The Maven Definitive Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter Index

index.fm Page 699 Monday, April 2, 2007 12:46 PM Chapter Index A Action methods, roles of, 80 AbstractFacesBean, 580 Action states, 577 accept attribute, 101 actionListener attribute, 92, 285 h:form, 104 h:command and h:commandLink, 119 acceptcharset attribute, 101 and method expressions, 69, 396 h:form, 104 MethodBinding object, 385 Accept-Language value, 45 ActionLogger class, 286 Access control application: ActionMethodBinding, 386 directory structure for, 513 Actions, 275 messages.properties, 516 ActionSource interface, 361, 385, 387, 402 noauth.html, 514 ActionSource2 interface, 359, 361, 403 UserBean.java, 515 addDataModelListener(DataModelListener web.xml, 513–514 listener), 214 accesskey attribute, 101, 109 Address book application, EJBs, 606 h:command and h:commandLink, 120 ADF Faces components set (Oracle), 613 h:outputLink, 123 Ajax: selection tags, 132 basic, with an XHR object and a AccordionRenderer class, 551 servlet (application), 530–532 action attribute, 71 components, 546–554 h:command and h:commandLink, 119 Direct Web Remoting (DWR), 543–546 method expressions, 69, 73, 396 form completion, 534–537 MethodBinding object, 385 fundamentals of, 530–533 Action events, 33, 275–284 hybrid components, 546–551 firing, 268, 418–418 JSF-Rico accordion hybrid, 548–551 Action listeners, 385 realtime validation, 537–542 compared to actions, 275 Rico accordion, 546–551 699 index.fm Page 700 Monday, April 2, 2007 12:46 PM 700 Index Ajax (cont): arg attribute, creditCardValidator, 659 transmitting JSP tag attributes to Arithmetic operators, -

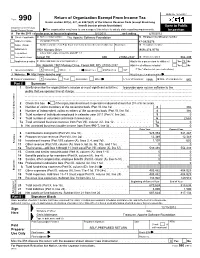

Return of Organization Exempt from Income

OMB No. 1545-0047 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax Form 990 Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except black lung benefit trust or private foundation) Open to Public Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service The organization may have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements. Inspection A For the 2011 calendar year, or tax year beginning 5/1/2011 , and ending 4/30/2012 B Check if applicable: C Name of organization The Apache Software Foundation D Employer identification number Address change Doing Business As 47-0825376 Name change Number and street (or P.O. box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number Initial return 1901 Munsey Drive (909) 374-9776 Terminated City or town, state or country, and ZIP + 4 Amended return Forest Hill MD 21050-2747 G Gross receipts $ 554,439 Application pending F Name and address of principal officer: H(a) Is this a group return for affiliates? Yes X No Jim Jagielski 1901 Munsey Drive, Forest Hill, MD 21050-2747 H(b) Are all affiliates included? Yes No I Tax-exempt status: X 501(c)(3) 501(c) ( ) (insert no.) 4947(a)(1) or 527 If "No," attach a list. (see instructions) J Website: http://www.apache.org/ H(c) Group exemption number K Form of organization: X Corporation Trust Association Other L Year of formation: 1999 M State of legal domicile: MD Part I Summary 1 Briefly describe the organization's mission or most significant activities: to provide open source software to the public that we sponsor free of charge 2 Check this box if the organization discontinued its operations or disposed of more than 25% of its net assets. -

Maven by Example I

Maven by Example i Maven by Example Ed. 0.7 Maven by Example ii Contents 1 Introducing Apache Maven1 1.1 Maven. What is it?....................................1 1.2 Convention Over Configuration...............................2 1.3 A Common Interface....................................3 1.4 Universal Reuse through Maven Plugins..........................3 1.5 Conceptual Model of a “Project”..............................4 1.6 Is Maven an alternative to XYZ?..............................5 1.7 Comparing Maven with Ant................................6 2 Installing Maven 10 2.1 Verify your Java Installation................................ 10 2.2 Downloading Maven.................................... 11 2.3 Installing Maven...................................... 11 Maven by Example iii 2.3.1 Installing Maven on Linux, BSD and Mac OS X................. 11 2.3.2 Installing Maven on Microsoft Windows...................... 12 2.3.2.1 Setting Environment Variables..................... 12 2.4 Testing a Maven Installation................................ 13 2.5 Maven Installation Details................................. 13 2.5.1 User-Specific Configuration and Repository.................... 14 2.5.2 Upgrading a Maven Installation.......................... 15 2.6 Uninstalling Maven..................................... 15 2.7 Getting Help with Maven.................................. 15 2.8 About the Apache Software License............................ 16 3 A Simple Maven Project 17 3.1 Introduction......................................... 17 3.1.1 Downloading -

Full-Graph-Limited-Mvn-Deps.Pdf

org.jboss.cl.jboss-cl-2.0.9.GA org.jboss.cl.jboss-cl-parent-2.2.1.GA org.jboss.cl.jboss-classloader-N/A org.jboss.cl.jboss-classloading-vfs-N/A org.jboss.cl.jboss-classloading-N/A org.primefaces.extensions.master-pom-1.0.0 org.sonatype.mercury.mercury-mp3-1.0-alpha-1 org.primefaces.themes.overcast-${primefaces.theme.version} org.primefaces.themes.dark-hive-${primefaces.theme.version}org.primefaces.themes.humanity-${primefaces.theme.version}org.primefaces.themes.le-frog-${primefaces.theme.version} org.primefaces.themes.south-street-${primefaces.theme.version}org.primefaces.themes.sunny-${primefaces.theme.version}org.primefaces.themes.hot-sneaks-${primefaces.theme.version}org.primefaces.themes.cupertino-${primefaces.theme.version} org.primefaces.themes.trontastic-${primefaces.theme.version}org.primefaces.themes.excite-bike-${primefaces.theme.version} org.apache.maven.mercury.mercury-external-N/A org.primefaces.themes.redmond-${primefaces.theme.version}org.primefaces.themes.afterwork-${primefaces.theme.version}org.primefaces.themes.glass-x-${primefaces.theme.version}org.primefaces.themes.home-${primefaces.theme.version} org.primefaces.themes.black-tie-${primefaces.theme.version}org.primefaces.themes.eggplant-${primefaces.theme.version} org.apache.maven.mercury.mercury-repo-remote-m2-N/Aorg.apache.maven.mercury.mercury-md-sat-N/A org.primefaces.themes.ui-lightness-${primefaces.theme.version}org.primefaces.themes.midnight-${primefaces.theme.version}org.primefaces.themes.mint-choc-${primefaces.theme.version}org.primefaces.themes.afternoon-${primefaces.theme.version}org.primefaces.themes.dot-luv-${primefaces.theme.version}org.primefaces.themes.smoothness-${primefaces.theme.version}org.primefaces.themes.swanky-purse-${primefaces.theme.version} -

Singapore Tariff Schedule

Annex 2C Tariff Schedule of Singapore See General Notes to Annex 2C for an explanation of staging codes Staging Heading H.S. Code Description Base Rates Category Chapter 1 Live animals 01.01 Live horses, asses, mules and hinnies. 0101.10.00 - Pure-bred breeding animals Free E 0101.90 - Other: 0101.90.10 - - Race horses Free E 0101.90.20 - - Other horses Free E 0101.90.90 - - Other Free E 01.02 Live bovine animals. 0102.10.00 - Pure-bred breeding animals Free E 0102.90 - Other: 0102.90.10 - - Oxen Free E 0102.90.20 - - Buffaloes Free E 0102.90.90 - - Other Free E 01.03 Live swine. 0103.10.00 - Pure-bred breeding animals Free E - Other: 0103.91.00 - - Weighing less than 50 kg Free E 0103.92.00 - - Weighing 50 kg or more Free E 01.04 Live sheep and goats. 0104.10 - Sheep: 0104.10.10 - - Pure-bred breeding Free E 0104.10.90 - - Other Free E 0104.20 - Goats: 0104.20.10 - - Pure-bred breeding animals Free E 0104.20.90 - - Other Free E Live poultry, that is to say, fowls of the species Gallus domesticus, 01.05 ducks, geese, turkeys and guinea fowls. - Weighing not more than 185 g: 0105.11 - Fowls of the species Gallus domesticus: 0105.11.10 - - - Breeding fowls Free E 0105.11.90 - - - Other Free E 0105.12 - - Turkeys: 0105.12.10 - - - Breeding turkeys Free E 0105.12.90 - - - Other Free E 0105.19 - - Other: 0105.19.10 - - - Breeding ducklings Free E 0105.19.20 - - - Other ducklings Free E 0105.19.30 - - - Breeding goslings Free E 0105.19.40 - - - Other goslings Free E 0105.19.50 - - - Breeding guinea fowls Free E 0105.19.90 - - - Other Free E - Other: 2C-Schedule-1 Staging Heading H.S. -

Apache Buildr in Action a Short Intro

Apache Buildr in Action A short intro BED 2012 Dr. Halil-Cem Gürsoy, adesso AG 29.03.12 About me ► Round about 12 Years in the IT, Development and Consulting ► Before that development in research (RNA secondary structures) ► Software Architect @ adesso AG, Dortmund ► Main focus on Java Enterprise (Spring, JEE) and integration projects > Build Management > Cloud > NoSQL / BigData ► Speaker and Author 29.03.12 2 Scala für Enterprise-Applikationen Agenda ► Why another Build System? ► A bit history ► Buildr catchwords ► Tasks ► Dependency management ► Testing ► Other languages ► Extending 3 Apache Buildr in Action – BED-Con 2012 Any aggressive Maven fanboys here? http://www.flickr.com/photos/bombardier/19428000/4 Apache Buildr in Action – BED-Con 2012 Collected quotes about Maven “Maven is such a pain in the ass” http://appwriter.com/what-if-maven-was-measured-cost-first-maven-project 5 Apache Buildr in Action – BED-Con 2012 Maven sucks... ► Convention over configuration > Inconsistent application of convention rules > High effort needed to configure ► Documentation > Which documentation? (ok, gets better) ► “Latest and greatest” plugins > Maven @now != Maven @yesterday > Not reproducible builds! ► Which Bugs are fixed in Maven 3? 6 Apache Buildr in Action – BED-Con 2012 Other buildsystems ► Ant > Still good and useful, can do everything... but XML ► Gradle > Groovy based > Easy extensible > Many plugins, supported by CI-Tools ► Simple Build Tool > In Scala for Scala (but does it for Java, too) 7 Apache Buildr in Action – BED-Con 2012 Apache -

Comparison of Four Popular Java Web Framework Implementations: Struts1.X, Webwork2.2X, Tapestry4, JSF1.2

Comparison of Four Popular Java Web Framework Implementations: Struts1.X, WebWork2.2X, Tapestry4, JSF1.2 Peng Wang University of Tampere Department of Computer Sciences Master’s thesis Supervisor: Roope Raisamo May 2008 i University of Tampere Department of Computer Sciences Peng Wang: Comparison of Java Web Framework: Struts1.X, WebWork2.2X, Tapestry4, JSF1.2 Master’s thesis, 101 pages May 2008 Java web framework has been widely used in industry Java web applications in the last few years, its outstanding MVC design concept and supported web features provide great benefits of standardizing application structure and reducing development time and effort. However, after years of evolution, numerous Java web frameworks have been invented with different focuses, it becomes increasingly difficult for developers to select a suitable framework for their web applications. In this thesis, we conduct a general comparison of four popular Java web frameworks: Struts1.X, WebWork2.2X, Tapestry 4, JSF1.2, and we try to help web developers or technique managers gain a deep insight of these frameworks through the comparison and therefore be able to choose the right framework for their web applications. The comparison preformed by this thesis generally takes three steps: first it studies the infrastructure of four chosen frameworks through which the overall view of different frameworks could be presented to readers; second it selects six basic but essential web features and fulfill the feature comparison by discussing different frameworks’ web feature implementation; third it presents a case study application to provide practical support of feature comparison. The thesis ends with an evaluation of pros and cons of different framework web features and a general suggestion of web application types that the four chosen Java web frameworks can effectively fit in. -

An Apache Princess

AN APACHE PRINCESS A Tale of the Indian Frontier BY CHARLES KING AUTHOR OF "A DAUGHTER OF THE SIOUX," "THE COLONEL'S DAUGHTER," "FORT FRAYNE," "AN ARMY WIFE," ETC., ETC. NEW YORK THE HOBART COMPANY 1903 COPYRIGHT, 1903, BY THE HOBART COMPANY. CHAPTER I THE MEETING BY THE WATERS Under the willows at the edge of the pool a young girl sat daydreaming, though the day was nearly done. All in the valley was wrapped in shadow, though the cliffs and turrets across the stream were resplendent in a radiance of slanting sunshine. Not a cloud tempered the fierce glare of the arching heavens or softened the sharp outline of neighboring peak or distant mountain chain. Not a whisper of breeze stirred the drooping foliage along the sandy shores or ruffled the liquid mirror surface. Not a sound, save drowsy hum of beetle or soft murmur of rippling waters, among the pebbly shallows below, broke the vast silence of the scene. The snow cap, gleaming at the northern horizon, lay one hundred miles away and looked but an easy one-day march. The black upheavals of the Matitzal, barring the southward valley, stood sullen and frowning along the Verde, jealous of the westward range that threw their rugged gorges into early shade. Above and below the still and placid pool and but a few miles distant, the pine-fringed, rocky hillsides came shouldering close to the[10] stream, but fell away, forming a deep, semicircular basin toward the west, at the hub of which stood bolt-upright a tall, snowy flagstaff, its shred of bunting hanging limp and lifeless from the peak, and in the dull, dirt-colored buildings of adobe, ranged in rigid lines about the dull brown, flat-topped mesa, a thousand yards up stream above the pool, drowsed a little band of martial exiles, stationed here to keep the peace 'twixt scattered settlers and swarthy, swarming Apaches. -

OSS Model Curriculum for Software Engineering Education - Skill-Sets and Sample Curriculum

Request for public comments OSS Model Curriculum for Software Engineering Education - Skill-sets and Sample curriculum - Draft 1.0 April 24, 2009 Northeast Asia OSS Promotion Forum WG2 China OSS Promotion Union Japan OSS Promotion Forum Korea OSS Promotion Forum Copyrights © NEA OSS Promotion Forum, 2009 All rights reserved. This document will be endorsed and released as CC-BY under Creative Commons License by NEA OSS Promotion Forum. Until the official release, no part of this document shall be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and microfilm without permission in writing from the NEA OSS Promotion Forum or Korea OSS Promotion Forum. 1 Each portion of this document is copyrighted by member companies and/or individuals in China OSS Promotion Union Japan OSS Promotion Forum Korea OSS Promotion Forum This document is licensed under the Creative Commons License with Attribution 2.0 international and later internationalized license (CC-BY 2.1JP / CC-BY 2.0KR / CC-BY 2.5CN) http://creativecommons.org/international/ http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.1/jp/ http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/kr/ http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/cn/ + The permission to translate original document in any kind of languages with attribution and without modification from original is allowed (This notice is possibly subject to changes). 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... -

Client-Server Web Apps with Javascript and Java

Client-Server Web Apps with JavaScript and Java Casimir Saternos Client-Server Web Apps with JavaScript and Java by Casimir Saternos Copyright © 2014 EzGraphs, LLC. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472. O’Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online editions are also available for most titles (http://my.safaribooksonline.com). For more information, contact our corporate/ institutional sales department: 800-998-9938 or [email protected]. Editors: Simon St. Laurent and Allyson MacDonald Indexer: Judith McConville Production Editor: Kristen Brown Cover Designer: Karen Montgomery Copyeditor: Gillian McGarvey Interior Designer: David Futato Proofreader: Amanda Kersey Illustrator: Rebecca Demarest April 2014: First Edition Revision History for the First Edition: 2014-03-27: First release See http://oreilly.com/catalog/errata.csp?isbn=9781449369330 for release details. Nutshell Handbook, the Nutshell Handbook logo, and the O’Reilly logo are registered trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc. Client-Server Web Apps with JavaScript and Java, the image of a large Indian civet, and related trade dress are trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and O’Reilly Media, Inc. was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in caps or initial caps. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this book, the publisher and author assume no responsibility for errors or omissions, or for damages resulting from the use of the information contained herein. -

Oracle® Private Cloud Appliance Licensing Information User Manual for Release 2.2

Oracle® Private Cloud Appliance Licensing Information User Manual for Release 2.2 E71899-01 September 2016 Oracle Legal Notices Copyright © 2013, 2016, Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. This software and related documentation are provided under a license agreement containing restrictions on use and disclosure and are protected by intellectual property laws. Except as expressly permitted in your license agreement or allowed by law, you may not use, copy, reproduce, translate, broadcast, modify, license, transmit, distribute, exhibit, perform, publish, or display any part, in any form, or by any means. Reverse engineering, disassembly, or decompilation of this software, unless required by law for interoperability, is prohibited. The information contained herein is subject to change without notice and is not warranted to be error-free. If you find any errors, please report them to us in writing. If this is software or related documentation that is delivered to the U.S. Government or anyone licensing it on behalf of the U.S. Government, then the following notice is applicable: U.S. GOVERNMENT END USERS: Oracle programs, including any operating system, integrated software, any programs installed on the hardware, and/or documentation, delivered to U.S. Government end users are "commercial computer software" pursuant to the applicable Federal Acquisition Regulation and agency-specific supplemental regulations. As such, use, duplication, disclosure, modification, and adaptation of the programs, including any operating system, integrated software, any programs installed on the hardware, and/or documentation, shall be subject to license terms and license restrictions applicable to the programs. No other rights are granted to the U.S. -

WELLINGTON-1310150-V1

Base End Code Description 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 Rate Date CHAPTER 1 LIVE ANIMALS 01.01 Live horses, asses, mules and hinnies: 0101.10.00 - Pure-bred breeding animals free free 2008 0101.90.00 - Other free free 2008 01.02 Live bovine animals: 0102.10.00 - Pure-bred breeding animals free free 2008 0102.90.00 - Other free free 2008 01.03 Live swine: 0103.10.00 - Pure-bred breeding animals free free 2008 - Other: 0103.91.00 -- Weighing less than 50 kg free free 2008 0103.92.00 -- Weighing 50 kg or more free free 2008 01.04 Live sheep and goats: 0104.10.00 - Sheep free free 2008 0104.20.00 - Goats free free 2008 01.05 Live poultry, that is to say, fowls of the species Gallus domesticus, ducks, geese, turkeys and guinea fowls: - Weighing not more than 185 g: 0105.11.00 -- Fowls of the species Gallus domesticus free free 2008 0105.12.00 -- Turkeys free free 2008 0105.19.00 -- Other free free 2008 - Other: 0105.94.00 -- Fowls of the species Gallus domesticus free free 2008 0105.99.00 -- Other free free 2008 01.06 Other live animals - Mammals: 0106.11.00 -- Primates free free 2008 0106.12.00 -- Whales, dolphins and porpoises (mammals of the order Cetacea); manatees and dugongs (mammals of the order free free 2008 Sirenia) 0106.19.00 -- Other free free 2008 0106.20.00 - Reptiles (including snakes and turtles) free free 2008 - Birds 0106.31.00 -- Birds of prey free free 2008 0106.32.00 -- Psittaciformes (including parrots, parakeets, macaws and cockatoos) free free 2008 0106.39.00 -- Other free free 2008 0106.90.00 - Other