Translating a Poetic Discourse: Modern Poetry of Pakistan Reviewed by Qaisar Abbas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Muhammad Umar Memon Bibliographic News

muhammad umar memon Bibliographic News Note: (R) indicates that the book is reviewed elsewhere in this issue. Abbas, Azra. ìYouíre Where Youíve Always Been.î Translated by Muhammad Umar Memon. Words Without Borders [WWB] (November 2010). [http://wordswithoutborders.org/article/youre-where-youve-alwaysbeen/] Abbas, Sayyid Nasim. ìKarbala as Court Case.î Translated by Richard McGill Murphy. WWB (July 2004). [http://wordswithoutborders.org/article/karbala-as-court-case/] Alam, Siddiq. ìTwo Old Kippers.î Translated by Muhammad Umar Memon. WWB (September 2010). [http://wordswithoutborders.org/article/two-old-kippers/] Alvi, Mohammad. The Wind Knocks and Other Poems. Introduction by Gopi Chand Narang. Selected by Baidar Bakht. Translated from Urdu by Baidar Bakht and Marie-Anne Erki. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi, 2007. 197 pp. Rs. 150. isbn 978-81-260-2523-7. Amir Khusrau. In the Bazaar of Love: The Selected Poetry of Amir Khusrau. Translated by Paul Losensky and Sunil Sharma. New Delhi: Penguin India, 2011. 224 pp. Rs. 450. isbn 9780670082360. Amjad, Amjad Islam. Shifting Sands: Poems of Love and Other Verses. Translated by Baidar Bakht and Marie Anne Erki. Lahore: Packages Limited, 2011. 603 pp. Rs. 750. isbn 9789695732274. Bedi, Rajinder Singh. ìMethun.î Translated by Muhammad Umar Memon. WWB (September 2010). [http://wordswithoutborders.org/article/methun/] Chughtai, Ismat. Masooma, A Novel. Translated by Tahira Naqvi. New Delhi: Women Unlimited, 2011. 152 pp. Rs. 250. isbn 978-81-88965-66-3. óó. ìOf Fists and Rubs.î Translated by Muhammad Umar Memon. WWB (Sep- tember 2010). [http://wordswithoutborders.org/article/of-fists-and-rubs/] Granta. 112 (September 2010). -

Fahmida Riaz - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Fahmida Riaz - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Fahmida Riaz(28 July 1946) Fahmida Riaz (Urdu: ?????? ????) is a well known Urdu writer, poet, and feminist of Pakistan. Along with Zehra Nigah, Parveen Shakir, Kishwar Naheed , Riaz is amongst the most prominent female Urdu poets in Pakistan. She is author of Godaavari, Khatt-e Marmuz, and Khana e Aab O Gil, the first translation of the Masnavi of Maulana Jalaluddin Rumi from Farsi into Urdu she has also translated the works of Shah Abdul Latif Bhitai and Shaikh Ayaz from Sindhi to Urdu. <b> Early Life </b> Fahmida Riaz was born on July 28, 1946 in a literary family of Meerut, UP, India. Her father, Riaz-ud-Din Ahmed, was an educationist, who had a great influence in mapping and establishing modern education system for Sindh. Her family settled in Hyderabad following her father's transfer to Sindh. Fahmida learnt Urdu, and Sindhi language literature in childhood and later Persian. Her early life was marked by the loss of her father when she was just 4 years old. She was already making poetry at this young age. Her mother (Husna Begum) supported the family unit through entrepreneurial efforts until Fahmida entered college, when she started work as a newscaster for Radio Pakistan. Fahmida's first poetry collection was written at this time. <b> Family and Work </b> She was persuaded by family to enter into an arranged marriage after graduation from college, and spent a few years in the UK with her first husband before returning to Pakistan after a divorce. -

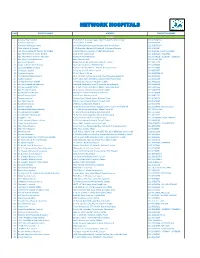

Network Hospitals

NETWORK HOSPITALS S.NO HOSPITAL NAME ADDRESS CONTACT NUMBERS KARACHI 1 Adamjee Eye Hospital 39-B, Block C, Adamjee Nagar, Opp. Zubaida Hospital, Dhoraji 021-34132824-6 2 Advanced Eye Clinic 17-C/1, Block 6, PECHS 021-34540999 3 Advanced Radiology Centre Behind Hamdard University Hospital, M.A. Jinnah Road 021-32783535-6 4 Afsar Memorial Hospital B-35 Khalid Bin Waleed Rd, Sector W, Gulshan-e-Maymar 021-36353124 5 Aga Khan Hospital for Women Karimabad Ayesha Manzil, at junction of Shahrah-e-Pakistan 021-3682296-3 / 021-33100006 6 Aga Khan Maternity Home Garden Gold Street, Garden East 021-33100005 / 32256903 7 Aga Khan Maternity Home Kharadar Atmaram Pritamdas Road 021-32524618 / 32542187 / 33100007 8 Aga Khan University Hospital Main Stadium Road 021 111-911-911 9 Akhter Eye Hospital Rashid Minhas Rd, 4/C Block 5 Gulshan-e-Iqbal 021-34811979 10 Al Ain Institute of Eye Disease Shahrah-e-Quaideen, PECHS Block 2 021-34556460 11 Al Hadeed Medical Centre Gulshan e Hadeed Phase 1 Phase 1 Bin Qasim Town 021-34713800 12 Al Rayyaz Hospital St-24, Sector 11/B, North Karachi 021-36907697 13 Altamash Hospital ST 9A / Block 1, Clifton 021-35187000-16 14 Arif Defence Medical Centre DK-1, Off 34th Commercial Street, Main Khayaban-e-Bukhari 021-35155631 15 Asghar Hospital KDA Market, KDA roundabout, Block B North Nazimabad 021-36642389 16 Ashfaq Memorial Hospital University Rd, Block 13 C Gulshan-e-Iqbal 021-34822261 17 Asif Eye Hospital Bahadarabad Westland Apartment, Ismail Chowrangi, Bahadurabad 021-34944530 18 Asif Eye Hospital Clifton 65-C, 24th Commercial Street, Phase II Extension, DHA 021-35385166 19 Atia General Hospital 48-A, Darakhshan Society, Kala Board, Malir 021-34400726 20 Ayesha General Hospital Gulshan-e- Hadeed C-50 Phase -3 Side Rd 021 34716608 21 Azam Town Hospital Azam Town, Mehmoodabad 021-35801741 22 Banaras Hospital Banaras Bazar Chowk, Sector 8 Orangi Town, 021-34150416 23 Bay View Hospital 205 A-ll, Saba Avenue, Zone A Phase 8, DHA 021-35246225 24 Boulevard Hospital 17th East Street, D.H.A. -

Ishrat Afreen - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Ishrat Afreen - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Ishrat Afreen(25 December 1956) Ishrat Afreen (Urdu: ???? ?????; Hindi: ???? ?????; alternative spelling: Ishrat Aafreen; born December 25, 1956) is an Urdu poet and women's rights activist named one of the five most influential and trend-setting female voices in Urdu Literature. Her works have been translated in many languages including English, Japanese, Sanskrit and Hindi. The renowned ghazal singers Jagjit Singh & Chitra Singh also performed her poetry in their anthology, Beyond Time (1987). Famed actor Zia Mohyeddin also recites her nazms in his 17th and 20th volumes as well as his ongoing concerts. <b> Early Life and Career </b> Ishrat Jehan was born into an educated family in Karachi, Pakistan as the oldest of five children. She later took the pen name Ishrat Afreen. She was first published at the age of 14 in the Daily Jang on April 31, 1971. She continued writing and was published in a multitude of literary magazines across the subcontinent of India and Pakistan. She eventually became assistant editor for the monthly magazine Awaaz, edited by the poet Fahmida Riaz. Parallel to her writing career she participated in several radio shows on Radio Pakistan from 1970-1984 that aired nationally and globally. She later worked under Mirza Jamil on the now universal Noori Nastaliq Urdu script for InPage. She married Syed Perwaiz Jafri, an Indian lawyer, in 1985 and migrated to India. Five years thereafter, the couple and their two children migrated to America. They now reside in Houston, Texas with their three children. -

Literary Criticism and Literary Historiography University Faculty

University Faculty Details Page on DU Web-site (PLEASE FILL THIS IN AND Email it to [email protected] and cc: [email protected]) Title Prof./Dr./Mr./Ms. First Name Ali Last Name Javed Photograph Designation Reader/Associate Professor Department Urdu Address (Campus) Department of Urdu, Faculty of Arts, University of Delhi, Delhi-7 (Residence) C-20, Maurice Nagar, University of Delhi, Delhi-7 Phone No (Campus) 91-011-27666627 (Residence)optional 27662108 Mobile 9868571543 Fax Email [email protected] Web-Page Education Subject Institution Year Details Ph.D. JNU, New Delhi 1983 Thesis topic: British Orientalists and the History of Urdu Literature Topic: Jaafer Zatalli ke Kulliyaat ki M.Phil. JNU, New Delhi 1979 Tadween M.A. JNU, New Delhi 1977 Subjects: Urdu B.A. University of Allahabad 1972 Subjects: English Literature, Economics, Urdu Career Profile Organisation / Institution Designation Duration Role Zakir Husain PG (E) College Lecturer 1983-98 Teaching and research University of Delhi Reader 1998 Teaching and research National Council for Promotion of Director April 2007 to Chief Executive Officer of the Council Urdu Language, HRD, New Delhi December ’08 Research Interests / Specialization Research interests: Literary criticism and literary historiography Teaching Experience ( Subjects/Courses Taught) (a) Post-graduate: 1. History of Urdu Literature 2. Poetry: Ghalib, Josh, Firaq Majaz, Nasir Kazmi 3. Prose: Ratan Nath Sarshar, Mohammed Husain Azad, Sir Syed (b) M. Phil: Literary Criticism Honors & Awards www.du.ac.in Page 1 a. Career Awardee of the UGC (1993). Completed a research project entitled “Impact of Delhi College on the Cultural Life of 19th Century” under the said scheme. -

Ajeeb Aadmi—An Introduction Ismat Chughtai, Sa'adat Hasan Manto

Ajeeb Aadmi—An Introduction I , Sa‘adat Hasan Manto, Krishan Chandar, Rajinder Singh Bedi, Kaifi Azmi, Jan Nisar Akhtar, Majrooh Sultanpuri, Ali Sardar Jafri, Majaz, Meeraji, and Khawaja Ahmed Abbas. These are some of the names that come to mind when we think of the Progressive Writers’ Movement and modern Urdu literature. But how many people know that every one of these writers was also involved with the Bombay film indus- try and was closely associated with film directors, actors, singers and pro- ducers? Ismat Chughtai’s husband Shahid Latif was a director and he and Ismat Chughtai worked together in his lifetime. After Shahid’s death Ismat Chughtai continued the work alone. In all, she wrote scripts for twelve films, the most notable among them ◊iddµ, Buzdil, Sån® kµ ≤µ∞y≥, and Garm Hav≥. She also acted in Shyam Benegal’s Jun∑n. Khawaja Ahmed Abbas made a name for himself as director and producer for his own films and also by writing scripts for some of Raj Kapoor’s best- known films. Manto, Krishan Chandar and Bedi also wrote scripts for the Bombay films, while all of the above-mentioned poets provided lyrics for some of the most alluring and enduring film songs ever to come out of India. In remembering Kaifi Azmi, Ranjit Hoskote says that the felicities of Urdu poetry and prose entered the consciousness of a vast, national audience through the medium of the popular Hindi cinema; for which masters of Urdu prose, such as Sadat [sic] Hasan Manto, wrote scripts, while many of the Progressives, Azmi included, provided lyrics. -

Hafeez Jalandhari - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Hafeez Jalandhari - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Hafeez Jalandhari(14 January 1900 - 21 December 1982) Abu-Al-Asar Hafeez Jalandhari (Urdu: ??? ????? ???? ????????) Pakistani writer, poet and, above all, composer of the National Anthem of Pakistan. He was born in Jalandhar, Punjab, British India on January 14, 1900. After independence of Pakistan in 1947, Hafeez Jalandhari moved to Lahore. Hafeez made up for the lack of formal education with self-study but he has the privilege to have some advise from the great Persian poet Maulana Ghulam Qadir Bilgrami. His dedication, hard work and advise from such a learned person carved his place in poetic pantheon. Hafeez Jalandhari actively participated in Pakistan Movement and used his writings to propagate for the cause of Pakistan. In early 1948, he joined the forces for the freedom of Kashmir and got wounded. Hafeez Jalandhari wrote the Kashmiri Anthem, "Watan Hamara Azad Kashmir". He wrote many patriotic songs during Pakistan, India war in 1965. Hafeez Jalandhari served as Director General of morals in Pakistan Armed Forces, and very prominent position as adviser to the President, Field Marshal Mohammad Ayub Khan and also Director of Writer's Guild. Hafeez Jalandhari's monumental work of poetry, Shahnam-e-Islam, gave him incredible fame which, in the manner of Firdowsi's Shahnameh, is a record of the glorious history of Islam in verse. Hafeez Jalandhari wrote the national anthem of Pakistan composed by Ahmed Ghulamali Chagla also known as Ahmed G Chagla. He is unique in Urdu poetry for the enchanting melody of his voice and lilting rhythms of his songs and lyrics. -

KLF-10 Programme 2019

Friday, 1 March 2019 Inauguration of the 10th Karachi Literature Festival Main Garden, Beach Luxury Hotel, Karachi 5.00 p.m. Arrival of Guests 5.30 p.m. Welcome Speeches by Festival Organizers 5.45 p.m. Speech by the Chief Guest: Honourable Governor Sindh, Imran Ismail Speeches by: Mark Rakestraw, Deputy Head of Mission, BDHC, Didier Talpain, Consul General of France, Enrico Alfonso Ricciardi, Deputy Head of Mission, Italian Consulate 6.00 p.m. Karachi Literature Festival-Infaq Foundation Best Urdu Literature Prize 6.05 p.m. Keynote Speeches by Zehra Nigah and Muneeza Shamsie 6.45 p.m. KLF Recollection Documentary 7.00 p.m. Aao Humwatno Raqs Karo: Performance by Sheema Kermani 7.45–8.45 p.m. Panel Discussions 9.00–9.30 p.m. Safr-e-Pakistan: Pakistan’s Travelogue in String Puppets by ThespianzTheatre MC: Ms Sidra Iqbal 7.45 p.m. – 8.45 p.m. Pakistani Cinema: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow Yasir Hussain, Munawar Saeed, Nabeel Qureshi, Asif Raza Main Garden Mir, Fizza Ali Meerza, and Satish Anand Moderator: Ahmed Shah Documentary: Qalandar Code: Rise of the Divine Jasmine Feminine Atiya Khan, David C. Heath, and Syed Mehdi Raza Shah Subzwari Moderator: Arieb Azhar Aquarius Voices from Far and Near: Poetry in English Adrian Husain, Arfa Ezazi, Farida Faizullah, Room 007 Ilona Yusuf, Jaffar Khan, Moeen Faruqi, and Shireen Haroun Moderator: Salman Tarik Kureshi Book Discussion: The Begum: A Portrait of Ra’ana Liaquat Ali Khan by Deepa Agarwal and Tahmina Aziz Princess Akbar Liaquat Ali Khan and Javed Aly Khan Moderator: Muneeza Shamsie Saturday, 2 March 2019 Hall Sponsor Main Garden Jasmine Aquarius Room 007 Princess 11 a.m. -

Dr. Ambreen Tabassum Shakir Jan, Assistant Professor

Dr. Ambreen Tabassum Shakir Jan, Assistant Professor 1. PERSONAL INFORMATION Name Ambreen Tabassum Shakir Jan Father's Name Muhamad Rafique NIC No. 17301-3818022-6 Domicile Peshawar Date of Birth 01.03.1975 Marital Status Married Religion Islam Mobile No/PTCL No 0300-9191864, 051-9268330 Address PAF Falcon Complex, I.H. 131, Street No. 19, Expressway, Rawalpindi. 2. PROFESSIONAL INFORMATION Designation: Assistant Professor Department Urdu University: National University of Modern Languages, H-9, Islamabad. Phone (office): +92-51-9265100-110 EXT: 2261 Email: [email protected] 3. QUALIFICATIONS Discipline Certificate Degree Passing Year Board/University /Subject PhD Urdu Lit 18th July, 2011 NUML, Islamabad M.Phil/MS Urdu Lit 2009 AIOU, Islamabad Masters Urdu Lit 2005 Peshawar University Bachelors Arts 2002 F.G. College Peshawar FA/FSc Arts 2000 Peshawar Board Matric Science 1991 Peshawar Board 4. TEACHING EXPERIENCE Regular/ Designation/Post From To Organization Contract Assistant Professor November, Till date Regular Urdu Department, NUML (BPS-19) 2011 Lecturer (BPS-18) 26.9.2007 November, 2011 Regular Urdu Department, NUML Lecturer (BPS-17) 03.01.2006 25.09.2007 Regular Urdu Department, NUML Lecturer 2.5.2005 02.01.2006 Contract Urdu Department, NUML Visiting Professor i. Allama Iqbal Open University Islamabad (M.A, Urdu Literature) ii. Federal Urdu University Islamabad (MBA, Urdu Literature) Page 1of 6 5. RESEARCH PUBLICATIONS (HEC APPROVED) Sr. Topic Name of Journal Year HEC Approved No PP: 77-86 Tanhai Kay Soou Saal Aur “Daryaft” Shouba Urdu ISSN: 1814-2885 1. HEC Approved Gaiberial Garshia Markez Numl Islamabad. Vol: 20 July-Dec 2018 PP: 48-58 Faiz Ahmed Faiz Ki Shairi “ADRAAK” Shouba ISSN:2412-6144 2. -

Conferment of Pakistan Civil Awards - 14Th August, 2020

F. No. 1/1/2020-Awards-I GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN CABINET SECRETARIAT (CABINET DIVISION) ***** PRESS RELEASE CONFERMENT OF PAKISTAN CIVIL AWARDS - 14TH AUGUST, 2020 On the occasion of Independence Day, 14th August, 2020, the President of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan has been pleased to confer the following ‘Pakistan Civil Awards’ on citizens of Pakistan as well as Foreign Nationals for showing excellence and courage in their respective fields. The investiture ceremony of these awards will take place on Pakistan Day, 23rd March, 2021:- S. No. Name of Awardee Field 1 2 3 I. NISHAN-I-IMTIAZ 1 Mr. Sadeqain Naqvi Arts (Painting/Sculpture) 2 Prof. Shakir Ali Arts (Painting) 3 Mr. Zahoor ul Haq (Late) Arts (Painting/ Sculpture) 4 Ms. Abida Parveen Arts (Singing) 5 Dr. Jameel Jalibi Literature Muhammad Jameel Khan (Late) (Critic/Historian) (Sindh) 6 Mr. Ahmad Faraz (Late) Literature (Poetry) (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) II. HILAL-I-IMTIAZ 7 Prof. Dr. Anwar ul Hassan Gillani Science (Pharmaceutical (Sindh) Sciences) 8 Dr. Asif Mahmood Jah Public Service (Punjab) III. HILAL-I-QUAID-I-AZAM 9 Mr. Jack Ma Services to Pakistan (China) IV. SITARA-I-PAKISTAN 10 Mr. Kyu Jeong Lee Services to Pakistan (Korea) 11 Ms. Salma Ataullahjan Services to Pakistan (Canada) V. SITARA-I-SHUJA’AT 12 Mr. Jawwad Qamar Gallantry (Punjab) 13 Ms. Safia (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) 14 Mr. Hayatullah Gallantry (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) 15 Malik Sardar Khan (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) 16 Mr. Mumtaz Khan Dawar (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) 17 Mr. Hayat Ullah Khan Dawar Hurmaz Gallantry (Shaheed) (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) 18 Malik Muhammad Niaz Khan (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) 19 Sepoy Akhtar Khan (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) 20 Mr. -

SUHAIL-THESIS.Pdf (347.6Kb)

Copyright by Adeem Suhail 2010 The Thesis committee for Adeem Suhail Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: The Pakistan National Alliance of 1977 APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: ________________________________________ (Syed Akbar Hyder) __________________________________________ (Kamran Asdar Ali) The Pakistan National Alliance of 1977 by Adeem Suhail, BA; BSEE Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2011 The Pakistan National Alliance of 1977 by Adeem Suhail, MA The University of Texas at Austin, 2011 SUPERVISOR: Syed Akbar Hyder Abstract This study focuses on the Pakistan National Alliance (PNA) and the movement associated with that party, in the aftermath of the 1977 elections in Pakistan. Through this study, the author addresses the issue of regionalism and its effects on politics at a National level. A study of the course of the movement also allows one to look at the problems in representation and how ideological stances merge with material conditions and needs of the country’s citizenry to articulate the desire for, what is basically, an equitable form of democracy that is peculiar to Pakistan. The form of such a democratic system of governance can be gauged through the frustrations and desires of the variety of Pakistan’s oppressed classes. Moreover, the fissures within the discourses that appear through the PNA, as well as their reassessment and analysis helps one formulate a fresh conception of resistance along different matrices of society within the country. -

Scanned Using Scannx OS16000 PC

/' \ / / SAGAR 2017-2018 CHIEF EDITORS Sundas Amer, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT Austin Charlotte Giles, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT Austin Paromita Pain, Dept, of Journalism, UT Austin ^ EDITORIAL COLLECTIVE MEMBERS Nabeeha Chaudhary, Radio-Film-Television, UT Austin Andrea Guiterrez, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT Austin Hamza Muhammad Iqbal, Comparative Literature, UT Austin Namrata Kanchan, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT Austin Kathleen Longwaters, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT Austin Daniel Ng, Anthropology, UT Austin Kathryn North, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT Austin Joshua Orme, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT Austin David St. John, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT Austin Ramna Walia, Radio-Film-Television, UT Austin WEB EDITOR Charlotte Giles & Paromita Pain PRINTDESIGNER Dana Johnson EDITORIAL ADVISORS Donald R. Davis, Jr., Director, UT South Asia Institute; Professor, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT-Austin Rachel S. Meyer, Assistant Director, UT South Asia Institute EDITORIAL BOARD Richard Barnett, Associate Professor, Dept, of History, University of Virginia Eric Lewis Beverley, Assistant Professor, Dept, of History, SUNY Stonybrook Purmma Bose, Associate Professor, Dept, of English, Indiana University-Bloomineton Laura Brueck, Assomate Professor, Asian Languages & Cultures Dept., Northwestern University Indrani Chatterjee, Dept, of History, UT-Austin uiuversiiy Lalitha Gopalan, Associate Professor, Dept, of Radio-TV-Film, UT-Austin Sumit Guha, Dept, of History, UT-Austin Kathryn Hansen, Professor Emerita, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT-Austin Barbara Harlow, Professor, Dept, of English, UT-Austin Heather Hindman, Assistant Professor, Dept, of Anthropology, UT-Austin Syed Akbar Hyder, Associate Professor, Dept, of Asian Studies, UT-Austin Shanti Kumar, Associate Professor, Dept, of Radio-Television-Film, UT-Austin Janice Leoshko, Associate Professor, Dept, of Art and Art History, UT-Austin W.