Notes on Torch Relay Coverage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celebrities, Terrorists and the 2008 Olympic Torch Relay

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CLoK The ‘caged torch procession’: celebrities, protesters and the 2008 Olympic torch relay in London, Paris and San Francisco1 John Horne Professor of Sport and Sociology University of Central Lancashire Preston, PR1 2HE, UK. [email protected] Garry Whannel Professor of Professor of Media Cultures University of Bedfordshire Luton, UK. [email protected] For ‘Documenting the Beijing Olympics’, a Sport in Society Special Issue to be edited by D. Martinez & K Latham 5928 words inclusive The ‘caged torch procession’: celebrities, protesters and the 2008 Olympic torch relay in London, Paris and San Francisco Abstract Along with the opening and closing ceremonies one of the major non-sports events associated with the modern Olympic Games is the torch relay. Although initiated in 1936, the relay has been subject to relatively little academic scrutiny. The events of April 2008 however will have cast a long shadow on the practice. This paper focuses primarily on one week (6-13 April) in the press coverage of the 2008 torch relay as the flame made its way from London to Paris in Europe and then to San Francisco in the USA. It discusses the interpretations offered in the mediated coverage about the relay, the Olympic movement, the host city and the locations where the relay was taking place, and critically analyses the role of agencies, both for and against the Olympics, that framed the ensuing debate. 2 The ‘caged torch procession’: celebrities, protesters and the 2008 Olympic torch relay in London, Paris and San Francisco Introduction Any discussion of how a sports mega-event has been represented – visually, aurally or in print – raises questions of selection, representation and meaning. -

Gary Stadden AMPS MIBS

Mobile: 07970 667937 / Films@59: 0117 9064334 [email protected] / [email protected] www.garystadden.com / www.filmsat59.com/people/gary-stadden Various Production Credits: Programme Client Broadcaster Format Entertainment: Turn Back Time: The High Street Wall To Wall BBC1 XDCam The Restaurant (1, 2 & 3) BBC BBC2 Hi Def 60 Minute Makeover (1 to 11) ITV Productions ITV1 Digi Beta Rosemary Shrager`s School For Cooks (1 & 2) RDF Media West ITV1 DVCam Dickinson’s Real Deal (3 to 10) RDF Media West ITV1 DVCam Live n Deadly BBC Bristol CBBC / BBC2 DVCam Sorcerer’s Apprentice Twenty Twenty BBC2 / CBBC DVCam James May’s Toy Stories Plum Pictures BBC2 Digi Beta Red or Black Syco ITV1 XDCam Come Dine With Me Granada London Channel 4 DVCam The X Factor / Xtra Factor Talkback Thames / Syco ITV1 / ITV2 Digi Beta Deal Or No Deal: Live Endemol West Channel 4 DVCam The Biggest Loser Shine TV ITV1 XDCam Grand Designs Talkback Thames Channel 4 XDCam Great Welsh Adventure With Griff Rhys Jones Modern Television ITV1 F5 / SD664 Homes Under The Hammer Lion Television BBC1 Digi Beta Dogs: Their Secret Lives (1 & 2) Arrow Media Channel 4 C300/SD664 Time Team Videotext Communications Channel 4 Digi Beta Ade In Britain Shiver ITV1 XDCam Dancing On Ice ITV Productions ITV1 Digi Beta Naomi’s Nightmares Of Nature BBC Bristol CBBC XDCam Escape To The Country Talkback Thames BBC2 DVCam The Apprentice (1 & 2) Talkback Thames BBC2 Digi Beta Britain’s Got Talent Talkback Thames / Syco ITV1 Digi Beta Celebrity Wedding Planner Renegade Picture Channel 5 XDCam Homes -

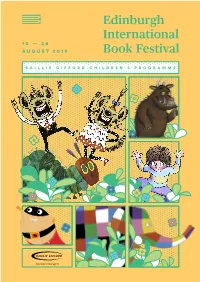

W E N E E D N E W S T O R I

10 — 26 AUGUST 2019 BAILLIEWE GIFFORD NEED CHILDREN’SNEW STORIES PROGRAMME Investment managers 01 THE ATMOSPHERE AT THE BOOK “ FESTIVAL IS BRILLIANT. WE WERE ” OVERWHELMED BY THE CHOICE IN THE KIDS' PROGRAMME – A GREAT DAY OUT. VERY INSPIRING FOR YOUNG 'WANT TO BE' WRITERS. AUDIENCE MEMBER FREE ENTRY TO THE BOOK FESTIVAL VILLAGE Relax with a picnic, browse the bookshops or take part in exciting free activities every day 92 SOAR WITH DRAGONS VANQUISH VICIOUS VIKINGS CUDDLE UP WITH A PATCHWORK ELEPHANT SNACK WITH A VERY HUNGRY CATERPILLAR Step into a place filled with imagination and magic. GET INVOLVED IN OVER 200 When Edinburgh is packed with August crowds, INTERACTIVE EVENTS the Book Festival Village becomes another world; Dive into the following pages for the full range of events for all it’s your space to explore, relax, create and spot as ages from tiny tots to teens. There are crafty activities for little many of your favourite book characters as you can. ones to bring storytime alive, sensational stories from David Almond, Philip Ardagh and Cressida Cowell for older kids, and high-powered events for teens covering everything from tough ALL EVENTS FREE OR £5.00 topics to side-splitting comedy. There are plenty of opportunities to get creative with daily free drop-in activities in the Baillie Gifford Story Box (open every day from 11:00-16:30). MEET YOUR HEROES From asking your burning questions, to getting your most-loved book signed, to joining them for engaging activities, now is your chance to spend some quality time with your favourite authors and illustrators, learn all about the magic of crafting stories and have fun with them too. -

New Titles July-December

New Titles July - December 2020 New Titles July-December 2020 BIG PICTURE PRESS TEMPLAR BOOKS BONNIER P I C C A D I L LY PRESS HOT KEY BOOKS BOOKS UK CHILDREN ’ S Cover illustration copyright © 2020 by Ximo Abadía from The Extraordinary Elements CONTENTS Big Picture Press 3 Templar Books 17 Piccadilly Press 37 Hot Key Books 43 Contacts 50 Fungarium Ester Gaya & Katie Scott Welcome to the Fungarium! A BIG HELLO Step into the world of fungi and JULY learn all about these strange and fascinating life forms. Illustrator Katie Scott returns to the Welcome to the Museum series with exquisite, detailed images of some of the most fascinating living organisms on this planet - fungi. From the Big Picture Press books are objects to be Piccadilly Press books are fun, family- fungi we see on supermarket shelves pored over and then returned to again and orientated stories in any genre, that possess to fungi like penicillium that have again, created by and made for the incurably the ability to capture readers’ imagination shaped human history, this is the curious. Having made an indelible mark on and inspire them to develop a life-long love definitive introduction to what fungi the children’s non-fiction market with their of reading. Our titles can be standalone are and just how vital they are to boutique range of illustrated gift books, they stories or part of a series, using design and the world's ecosystem. Created in create visually inspiring books for readers of illustration that is integral to the content collaboration with the Royal Botanic all ages around the world. -

9 February 2018 Page 1 of 12 SATURDAY 03 FEBRUARY 2018 Duck, and Baking a Camembert Without Ruining It

Radio 4 Listings for 3 – 9 February 2018 Page 1 of 12 SATURDAY 03 FEBRUARY 2018 duck, and baking a camembert without ruining it. on to write as an adult. SAT 00:00 Midnight News (b09ppzvr) They also investigate Bath's rich culinary history, passing "An autobiography is a book a person writes about his own life. The latest national and international news from BBC Radio 4. judgement on everything from Bath Chaps to Bath Olivers. It is usually full of all sorts of boring details. This is not an Followed by Weather. autobiography." Produced by Hannah Newton Assistant Producer: Laurence Bassett The story of Roald Dahl's childhood is filled with excitement SAT 00:30 Book of the Week (b09ppwdv) and wonder but also terror and great sadness. We learn of his No Place to Lay One's Head, Episode 5 Food Consultant: Anne Colquhoun experiences at cruel boarding schools, his daring Great Mouse Francoise Frenkel's real life story of flight from Berlin on the Plot, the dangers of Boazers, the pleasure/pain of the local 'night of broken glass'. A Somethin' Else production for BBC Radio 4. sweetshop and his time as a chocolate taster. Just some of the marvellous, extraordinary events that no doubt went on to An escape attempt with the 'smuggler' goes wrong. The author inspire his best-selling books. is apprehended and will face a trial in Saint-Julien. Things look SAT 11:00 The Week in Westminster (b09q9yx0) bleak for the future, but again the kindness of strangers will Kate McCann of The Daily Telegraph looks behind the scenes Patrick Malahide provides the voice of Dahl in a colourful prevail. -

Diverse on Screen Talent Directory

BBC Diverse Presenters The BBC is committed to finding and growing diverse onscreen talent across all channels and platforms. We realise that in order to continue making the BBC feel truly diverse, and improve on where we are at the moment, we need to let you know who’s out there. In this document you will find biographies for just some of the hugely talented people the BBC has already been working with and others who have made their mark elsewhere. It’s the responsibility of every person involved in BBC programme making to ask themselves whether what, and who, they are putting on screen reflects the world around them or just one section of society. If you are in production or development and would like other ideas for diverse presenters across all genres please feel free to get in touch with Mary Fitzpatrick Editorial Executive, Diversity via email: [email protected] Diverse On Screen Talent Directory Presenter Biographies Biographies Ace and Invisible Presenters, 1Xtra Category: 1Xtra Agent: Insanity Artists Agency Limited T: 020 7927 6222 W: www.insanityartists.co.uk 1Xtra's lunchtime DJs Ace and Invisible are on a high - the two 22-year-olds scooped the gold award for Daily Music Show of the Year at the 2004 Sony Radio Academy Awards. It's a just reward for Ace and Invisible, two young south Londoners with high hopes who met whilst studying media at the Brits Performing Arts School in 1996. The 'Lunchtime Trouble Makers' is what they are commonly known as, but for Ace and Invisible it's a story of friendship and determination. -

The Beijing Olympics Political Impact and Implications for Soft Power Politics

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive DSpace Repository Theses and Dissertations 1. Thesis and Dissertation Collection, all items 2008-12 The Beijing Olympics political impact and implications for soft power politics Granger, Megan M. Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/3845 Downloaded from NPS Archive: Calhoun NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS THE BEIJING OLYMPICS: POLITICAL IMPACT AND IMPLICATIONS FOR SOFT POWER POLITICS by Megan M. Granger December 2008 Thesis Advisor: Alice Miller Second Reader: Robert Weiner Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED December 2008 Master’s Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE: The Beijing Olympics: Political Impact and 5. FUNDING NUMBERS Implications for Soft Power Politics 6. AUTHOR Megan M. Granger 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION Naval Postgraduate School REPORT NUMBER Monterey, CA 93943-5000 9. -

Human Rights in China Homework Booklet

Human Rights in China Homework Booklet Homework Task One At home try to find 10 items in your house which were made in China. Make a list of these items in your class work jotter. Homework Task Two Imagine you are a prisoner in a Chinese Labour camp. Write a diary entry of what life is like in the camp on a typical day. You can use the information from the booklet to help form your diary entry. You could also use the experiences of Harry Wu to help you. This piece of work should be about a jotter page in length. Homework Task Three Internet Research Task! 1. Find three reasons why the Chinese government implemented the One Child Policy in the 1970’s. 2. Find three problems that the One Child Policy has caused. Complete this task in your jotter. Homework Task Four Read the following article taken from the BBC news website and answer the following questions. You will be expected to discuss your answers in class. Answer questions in full sentences. Arrests at Olympic torch relay Police arrested 35 people when clashes broke out as the Olympic torch was carried on a relay through London on its way to the 2008 games in China. Protesters are upset about the way China rules Tibet, and the way the Chinese Government treats Tibetan people. Some campaigned quietly while others tried to disrupt the torch's journey. Protests continued all day, with someone trying to snatch the torch from former Blue Peter host Konnie Huq. Police changed the route the torch was taking incase of further trouble and at some points it was carried on a bus, instead of by a runner. -

Konnie & Dr Rupa

I Wish I Was An Only Child – Konnie & Dr Rupa Huq [Guitar and flute music] RACHEL MASON: Welcome to I Wish I Was An Only Child, with me, Rachel Mason – CATHY MASON: And me, Cathy Mason. RACHEL: Where we speak to other siblings about the dynamic of their relationship to see where we’re going wrong. CATHY: This week, we spoke to presenter, screenwriter, and children’s author Konnie Huq. RACHEL: And her sister, Labour MP, columnist, and academic Dr Rupa Huq. [Flute sounds] RACHEL: Welcome! Hello! CATHY: Welcome! RACHEL: Thank you for doing this. Thank you for chatting to us. CATHY: Thank you, thank you, thank you. The question we ask everybody at the beginning: who’s the funniest? KONNIE HUQ: Oh, definitely her. DR RUPA HUQ: I would say actually her. Her? Which is – 1 KONNIE: This is the thing – you know what? RUPA: This is exactly what it is. KONNIE: We’re a different type of funny. I’d say you’re sort of more dry and acerbic, and I’m just warm and funny. [laughs] No, I don’t know. RUPA: Funny peculiar, I win that one. KONNIE: You can judge throughout this podcast. RUPA: Yeah, yeah. KONNIE: By the end of it, you’ll go, ‘my gosh, Konnie is so unfunny! It’s definitely Rupa that wins.’ RUPA: No, you’ll be in hoots of laughter. RACHEL: So – so – we should give it some context that there’s three years between you. Three years’ age difference, right? And you’ve got – there’s a third sibling, Newton, yes? Who’s the oldest. -

British Film Institute

British Telephone Film Institute +44 (0)20 7255 1444 Annual Review 21 Stephen Street Facsimile British 2000/2001 London +44 (0)20 7436 0439 W1T 1LN Email Film Institute UK [email protected] Website www.bfi.org.uk April 2000 May 2000 June 2000 July 2000 August 2000 September 2000 October 2000 November 2000 December 2000 January 2001 February 2001 March 2001 14th London Lesbian and Silent Shakespeare International Federation bfi DVD release: Man with NFT seasons on Marcello bfi TV 100, list of favourite bfi Theatrical Release: Some The 44th bfi Regus London December bfi website Successful launch of the Joseph Losey’s M (1951) John Cassavetes season Gay Film Festival (LLGFF) compilation released of Film Archives (FIAF) a Movie Camera the first Mastroianni, the Olympics British television Like It Hot (sponsored by Film Festival (RLFF) formally accepted as part bfi Avant Garde video series restored and now available at the NFT on DVD in US Congress at NFT and the picture disk DVD released and films linked to Citizen programmes announced Accenture) and Salò of the National Grid for Sergio Leone season at NFT J Paul Getty Conservation in the UK Kane First screening of the silent Learning Robert Altman receives the Re-release of Breakfast The Tongues on Fire Online purchase of Sight Centre Overseas bookings were Restoration of Paul Czinner’s film Lady Windermere’s Fan 52nd bfi fellowship at Tiffany’s (sponsored by Asian Women’s Film Festival John Hurt Guardian Interview and Sound magazine set up Acquired the ground-breaking Lambeth Education -

Thanks for Life – End Polio

ROTARY IN LONDON COMMUNICATIONS NEWSLETTER THANKS FOR LIFE EDITION - FEBRUARY 2010 EVE CONWAY, COMMUNICATIONS CHAIRMAN Thanks for Life – Rotary Day on 23rd February Thanks for Life week is nearly upon us and hopefully clubs have all of their preparations in place by now including a Window of Opportunity and arrangements for collection and membership initiatives at the 13 designated Tesco stores and the local branch of Sainsbury’s. Please make sure that your local media have been informed in advance of everything that you are planning to do so that PR coverage can be maximized. If you haven’t seen the excellent video of the November sub national immunization days involving 86 Rotarians and fronted by TV Presenter Konnie Huq, it has now been put onto YouTube. You can access both parts of it via the Thanks for Life website by ctrl+clicking here and following the links or you can go to:http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HZp1VNr44Bw http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-qFQiIdhgmE&feature=related It really is well worth watching especially to put you in the right mindset for Thanks for Life week. Thanks for Life – End Polio Now ROTARY DAY - Thanks for Life Day is on Rotary’s 105th birthday on 23rd February, 2010 and it really is crucial for clubs to finalize their plans for this vitally important initiative. It is, of course, a tremendous opportunity to combine fundraising for polio eradication and membership recruitment. For those clubs who have been given the opportunity to collect outside 13 Tesco’s stores in the London district on 27th February, please try to ensure that these arrangements include having the facility of an information point manned by a separate Membership Awareness team who are additional to your collectors. -

Kadhim Shubber NEWS [email protected]

12 The award-winning student newspaper of Imperial College . 02 “Keep The Cat Free” . Issue 1,453 10 ffelixelix felixonline.co.uk Charging onwards This week.... Five years behind bars: Imperial’s University Challenge team speak Gary Tanaka sentenced ahead of their next match, see page 6 and 7 News, Page 3 Causing a stir: The Pope misunderstood? Politics, Page 15 Ilustrating every lyric: The Hard Rain Project Arts, Page 17 Boxing at Imperial: Preying on false hopes The historical Rector’s Cup felix investigates the ‘model casting’ scam that is targeting students on High Street Kensington, see page 4 Features, Page 37 2 felix FRIDAY 12 FEBRUARY 2010 News Editor Kadhim Shubber NEWS [email protected] New Guilds President found The world beyond AAlexanderlexander KKarapetianarapetian College walls Following the departure of Kirsty Pat- terson, former CGCU President, the City and Guilds College Union held elections to appoint a new President and Guildsheet Editor. The elections attracted respective candidates Dan Lundy and Richard Bennett, who at- tained their positions unopposed. Guildsheet is the monthly student Sri Lanka magazine of the Faculty of Engineer- ing, rival to the Royal College Of Sci- New CGCU President Dan Lundy being unfairly engulfed by the CGCU logo eneral Sarath Fonseka, the loser of Sri Lanka’s presidential ence Union’s Broadsheet magazine. election last month and the commander of the Sri Lankan The results of the elections were an- G army during the conclusion of the Sri Lankan civil war, was nounced at noon on Monday. The the Presidential position. team will focus on attaining sponsor- arrested Monday in a raid on his offices.