Life in and Around Norton Radstock

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Background Information on Being a Trustee

Background Information on Scouting and the Scout County of Avon 1 Scout County of Avon The Scout County of Avon provides support, governance and guidance to the local Scouting community, enabling the County Commissioner Group Leaders and District Commissioners (are key volunteer managers) to deliver exciting, challenging and safe activities for the benefit of the 13,000 young people and 4,000 adults involved in Scouting in Avon. 2 What is the structure of Scouting In its operation Scouting in the United Kingdom is organised in Scout Groups, Scout Districts, Scout Counties and Country (National) Headquarters. These ‘units’ of Scouting provide: • Support • Channels for communication • Opportunities for youth Members and adults to make decisions and take responsibility • Functional units through which the design and delivery of the youth programme can be best achieved. The UK Scout Association is divided into four national groupings - England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. England is broken down into a number of counties (including Avon). The Scout County of Avon covers the geographical areas of the 4 unitary authorities of: • Bristol • Bath and North East Somerset • South Gloucester • North Somerset The Scout County of Avon is broken down into 9 Scout districts – Scout County of Avon – background information o Bath – Bath and the surrounding villages o Wansdyke – Midsomer Norton, Radstock, Keynsham, Saltford and the surrounding villages o Cotswold Edge – Thornbury, Yate and the surrounding villages that are North of the M4 and the -

Tickets Are Accepted but Not Sold on This Service

May 2015 Guide to Bus Route Frequencies Route Frequency (minutes/journeys) Route Frequency (minutes/journeys) No. Route Description / Days of Operation Operator Mon-Sat (day) Eves Suns No. Route Description / Days of Operation Operator Mon-Sat (day) Eves Suns 21 Musgrove Park Hospital , Taunton (Bus Station), Monkton Heathfield, North Petherton, Bridgwater, Dunball, Huntspill, BS 30 1-2 jnys 60 626 Wotton-under-Edge, Kingswood, Charfield, Leyhill, Cromhall, Rangeworthy, Frampton Cotterell, Winterbourne, Frenchay, SS 1 return jny Highbridge, Burnham-on-Sea, Brean, Lympsham, Uphill, Weston-super-Mare Daily Early morning/early evening journeys (early evening) Broadmead, Bristol Monday to Friday (Mon-Fri) start from/terminate at Bridgwater. Avonrider and WestonRider tickets are accepted but not sold on this service. 634 Tormarton, Hinton, Dyrham, Doyton, Wick, Bridgeyate, Kingswood Infrequent WS 2 jnys (M, W, F) – – One Ticket... 21 Lulsgate Bottom, Felton, Winford, Bedminster, Bristol Temple Meads, Bristol City Centre Monday to Friday FW 2 jnys –– 1 jny (Tu, Th) (Mon-Fri) 635 Marshfield, Colerne, Ford, Biddestone, Chippenham Monday to Friday FS 2-3 jnys –– Any Bus*... 26 Weston-super-Mare , Locking, Banwell, Sandford, Winscombe, Axbridge, Cheddar, Draycott, Haybridge, WB 60 –– (Mon-Fri) Wells (Bus Station) Monday to Saturday 640 Bishop Sutton, Chew Stoke, Chew Magna, Stanton Drew, Stanton Wick, Pensford, Publow, Woollard, Compton Dando, SB 1 jny (Fri) –– All Day! 35 Bristol Broad Quay, Redfield, Kingswood, Wick, Marshfield Monday to Saturday -

Somerset ASA Annual Development Meet 2012 - 06/10/2012 to 07/10/2012 Somerset ASA Development Meet 2012 Results

Somerset ASA Championship Meet HY-TEK's MEET MANAGER 4.0 - 3:58 PM 08/10/2012 Page 1 Somerset ASA Annual Development Meet 2012 - 06/10/2012 to 07/10/2012 Somerset ASA Development Meet 2012 Results Event 301 Girls 9 Year Olds 200 SC Meter IM Name Age Team Seed Time Finals Time 1 Charlotte Emery 9 Wellington Swimming Club NT 3:20.92 2 Eden Hartley 9 Street & District SC 3:56.51 3:43.02 3 Charlotte Orton 9 Yeovil District Swimming Club 4:30.00 4:00.87 4 Sabrina Roberts 9 Frome Swimming Club NT 4:39.00 --- Rosie Heading 9 Taunton Deane Swimming Club 3:36.04 X3:21.78 --- Madeleine Soper 9 Weston Super Mare 4:53.63 DQ Event 301 Girls 10 Year Olds 200 SC Meter IM Name Age Team Seed Time Finals Time 1 Harriett Watts 10 Yeovil District Swimming Club 3:26.95 3:08.46 2 Leah Hendrie 10 Yeovil District Swimming Club 3:24.18 3:12.62 3 Elizabeth Allen 10 Wells and Shepton 3:23.50 3:15.67 4 Sophie Holcombe 10 Yeovil District Swimming Club 3:38.71 3:18.92 5 Xanthe Dyer 10 Chard & District 3:26.25 3:20.81 6 Eleanor Harland 10 Wellington Swimming Club 3:34.16 3:22.28 7 Imy Rogers 10 Ilminster Swimming Club 3:35.00 3:22.41 8 Elizabeth Gray 10 Millfield School 3:24.40 3:24.24 9 Ruby Soper 10 Weston Super Mare 3:49.46 3:26.98 10 Elle White 10 Yeovil District Swimming Club 3:40.68 3:29.77 11 Abigail Newton 10 Taunton Deane Swimming Club 3:35.62 3:32.17 12 Charlotte Gratrick 10 Ilminster Swimming Club 3:50.00 3:33.08 13 Bethan Rees 10 Weston Super Mare 3:48.52 3:34.20 14 Amy Hubbard 10 Taunton Deane Swimming Club 3:57.69 3:40.97 15 Alice Wells 10 Norton Radstock -

Norton Radstock Town Council

MIDSOMER NORTON TOWN COUNCIL Minutes of the Meeting of the Council held in the Council Chamber at The Town Hall, Midsomer Norton on Monday 7th November 2011 Commencing at 7.00pm Present: Mayor: Cllr P Myers Deputy Mayor: Cllr Mrs L Dunford Councillors: Cllr M Evans, Cllr B Lawrence,Cllr Miss J Lewis, Cllr P Mocock, Cllr S Plumley, Cllr Mrs L Robertson, Cllr R Robertson, Cllr J Slade, Cllr S Wellington Also Present: Five Members of the Public and one Member of the Press In Attendance: Michael Curry – Town Clerk Mrs Carole Sims – Administrative Assistant 109. Fire Safety – Evacuation Procedure The Officer present explained the fire evacuation procedure as detailed in the Agenda. 110. Apologies for Absence There were no Apologies for Absence as all Members were present. 111. Mayor’s Announcements The Mayor, Councillor P Myers advised Members that exploratory discussions had taken place with Welton Rovers Football Club for a possible lunch event for children and an evening function for adults to celebrate Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee. The Mayor proposed that the item be included in the 5th December 2011 Council Agenda for discussion. The Mayor wished his thanks to be noted in respect of Bath & North East Somerset Council’s ‘Public Path Creation Order’ confirming the creation of a public bridleway at Withies Lane, Midsomer Norton. The Mayor expressed his concerns to secure the future of the two market traders who currently use West Clewes car park every Thursday. The Mayor requested that the item be included in the 5th December 2011 Council Agenda as their presence provides a local service. -

SOMERSET. {KELLY's Walrond Thomas, House Agent, See Jrames & Walrond Willcox Charles, Builder, Colenso House, Bath Hill Watts Geo

322 lU.lNSBAM. SOMERSET. {KELLY'S Walrond Thomas, house agent, see Jrames & Walrond Willcox Charles, builder, Colenso house, Bath hill Watts Geo. inspector l)f nuisances, Holnest, St.Keyna rd Willett George Gilmore Drake M.R.C.S.Eng. surgeon, &. White Ernest, ~oal merchant, see Cantle & White medical officer to the Isolation Hospital, Millward Whitfield Frederick Charles, poultry farmer, Chewton house, Bristol road Whittuck Francis Gerald, solicitor, & clerk to school Williams Charles, milk retailer, High street attendance committee, to Keynsham Rural District Willoughby Brothers, grocers, Temple street Council & to -commissioners of taxes for the Keynsham Wilts & Dorset Banking Co. Limited (agency) (Arthur union, The Avenue E. Tidmarsh, manager), High street; draw on London Wiggins E. & Sons, painters, High street County & Westminster Bank Limited, 4'r Lothbury,. Wilkins James, baker & confectioner, High street London E C Willcox John & Sons, builders, Bath hill Withers James E. draper, High street KIL:MERSDON is a very extensive parish and head of CHARLTON is a hamlet, half a mile west, and has a a petty sessional division, embracing, besides the village Primitive Methodist chapel, built in r86r. Charlton of its cwn name, the hamlets of Coleford, Charlton or House, the property of Lord Hylton, and the residence Charleton, Kilmersdon Common, Luckington, Newbury, of James Whishaw esq. is a noble mansion of stone, Highbury and Lipyeate, in .the Frome division of the occupying a prominent position in a well-timbered park county, Kilmersdon hundred, Frome union and county of 26 acres. court district, rural deanery of Midsomer Norton, arch Sexton, Alfred Padfield. deaconry of Wells and diocese of Bath and Wells. -

Community Risk Register Go to Contents Page (Click)

Avon and Somerset Community Risk Register Go to contents page (click) Avon and Somerset Community Risk Register 1 Avon and Somerset Community Risk Register Contents (Click on chapters) Introduction and Context ...........................................................................................................3 1. Emergency Management Steps ......................................................................................7 2. Avon and Somerset’s Top Risks ........................................................................................9 2.1 Flooding .............................................................................................................................................................10 2.2 Animal Disease ...............................................................................................................................................13 2.3 Industrial Action .............................................................................................................................................14 2.4 Pandemic Influenza ......................................................................................................................................15 2.5 Adverse Weather ............................................................................................................................................17 2.6 Transport Incident (including accidents involving hazardous materials) ..............................19 2.7 Industrial Site Accidents .............................................................................................................................22 -

Norton Radstock College INSPECTION REPORT: NORTON RADSTOCK COLLEGE MARCH 1999 REINSPECTION MARCH 2000

TRAINING STANDARDS COUNCIL INSPECTION REPORT MARCH 1999 REINSPECTION MARCH 2000 Norton Radstock College INSPECTION REPORT: NORTON RADSTOCK COLLEGE MARCH 1999 REINSPECTION MARCH 2000 SUMMARY Norton Radstock College offers satisfactory training in environmental conservation, engineering and business administration. Provision in animal care and horticulture is less well delivered. At the time of the first inspection, its hairdressing and printing training was less than satisfactory, but plans were well advanced to address the weaknesses. At reinspection, the hairdressing programme was satisfactory and had been subject to great improvements but these had not yet had an impact on achievement and retention rates. The problems on the printing programme were proving more intractable, and the printing training was still unsatisfactory. Policies and procedures for promoting equal opportunities are comprehensive. The college has good trainee support systems, particularly for trainees who are based largely in the college. It has good links with employers and its management of training is good. At the first inspection, quality assurance systems did not address the particular needs of work-based training, and internal verification in many occupational areas was weak. By the time of reinspection, several new quality assurance methods had been implemented, and were beginning to show results. The college was aware of the problems in printing, and was still taking action to rectify them. As a result of the reinspection of Norton Radstock College, the original published text for hair and beauty, media and design and quality assurance has been replaced by new text which makes reference to the original inspection findings. This summary page, the overall report introduction and the inspection findings introduction have also been amended to reflect the findings of the reinspection. -

Annual Report 2020/2021

AVON AND SOMERSET VIOLENCE REDUCTION UNIT Annual Report 2020/2021 SOUTH GLOUCESTERSHIRE BRISTOL NORTH SOMERSET BATH & NORTH EAST SOMERSET SOMERSET January 2021 Introduction “Serious Violence was starting to escalate in the area; lives were being lost and vulnerable people exploited daily. The police and our partners couldn’t respond to the issues in isolation, and thanks to the introduction of Violence Reduction Units (VRUs), we are now working together to make a change. “VRUs are now well established across Avon and Somerset and they continue to provide innovative and collaborative solutions to support young people in our “We welcome the announcement from communities. the Home Office of renewed funding to establish and build on a public health “Despite many challenges and increasing approach to tackling the root causes of concern due to the impact of the these terrible offences that are having a pandemic, the commitment from our devastating impact on victims, partners has been inspiring and the five perpetrators, their families and entire local VRUs have been able to make real communities. impactful change to those who need it most. “I am passionate about protecting the most vulnerable from harm and the VRUs “Our model here in Avon and Somerset is remain a crucial part in taking a unique in being a ‘hub and spoke’ compassionate approach to keeping approach, we decided to devolve the young people and our communities safe. Home Office funding to the five local authority areas (Bristol, Somerset, South “This report highlights the dedication and Gloucestershire, North Somerset and commitment from our VRU colleagues Bath and North East Somerset). -

The Forest of Avon Plan a Tree and Woodland Strategy for the West of England the FOREST of AVON PLAN Acknowledgements

The Forest of Avon Plan A Tree and Woodland Strategy for the West of England THE FOREST OF AVON PLAN Acknowledgements We would like to thank Avon Wildlife Trust, Bath Trust, Bath and North East Somerset Council, and North East Somerset Council, Bristol City Bristol Avon Catchment Partnership, Bristol Council, Bristol Water, the Forest of Avon Trust, Avon Rivers Trust, Bristol City Council, Bristol North Somerset Council, South Gloucestershire Tree Forum, Bristol Water, Cotswolds AONB, Council, Wessex Water, West of England Environment Agency, Forestry Commission, Combined Authority, and the Woodland Trust for Mendip Hills AONB, National Trust, National their support in resourcing this Strategy. Farmers Union, Natural England, North We would also like to thank the following Somerset Council, South Gloucestershire organisations for their input to and comments Council, Wessex Water, West of England on this Strategy, without whose expertise this Combined Authority and Woodland Trust. would not have been possible: Avon Wildlife While the Information in this document is considered to be correct at the date of publication, changes in circumstances after the time of publication may impact on the accuracy of the Information. 2 A TREE AND WOODLAND STRATEGY FOR THE WEST OF ENGLAND Woods and trees are vital for a healthy, happy society. They lock up carbon to fight climate change; improve our health, wellbeing and education; reduce pollution and flooding, and support people, wildlife and livestock in adapting to climate change in towns and countryside. 3 3 THE FOREST OF AVON PLAN Executive Summary A strong and improving evidence base for the Trees and woodlands are natural environment is developing, including a crucial part of the West the West of England Nature Recovery Network (NRN) and woodland opportunity mapping, and of England’s environment the West of England Joint Green Infrastructure and provide an array of Strategy (JGIS) provides a prospectus for increasing investment in green infrastructure services to our society and within the region. -

Baseline Data

Bath and North East Somerset Placemaking Plan DPD Sustainability Appraisal Scoping Report Annex B: Baseline Data Prepared for: Bath and North East Somerset Council Bath, UK Prepared by: ENVIRON Exeter, UK Date: August 2013 Project or Issue Number: UK1818391 Contract No: UK1818391 Issue: 2 Author Emma Jones (signature): Project Manager/Director Johanna Curran (signature): Date: August 2013 This report has been prepared by ENVIRON with all reasonable skill, care and diligence, and taking account of the Services and the Terms agreed between ENVIRON and the Client. This report is confidential to the client, and ENVIRON accepts no responsibility whatsoever to third parties to whom this report, or any part thereof, is made known, unless formally agreed by ENVIRON beforehand. Any such party relies upon the report at their own risk. ENVIRON disclaims any responsibility to the Client and others in respect of any matters outside the agreed scope of the Services. Version Control Record Issue Description of Status Date Reviewer Author Initials Initials A First Draft 05/12/2012 JC EJ B Second Draft 12/12/2012 JC EJ 1 Draft to Client 20/12/2012 JC EJ 2 Final issue to Client 02/09/2013 MF CM SA Scoping Report Annex B Bath and North East Somerset Council Data has been presented in the following four tables, following the format that was used for data collection for the Core Strategy SA: B&NES district data; Bath data; Keynsham data; and Midsomer Norton and Radstock data. B&NES District - Baseline data SA topic Data and quantified information Comparators or targets Trend and notes Reference Objective 1: Improve In the district as a whole between 2007 and 2009, Life expectancy has Life expectancy has been 2001 census increasing generally in the UK for the health and well- male life expectancy is 80.1 (up from 78.9 in 2011). -

Norton Radstock College

Norton Radstock College REPORT FROM THE INSPECTORATE 1998-99 THE FURTHER EDUCATION FUNDING COUNCIL THE FURTHER EDUCATION FUNDING COUNCIL The Further Education Funding Council (FEFC) has a legal duty to make sure further education in England is properly assessed. The FEFC’s inspectorate inspects and reports on each college of further education according to a four-year cycle. It also inspects other further education provision funded by the FEFC. In fulfilling its work programme, the inspectorate assesses and reports nationally on the curriculum, disseminates good practice and advises the FEFC’s quality assessment committee. College inspections are carried out in accordance with the framework and guidelines described in Council Circulars 97/12, 97/13 and 97/22. Inspections seek to validate the data and judgements provided by colleges in self-assessment reports. They involve full-time inspectors and registered part-time inspectors who have knowledge of, and experience in, the work they inspect. A member of the Council’s audit service works with inspectors in assessing aspects of governance and management. All colleges are invited to nominate a senior member of their staff to participate in the inspection as a team member. Cheylesmore House Quinton Road Coventry CV1 2WT Telephone 01203 863000 Fax 01203 863100 Website http://www.fefc.ac.uk © FEFC 1999 You may photocopy this report and use extracts in promotional or other material provided quotes are accurate, and the findings are not misrepresented. Contents Paragraph Summary Context The college and its mission 1 The inspection 6 Curriculum areas Engineering 9 Business administration 16 Health and social care 23 Humanities 29 Cross-college provision Support for students 33 General resources 40 Quality assurance 47 Governance 57 Management 64 Conclusions 74 College statistics Norton Radstock College Grade Descriptors Student Achievements Inspectors assess the strengths and weaknesses Where data on student achievements appear in of each aspect of provision they inspect. -

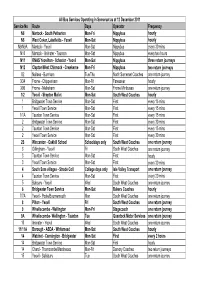

Service No Route Days Operator Frequency N6 Martock

All Bus Services Operating in Somerset as at 12 December 2011 Service No Route Days Operator Frequency N6 Martock - South Petherton Mon-Fri Nippybus hourly N8 West Coker, Lakefields - Yeovil Mon-Sat Nippybus hourly N9/N9A Martock - Yeovil Mon-Sat Nippybus every 30 mins N10 Martock - Ilminster - Taunton Mon-Sat Nippybus every two hours N11 RNAS Yeovilton - Ilchester - Yeovil Mon-Sat Nippybus three return journeys N12 Clapton/West Chinnock - Crewkerne Mon-Fri Nippybus two return journeys X2 Nailsea - Burnham Tue/Thu North Somerset Coaches one return journey X34 Frome - Chippenham Mon-Fri Faresaver hourly X96 Frome - Melksham Mon-Sat Frome Minibuses one return journey 1/2 Yeovil - Shepton Mallet Mon-Sat South West Coaches hourly 1 Bridgwater Town Service Mon-Sat First every 15 mins 1 Yeovil Town Service Mon-Sat First every 15 mins 1/1A Taunton Town Service Mon-Sat First every 15 mins 2 Bridgwater Town Service Mon-Sat First every 30 mins 2 Taunton Town Service Mon-Sat First every 15 mins 2 Yeovil Town Service Mon-Sat First every 30 mins 2S Wincanton - Oakhill School Schooldays only South West Coaches one return journey 3 Gillingham - Yeovil Fri South West Coaches one return journey 3 Taunton Town Service Mon-Sat First hourly 3 Yeovil Town Service Mon-Sat First every 30 mins 4 South Som villages - Strode Coll College days only Isle Valley Transport one return journey 4 Taunton Town Service Mon-Sat First every 20 mins 5 Babcary - Yeovil Wed South West Coaches one return journey 6 Bridgwater Town Service Mon-Sat Bakers Coaches hourly 7/7A Yeovil