Confusion at the National Labor Relations Board: the Im Sapplication of Board Precedent to Resolve the Yale University Grade-Strike Stephen L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Men's Basketball Coaching Records

MEN’S BASKETBALL COACHING RECORDS Overall Coaching Records 2 NCAA Division I Coaching Records 4 Coaching Honors 31 Division II Coaching Records 36 Division III Coaching Records 39 ALL-DIVISIONS COACHING RECORDS Some of the won-lost records included in this coaches section Coach (Alma Mater), Schools, Tenure Yrs. WonLost Pct. have been adjusted because of action by the NCAA Committee 26. Thad Matta (Butler 1990) Butler 2001, Xavier 15 401 125 .762 on Infractions to forfeit or vacate particular regular-season 2002-04, Ohio St. 2005-15* games or vacate particular NCAA tournament games. 27. Torchy Clark (Marquette 1951) UCF 1970-83 14 268 84 .761 28. Vic Bubas (North Carolina St. 1951) Duke 10 213 67 .761 1960-69 COACHES BY WINNING PERCENT- 29. Ron Niekamp (Miami (OH) 1972) Findlay 26 589 185 .761 1986-11 AGE 30. Ray Harper (Ky. Wesleyan 1985) Ky. 15 316 99 .761 Wesleyan 1997-05, Oklahoma City 2006- (This list includes all coaches with a minimum 10 head coaching 08, Western Ky. 2012-15* Seasons at NCAA schools regardless of classification.) 31. Mike Jones (Mississippi Col. 1975) Mississippi 16 330 104 .760 Col. 1989-02, 07-08 32. Lucias Mitchell (Jackson St. 1956) Alabama 15 325 103 .759 Coach (Alma Mater), Schools, Tenure Yrs. WonLost Pct. St. 1964-67, Kentucky St. 1968-75, Norfolk 1. Jim Crutchfield (West Virginia 1978) West 11 300 53 .850 St. 1979-81 Liberty 2005-15* 33. Harry Fisher (Columbia 1905) Fordham 1905, 16 189 60 .759 2. Clair Bee (Waynesburg 1925) Rider 1929-31, 21 412 88 .824 Columbia 1907, Army West Point 1907, LIU Brooklyn 1932-43, 46-51 Columbia 1908-10, St. -

2010-11 NCAA Men's Basketball Records

Coaching Records All-Divisions Coaching Records ............... 2 Division I Coaching Records ..................... 3 Division II Coaching Records .................... 24 Division III Coaching Records ................... 26 2 ALL-DIVISIONS COACHING RECORDS All-Divisions Coaching Records Some of the won-lost records included in this coaches section have been Coach (Alma Mater), Schools, Tenure Yrs. Won Lost Pct. adjusted because of action by the NCAA Committee on Infractions to forfeit 44. Don Meyer (Northern Colo. 1967) Hamline 1973-75, or vacate particular regular-season games or vacate particular NCAA tourna- Lipscomb 76-99, Northern St. 2000-10 ........................... 38 923 324 .740 ment games. The adjusted records for these coaches are listed at the end of 45. Al McGuire (St. John’s [NY] 1951) Belmont Abbey the longevity records in this section. 1958-64, Marquette 65-77 .................................................... 20 405 143 .739 46. Jim Boeheim (Syracuse 1966) Syracuse 1977-2010* ..... 34 829 293 .739 47. David Macedo (Wilkes 1996) Va. Wesleyan 2001-10* ... 10 215 76 .739 48. Phog Allen (Kansas 1906) Baker 1906-08, Haskell 1909, Coaches by Winning Percentage Central Mo. 13-19, Kansas 08-09, 20-56 .......................... 48 746 264 .739 49. Emmett D. Angell (Wisconsin) Wisconsin 1905-08, (This list includes all coaches with a minimum 10 head coaching seasons at NCAA Oregon St. 09-10, Milwaukee 11-14 ................................. 10 113 40 .739 schools regardless of classification.) 50. Everett Case (Wisconsin 1923) North Carolina St. 1947-65 ................................................... 19 377 134 .738 Coach (Alma Mater), Schools, Tenure Yrs. Won Lost Pct. * active; # Keogan’s winning percentage includes three ties. 1. Clair Bee (Waynesburg 1925) Rider 1929-31, Long Island 32-43, 46-51 ...................................................... -

The NCAA News, Rep

The NCAA Official Publication of the National Collegiate Athletic Association March 13,1991, Volume 28 Number 11 Division I commissioners back enforcement process Commissioners of the nation’s ident Thomas E. Yeager, commis- whelmingly supports the NCAA’s port for the NCAA’s program. The NCAA enforcement pro- Division I athletics conferences an- sioner of the Colonial Athletic process and the penalties that have “Accordingly, the commissioners gram and procedures have been nounced March 13 their strong en- Association, in forwarding the state- been levied. Unfortunately, repre- believed it was time to make a commended and supported by the dorsement of the NCAA enforce- ment to NCAA Executive Director sentatives of institutions found to statement supporting the NCAA’s Collegiate Commissioners Associa- ment program. Richard D. Schultz, said: have committed violations often process and reminding the mem- tion and University Commissioners The joint announcement was “The members of the Collegiate criticize the Association and its bership and the public that the Association, the organizations of made by the Collegiate Commis- Commissioners Association and Uni- procedures in an attempt to con- NCAA is a body of institutions, and the chief executive officers of the sioners Association and University versity Commissioners Association vince their fans that they are de- it is the constant element in the nation’s major-college conferences. Commissioners Association, which wished to express their disagreement fending the institution against the athletics program-the institu- The commissioners noted the com- represent all of the 36 conferences in with criticism of the NCAA cn- charges, regardless of whether those tion- that must be held accounta- plaints most often assertions that Division I of the NCAA. -

Through the Decades

New ’50s ’60s ’70s ’80s 1990s ’00s ’10s Era THROUGH ACC Basketball THE DECADES Visit JournalNow.com for more content on the history of ACC men’s basketball. — Compiled by Dan Collins GREATEST HITS Duke 104, Kentucky 103 (OT): March 28, 1992, Wake Philadelphia Forest’s Christian Laettner snagged Grant Hill’s 70-foot pass, Tim Duncan turned and hit the shot heard around the sporting world. The victory in the championship game of the East Re- gional kept Coach Mike Krzyzewski’s Blue Devils marching ALL- inexorably to their second consecutive national title. Wake Forest 82, UNC 80 (OT): March 12, DECADE 1995, Greensboro With one floating 10-foot jumper, Randolph Chil- TEAM dress lifted the Deacons to their first ACC title in 33 G Randolph Childress, seasons and broke the record for points in an ACC Wake Forest Tournament that had stood since 1957. Childress Second-team consensus made 12 of 22 shots from the floor and 9 of 17 from All-America 1995; first-team 3-point range, including one infamous basket over All-ACC 1994, 1995 and sec- Jeff McInnis after his crossover dribble left McInnis ond-team 1993; first-team sprawled on the Greensboro Coliseum floor. All-ACC Tournament 1994, AP PHOTO 1995; Everett Case Award PHOTO AP 1995 Christian Laettner’s Randolph Childress’ winning shot winning shot G Grant Hill, Duke against Kentucky against UNC First-team consensus All- America 1994 and second- team 1993; ACC player of the year 1994; first-team All-ACC 1993, 1994 and second-team 1992; second-team All-ACC COACH Tournament 1991, 1992, 1994 QUOTES OF THE DECADE OF THE F Antawn Jamison, UNC “When the press asked me over the years about my “It seems like every team wants to beat Carolina for National player of the retirement plans, I told them the truth, which was that I some reason. -

2021-01-31Smu

This Game Next Game: Head Coach ..........................................Tim Jankovich NABC Coaches vs Cancer SMU Mustangs Overall ...........................................256-173 (14th Year) #SuitsAndSneakers at TULSA Golden Hurricane At SMU.................................................99-52 (5th Year) Wednesday, Feb. 3 - 8pm CT Location (Enrollment) ..................Dallas, Texas (12,385) SMU Mustangs Tulsa, Oklahoma (9-3, 5-3 American) Reynolds Center Conference..........................................American Athletic at TV: ESPNU Colors............................................................Red & Blue [6/6] HOUSTON SMU Radio: KAAM 770 AM Arena ...........................Moody Coliseum (7,000 / 1,800) (14-1, 9-1 American) TuneIn App - SMU, SMU App Court ..............................................David B. Miller Court (Rich Phillips, Scott Garner) President ........................................Dr. R. Gerald Turner Sunday, January 31 - 12pm CT #PonyUp Director of Athletics ..........................................Rick Hart Basketball SID.............Herman Hudson / [email protected] SMU Basketball Houston, Texas - Fertitta Center Following Game Office/Cell Phone ............214-768-1304 / 214-924-0358 70 All-League 1st Team Honors SMU Mustangs at ECU Pirates ................................Lindsey Olsen / [email protected] 24 Selections In The NBA Draft TV: ESPN (Kevin Brown, Jon Crispin) Monday, Feb. 8 - 5pm ET/4pm CT Web Site ..........................................SMUMustangs.com 16 Conference Titles Greenville, -

SMU Basketball 70 All-League 1St Team Honors 24 Selections in The

This Game: Next Game: Head Coach ..........................................Tim Jankovich EAST CAROLINA Pirates Overall ...........................................220-146 (12th Year) CORNELL Big Red at SMU Mustangs At SMU .............................................63-25 (Third Year) (5-6, 0-0 Ivy League) Wed., Jan. 2 - 7pm Location (Enrollment) ..................Dallas, Texas (11,789) at Dallas, Texas Conference..........................................American Athletic SMU Mustangs David B. Miller Court at Colors............................................................Red & Blue (7-4, 0-0 American) Moody Coliseum (7,000) Arena .......................................Moody Coliseum (7,000) TV: ESPN3 / Watch ESPN Court ..............................................David B. Miller Court Saturday, December 22 - 7pm SMU Radio: KAAM 770 AM TuneIn App - SMU, SMU App President ........................................Dr. R. Gerald Turner Dallas, Texas (Rich Phillips, Allen Stone) Director of Athletics ..........................................Rick Hart David B. Miller Court at Basketball SID.............Herman Hudson / [email protected] SMU Basketball Moody Coliseum (7,000) Following Game: Office/Cell Phone ............214-768-1304 / 214-924-0358 ................................Andy Lohman / [email protected] 70 All-League 1st Team Honors SMU Mustangs at TULANE Green Wave ................................Lindsey Olsen / [email protected] 24 Selections In The NBA Draft TV: ESPN3 / Watch ESPN (Dave Raymond, Stephen Howard) Fri., Jan. 4 - 6pm Web Site -

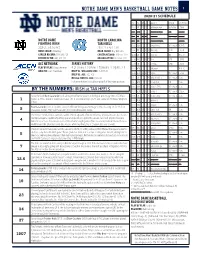

Notre Dame Men's Basketball Game Notes 1 2020-21 Schedule

NOTRE DAME MEN'S BASKETBALL GAME NOTES 1 2020-21 SCHEDULE Date Day AP C Opponent Network Time/Result 11/28 SAT 13 12 at Michigan State Big Ten Net L, 70-80 12/2 WED Western Michigan RSN canceled 12/4 FRI 13 14 Tennessee ACC Network canceled NOTRE DAME NORTH CAROLINA 12/5 SAT Purdue Fort Wayne canceled FIGHTING IRISH TAR HEELS 12/6 SUN Detroit Mercy ACC Network W, 78-70 2020-21: 3-5, 0-2 ACC 2020-21: 5-4, 0-2 ACC HEAD COACH: Mike Brey HEAD COACH: Roy Williams 12/8 TUE 22 20 & Ohio State ESPN2 L, 85-90 CAREER RECORD: 539-290 / 26 CAREER RECORD: 890-257 / 33 12/12 SAT Kentucky CBS W, 64-63 RECORD AT ND: 440-238 / 21 RECORD AT UNC: 472-156 / 18 12/16 THU 21 23 * Duke ESPN L, 65-75 ACC NETWORK SERIES HISTORY 12/19 SAT ^ vs. Purdue ESPN2 L, 78-88 PLAY BY PLAY: Doug Sherman 8-25 | Home: 3-5 | Away: 1-7 | Neutral: 4-13 | ACC: 3-8 12/23 WED Bellarmine W, 81-70 ANALYST: Cory Alexander BREY VS. WILLIAMS/UNC: 4-10/4-10 BREY VS. ACC: 102-106 12/30 WED 23 24 * Virginia ACC Network L, 57-66 ND ALL-TIME VS. ACC: 169-212 1/2 SAT * at North Carolina ACC Network 4 p.m. Full series history available on page 5 of this notes package 1/6 WED * Georgia Tech RSN 7 p.m. 1/10 SUN 24 * at Virginia Tech ACC Network 6 p.m. -

Be a Builder!

Issue 1 August M T W Th F Monthly Builders Theme: 1 2 3 6 7 8 9 10 13 14 15 16 17 Be A Builder! 20 21 22 23 24 27 28 29 30 31 Builders I saw them tearing a building down, What builders have taken years to do.” A gang of men in a busy town. So I asked myself, as I went my way, August 3rd With a ‘yo heave ho’ and a lusty yell, Which of these roles am I to play? Uniform Resale They swung a beam and the sidewall fell. Am I the builder, who works with care, I asked the foreman if these men were as skilled Measuring life by the rule and square; 6:00pm – 8:00pm As those he would hire if he were to build. Or am I the wrecker who walks the town, He laughed and said, “Oh, no indeed, Content in the role of tearing down? August 4th Common labor is all I need, I’ve made my decision; I’ll start today, Uniform Resale For they can wreck in a day or two, I’ll be a builder in every way! 11:00am – 2:00pm Summer Office Hours: August 15th Monday – Thursday 9:00am – 1:00pm Senior Orientation Friday CLOSED 12:00pm New Volunteer Procedures August 16th If you would like to volunteer at APA this year we ask that you please come in on Back to School Night to learn about the new Nevada state requirements for volunteers. This Secondary Orientation includes fingerprinting and background clearances. -

Combined Guide for Web.Pdf

2015-16 American Preseason Player of the Year Nic Moore, SMU 2015-16 Preseason Coaches Poll Preseason All-Conference First Team (First-place votes in parenthesis) Octavius Ellis, Sr., F, Cincinnati Daniel Hamilton, So., G/F, UConn 1. SMU (8) 98 *Markus Kennedy, R-Sr., F, SMU 2. UConn (2) 87 *Nic Moore, R-Sr., G, SMU 3. Cincinnati (1) 84 James Woodard, Sr., G, Tulsa 4. Tulsa 76 5. Memphis 59 Preseason All-Conference Second Team 6. Temple 54 7. Houston 48 Troy Caupain, Jr., G, Cincinnati Amida Brimah, Jr., C, UConn 8. East Carolina 31 Sterling Gibbs, GS, G, UConn 9. UCF 30 Shaq Goodwin, Sr., F, Memphis 10. USF 20 Shaquille Harrison, Sr., G, Tulsa 11. Tulane 11 [*] denotes unanimous selection Preseason Player of the Year: Nic Moore, SMU Preseason Rookie of the Year: Jalen Adams, UConn THE AMERICAN ATHLETIC CONFERENCE Table Of Contents American Athletic Conference ...............................................2-3 Commissioner Mike Aresco ....................................................4-5 Conference Staff .......................................................................6-9 15 Park Row West • Providence, Rhode Island 02903 Conference Headquarters ........................................................10 Switchboard - 401.244-3278 • Communications - 401.453.0660 www.TheAmerican.org American Digital Network ........................................................11 Officiating ....................................................................................12 American Athletic Conference Staff American Athletic Conference Notebook -

The History of Texas High School Basketball Volume IV 1983-1984

The History of Texas High School Basketball Volume IV 1983-1984 By Mark McKee Website www.txhighschoolbasketball.com Contents Perface 4 Acknowledgements 5 AAAAA 1983 6 AAAA 1983 89 AAA 1983 107 AA 1983 115 A 1983 123 AAAAA 1984 125 AAAA 1984 211 AAA 1984 235 AA 1984 243 A 1984 248 Preface History of Texas High School Basketball Volume IV By Mark McKee By 1982 my brother-in-law was no longer able to attend the state tournament and I went with a coaching friend. The old Stephen F. Austin Hotel, where I stayed for the first five years at the tournament was remodeled and renamed. The cost became outrageous there, so we no longer enjoyed staying downtown. Today the Hotel is called InterContinental Stephen F. Austin. Visiting Sixth street became popular and I continued to eat at the Waterloo Ice House. The main attraction in those days was playing at Gregory Gym on the campus of U.T. We always had great pickup games at the student activity center, located right next to Gregory. Jogging was also another passion of mine. Town Lake provided great running trails just south of downtown Austin. Coaching clinics became the norm, as I continued to learn the game. Great times. The person who had the greatest impact on my life was my brother-in-law. This book is dedicated to him. At the age of 10, he began coming over to the house dating my older sister. He was like a family member. For the next twenty years he influenced all aspects of my life. -

2015 Monarch Basketball

2014 - 2015 MONARCH BASKETBALL #1 OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY (27-7) in NATIONAL INVITATION TOURNAMENT MARCH 31, 2015 | 9:00 PM | MADISON SQUARE GARDEN (STANFORD/TEMPLE/MIAMI) MONARCH PROBABLE STARTERS MONARCH 2014-15 SCHEDULE G 1 Aaron Bacote, 6-4 Jr, Hampton, VA., 10.1 ppg/3.1 rpg Mon. Nov 10 Mount Olive (Exhibition) 7:00 p.m. W, 76-61 Sat. Nov 15 UNC Wilmington 7:00 p.m. W, 76-56 G 0 Jordan Baker , 6-2, So., Hampton, VA., 4.1 ppg/2.2 apg Tue. Nov 18 Richmond 8:00 p.m. W, 63-57 G 20 Trey Freeman, 6-2, Jr. Virginia Beach, VA., 17.0 ppg/3.6 apg Fri. Nov 21 LSU% 6:30 p.m. W, 70-61 F 35 Jonathan Arledge, 6-9, Gr. Silver Spring, MD., 8.9 ppg./4.9 rpg Sun. Nov 23 Illinois State 10:00 p.m. L, 45-64 Mon. Nov 24 Gardner-Webb% 6:30 p.m. W, 58-46 F 21 Denzell Taylor, 6-7, So., Ontario, Canada, 3.0 ppg/6.0 rpg Sat. Nov 29 #14 VCU 2:00 p.m. W, 73-67 MONARCH RESERVES Wed. Dec 03 George Mason 7:30 p.m. W, 75-69 Sun. Dec 14 NC A&T 2:00 p.m. W, 85-48 G 3 Keenan Palmore, 6-1, Jr. Stone Mountain, GA., 2.6 ppg/1.5 rpg Wed. Dec 17 Georgia State 8:00 p.m. W, 58-54 Fri. Dec 19 Maryland - Eastern Shore 7:00 p.m. W, 60-43 F 23 Richard Ross, 6-6, Sr. -

2017-18 Men's Basketball

2017-18 MEN’S BASKETBALL RECORD BOOK 2017-18 Men’s Basketball Record Book Western Athletic Conference TABLE OF CONTENTS 9250 E. Costilla Ave., Suite 300 Englewood, CO 80112-3662 2016-17 Statistics ................................2-13 Phone: (303) 799-9221 FAX: (303) 799-3888 WAC Team Records ..............................14-15 Top 25 Rankings ......................................16 WAC STAFF DIRECTORY WAC Individual Records .......................17-18 Non-Conference Records ...........................19 Jeff Hurd, Commissioner .............................................................(303) 962-4216 ............ [email protected] Mollie Lehman, Senior Associate Commissioner and CFO ...............(303) 962-4215 [email protected] Attendance ..............................................19 David Chaffin, Assoc. Commissioner of Technology & Conference Svcs. .. (303) 962-4212 ........ [email protected] Career Records ....................................20-22 Marlon Edge, Assistant Commissioner of Compliance .....................(303) 962-4211 .......... [email protected] Single-Season Top 15 ..........................23-26 Vicky Eggleston, Assistant Commissioner of Creative Services ...........(303) 962-4207 [email protected] Yearly Team Leaders.............................27-32 Hope Shuler, Assistant Commissioner of Media Relations ...............(303) 962-4213 ......... [email protected] Yearly Individual Leaders ......................33-38 Eric Danner, Executive Producer of WAC Digital Network ................(303) 962-4203 .......