Bushmaster (Lachesis Muta) Predatory Behavior at Dallas Zoo and San Diego Zoo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Record of the Occurrence of Lachesis Muta (Serpentes, Viperidae) in an Atlantic Forest Fragment in Paraíba, Brazil, with Comments on the Species’ Preservation Status

Biotemas, 26 (2): 283-286, junho de 2013 doi: 10.5007/2175-7925.2013v26n2p283283 ISSNe 2175-7925 Short Communication Record of the occurrence of Lachesis muta (Serpentes, Viperidae) in an Atlantic Forest fragment in Paraíba, Brazil, with comments on the species’ preservation status Ricardo Rodrigues 1* Ralph Lacerda de Albuquerque 1 Diego José Santana 1 Daniel Orsi Laranjeiras 1 Arielson Santos Protázio 1 Frederico Gustavo Rodrigues França 2 Daniel Oliveira Mesquita 1 1 Universidade Federal da Paraíba, Centro de Ciências Exatas e da Natureza Departamento de Sistemática e Ecologia, Laboratório de Herpetologia, Cidade Universitária CEP 58059-900, João Pessoa – PB, Brazil 2 Universidade Federal da Paraíba, Centro de Ciências Aplicadas e Educação, Campus IV, Litoral Norte Rua da Mangueira, s/n, CEP 58297-000, Rio Tinto – PB, Brazil *Corresponding author [email protected] Submetido em 16/07/2012 Aceito para publicação em 19/01/2013 Resumo Registro de ocorrência de Lachesis muta (Serpentes, Viperidae) em um fragmento de Mata Atlântica na Paraíba, Brasil, com comentários sobre o status de preservação da espécie. Neste estudo é descrito um novo registro da serpente pico-de-jaca, Lachesis muta, em um fragmento de Mata Atlântica no estado da Paraíba, Nordeste do Brasil. Essa espécie é considerada a maior das serpentes peçonhentas do Novo Mundo. O espécime foi encontrado durante a noite, cruzando um atalho estreito, próximo a um declive, a aproximadamente 20m de uma queda d’água. A ocorrência de L. muta nesse fragmento demonstra a importância da conservação dos fragmentos de Mata Atlântica para a preservação dessa espécie. Palavras-chave: Conservação; Lachesis muta; Mata Atlântica; Surucucu-pico-de-jaca; Viperidae Abstract In this study, one describes a new record of the bushmaster snake, Lachesis muta, in an Atlantic Forest fragment in the state of Paraíba, northeastern Brazil. -

Characterization of a Hemorrhage-Inducing Component Present in Bitis Arietans Venom

Vol. 14(12), pp. 999-1008, 25 March, 2015 DOI: 10.5897/AJB2014.14319 Article Number: AF0A87151680 ISSN 1684-5315 African Journal of Biotechnology Copyright © 2015 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/AJB Full Length Research Paper Characterization of a hemorrhage-inducing component present in Bitis arietans venom Tahís Louvain de Souza1, Fábio C. Magnoli2 and Wilmar Dias da Silva2* 1Laboratório de Biologia do Reconhecer, Centro de Biociências e Biotecnologia, Universidade Estadual do Norte Fluminense Darcy ribeiro, Campos dos Goytacazes, RJ, Brazil. 2Laboratório de Imunoquímica, Instituto Butantan, São Paulo, SP , Brazil. Received 13 November, 2014; Accepted 16 February, 2015 Better characterization of individual snake venom toxins is useful for analyzing the association of their toxic domains and relevant antigenic epitopes. Here we analyzed the Bitis arietans hemorrhagic- inducing toxin present in a representative venom sample. Among the 1´ to 5´ protein peaks isolated using a Sephacryl S 100 HR chromatography column, hemorrhagic activity was expressed by all according to the following intensity, P´5 > P´3 > P´2 >, P´4. The proteins were recognized and measured with antibodies present in polyvalent horse F(ab)´2 anti-B. arietans, Bitis spp., Lachesis muta, B. atrox, Bothrops spp., Crotalus spp., and Naja spp. or in IgY anti-B. arietans and anti-Bitis spp. using enzyme- linked immunosorbent assays and western blotting. In addition, in an in vitro-in vivo assay these anti- venoms were able to block hemorrhagic-inducing activity. The evident cross-reactivity expressed by different specific anti-venoms indicates that metalloproteinases induce an immunological signature indicating the presence of similar antigenic epitopes for several snake venoms. -

The Search for Natural and Synthetic Inhibitors That Would Complement Antivenoms As Therapeutics for Snakebite Envenoming

toxins Review The Search for Natural and Synthetic Inhibitors That Would Complement Antivenoms as Therapeutics for Snakebite Envenoming José María Gutiérrez 1,* , Laura-Oana Albulescu 2, Rachel H. Clare 2, Nicholas R. Casewell 2 , Tarek Mohamed Abd El-Aziz 3,4 , Teresa Escalante 1 and Alexandra Rucavado 1 1 Facultad de Microbiología, Instituto Clodomiro Picado, Universidad de Costa Rica, San José 11501, Costa Rica; [email protected] (T.E.); [email protected] (A.R.) 2 Centre for Snakebite Research & Interventions, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, Liverpool L3 5QA, UK; [email protected] (L.-O.A.); [email protected] (R.H.C.); [email protected] (N.R.C.) 3 Zoology Department, Faculty of Science, Minia University, El-Minia 61519, Egypt; [email protected] 4 Department of Cellular and Integrative Physiology, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX 78229-3900, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: A global strategy, under the coordination of the World Health Organization, is being unfolded to reduce the impact of snakebite envenoming. One of the pillars of this strategy is to ensure safe and effective treatments. The mainstay in the therapy of snakebite envenoming is the administration of animal-derived antivenoms. In addition, new therapeutic options are being explored, including recombinant antibodies and natural and synthetic toxin inhibitors. In this review, snake venom toxins are classified in terms of their abundance and toxicity, and priority Citation: Gutiérrez, J.M.; Albulescu, actions are being proposed in the search for snake venom metalloproteinase (SVMP), phospholipase L.-O.; Clare, R.H.; Casewell, N.R.; A2 (PLA2), three-finger toxin (3FTx), and serine proteinase (SVSP) inhibitors. -

Inflammatory Oedema Induced by Lachesis Muta Muta

Toxicon 53 (2009) 69–77 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Toxicon journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/toxicon Inflammatory oedema induced by Lachesis muta muta (Surucucu) venom and LmTX-I in the rat paw and dorsal skin Tatiane Ferreira a, Enilton A. Camargo a, Maria Teresa C.P. Ribela c, Daniela C. Damico b, Se´rgio Marangoni b, Edson Antunes a, Gilberto De Nucci a, Elen C.T. Landucci a,b,* a Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medical Sciences (FCM), UNICAMP, PO Box 6111, 13084-971 Campinas, SP, Brazil b Department of Biochemistry, Institute of Biology (IB), UNICAMP, PO Box 6109, 13083-970 Campinas, SP, Brazil c Department of Application of Nuclear Techniques in Biological Sciences, IPEN/CNEN, Sa˜o Paulo, SP, Brazil article info abstract Article history: The ability of crude venom and a basic phospholipase A2 (LmTX-I) from Lachesis muta muta Received 7 June 2008 venom to increase the microvascular permeability in rat paw and skin was investigated. Received in revised form 12 October 2008 Crude venom or LmTX-I were injected subplantarly or intradermally and rat paw oedema Accepted 16 October 2008 and dorsal skin plasma extravasation were measured. Histamine release from rat perito- Available online 1 November 2008 neal mast cell was also assessed. Crude venom or LmTX-I induced dose-dependent rat paw oedema and dorsal skin plasma extravasation. Venom-induced plasma extravasation was Keywords: inhibited by the histamine H antagonist mepyramine (6 mg/kg), histamine/5-hydroxy- Snake venom 1 Vascular permeability triptamine antagonist cyproheptadine (2 mg/kg), cyclooxygenase inhibitor indomethacin Mast cells (5 mg/kg), nitric oxide synthesis inhibitor L-NAME (100 nmol/site), tachykinin NK1 Sensory fibres antagonist SR140333 (1 nmol/site) and bradykinin B2 receptor antagonist Icatibant Lachesis muta muta (0.6 mg/kg). -

For Specific Identification of Lachesis Acrochorda Venom

The Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins including Tropical Diseases ISSN 1678-9199 | 2012 | volume 18 | issue 2 | pages 173-179 Development of a sensitive enzyme immunoassay (ELISA) for specific ER P identification of Lachesis acrochorda venom A P Núñez Rangel V (1, 2), Fernández Culma M (1), Rey-Suárez P (1), Pereañez JA (1, 3) RIGINAL O (1) Program of Ophidism and Scorpionism, University of Antioquia, Medellin, Colombia; (2) School of Microbiology, University of Antioquia, Medellin, Colombia; (3) School of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, University of Antioquia, Medellin, Colombia. Abstract: The snake genus Lachesis provokes 2 to 3% of snakebites in Colombia every year. Two Lachesis species, L. acrochorda and L. muta, share habitats with snakes from another genus, namely Bothrops asper and B. atrox. Lachesis venom causes systemic and local effects such as swelling, hemorrhaging, myonecrosis, hemostatic disorders and nephrotoxic symptoms similar to those induced by Bothrops, Portidium and Bothriechis bites. Bothrops antivenoms neutralize a variety of Lachesis venom toxins. However, these products are unable to avoid coagulation problems provoked by Lachesis snakebites. Thus, it is important to ascertain whether the envenomation was caused by a Bothrops or Lachesis snake. The present study found enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) efficient for detecting Lachesis acrochorda venom in a concentration range of 3.9 to 1000 ng/mL, which did not show a cross-reaction with Bothrops, Portidium, Botriechis and Crotalus venoms. Furthermore, one fraction of L. acrochorda venom that did not show cross- reactivity with B. asper venom was isolated using the same ELISA antibodies; some of its proteins were identified including one Gal-specific lectin and one metalloproteinase. -

Experimental Lachesis Muta Rhombeata Envenomation and Effects of Soursop (Annona Muricata) As Natural Antivenom

Universidade de São Paulo Biblioteca Digital da Produção Intelectual - BDPI Departamento de Microbiologia - ICB/BMM Artigos e Materiais de Revistas Científicas - FCFRP/DFQ 2016 Experimental Lachesis muta rhombeata envenomation and effects of soursop (Annona muricata) as natural antivenom Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins including Tropical Diseases. 2016 Mar 08;22(1):12 http://www.producao.usp.br/handle/BDPI/49930 Downloaded from: Biblioteca Digital da Produção Intelectual - BDPI, Universidade de São Paulo Cremonez et al. Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins including Tropical Diseases (2016) 22:12 DOI 10.1186/s40409-016-0067-6 RESEARCH Open Access Experimental Lachesis muta rhombeata envenomation and effects of soursop (Annona muricata) as natural antivenom Caroline Marroni Cremonez1, Flávia Pine Leite1, Karla de Castro Figueiredo Bordon1, Felipe Augusto Cerni1, Iara Aimê Cardoso1, Zita Maria de Oliveira Gregório2, Rodrigo Cançado Gonçalves de Souza3, Ana Maria de Souza2 and Eliane Candiani Arantes1* Abstract Background: In the Atlantic forest of the North and Northeast regions of Brazil, local population often uses the fruit juice and the aqueous extract of leaves of soursop (Annona muricata L.) to treat Lachesis muta rhombeata envenomation. Envenomation is a relevant health issue in these areas, especially due to its severity and because the production and distribution of antivenom is limited in these regions. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the relevance of the use of soursop leaf extract and its juice against envenomation by Lachesis muta rhombeata. Methods: We evaluated the biochemical, hematological and hemostatic parameters, the blood pressure, the inflammation process and the lethality induced by Lachesis muta rhombeata snake venom. -

Phylogenetic Relationships Within Bothrops Neuwiedi Group

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 71 (2014) 1–14 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Phylogenetic relationships within Bothrops neuwiedi group (Serpentes, Squamata): Geographically highly-structured lineages, evidence of introgressive hybridization and Neogene/Quaternary diversification ⇑ Taís Machado a, , Vinícius X. Silva b, Maria José de J. Silva a a Laboratório de Ecologia e Evolução, Instituto Butantan, Av. Dr. Vital Brazil, 1500, São Paulo, SP 05503-000, Brazil b Coleção Herpetológica Alfred Russel Wallace, Instituto de Ciências da Natureza, Universidade Federal de Alfenas, Rua Gabriel Monteiro da Silva, 700, Alfenas, MG 37130-000, Brazil article info abstract Article history: Eight current species of snakes of the Bothrops neuwiedi group are widespread in South American open Received 8 November 2012 biomes from northeastern Brazil to southeastern Argentina. In this paper, 140 samples from 93 different Revised 3 October 2013 localities were used to investigate species boundaries and to provide a hypothesis of phylogenetic rela- Accepted 5 October 2013 tionships among the members of this group based on 1122 bp of cyt b and ND4 from mitochondrial DNA Available online 17 October 2013 and also investigate the patterns and processes occurring in the evolutionary history of the group. Com- bined data recovered the B. neuwiedi group as a highly supported monophyletic group in maximum par- Keywords: simony, maximum likelihood and Bayesian analyses, as well as four major clades (Northeast I, Northeast Mitochondrial DNA II, East–West, West-South) highly-structured geographically. Monophyly was recovered only for B. pubes- Incomplete lineage sorting Hybrid zone cens. -

Lachesis Stenophrys) in a European Zoo

The Herpetological Bulletin 151, 2020: 24-27 SHORT NOTE https://doi.org/10.33256/hb151.2427 First report of reproduction in captivity of the Central American bushmaster (Lachesis stenophrys) in a European zoo ÁLVARO CAMINA1*, NICOLÁS SALINAS, IGNACIO GARCIA-DELGADO1, BORJA BAUTISTA1,2, GUILLERMO RODRIGUEZ1, RUBÉN ARMENDARIZ1, LORENZO DI IENNO2, ALICIA ANGOSTO3, RUBÉN HERRANZ4 & GREIVIN CORRALES5 1Grupo Atrox, Parque Temático de la Naturaleza Faunia Avenida de las Comunidades, 28 28032 Madrid, Spain 2Mastervet Mirasierra, Calle de Nuria, 57, 28034 Madrid, Spain 3Alicia Angosto Ecografía Veterinaria, Mallorca, Spain 4Zoopinto, Camino de San Antón, 6, 28320 Pinto, Madrid, Spain 5Instituto Clodomiro Picado, Sección Serpentario, Facultad de Microbiología, Universidad de Costa Rica, San José, Costa Rica *Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected] he Central American bushmaster (Lachesis stenophrys) T(Fig.1) is a large species of pit viper. The males are a little longer than the females, averaging of 2-2.10 m and 1.9-2.05 m respectively (Solórzano, 2004). The species lives along the Caribbean versant of Nicaragua to western and central Panama (Campbell & Lamar, 2004), and in Costa Rica is found in tropical wet and subtropical rainforest on the Caribbean versant (Corrales et al., 2014) where the rainfall is very high (3500-6000 mm annual range). Although it can be found at altitudes of 100-700 m its preferences are thought to be 200- 400 m (Ripa, 2002). Lachesis spp. are the only pit vipers on the American continent that lay eggs instead of giving birth to live young (Campbell & Lamar, 2004; Solórzano, 2004). The eggs are deposited in subterranean cavities and the shelters of Figure 1. -

Peru Amarakaeri Communal Reserve

Park Profile - Peru Amarakaeri Communal Reserve Date of last field evaluation: April 2003 Date published: May 2003 Location: District of Madre de Dios, province of Manu, department of Madre de Dios and district of Pilcopata, province of Paucartambo, department of Cuzco. Year created: 2002 Area: 402,335.62 ha Eco-region: Southwestern Amazonian moist forests, Peruvian yungas. Habitats: Subtropical humid forests, subtropical rainforest, semi-flooded subtropical rainforest Summary Description Amarakaeri Communal Reserve is located in the department of Madre de Dios between Manu National Park, Tambopata National Reserve and Bahuaja-Sonene National Park. It forms part of an international conservation corridor that includes protected areas in Bolivia and Brazil. It features a typical tropical humid climate, with plains and winding rivers in the lowlands and mountain ranges and deep gorges in the highlands. Biodiversity Amarakaeri Communal Reserve has a wide range of life zones and high biological diversity. The forest features varied plant life due to the altitudinal ranges, and a large number of species are found throughout different forest regions. The area is home to species such as the giant river otter, jaguar, black spider monkey, spectacled bear, macaw and helmeted curassow. 1 Amarakaeri Communal Reserve—Peru www.parkswatch.org Threats ParksWatch classifies this protected area as vulnerable, meaning that there is a high risk that the area will fail to protect and maintain biological diversity in the medium-term future if current trends -

Download Detailed Program

Venomous snakes as flagship species 10, 11 & 12 october 2019 Bryan Fry Venom Evolution Lab, School of Biological Sciences, University of Queensland Bryan Fry has a PhD in Biochemistry and is a Professor in Toxicology at the University of Queensland. His research focuses on how natural and unnatural toxins affect human health and the natural world, and what can be done to stop or reverse these effects. He is the author of two books and over 130 scientific papers. He has lead scientific expeditions to over 40 countries, including Antarctica, and has been inducted into the elite adventurer society The Explorers Club. He lives in Brisbane with his wife Kristina and two dogs Salt and Pepper. Thursday October 10: 09.20 – 09.45h having the capacity to neutralise the effects of Maintaining venomous animal collections: envenomations of non-PNG taipans, this antivenom protocols and occupational safety. may have the capacity to neutralise coagulotoxins For herpetologists, toxinologists, venom producers, in venom from closely related brown snakes and zookeepers, maintenance of a healthy collection (Pseudonaja spp.) also found in PNG. Consequently, of animals for research, venom extraction purposes, we investigated the cross-reactivity of taipan and educational outreach is crucial. Proper husbandry antivenom across the venoms of all Oxyuranus practices are a must for ensuring the health of and Pseudonaja species. In addition, to ascertain any institution’s collection. In addition to concerns differences in venom biochemistry that influence associated with animal health, numerous daily antivenom efficacy variation, we tested for relative activities associated with the routine care and cofactor dependence. We found that the new ICP maintenance of a venomous collection can pose taipan antivenom exhibited high selectivity for significant risks to employee safety. -

Popular Names for Bushmaster (Lachesis Muta) and Lancehead

Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical Journal of the Brazilian Society of Tropical Medicine Vol.:52:e-20180140, 2019 doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0140-2018 Short Communication Popular names for bushmaster (Lachesis muta) and lancehead (Bothrops atrox) snakes in the Alto Juruá region: repercussions for clinical-epidemiological diagnosis and surveillance Ageane Mota da Siva[1, 2], Wuelton Marcelo Monteiro[3, 4] and Paulo Sérgio Bernarde[2,5] [1]. Instituto Federal do Acre, Campus de Cruzeiro do Sul, Cruzeiro do Sul, AC, Brasil. [2]. Programa de Pós-Graduação Bionorte – Universidade Federal do Acre – UFAC, Rio Branco, Acre, Brasil. [3]. Fundação de Medicina Tropical Dr. Heitor Vieira Dourado, Manaus, AM, Brasil. [4]. Universidade do Estado do Amazonas, Manaus, AM, Brasil. [5]. Laboratório de Herpetologia, Centro Multidisciplinar, Campus Floresta, Universidade Federal do Acre, Cruzeiro do Sul, AC, Brasil. Abstract Introduction: The popular names “surucucu” and “jararaca” have been used in literature for Lachesis muta and Bothrops atrox snakes, respectively. We present the popular names reported by patients who suffered snakebites in the Alto Juruá region. Methods: Fifty-seven (76%) patients saw the snakes that caused the envenomations and were asked about their popular names and sizes. Results: The snakes Bothrops atrox, referred to as “jararaca,” were recognized as being mainly juveniles (80.7%) and “surucucu” as mainly adults (81.8%). Conclusions: The name “surucucu” is used in the Alto Juruá region for the snake B. atrox, mainly for adult specimens. Keywords: Snakebites. Ophidism. Venomous snakes. Amazonia. State of Acre. The bushmaster (Lachesis muta) is the largest venomous The rarity of this species is also reflected in the few existing snake in South America, at over three meters in length. -

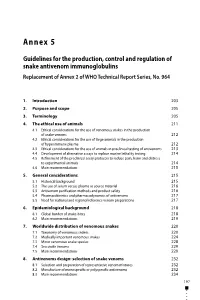

Guidelines for the Production, Control and Regulation of Snake Antivenom Immunoglobulins Replacement of Annex 2 of WHO Technical Report Series, No

Annex 5 Guidelines for the production, control and regulation of snake antivenom immunoglobulins Replacement of Annex 2 of WHO Technical Report Series, No. 964 1. Introduction 203 2. Purpose and scope 205 3. Terminology 205 4. The ethical use of animals 211 4.1 Ethical considerations for the use of venomous snakes in the production of snake venoms 212 4.2 Ethical considerations for the use of large animals in the production of hyperimmune plasma 212 4.3 Ethical considerations for the use of animals in preclinical testing of antivenoms 213 4.4 Development of alternative assays to replace murine lethality testing 214 4.5 Refinement of the preclinical assay protocols to reduce pain, harm and distress to experimental animals 214 4.6 Main recommendations 215 5. General considerations 215 5.1 Historical background 215 5.2 The use of serum versus plasma as source material 216 5.3 Antivenom purification methods and product safety 216 5.4 Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of antivenoms 217 5.5 Need for national and regional reference venom preparations 217 6. Epidemiological background 218 6.1 Global burden of snake-bites 218 6.2 Main recommendations 219 7. Worldwide distribution of venomous snakes 220 7.1 Taxonomy of venomous snakes 220 7.2 Medically important venomous snakes 224 7.3 Minor venomous snake species 228 7.4 Sea snake venoms 229 7.5 Main recommendations 229 8. Antivenoms design: selection of snake venoms 232 8.1 Selection and preparation of representative venom mixtures 232 8.2 Manufacture of monospecific or polyspecific antivenoms 232 8.3 Main recommendations 234 197 WHO Expert Committee on Biological Standardization Sixty-seventh report 9.