shri. Mohan Shete, Member Coordination : Shri. Pandurang Balkawade, Member Mogal Jadhav Dr Abhiram Dixit, Member Special Officer, History and Civics Shri. Bapusaheb Shinde, Member Varsha Sarode Shri. Balkrishna Chopde, Member Subject Assistant, History and Civics Shri. Prashant Sarudkar, Member Shri. Mogal Jadhav, Member-Secretary Translation : Shri. Aniruddha Chitnis Civics Subject Committee : Shri. Sushrut Kulkarni Dr Shrikant Paranjape, Chairman Smt. Aarti Khatu Prof. Sadhana Kulkarni, Member Scrutiny : Dr Mohan Kashikar, Member Dr Ganesh Raut Shri. Vaijnath Kale, Member Prof. Sadhana Kulkarni Shri. Mogal Jadhav, Member-Secretary Coordination : Dhanavanti Hardikar History and Civics Study Group : Academic Secretary for Languages Shri. Rahul Prabhu Dr Raosaheb Shelke Shri. Sanjay Vazarekar Shri. Mariba Chandanshive Santosh J. Pawar Assistant Special Officer, English Shri. Subhash Rathod Shri. Santosh Shinde Smt Sunita Dalvi Dr Satish Chaple Typesetting : Dr Shivani Limaye Shri. -

Pedostibes Tuberculosus) at the Koyna Wildlife Sanctuary, Satara District, Maharashtra, India (Elevation 921.5 M)

WWW.IRCF.ORG/REPTILESANDAMPHIBIANSJOURNALTABLE OF CONTENTS IRCF REPTILES &IRCF AMPHIBIANS REPTILES • VOL &15, AMPHIBIANS NO 4 • DEC 2008 • 189 24(3):193–196 • DEC 2017 IRCF REPTILES & AMPHIBIANS CONSERVATION AND NATURAL HISTORY TABLE OF CONTENTS FEATURE ARTICLES New. ChasingDistribution Bullsnakes (Pituophis catenifer sayi) in Wisconsin: Record and Intergeneric On the Road to Understanding the Ecology and Conservation of the Midwest’s Giant Serpent ...................... Joshua M. Kapfer 190 . The Shared History of Treeboas (Corallus grenadensis) and Humans on Grenada: AmplexusA Hypothetical Excursion ............................................................................................................................ in the Malabar TreeRobert W. Toad,Henderson 198 PedostibesRESEARCH ARTICLES tuberculosus Günther 1875 . The Texas Horned Lizard in Central and Western Texas ....................... Emily Henry, Jason Brewer, Krista Mougey, and Gad Perry 204 . The Knight Anole (Anolis equestris) in Florida .............................................(Amphibia:Brian J. Camposano, KennethAnura: L. Krysko, Kevin M. Enge,Bufonidae) Ellen M. Donlan, and Michael Granatosky 212 CONSERVATION ALERT Amit Sayyed and Abhijit Nale . World’s Mammals in Crisis ............................................................................................................................................................. 220 . MoreWildlife Than Protection Mammals .............................................................................................................................. -

Maharashtra Floods: Death Toll in Pune Division Mounts to 56

follow us on reach us on app اردو ਪਜਾਬੀENGLISH ह)ी বাংলা मराठी ુજરાતી ಕನಡ த മലയാളം P* store Home Politics India Opinion Entertainment Tech Auto Buzz VideosAll SectionsCricket Pro Kabaddi LIVE TV Latest Lifestyle Photos Ganesh Chaturthi Immersives Vanity Diaries Lifestyle & Banking Swasth India NEWS18 » INDIA 1-MIN READ Maharashtra Floods: Death Toll in Pune Division Mounts to 56 With most of the rivers in Kolhapur, Sangli and Satara now owing below the danger marks, communication to almost all villages in the region has been restored. PTI Updated:August 18, 2019, 11:01 PM IST A fruit seller sits on a ooded road after monsoon rains in Nala Sopara in Palghar district of Maharashtra, Monday, Aug. 5, 2019. (PTI Photo) close Loading... Mumbai: The death toll in oods in the Pune division of Maharashtra climbed to 56 on Sunday, a senior ocer said. Out of the ve districts that fall under the administrative division, Sangli and Kolhapur were badly affected by oods in the second week of August. Maharashtra Floods: Death Toll in Pune Division Mounts to 56 Mumbai Police Trace and Return Woman's Handbag Containing … Ind Other districts in the division are Solapur, Pune and Satara. With most of the rivers in Kolhapur, Sangli and Satara now owing below the danger marks, communication to almost all villages in the region has been restored. "The death toll in oods in Kolhapur, Sangli, Satara, Solapur and Pune has reached to 56 while two persons are still missing. Most of the deaths have occurred in Kolhapur and Sangli districts, which were worst hit due to oods," said Deepak Mhaisekar, Divisional Commissioner, Pune.