POLICY PAPER INEQUALITY, INJUSTICE and INDIA's FORGOTTEN PEOPLE ABSTRACT the Boston Consulting Group's 15Th Annual Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STATISTICAL REPORT GENERAL ELECTIONS, 2004 the 14Th LOK SABHA

STATISTICAL REPORT ON GENERAL ELECTIONS, 2004 TO THE 14th LOK SABHA VOLUME III (DETAILS FOR ASSEMBLY SEGMENTS OF PARLIAMENTARY CONSTITUENCIES) ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA NEW DELHI Election Commission of India – General Elections, 2004 (14th LOK SABHA) STATISCAL REPORT – VOLUME III (National and State Abstracts & Detailed Results) CONTENTS SUBJECT Page No. Part – I 1. List of Participating Political Parties 1 - 6 2. Details for Assembly Segments of Parliamentary Constituencies 7 - 1332 Election Commission of India, General Elections, 2004 (14th LOK SABHA) LIST OF PARTICIPATING POLITICAL PARTIES PARTYTYPE ABBREVIATION PARTY NATIONAL PARTIES 1 . BJP Bharatiya Janata Party 2 . BSP Bahujan Samaj Party 3 . CPI Communist Party of India 4 . CPM Communist Party of India (Marxist) 5 . INC Indian National Congress 6 . NCP Nationalist Congress Party STATE PARTIES 7 . AC Arunachal Congress 8 . ADMK All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam 9 . AGP Asom Gana Parishad 10 . AIFB All India Forward Bloc 11 . AITC All India Trinamool Congress 12 . BJD Biju Janata Dal 13 . CPI(ML)(L) Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) (Liberation) 14 . DMK Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam 15 . FPM Federal Party of Manipur 16 . INLD Indian National Lok Dal 17 . JD(S) Janata Dal (Secular) 18 . JD(U) Janata Dal (United) 19 . JKN Jammu & Kashmir National Conference 20 . JKNPP Jammu & Kashmir National Panthers Party 21 . JKPDP Jammu & Kashmir Peoples Democratic Party 22 . JMM Jharkhand Mukti Morcha 23 . KEC Kerala Congress 24 . KEC(M) Kerala Congress (M) 25 . MAG Maharashtrawadi Gomantak 26 . MDMK Marumalarchi Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam 27 . MNF Mizo National Front 28 . MPP Manipur People's Party 29 . MUL Muslim League Kerala State Committee 30 . -

![296] CHENNAI, FRIDAY, OCTOBER 1, 2010 Purattasi 15, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2041](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7728/296-chennai-friday-october-1-2010-purattasi-15-thiruvalluvar-aandu-2041-407728.webp)

296] CHENNAI, FRIDAY, OCTOBER 1, 2010 Purattasi 15, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2041

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2009-11. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2010 [Price: Rs. 20.00 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 296] CHENNAI, FRIDAY, OCTOBER 1, 2010 Purattasi 15, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2041 Part V—Section 4 Notifications by the Election Commission of India. NOTIFICATIONS BY THE ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA ELECTION SYMBOLS (RESERVATION AND ALLOTMENT) ORDER, 1968 No. SRO G-33/2010. The following Notification of the Election Commission of India, Nirvachan Sadan, Ashoka Road, New Delhi-110 001, dated 17th September, 2010 [26 Bhadrapada, 1932 (Saka)] is republished:— Whereas, the Election Commission of India has decided to update its Notification No. 56/2009/P.S.II, dated 14th September, 2009, specifying the names of recognised National and State Parties, registered-unrecognised parties and the list of free symbols, issued in pursuance of paragraph 17 of the Election Symbols (Reservation and Allotment) Order, 1968, Now, therefore, in pursuance of paragraph 17 of the Election Symbols (Reservation and Allotment) Order, 1968, and in supersession of its aforesaid Notification No. 56/2009/P.S.II, dated 14th September, 2009, as amended from time to time, published in the Gazette of India, Extraordinary, Part II—Section-3, sub-section (iii), the Election Commission of India hereby specifies :— (a) In Table I, the National Parties and the Symbols respectively reserved for them and postal address of their Headquarters ; (b) In Table II, the State Parties, the State or States in which they are State Parties and the Symbols respectively reserved for them in such State or States and postal address of their Headquarters; (c) In Table III, the registered-unrecognised political parties and postal address of their Headquarters; and (d) In Table IV, the free symbols. -

Performance of Political Parties and Independents

PERFORMANCE OF POLITICAL PARTIES AND INDEPENDENTS NATIONAL PARTY Total Valid No. of ACs No. of Votes % of votes Name of Political Party Votes of the Contested Winner Polled Polled State Bahujan Samaj Party 14 0 9135818 321571 3.52 Bharatiya Janata Party 12 8 9135818 2515265 27.53 Communist Party of India 309135818 106051 1.16 Communist Party of India (Marxist) 209135818 49407 0.54 Indian National Congress 919135818 1372639 15.02 Rashtriya Janata Dal 609135818 486870 5.33 STATE PARTY Total Valid No. of ACs No. of Votes % of votes Name of Political Party Votes of the Contested Winner Polled Polled State Janata Dal (United) 209135818 110912 1.21 Jharkhand Mukti Morcha 829135818 1068935 11.70 REGISTERED UNRECOGNIZED PARTIES Total Valid No. of ACs No. of Votes % of votes Name of Political Party Votes of the Contested Winner Polled Polled State AJSU Party 609135818 200523 2.19 Akhil Bharat Hindu Mahasabha 109135818 2363 0.03 Akhil Bharatiya Manav Seva Dal 209135818 11298 0.12 All India Forward Bloc 109135818 5291 0.06 All India Trinamool Congress 209135818 12563 0.14 Amra Bangalee 209135818 12505 0.14 Bahujan Shakty 309135818 12984 0.14 Bharatiya Jagaran Party 109135818 7024 0.08 Bharatiya Samta Samaj Party 109135818 6334 0.07 Communist Party of India (Marxist- Leninist) (Liberation) 6 0 9135818 254455 2.79 Indian Justice Party 1 0 9135818 1934 0.02 Janata Dal (Secular) 1 0 9135818 1999 0.02 Jharkhand Disom Party 2 0 9135818 13206 0.14 Jharkhand Jan Morcha 1 0 9135818 58025 0.64 Jharkhand Janadikhar Manch 1 0 9135818 32219 0.35 Jharkhand Party 7 0 9135818 125900 1.38 Jharkhand Party (Naren) 5 0 9135818 43294 0.47 Jharkhand People'S Party 1 0 9135818 2498 0.03 Jharkhand Vikas Dal 5 0 9135818 45245 0.50 Jharkhand Vikas Morcha (Prajatantrik) 14 1 9135818 957084 10.48 Lok Jan Shakti Party 3 0 9135818 33270 0.36 Lok Jan Vikas Morcha 1 0 9135818 3658 0.04 Manav Mukti Morcha 1 0 9135818 8839 0.10 Marxist Co-Ordination 2 0 9135818 91489 1.00 Office of the Chief Electoral Officer, Jharkhand 1 General Election to the Lok Sabha 2009 Total Valid No. -

Statistical Reports 2005

STATISTICAL REPORT ON GENERAL ELECTION, 2005 TO THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF JHARKHAND ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA NEW DELHI ECI-GE2005-VS Election Commission of India, 2005 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by mimeograph or any other means, without prior and express permission in writing from Election Commision of India. First published 2005 Published by Election Commision of India, Nirvachan Sadan, Ashoka Road, New Delhi - 110 001. Computer Data Processing and Laser Printing of Reports by Statistics & Information System Division, Election Commision of India. Election Commission of India – State Elections, 2005 to the Legislative Assembly of JHARKHAND STATISTICAL REPORT CONTENTS SUBJECT Page No. 1. List of Participating Political Parties and Abbreviations 1 -2 2. Other Abbreviations in the Report 3 3. Highlights 4 4. List of Successful Candidates 5 - 7 5. Performance of Political Parties 8 -10 6. Candidates Data Summary – Summary on Nominations, 11 Rejections, Withdrawals and Forfeitures 7. Electors Data Summary – Summary on Electors, voters 12 Votes Polled and Polling Stations 8. Woman Candidates 13 - 16 9. Constituency Data Summary 17 - 97 10. Detailed Result 98 - 226 Election Commission of India-State Elections, 2005 to the Legislative Assembly of Jharkhand LIST OF PARTICIPATING POLITICAL PARTIES PARTYTYPE ABBREVIATION PARTY NAM PARTY HINDI NAME NATIONAL PARTIES 1 . BJP Bharatiya Janata Party भारतीय जनता पाट 2 . BSP Bahujan Samaj Party बहजनु समाज पाट 3 . CPI Communist Party of India कयुिनःट पाट ऑफ इंडया 4 . CPM Communist Party of India भारत क कयुिनःट पाट (मासवाद) (Marxist) 5 . -

Number and Types of Constituencies

Election Commission of India, General Elections, 2009 (15th LOK SABHA) 3 - NUMBER AND TYPES OF CONSTITUENCIES STATE/UT Type of Constituencies Gen SC ST Total No Of Constituencies Where Election Completed Andhra Pradesh 32 7 3 42 42 Arunachal Pradesh 2 0 0 2 2 Assam 11 1 2 14 14 Bihar 34 6 0 40 40 Goa 2 0 0 2 2 Gujarat 20 2 4 26 26 Haryana 8 2 0 10 10 Himachal Pradesh 3 1 0 4 4 Jammu & Kashmir 6 0 0 6 6 Karnataka 21 5 2 28 28 Kerala 18 2 0 20 20 Madhya Pradesh 19 4 6 29 29 Maharashtra 39 5 4 48 48 Manipur 1 0 1 2 2 Meghalaya 0 0 2 2 2 Mizoram 0 0 1 1 1 Nagaland 0 0 1 1 1 Orissa 13 3 5 21 21 Punjab 9 4 0 13 13 Rajasthan 18 4 3 25 25 Sikkim 1 0 0 1 1 Tamil Nadu 32 7 0 39 39 Tripura 1 0 1 2 2 Uttar Pradesh 63 17 0 80 80 West Bengal 30 10 2 42 42 Chattisgarh 6 1 4 11 11 Jharkhand 8 1 5 14 14 Uttarakhand 4 1 0 5 5 Andaman & Nicobar Islands 1 0 0 1 1 Chandigarh 1 0 0 1 1 Dadra & Nagar Haveli 1 0 0 1 1 Daman & Diu 1 0 0 1 1 NCT OF Delhi 6 1 0 7 7 Lakshadweep 0 0 1 1 1 Puducherry 1 0 0 1 1 Total 412 84 47 543 543 1 Election Commission of India, General Elections, 2009 (15th LOK SABHA) 4 - POLLING STATION INFORMATION Polling Stations General Electors Service Electors Grand Total State/UT PC No. -

India 2020 International Religious Freedom Report

INDIA 2020 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The constitution provides for freedom of conscience and the right of all individuals to freely profess, practice, and propagate religion; mandates a secular state; requires the state to treat all religions impartially; and prohibits discrimination based on religion. It also states that citizens must practice their faith in a way that does not adversely affect public order, morality, or health. Ten of the 28 states have laws restricting religious conversions. In February, continued protests related to the 2019 Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), which excludes Muslims from expedited naturalization provisions granted to migrants of other faiths, became violent in New Delhi after counterprotestors attacked demonstrators. According to reports, religiously motivated attacks resulted in the deaths of 53 persons, most of whom were Muslim, and two security officials. According to international nongovernmental organization (NGO) Human Rights Watch, “Witnesses accounts and video evidence showed police complicity in the violence.” Muslim academics, human rights activists, former police officers, and journalists alleged anti-Muslim bias in the investigation of the riots by New Delhi police. The investigations were still ongoing at year’s end, with the New Delhi police stating it arrested almost equal numbers of Hindus and Muslims. The government and media initially attributed some of the spread of COVID-19 in the country to a conference held in New Delhi in March by the Islamic Tablighi Jamaat organization after media reported that six of the conference’s attendees tested positive for the virus. The Ministry of Home Affairs initially claimed a majority of the country’s early COVID-19 cases were linked to that event. -

List of Participating Political Parties

Election Commission of India- State Election, 2010 to the Legislative Assembly Of Bihar LIST OF PARTICIPATING POLITICAL PARTIES PARTY TYPE ABBREVIATION PARTY NATIONAL PARTIES 1 . BJP Bharatiya Janata Party 2 . BSP Bahujan Samaj Party 3 . CPI Communist Party of India 4 . CPM Communist Party of India (Marxist) 5 . INC Indian National Congress 6 . NCP Nationalist Congress Party STATE PARTIES 7 . JD(U) Janata Dal (United) 8 . LJP Lok Jan Shakti Party 9 . RJD Rashtriya Janata Dal STATE PARTIES - OTHER STATES 10 . AIFB All India Forward Bloc 11 . JD(S) Janata Dal (Secular) 12 . JKNPP Jammu & Kashmir National Panthers Party 13 . JMM Jharkhand Mukti Morcha 14 . JVM Jharkhand Vikas Morcha (Prajatantrik) 15 . MUL Muslim League Kerala State Committee 16 . RSP Revolutionary Socialist Party 17 . SHS Shivsena 18 . SP Samajwadi Party REGISTERED(Unrecognised) PARTIES 19 . ABAPSMP AKHIL BHARTIYA ATYANT PICHARA SANGHARSH MORCHA PARTY 20 . ABAS Akhil Bharatiya Ashok Sena 21 . ABDBM Akhil Bharatiya Desh Bhakt Morcha 22 . ABHKP Akhil Bharatiya Hind Kranti Party 23 . ABHM Akhil Bharat Hindu Mahasabha 24 . ABJS Akhil Bharatiya Jan Sangh 25 . ABSP Akhand Bharat Samaj Party 26 . AD Apna Dal 27 . AIBJRBSNC All India Babu Jagjivan Ram Saheb National Congress 28 . AIFB(S) All India Forward Bloc (Subhasist) 29 . AJSP Alpjan Samaj Party 30 . AKBMP Akhil Bharitya Mithila Party 31 . ANC Ambedkar National Congress 32 . AP Awami Party ASSEMBLY ELECTIONS - INDIA (Bihar ), 2010 LIST OF PARTICIPATING POLITICAL PARTIES PARTY TYPE ABBREVIATION PARTY REGISTERED(Unrecognised) PARTIES 33 . BED Bharatiya Ekta Dal 34 . BEP(R) Bahujan Ekta Party ( R ) 35 . BHAJP Bharatiya Jagaran Party 36 . BIP Bharatiya Inqalab Party 37 . -

E:\Election Backgrounder\P1-10

SEVENTEENTH GENERAL ELECTIONS TO LOK SABHA ELECTION BACKGROUNDER, ODISHA-2019 Shri Sanjay Kumar Singh, I.A.S Shri Laxmidhar Mohanty, O.A.S(SAG) Commissioner-cum-Secretary Director Shri Subhendra Kumar Nayak, O.A.S(S) Shri Niranjan Sethi Joint Secretary Addl. Director-cum-Joint Secretary Shri Barada Prasanna Das Deputy Director-cum-Deputy Secretary Compilation & Editing Shri Surya Narayan Mishra Shri Debasis Pattnaik Shri Sachidananda Barik Dr. Prasant Kumar Praharaj Co-ordination Shri Biswajit Dash Shri Santosh Kumar Das Shri Prafulla Kumar Mallick Shri Pathani Rout Cover Design Shri Manas Ranjan Nayak DTP & Layout Shri Hemanta Kumar Sahoo Shri Kabyakanta Mohanty Shri Abhimanyu Gouda Published by Information & Public Relations Department Government of Odisha CONTENTS 1. FOREWORD 2. SEVENTEENTH LOK SABHA ELECTION, ODISHA, 2019 3. LIST OF PARLIAMENTARY CONSTITUENCIES GOING TO POLL (2019) ON PHASE-WISE 4. FACTS AT A GLANCE (SUCCESSIVE GENERAL ELECTIONS) 5. ALL INDIA PARTY POSITION IN LOK SABHA FROM 1951-52 TO 2014 6. VOTES POLLED–SEATS WON ANALYSIS (1996, 1998, 1999, 2004, 2009, 2014) 7. STATE/UT-WISE SEATS IN THE LOK SABHA 8. LOK SABHA ELECTION, ODISHA (1951-52 TO 2014) 9. PARTY-WISE PERFORMANCE IN LOK SABHA ELECTIONS OF ODISHA FROM 1951 TO 2014 10. PARLIAMENTARY CONSTITUENCIES AFTER DELIMITATION 11. ELECTIONS TO THE SIXTEENTH LOK SABHA, 2014 : ODISHA AT A GLANCE 12. ELECTIONS TO THE SEVENTEENTH LOK SABHA, 2019 : ODISHA AT A GLANCE 13. TOTAL NUMBER OF POLLING STATIONS (CONSTITUENCY-WISE) SEVENTEENTH LOK SABHA, 2019 14. NUMBER OF ELECTORS IN THE ELECTORAL ROLL 2019 (P.C. / A.C.-WISE) WITH POLLING STATIONS 15. -

Election Commission of India

TO BE PUBLISHED IN THE GAZETTE OF INDIA EXTRAORDINARY, PART II, SECTION 3, SUB-SECTION (iii) IMMEDIATELY ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA Nirvachan Sadan, Ashoka Road, New Delhi – 110001 No.56/2008/PPS Dated : 17th October, 2008. 25, Asvina, 1930 (Saka). NOTIFICATION WHEREAS, the Election Commission of India has decided to update its Notification No. 56/2007/J.S.III, dated 6th January, 2007, specifying the names of recognised National and State Parties, registered-unrecognised parties and the list of free symbols, issued in pursuance of paragraph 17 of the Election Symbols (Reservation and Allotment) Order, 1968, as amended from time to time; NOW, THEREFORE, in pursuance of paragraph 17 of the Election Symbols (Reservation and Allotment) Order, 1968, and in supersession of its aforesaid principal notification No. 56/2007/J.S.III, dated 6th January, 2007, published in the Gazette of India, Extra- Ordinary, Part-II, Section-3, Sub-Section (iii), the Election Commission of India hereby specifies: - (a) In Table I, the National Parties and the Symbols respectively reserved for them and postal address of their Headquarters; (b) In Table II, the State Parties, the State or States in which they are State Parties and the Symbols respectively reserved for them in such State or States and postal address of their Headquarters; (c) In Table III, the registered-unrecognized political parties and postal address of their Headquarters; and (d) In Table IV, the free symbols. TABLE – I NATIONAL PARTIES Sl. National Parties Symbol reserved Address No. 1. 2. 3. 4. 1.Bahujan Samaj Party Elephant 16, Gurudwara Rakabganj [ In all States/U.T.s except Road, New Delhi – 110001. -

The Moral Governance of Adivasis And

INEBRIETY AND INDIGENEITY: THE MORAL GOVERNANCE OF ADIVASIS AND ALCOHOL IN JHARKHAND, INDIA By Roger Begrich A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland October 2013 © 2013 Roger Begrich All Rights Reserved Abstract This dissertation is an investigation of alcohol and indigeneity in India. Based on 20 months of ethnographic fieldwork in the state of Jharkhand, I aim to describe the complex and contradictory roles that alcohol plays in the lives of people variously referred to adivasis, tribals, or Scheduled Tribes. By taking a closer look at the presence of alcohol in various registers of adivasi lives (economy, religion, social relations) as well as by studying the ways alcohol is implicated in the constitution of adivasis as a distinct category of governmental subjects, I hope to provide a nuanced and multilayered account of the relationships between adivasis and alcohol. I will thereby conceptualize these relationships in terms of obligations, which will allow me to approach them without the constraints of determination or causality inherent in concepts like addiction and/or alcoholism, and to circumvent the notion of compulsion implied in ideas about adivasis as either culturally or genetically predisposed to drinking. In the chapters that follow, I will first discuss how the criterion of alcohol consumption is implicated, discursively, in the constitution of adivasis as a separate population, and a distinct subject category through -

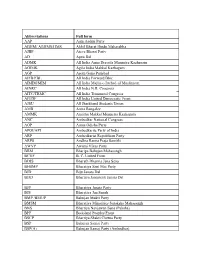

Abbreviations Full Form AAP Aam Aadmi Party ABHM

Abbreviations Full form AAP Aam Aadmi Party ABHM/ ABHMS/HMS Akhil Bharat Hindu Mahasabha AJBP Ajeya Bharat Party AD Apna Dal ADMK All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam AGIMK Agila India Makkal Kazhagam AGP Asom Gana Parishad AIFB/FBL All India Forward Bloc AIMIM/MIM All India Majlis-e-Ittehad-ul Muslimeen AINRC All India N.R. Congress AITC/TRMC All India Trinamool Congress AIUDF All India United Democratic Front AJSU All Jharkhand Students Union AMB Amra Bangalee AMMK Anaithu Makkal Munnetra Kazhagam ANC Ambedkar National Congress AOP Aama Odisha Party APOI/API Ambedkarite Party of India ARP Ambedkarist Republican Party ARPS Andhra Rastra Praja Samithi AWVP Awami Vikas Party BBM Bharipa Bahujan Mahasangh BCUF B. C. United Front BDJS Bharath Dharma Jana Sena BHSMP Bharatiya Sant Mat Party BJD Biju Janata Dal BJJD Bhartiya Jantantrik Janata Dal BJP Bharatiya Janata Party BJS Bharatiya Jan Sangh BMP /BMUP Bahujan Mukti Party BMSM Bharatiya Minorities Suraksha Mahasangh BNS Bhartiya Navjawan Sena (Paksha) BPF Bodoland Peoples Front BSCP Bhartiya Shakti Chetna Party BSP Bahujan Samaj Party BSP(A) Bahujan Samaj Party (Ambedkar) BVA Bahujan Vikas Aaghadi BVM Bharat Vikas Morcha CMP/CMP (J) Communist Marxist party Cong(S) Congress (Secular) CPI Communist Party of India CPI(ML) Red Star Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) Red Star CPIML (L) Communist Party of India (Marxist–Leninist) Liberation CPM Communist Party of India (Marxist) DABP Dalita Bahujana Party DJP Delhi Janta Party DMDK Desiya Murpokku Dravida Kazhagam DMK Dravida Munnetra -

Political Party & Election Symbol

© Election Commission of India, 2007 Published by Media Coordination & Publication Division, Election Commission of India, Nirvachan Sadan, Ashoka Road, New Delhi-110001 and produced by Ashok Creatives, India Tourism Development Corporation and printed at M/s. I.G. Printers, New Delhi. Tel : 91-11-23717391 Fax : 91-11-23713412 Website : www.eci.gov.in THE ELECTION SYMBOLS (RESERVATION AND ALLOTMENT) ORDER, 1968 AN ORDER to provide for specification, reservation, choice and allotment of symbols at elections in Parliamentary and Assembly Constituencies, for the recognition of political parties in relation thereto and for matters connected therewith. S.O. 2959, dated the 31st August, 1968 – WHEREAS, the superintendence, direction and control of all elections to Parliament and to the Legislature of every State are vested by the Constitution of India in the Election Commission of India; AND WHEREAS, it is necessary and expedient to provide, in the interest of purity of elections to the House of the People and the Legislative Assembly of every State and in the interest of the conduct of such elections in a fair and efficient manner, for the specification, reservation, choice and allotment of symbols, for the recognition of political parties in relation thereto and for matters connected therewith; NOW THEREFORE, in exercise of the powers conferred by Article 324 of the Constitution 1 [read with section 29A of the Representation of the People Act, 1951 (43 of 1951)] and rules 5 and 10 of the Conduct of Elections Rules, 1961 and all other powers enabling it in this behalf, the Election Commission of India hereby makes the following Order :- 1.