Scottish Rugby Internationalists Who Fell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Three Day Golfing & Sporting Memorabilia Sale

Three Day Golfing & Sporting Memorabilia Sale - Day 2 Wednesday 05 December 2012 10:30 Mullock's Specialist Auctioneers The Clive Pavilion Ludlow Racecourse Ludlow SY8 2BT Mullock's Specialist Auctioneers (Three Day Golfing & Sporting Memorabilia Sale - Day 2) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 1001 Rugby League tickets, postcards and handbooks Rugby 1922 S C R L Rugby League Medal C Grade Premiers awarded League Challenge Cup Final tickets 6th May 1950 and 28th to L McAuley of Berry FC. April 1956 (2 tickets), 3 postcards – WS Thornton (Hunslet), Estimate: £50.00 - £65.00 Hector Crowther and Frank Dawson and Hunslet RLFC, Hunslet Schools’ Rugby League Handbook 1963-64, Hunslet Schools’ Rugby Union 1938-39 and Leicester City v Sheffield United (FA Cup semi-final) at Elland Road 18th March 1961 (9) Lot: 1002 Estimate: £20.00 - £30.00 Keighley v Widnes Rugby League Challenge Cup Final programme 1937 played at Wembley on 8th May. Widnes won 18-5. Folded, creased and marked, staple rusted therefore centre pages loose. Lot: 1009 Estimate: £100.00 - £150.00 A collection of Rugby League programmes 1947-1973 Great Britain v New Zealand 20th December 1947, Great Britain v Australia 21st November 1959, Great Britain v Australia 8th October 1960 (World Cup Series), Hull v St Helens 15th April Lot: 1003 1961 (Challenge Cup semi-final), Huddersfield v Wakefield Rugby League Championship Final programmes 1959-1988 Trinity 19th May 1962 (Championship final), Bradford Northern including 1959, 1960, 1968, 1969, 1973, 1975, 1978 and -

Vollume 20, No 4 2004

But I asked him to pick me up a Big Mac PEER PRESSURE! Just say yes School Nurse seeks funds for staff special needs JJ makes his mark on the school No blushes - just blooming magic! Not calves - cows! And I was onto the green in five! CONTENTS CAPTAINS OF SCHOOL 2 SWIM TEAM 66 STAFF NOTES 3 BADMINTON / SAILING 67 VALETE 4 GOLF REPORT 2004 68 OBITUARY - REVD TREVOR STEVENS 7 F IT B A ’ 69 S P E E C H DAY 8 SKI SEASON 2003-2004 70 SCHOOL HOUSES 10 GIRLS’TENNIS/CYCLING 71 RILEY HOUSE 10 BOYS' TENNIS 72 FREELAND HOUSE 12 A HAWK IN WINTER 73 NICOL HOUSE 14 EQUESTRIANISM 74 RUTHVEN HOUSE 16 SIMPSON HOUSE 18 SHOOTING 75 THORNBANK HOUSE 20 SUB AQUA 76 WOODLANDS HOUSE 22 PAST. PRESENT AND FUTURE 78 HEADMASTER S SUMMER MUSIC 2 4 A R M Y 86 MUSIC 26 TA B O R 88 THE CHAPEL CHOIR TOUR OF VISITING LECTURERS 89 THE NORTH OF ENGLAND 28 P R A G U E 90 NATIONAL YOUTH CHOIR OF SCOTLAND 29 MONTPELLIER 92 P IP IN G 30 STRATHALLIAN DAY TWELFTH NIGHT OR WHAT YOU WILL 32 /LAUNCH OF NEW WEBSITE 93 LES MISERABLES 3 4 SIXTH FORM COMMON ROOM REPORT 03-04 94 SENIOR HOUSE DRAMA 3 7 SIXTH FORM 95 SPEECH & DRAMA 3 8 TRIATHLON / IV AND V FORM REELS 96 ESSAY COMPETITION 39 WOODFAIR 97 S A LV E T E 04 40 SIXTH FORM BALL 2004 98 ART & DESIGN 4 2 SIXTH FORM 99 DESIGN & TECHNOLOGY 4 8 STRATHSTOCK 2004 100 C R IC K E T 52 A R T S H O W / FASHION SHOW EXTRAVAGANZA 102 RUGBY 56 B U R N S ’ S U P P E R MARATHON WOMAN 59 /STRATHMORE CHALLENGE 104 CROSS COUNTRY AND ATHLETICS 2004 60 FORENSIC SCIENCE TASTER DAY BOYS' HOCKEY 62 /MILLPORT 105 G IR L S ’ H O C K E Y 63 OBITUARIES 106 GIRLS’ HOCKEY TOUR 2004 64 VALETE 04 110 Volume XX No. -

Lieutenant Cecil Halliday Abercrombie

Lieutenant Cecil Halliday Abercrombie, Royal Navy, born at Mozufferpore, India, on 12 September 1886, was the son of Walter D Abercrombie, Indian Police, and Kate E Abercrombie. In cricket, he was a right hand bat and right hand medium pace bowler. In 1912 he hit 37 and 100 for the Royal Navy v Army at Lord’s. He played for Hampshire Cricket Club in 1913, scoring 126 and 39 in his debut against Oxford University, 144 v Worcestershire and 165 v Essex when Hampshire followed on 317 behind; in a stand with George Brown (140) he put on 325 for the seventh wicket. In first class matches that year he scored 936 runs with an average of 35.92. Between 1910 and 1913, he played six times for Scotland (won 2, lost 4). He was lost with HMS Defence on 31 May 1916, age 29, and is commemorated on the Plymouth Naval Memorial. His widow was Cecily Joan Abercrombie (nee Baker) of 22 Cottesmore Gardens, Kensington, London. (The following is from "The Rugby Roll of Honour" by E H D Sewell, published in 1919) Lieutenant Cecil Halliday Abercrombie, Royal Navy, was born at Mozufferpore, India, on 12 September 1886, and fell in action on HMS Defence at the Battle of Jutland, on May 31, 1916, aged 29. He was educated at Allan House, Guildford, at Berkhamsted School, and on HMS Britannia. He was in the 1st XI and XV, both at school and of the Britannia, and on the training ship won for his Term the High Jump, Long Jump, Racquets, Fives, and Swimming, thus early his versatility proving the shadow of the coming event. -

November 2014

FREE November 2014 OFFICIAL PROGRAMME www.worldrugby.bm GOLF TouRNAMENt REFEREEs LIAIsON Michael Jenkins Derek Bevan mbe • John Weale GROuNds RuCK & ROLL FRONt stREEt Cameron Madeiros • Chris Finsness Ronan Kane • Jenny Kane Tristan Loescher Michael Kane Trevor Madeiros (National Sports Centre) tEAM LIAIsONs Committees GRAPHICs Chief - Pat McHugh Carole Havercroft Argentina - Corbus Vermaak PREsIdENt LEGAL & FINANCIAL Canada - Jack Rhind Classic Lions - Simon Carruthers John Kane, mbe Kim White • Steve Woodward • Ken O’Neill France - Marc Morabito VICE PREsIdENt MEdICAL FACILItIEs Italy - Guido Brambilla Kim White Dr. Annabel Carter • Dr. Angela Marini New Zealand - Brett Henshilwood ACCOMMOdAtION Shelley Fortnum (Massage Therapists) South Africa - Gareth Tavares Hilda Matcham (Classic Lions) Maureen Ryan (Physiotherapists) United States - Craig Smith Sue Gorbutt (Canada) MEMbERs tENt TouRNAMENt REFEREE AdMINIstRAtION Alex O'Neill • Rick Evans Derek Bevan mbe Julie Butler Alan Gorbutt • Vicki Johnston HONORARy MEMbERs CLAssIC CLub Harry Patchett • Phil Taylor C V “Jim” Woolridge CBE Martine Purssell • Peter Kyle MERCHANdIsE (Former Minister of Tourism) CLAssIC GAs & WEbsItE Valerie Cheape • Debbie DeSilva Mike Roberts (Wales & the Lions) Neil Redburn Allan Martin (Wales & the Lions) OVERsEAs COMMENtARy & INtERVIEWs Willie John McBride (Ireland & the Lions) Argentina - Rodolfo Ventura JPR Williams (Wales & the Lions) Hugh Cahill (Irish Television) British Isles - Alan Martin Michael Jenkins • Harry Patchett Rodolfo Ventura (Argentina) -

Scotland Players

%./{/yo«// • RUGBY FOOTBALL UNION Look for the Gin in the six-sided bottle, and take home a bottle to-day ! MAXIMUM PRICES IN U.K. Bottle 33z9 Half Bot:!a VH • Qtr. Bottle 9'2 • Miniature 3/7 M^/ief/ieri/cu want A SINGLE JOIST RUGBY FOOTBALL UNION A COMPLETE BUILDING VERSUS STEELWORK SERVICE TWICKENHAM 21st March 1953 RUGBY FOOTBALL UNION 1952-53 PATRON: H.M. THE QUEEN President: P. M. HOLMAN (Cornwall) Vice-Presidents: IMPiMNKEN-• ltd J. BRUNTON, D.S.O.J M.C. (Northumberland) W. C. RAMSAY (Middlesex) CONSTRUCTIONAL ENGINEERS Hon. Treasurer-. W. C. RAMSAY Secretary: F. D. PRENTICE -- IRON & STEEL STOCKHOLDERS J • - . - SCOTTISH RUGBY UNION .TELEPHONE I EEEE 5 TELEGRAMS 2-7 3 O I (20 LINES) •• • •» •• "SECTIONS LEEDS President: F. J. C MOFFAT (Watsonians) Vice-President: M. A. ALLAN (Glasgow Academicals) Secretary and Treasurer: F. A. WRIGHT 3 This Year's '"N Interna tidhals Down shines the hilarating picture sun and down goes are (left to right) Adkins in Eng Holmes, Lewis, land's match with Kendall - Carpenter France three weeks and Wilson. The ago. Other English French tackier men in this ex , is Marcel Celaya. SCOTLAND v WALES The great Welsh forward Roy John handing off the Scottish captain, A. F. Dorward, in the match at Murrayfield. Wales won by one penalty goal and three tries (12 points) to nil. WALES v. ENGLAND Thv new Welsh wing in action . Gareth Griffiths, threatened by his opposite number, J. E. Woodward, about to cross-kick. Malcolm Thomas of Newport can be seen between the two. IRELAND v. -

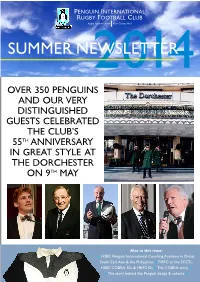

Summer Newsletter

PENGUIN INTERNATIONAL RUGBY FOOTBALL CLUB Rugby Football Union Kent County RFU SUMMER NEWSLETTER2014 OVER 350 PENGUINS AND OUR VERY DISTINGUISHED GUESTS CELEBRATED THE CLUB’S 55TH ANNIVERSARY IN GREAT STYLE AT THE DORCHESTER ON 9TH MAY Also in this issue: + HSBC Penguin International Coaching Academy in Dubai, South East Asia & the Philippines + PIRFC at the SCC7s, HSBC COBRA 10s & HKFC10s + The COBRA story + + The story behind the Penguin badge & colours + Welcome to the PIRFC Summer Newsletter for 2014 Grove Industries and Tsunami - our sponsors Since the publication of the Autumn Newsletter the We are sure all members HSBC Penguin International Coaching Academy have run will join with us once again highly successful and enjoyable sessions in Dubai, South in expressing our thanks to East Asia and the Phillippines. On the playing front the Grove Industries and Tsunami Penguin International RFC have taken part in the for their continued support, Singapore Cricket Club International 7s, the HSBC interest and sponsorship COBRA International 10s and the GFI Hong Kong of the Penguin International RFC. Football Club International 10s competitions. Penguins XVs have also played their annual fixtures against Oxford and Cambridge Universities. You can read all about these tours and matches later on in these pages. May 2014 did, of course, bring with it our 55th Anniversary Dinner and Grand Reunion held, as usual, at The Dorchester in Park Lane, London. Among our distinguished guests on the night were the Presidents of the Rugby Grove Industries founded in 1983, operates apparel Football Union, the Scottish Rugby Union and sourcing and manufacturing operations on an the Irish Rugby Union. -

Lieutenant Cecil Halliday Abercrombie, Royal Navy, Born At

Lieutenant Cecil Halliday Abercrombie, Royal Navy, born at Mozufferpore, India, on 12 September 1886, was the son of Walter D Abercrombie, Indian Police, and Kate E Abercrombie. In cricket, he was a right hand bat and right hand medium pace bowler. In 1912 he hit 37 and 100 for the Royal Navy v Army at Lord’s. He played for Hampshire Cricket Club in 1913, scoring 126 and 39 in his debut against Oxford University, 144 v Worcestershire and 165 v Essex when Hampshire followed on 317 behind; in a stand with George Brown (140) he put on 325 for the seventh wicket. In first class matches that year he scored 936 runs with an average of 35.92. Between 1910 and 1913, he played six times for Scotland (won 2, lost 4). He was lost with HMS Defence on 31 May 1916, age 29, and is commemorated on the Plymouth Naval Memorial. His widow was Cecily Joan Abercrombie (nee Baker) of 22 Cottesmore Gardens, Kensington, London. (The following is from "The Rugby Roll of Honour" by E H D Sewell, published in 1919) Lieutenant Cecil Halliday Abercrombie, Royal Navy, was born at Mozufferpore, India, on 12 September 1886, and fell in action on HMS Defence at the Battle of Jutland, on May 31, 1916, aged 29. He was educated at Allan House, Guildford, at Berkhamsted School, and on HMS Britannia. He was in the 1st XI and XV, both at school and of the Britannia, and on the training ship won for his Term the High Jump, Long Jump, Racquets, Fives, and Swimming, thus early his versatility proving the shadow of the coming event. -

Rugby Football Union

RUGBY FOOTBALL UNION ·ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING held at the MAY FAffi HOTEL,. LONDON, on Friday, 22nd June, 1951, at 5 p.rn. The following Clubs (330) were represented :- Aldershot Services Christ's Hospital Hertfordshire Union' Army Rugby Union Civil Service Honourable Artillery Company RA.S.C. (Aldershot) Civil Service Union Hoover Sports 9 Trng. Regt. R.E. Clifton Ibis RM.A. Sandhurst College of Commerce Ilford Wanderers No. 4 (ARMT) Trng. Btn. College of St. Mark & St. John Ipswich Y.M.C.A. R.E.M.E. -Cornwall Count,Y' ~Jersey -- - .~~-~~~- 10 Trades Trng. Centre Coventrians Kenilworth 14/20 King's Hussars Coventry Kent County 16 Railway Trng. Regt. R.E. Cuaco Kersal Military College of Science Darlington Railway King Edward VI School, Depot & T.E. R.A.M.C. Davenport Nuneaton RA.P.C. Trng. Centre Derby . Kingsbridge . Ashford (Kent) Derbyshire King's College Hospital Aston O.E. Devon County· King' s College (London) Bancroft's School Devonport High School K.C.S. Old Boys Bank of England Devonport Services King' s College School Barbarians Dorset & Wilts Union Lancashire Barclays Bank Dulwich College Prep. School Leamington Barking ~ark Mod. Old Boys Durham County Leicester Barnstaple Ealing Lensbury Basingstoke Earlsdon Letchworth Bath Eastbourne College Lewes Beckenham Eastern Counties Lizards Bec. O.B. East Midlands Union Lloyds Bank Bedford Esher London & Home Counties Berkshire Union Exeter Schools Billingham Falmouth Grammar School O.B. London Irish Birkenhead Park Falmouth Y.M.C.A. London Scottish Bishopston . Felixstowe London Telecommunications Blackburn Finchley London Union " Blacklieath -~_:, ~Gar.goyles·:"'---- -.. ,- . bondon . Welsh-....."..-~ .-....... '.,' Borderers General Electric Co. -

Tennent's East Regional Reserve League Division 1 (Men's)

Tennent's East Regional Reserve League Division 1 (Men's) 11 September 2021 Selkirk RFC 2nd XV (Men) v Musselburgh RFC 2nd XV (Men) Edinburgh Academical FC 2nd XV (Men) v Jed-Forest RFC 2nd XV (Men) Biggar RFC 2nd XV (Men) v Hawick RFC 2nd XV (Men) Stewart's Melville RFC 2nd XV (Men) v Boroughmuir 2nd XV (Men) Currie Chieftains 2nd XV (Men) v Heriot's Rugby Club 2nd XV (Men) 18 September 2021 Musselburgh RFC 2nd XV (Men) v Edinburgh Academical FC 2nd XV (Men) Hawick RFC 2nd XV (Men) v Selkirk RFC 2nd XV (Men) Jed-Forest RFC 2nd XV (Men) v Stewart's Melville RFC 2nd XV (Men) Currie Chieftains 2nd XV (Men) v Biggar RFC 2nd XV (Men) Heriot's Rugby Club 2nd XV (Men) v Boroughmuir 2nd XV (Men) 25 September 2021 Stewart's Melville RFC 2nd XV (Men) v Musselburgh RFC 2nd XV (Men) Selkirk RFC 2nd XV (Men) v Currie Chieftains 2nd XV (Men) Boroughmuir 2nd XV (Men) v Jed-Forest RFC 2nd XV (Men) Edinburgh Academical FC 2nd XV (Men) v Hawick RFC 2nd XV (Men) Biggar RFC 2nd XV (Men) v Heriot's Rugby Club 2nd XV (Men) 02 October 2021 Musselburgh RFC 2nd XV (Men) v Boroughmuir 2nd XV (Men) Biggar RFC 2nd XV (Men) v Selkirk RFC 2nd XV (Men) Currie Chieftains 2nd XV (Men) v Edinburgh Academical FC 2nd XV (Men) Hawick RFC 2nd XV (Men) v Stewart's Melville RFC 2nd XV (Men) Heriot's Rugby Club 2nd XV (Men) v Jed-Forest RFC 2nd XV (Men) 09 October 2021 Jed-Forest RFC 2nd XV (Men) v Musselburgh RFC 2nd XV (Men) Edinburgh Academical FC 2nd XV (Men) v Biggar RFC 2nd XV (Men) Boroughmuir 2nd XV (Men) v Hawick RFC 2nd XV (Men) Stewart's Melville RFC 2nd XV (Men) -

Scottish Rugby Annual Report 2013/14 Scottish Rugby BT Murrayfield, Edinburgh EH12 5PJ Tel: 0131 346 5000 Scottishrugby.Org | @Scotlandteam

Scottish Rugby Annual Report 2013/14 Scottish Rugby BT Murrayfield, Edinburgh EH12 5PJ Tel: 0131 346 5000 scottishrugby.org | @scotlandteam To download a copy of the Annual Report, please visit scottishrugby.org/annualreport Photo: A GHK youngster getting to grips with the game Contents 2 President’s Welcome 4 Chairman’s Review 6 Chief Executive’s Report The Way Forward 10 Academies 16 Women’s & Girls’ Rugby 20 Coaching Pathways 24 Clubs 30 Schools & Youth 36 Performance Rugby 42 Glasgow Warriors 44 Edinburgh Rugby 46 Referees 48 Commercial Operations, Communications & Public Affairs 50 Working with Government 52 Corporate Social Responsibility 54 Social Media 56 Health & Safety 58 Scottish Rugby Board 60 Strategic Report 62 Board Report 64 A Year of Governance Financial Statements 70 Auditors Report 74 Inc/Exp Account 75 Balance Sheet 76 Cash Flow 77 Notes 83 Five Year Summary 84 Commentary 1 Summer camps like Edinburgh Rugby’s at BT Murrayfield inspire a new generation President’s Welcome It has been an enormous privilege and an exciting time to serve as the Donald Macleod President of the Scottish Rugby Union for the past season. Building on the Strategic Plan of 2012, a policy document, The Way Forward, was presented in December 2013, which outlined initiatives focusing on clubs, schools, coaching pathways, academies and the women’s game. Work is already underway in many of these areas, particularly the last mentioned, where a head of women’s rugby has been appointed to lead developments, while staffing, locations and structures are being identified as I write for the four regional academies. -

Royal Engineers Journal

THE ROYAL ENGINEERS JOURNAL Vol LXXXVI DECEMBER 1972 No 4 Published Quarterly by The Institution of Royal Engineers, Chatham, Kent Telephone: Medway (0634) 42669 Printers W & J Mackay Limited Lordswood Chatham Kent Telephone: Medway (0634) 64381 -^ - INSTITUTION OF RE OFFICE COPY DO NOT REMOVE y ___ ..I I-I /l THE COUNCIL OF THE INSTITUTION OF ROYAL ENGINEERS (Established 1875, Incorporated by Royal Charter, 1923) Patron-HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN President Major-General Sir Gerald Duke, KBE, CB, DSO, BA, C Eng, FICE, DL .. ... 1970 Vce-Presidents Major-General F.G. Caldwell, OBE, MC* ....... ... ... ... ... 1970 Brigadier M. L Crosthwait, MBE, MA, C Eng, MICE, MBIM ... ........ 1970 Elected Members Colonel B.A. E. Maude, MBE, MA ... ... ... ... ... ... 1968 .) Colonel J. R. de G. Plikington, OBE, MC, BSc, C Eng, MICE ... ... 1968 Colonel W. C. S. Harrlson, CBE, ERD, ADC, C Eng, FICE, MIHE ... 1970 Brigadier A. E. Arnold, CBE, BSc ... ............. ... 1970 Brigadier B. C. Elgood, MBE, BA ... ... ... ... ... ... 1970 Brigadier P.J. M. Pellereau, MA, C Eng, FIMechE, MBIM ... ...... 1970 Major W. M. R. Addison, RE, BSc .. ... ..... ...... 1970 Major D. McCarthy, MM, RE, AMBIM . ... ...... 1970 Captain T. R.Kirkpatrick RE, BSc, (Eng) ... ... ... ... ... 1971 Brigadier J.D.Walker, OBE ...... ... ... ... 1972 Ex-Officlo Members Brigadier G. T. E. Westbrook, OBE ....... .. ... .. .. D/E-n-C Colonel H. R. D. Hart, BSc, MBIM ........ ..... AAG RE Brigadier S. E. M. Goodall, OBE, MC, BSc ... ... ... ... ... Comdt RSME Brigadier J. Kelsey, CBE, BSc, ARICS ..... ............... .. D M; Survey Colonel A. H. W. Sandes, MA, C Eng, MICE ... ... ... ... D/Comdt RSME Brigadier P.F. Aylwin-Foster. MA, C Eng, MICE ... ... ... Comd Trg Bde RE Brigadier J. -

Merchiston's Arms

THE MERCHISTONIAN 2017 CLUB MAGAZINE Highland Experience Michael Bremner shares his journey to tourism triumph Savills. Teamwork is one of our core values. Across every area of property, Savills has the right people, the right advice and the right knowledge and our teams work together to ensure that our clients are “Ready Ay Ready” for whatever ball is passed to them. Evelyn Channing Ben Fox Scotland Farms & Estates Edinburgh Residential Savills Edinburgh Savills Edinburgh 0131 247 3704 0131 247 3736 Jamie Macnab Nick Green (Merchistonian 93-98) Scotland Country Houses Rural, Energy and Projects Savills Savills Edinburgh Perth 0131 247 3711 01738 477 518 savills.co.uk 170x240mm Merchistonian A Dec17.qxp_Layout 1 04/12/2017 18:32 Page 3 Welcome From the Merchistonian Office It is with great pleasure that we present to you the 2017 Merchistonian Club Magazine. We have thoroughly enjoyed working on this year’s edition, and hope that you enjoy reading it as much as we enjoyed putting it together. Having edited all of your stories, one thing is clear: the friendships created at Merchiston are strong and lifelong. Thank you for sending us your news, without which there would be no magazine. Please continue to get in touch with any stories throughout the year. A special ‘thank you’ goes out to our advertisers, who make the Left to Right David Rider, Gill Imrie and Louise Pert publication possible, and to our proof readers, who scrupulously check each page. find your nearest rep and remember to send us photos This year has seen the launch of the Club’s new of your get-togethers.