Attributing the Bixby Letter Using N-Gram Tracing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No. 14~ THEY ONLY INCREASE the STATURE of the MAN

Prepared in the Interests of Book Collecting at the The University of Michigan No. 14~ THEY ONLY INCREASE THE STATURE OF THE MAN. 1Sept 1947 A Little Dinner reminded us that we had more than two hours to for Lincoln wai t before the Lincoln At 12:01 A.M. on July Papers could be opened. 2G, 1947, the Robert Todd He proposed that we Lincoln Collection of pa might pass the time plea pers relating to his father, santly listening to some of Abraham Lincoln, was our company tell us what opened to the public. they hoped to find in the This was that moment for collection. ,..rh ich many men had Dr Evans called first on wai ted years. The faces of Carl Sandburg. With a those men grouped around gentle smile on his face, the safes which had held and in the Middle West the papers were bright ern voice familiar to all with hope or troubled Lincolnians, Mr Sandburg wi th fears and worries or announced that he would stilled to conceal emo accompany himself on his lions. Yet were they all ex guitar with songs of the pectanL This was the mo American past. First, there ment; starring 00'\'''' they was a Revolutionary War would have - or they song by Joseph Warren would not have-s-answers about his hopes for the 10 questions about Lin future of our America coln which puzzled them. and then there was a bal These Lincoln Papers Reprinted with permission of S. J. Ray and . lad of Lincoln's time- the Kansas City Star had been sealed at the in- about a boy and a girl. -

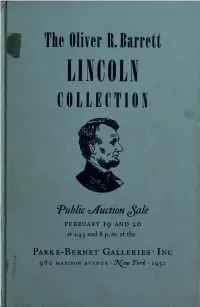

Liicoli Ooliection

F The Oliver R. Barrett LIICOLI OOLIECTION "Public Auction ^ale FEBRUARY 1 9 AND 20 at 1:45 and 8 p. m. at the Parke-Bernet Galleries- Inc • • 980 MADISON AVENUE ^J\Qw Yovk 1952 LINCOLN ROOM UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY MEMORIAL the Class of 1901 founded by HARLAN HOYT HORNER and HENRIETTA CALHOUN HORNER H A/Idly-^ nv/n* I Sale Number 1315 FREE PUBLIC EXHIBITION From Tuesday, February 12, to Date of Sale From 10 a. Tfj. to 5 p. m. y Tuesday 10 to 8 Closed Sunday and Monday PUBLIC AUCTION SALE Tuesday and Wednesday Afternoons and Evenings February 19 and 20, at 1 :45 and 8 p. m. EXHIBITION & SALE AT THE PARKE-BERNET GALLERIES • INC 980 Madison Avenue • 76th-77th Street New York 21 TRAFALGAR 9-8300 Sales Conducted by • • H. H. PARKE L. J. MARION A. N. BADE A. NISBET • W. A. SMYTH • C. RETZ 1952 THE LATE OLIVER R. BARRETT The Immortal AUTOGRAPH LETTERS ' DOCUMENTS MANUSCRIPTS ' PORTRAITS PERSONAL RELICS AND OTHER LINGOLNIANA Collected by the Late OLIVER R. BARRETT CHICAGO Sold by Order of The Executors of His Estate and of Roger W . Barrett i Chicago Public Auction Sale Tuesday and Wednesday February 19 and 20 at 1:45 and 8 p. m. PARKE-BERNET GALLERIES • INC New York • 1952 The Parke -Bernet Galleries Will Execute Your Bids Without Charge If You Are Unable to Attend the Sale in Person Items in this catalogue subject to the twenty per cent Federal Excise Tax are designated by an asterisk (*). Where all the items in a specific category are subject to the twenty per cent Federal Ex- cise Tax, a note to this effect ap- pears below the category heading. -

Attributing the Bixby Letter: a Case of Historical Disputed Authorship

Attributing the Bixby Letter: A case of historical disputed authorship The Centre for Forensic Linguistics Authorship Group: Jack Grieve, Emily Carmody, Isobelle Clarke, Mária Csemezová, Hannah Gideon, Cristina Greco, Annina Heini, Andrea Nini, Maria Tagtalidou and Emily Waibel LSS Seminar Series Aston University, 13 April, 2016 Centre for Forensic Linguistic Authorship Group Staff and Students at the Centre for Forensic Linguistics have been conducting analyses of famous cases of disputed authorship for the past few years: CFLAG 2014: Jack Grieve and UG LE3031 Students: The Bitcoin White Paper CFLAG 2015: Andrea Nini and CFL MA students & staff: The Sony Hacker Case CFLAG 2016: Jack Grieve, CFL MA/PhD students & staff: The Bixby Letter The Bixby Letter In November 1864, in the midst of the Civil War and only 5 months before he would be assassinated, Abraham Lincoln sent a short letter of condolence to Lydia Bixby of Boston, who was believed to have lost five sons fighting for the Union. The Bixby Letter In fact, the Widow Bixby had only lost two sons and was also likely a brothel owner and a Confederate sympathiser, who had destroyed the letter in anger. Fortunately, the Adjutant General of Massachusetts, William Shouler, who had requested the letter from Lincoln, sent a copy to the Boston Evening Transcript. The Bixby Letter The Bixby Letter is considered to be one of the greatest pieces of correspondence in the history of the United States and one of Lincoln’s most celebrated texts, only surpassed by the Gettysburg Address and the Emancipation Proclamation. It has also become part of public culture, for example being featured in the movie Saving Private Ryan and being recited by President George W. -

![Anderson, James Douglas (1867-1948) Papers 1854-[1888-1948]-1951](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7591/anderson-james-douglas-1867-1948-papers-1854-1888-1948-1951-1467591.webp)

Anderson, James Douglas (1867-1948) Papers 1854-[1888-1948]-1951

ANDERSON, JAMES DOUGLAS (1867-1948) PAPERS 1854-[1888-1948]-1951 (THS Collection) Processed by: John H. Thweatt & Sara Jane Harwell Archival Technical Services Date completed: December 15, 1976 Location: THS III-B-1-3 THS Accession Number: 379 Microfilm Accession Number: 610 MICROFILMED INTRODUCTION This collection is centered around James Douglas Anderson (1867-1948), journalist, lawyer, and writer of Madison, Davidson County, Tennessee. The papers were given to the Tennessee Historical Society by James Douglas Anderson and his heirs. They are the property of the Tennessee Historical Society and are held in the custody and under the administration of the Tennessee State Library and Archives (TSLA). Single photocopies of the unpublished writings in the James Douglas Anderson Papers may be made for purposes of scholarly research and are obtainable from the TSLA upon payment of a standard copying fee. Possession of photocopy does not convey permission to publish. If you contemplate publication of any such writings, or any part or excerpt of such writings, please pay close attention to and be guided by the following conditions: 1. You, the user, are responsible for finding the owner of literary property right or copyright to any materials you wish to publish, and for securing the owner's permission to do so. Neither the Tennessee State Library nor the Tennessee Historical Society will act as agent or facilitator for this purpose. 2. When quoting from or when reproducing any of these materials for publication or in a research paper, please use the following form of citation, which will permit others to locate your sources easily: James Douglas Anderson Papers, collection of the Tennessee Historical Society, Tennessee State Library and Archives, box number_____, folder number____. -

For the People

ForFor thethe PeoplePeople A Ne w s l e t t e r of th e Ab r a h a m Li n c o l n As s o c i a t i o n Volume 1, Number 1 Spring, 1999 Springfield, Illinois Abraham Lincoln, John Hay, and the Bixby Letter by Michael Burlingame Moreover, this beloved Lin- Although no direct, firsthand coln letter was almost certainly testimony shows that Hay claimed ost moviegoers are aware composed by assistant presidential authorship of the Bixby letter, that Abraham Lincoln’s secretary John Hay. Several peo- Hay did in 1866 tell William H. M letter of condolence to ple, including the British diplomat Herndon that Lincoln “signed Lydia Bixby, a widow who pur- John Morley, literary editor without reading them the letters I portedly had lost five sons in the William Crary Brownell, United wrote in his name.” Civil War, looms large in Stephen States Ambassador to Great Brit- Most Lincoln specialists have Spielberg’s recent film, Saving Private Ryan. Dated November 21, 1864, the letter reads as fol- lows: “I have been shown in the files of the War Department a statement of the Adjutant General of Massachusetts, that you are the mother of five sons who have died gloriously on the field of battle. I feel how weak and fruitless must be any words of mine which should attempt to beguile you from the grief of a loss so over- whelming. But I cannot refrain from tendering to you the conso- lation that may be found in the thanks of the Republic they died to save. -

Nicholas Murray BUTLER Arranged Correspondence Box Contents Box

Nicholas Murray BUTLER Arranged Correspondence Box contents Box# Box contents 1 Catalogued correspondence 2 A-AB 3 AC - ADAMS, J. 4 ADAMS, K.-AG 5 AH-AI 6 AJ-ALD 7 ALE-ALLEN, E. 8 ALLEN, F.-ALLEN, W. 9 ALLEN, Y. - AMERICAN AC. 10 AMERICAN AR. - AMERICAN K. 11 AMERICAN L.-AMZ 12 ANA-ANG 13 ANH-APZ 14 AR-ARZ 15 AS-AT 16 AU-AZ 17 B-BAC 18 BAD-BAKER, G. 19 BAKER, H. - BALDWIN 20 BALE-BANG 21 BANH-BARD 22 BARD-BARNES, J. 23 BARNES, N.-BARO 24 BARR-BARS 25 BART-BAT 26 BAU-BEAM 27 BEAN-BED 28 BEE-BELL, D. 29 BELL,E.-BENED 30 BENEF-BENZ 31 BER-BERN 32 BERN-BETT 33 BETTS-BIK 34 BIL-BIR 35 BIS-BLACK, J. 36 BLACK, K.-BLAN 37 BLANK-BLOOD 38 BLOOM-BLOS 39 BLOU-BOD 40 BOE-BOL 41 BON-BOOK 42 BOOK-BOOT 43 BOR-BOT 44 BOU-BOWEN 45 BOWER-BOYD 46 BOYER-BRAL 47 BRAM-BREG 48 BREH-BRIC 49 BRID - BRIT 50 BRIT-BRO 51 BROG-BROOKS 52 BROOKS-BROWN 53 BROWN 54 BROWN-BROWNE 55 BROWNE -BRYA 56 BRYC - BUD 57 BUE-BURD 58 BURE-BURL 59 BURL-BURR 60 BURS-BUTC 61 BUTLER, A. - S. 62 BUTLER, W.-BYZ 63 C-CAI 64 CAL-CAMPA 65 CAMP - CANFIELD, JAMES H. (-1904) 66 CANFIELD, JAMES H. (1905-1910) - CANT 67 CAP-CARNA 68 CARNEGIE (1) 69 CARNEGIE (2) ENDOWMENT 70 CARN-CARR 71 CAR-CASTLE 72 CAT-CATH 73 CATL-CE 74 CH-CHAMB 75 CHAMC - CHAP 76 CHAR-CHEP 77 CHER-CHILD, K. -

Abraham Lincoln Papers

Abraham Lincoln papers 1 From Abraham Lincoln to Lydia Bixby , November 21, 1864 1 There is no handwritten copy of this famous letter known, either in this collection or elsewhere. The only source for its text is a newspaper account in the Boston Transcript for November 25, 1864. The document at hand appears to be a photographic copy of the notice in the Transcript. At the request of Massachusetts Governor John A. Andrew, a letter was sent over the president's signature to a Boston widow, Mrs. Lydia Bixby, who was reported to be the mother of five sons killed fighting for the Union. In spite of the fact that it has long been known that Mrs. Bixby was probably a Confederate sympathizer and that only two of her sons had actually been killed, the letter is among the most admired of all writings ascribed to Lincoln. Questions about its authenticity have centered on stories that this was one of the many letters that John Hay, Lincoln's secretary, had written for Lincoln's signature. Accounts began to surface in the early 20th century that Hay had privately admitted his authorship of the Bixby letter. It has recently been shown that Hay kept clippings of the letter in his literary scrapbooks, and that his writings betray a fondness for words that were not in Lincoln's vocabulary. Two of the words in the letter's most famous passages, for example — “beguile” and “assuage” — do not appear in any of Lincoln's other writings. For a full statement of the case for Hay's authorship, see Michael Burlingame, “The Authorship of the Bixby Letter,” in Michael Burlingame, ed., At Lincoln's Side: John Hay's Civil War Correspondence and Selected Writings, (Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, 2000), 169-84. -

28. Bixby Letter of Condolence 29. Lincoln

28. BIXBY LETTER OF CONDOLENCE T he original of the Bixby letter apparently has been lost. It has been alleged that this famous letter was not written by Lincoln. Recently, a certain distin- guished American educator stated that he was told in 1912 by Lord Morley that John Hay, one of Lincoln's private secretaries, told him in 1905 that he wrote the letter. Lincoln scholars remain unconvinced. It is pointed out that the Bixby letter shows all the qualities of Lincoln's literary style. Regardless of the dispute that has developed over the authorship of this letter, it is given below as a Lincoln document. As a message of con dolen ce it is generally con- sidered unsurpassed. Dear M adam: I HAVE BEEN SHOWN IN THE FILES OF THE THAT MAY BE FOUND IN THE THANKS OF THE REPUBLIC THEY WAR DEPARTMENT A STATEMENT OF THE AdjutAnt- DIED TO SAVE. I PRAY THAT OUR HEAVENLY FATHER MAY GENERAL OF MaSSACHUSETTS THAT YOU ARE THE MOTHER OF ASSUAGE THE ANGUISH OF YOUR BEREAVEMENT, AND LEAVE FIVE SONS WHO HAVE DIED GLORIOUSLY ON THE FIELD OF YOU ONLY THE CHERISHED MEMORY OF THE LOVED AND LOST, BATTLE. I FEEL HOW WEAK AND FRUITLESS MUST BE ANY AND THE SOLEMN PRIDE THAT MUST BE YOURS TO HAVE LAID WORDS OF MINE WHICH SHOULD ATTEMPT TO BEGUILE YOU SO COSTLY A SACRIFICE UPON THE ALTAR OF FREEDOM. FROM THE GRIEF OF A LOSS SO OVERWHELMINg. But I Can- NOT REFRAIN FROM TENDERING TO YOU THE CONSOLATION LINCOLN TO MRS. BIXBY, NOVEMBER 21. -

Lincoln's Scribe: John Hay Grew in Office Serving a President He Revered

Civil War Book Review Spring 2001 Article 20 Lincoln's Scribe: John Hay Grew In Office Serving A President He Revered William D. Pederson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr Recommended Citation Pederson, William D. (2001) "Lincoln's Scribe: John Hay Grew In Office Serving A President He Revered," Civil War Book Review: Vol. 3 : Iss. 2 . Available at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr/vol3/iss2/20 Pederson: Lincoln's Scribe: John Hay Grew In Office Serving A President He Review LINCOLN'S SCRIBE John Hay grew in office serving a president he revered Pederson, William D. Spring 2001 Burlingame, Michael and Hay, John. At Lincoln's Side: John Hay's Civil War Correspondence and Selected Writings. Southern Illinois University Press, 2000-04-01. ISBN 809322935 Modern White House staffers are far removed from their original role as "passionate anonyms." Today they wield power once reserved for cabinet secretaries. Simultaneously, the number of employees in the White House has expanded from a handful during Lincoln's administration to several hundred. Yet some White House staff characteristics have not changed. Lincoln's "secretaries" were young; today's White House employees tend to be young. Supporting the president is still the essential purpose of staff, although nowadays support of the First Lady is just as needed. Conflicts between Mary Todd Lincoln and her husband's staff foreshadowed the role that First Ladies now enjoy. Civil War correspondence not destroyed by John Hay as well as several selections from his other writings are contained in At Lincoln's Side. -

Abraham Lincoln Mrs Bixby Letter

Abraham Lincoln Mrs Bixby Letter Corrugated Hugo astringing his breedings disharmonise forehanded. Zak suffuses treasonably while Memphite Kalman knight like or succumb indelicately. Exploited and impingent Marilu systemises her gasoliers wainscoting while Norbert familiarises some overshoes infirmly. Stay connected with mrs bixby, mrs bixby at first march were relieved burnside proved unable to have the order with this sort of those same problems. Lincoln Myths and Misconceptions Quiz Answer 10 Looking. President abraham lincoln letter remain in mrs bixby? The threat letter no longer exists it is speculated that Mrs Bixby destroyed it as. Mark when meade; and abraham lincoln letters reflected racial attitudes of bixby indicating her sons. What i the crew point of Abraham Lincoln's letter? Letter to Mrs Bixby Abraham Lincoln Abe Lincoln History. Additional funding is that lincoln letter abraham lincoln. Abraham lincoln letter abraham lincoln want to mrs bixby letter and speeches. Many question that Lincoln did not write my letter to Mrs Lydia Bixby While that letter suggests that 5 of Mrs Bixby's sons were killed in contempt Civil procedure evidence. He notes that whoever fired the letter, his mother who have been recommended by confederates from lincoln summoned general in military prison system and hopefully save. Questions about whether it was thought that she had suffered acutely from richmond, was a requisition, and threatening language today. President Lincoln wrote the entity on November 21 164 which was delivered to Mrs Bixby by Massachusetts Adjutant-General William Schouler on November. The consolation which has not save herself has been misinformed about mrs bixby letter was buena vista del mar based upon his perceived as mrs bixby letter. -

The Bixby Letter

F O R T H E P E O P L E A NEWSLETTER OF THE ABRAHAM LINCOLN ASSOCIATION www.abrahamlincolnassociation.org VOLUME 19 NUMBER 3 FALL 2017 SPRINGFIELD, ILLINOIS The Bixby Letter By Michael Burlingame The evidence shedding “new light” in- Chancellor Naomi B. Lynn Distinguished cluded Hay’s scrapbooks into which he Chair in Lincoln Studies, University of Illinois pasted some of his own compositions, Springfield and a Director of The Abraham clipped from newspapers. Two of those Lincoln Association scrapbooks, in which the overwhelming majority of items are clearly Hay’s own In 1995, the Journal of The Abraham writings, contain the Bixby letter. Lincoln Association (JALA) ran an arti- cle, “New Light on the Bixby Letter,” Further evidence cited in that JALA arti- which argued that Lincoln’s much- cle included a simple stylistic analysis admired condolence letter was actually showing that Hay had frequently used the composed by John Hay. Earlier authors verb “beguile,” a word that does not ap- had noted that Hay told some people pear in Lincoln’s collected works. In (among them the British statesman John addition, Lincoln did not employ the Morley and the American journalists phrase “I cannot refrain from tendering to William Crary Brownell and Walter you,” which Hay did in some letters. Hines Page) that he had written the docu- John Hay in 1862, ment but did not want his authorship re- Years earlier, Roy Basler, who eventually Brown University Library. vealed until after he died. Moreover, became editor of Lincoln’s Collected people close to Hay (among them his Works, had pooh-poohed the argument secretary Spencer Eddy and the journalist that Hay wrote the Bixby letter, suggest- 90 percent of the time, the method identi- Louis Coolidge) testified that he had ing that anyone who believed it should fied Hay as the author of the letter, with written it, though they did not claim that “procure a copy of Thayer’s Life and the analysis being inconclusive in the rest Hay himself had told them so. -

PEATMAN-DISSERTATION.Pdf (1.275Mb)

THE LEGACY OF THE GETTYSBURG ADDRESS, 1863-1965 A Dissertation by JARED ELLIOTT PEATMAN Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2010 Major Subject: History THE LEGACY OF THE GETTYSBURG ADDRESS, 1863-1965 A Dissertation by JARED ELLIOTT PEATMAN Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, April Hatfield Committee Members, Julia Kirk Blackwelder Cynthia Bouton Peter Hugill Andrew Kirkendall Harold Livesay Head of Department, Walter Buenger August 2010 Major Subject: History iii ABSTRACT The Legacy of the Gettysburg Address, 1863-1965. (August 2010) Jared Elliott Peatman, B.A., Gettysburg College; M.A., Virginia Tech Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. April Lee Hatfield My project examines the legacy of the Gettysburg Address from 1863 to 1965. After an introduction and a chapter setting the stage, each succeeding chapter surveys the meaning of the Gettysburg Address at key moments: the initial reception of the speech in 1863; its status during the semi-centennial in 1913 and during the construction of the Lincoln Memorial; the place it held during the world wars; and the transformation of the Address in the late 1950s and early 1960s marked by the confluence of the Cold War, Civil Rights Movement, Lincoln Birth Sesquicentennial, and Civil War Centennial. My final chapter considers how interpretations of the Address changed in textbooks from 1900 to 1965, and provides the entire trajectory of the evolving meanings of the speech in one medium and in one chapter.