Perceptions of Freedom and the Anti-Vax Movement in Maine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Controversial CFS Researcher Arrested and Jailed - Scienceinsider

Controversial CFS Researcher Arrested and Jailed - ScienceInsider http://news.sciencemag.org/scienceinsider/2011/11/controversial-cfs-researcher-arr.html?ref=em... AAAS.ORG FEEDBACK HELP LIBRARIANS Daily News Enter Search Term ADVANCED ALERTS ACCESS RIGHTS MY ACCOUNT SIGN IN News Home ScienceNOW ScienceInsider Premium Content from Science About Science News Home > News > ScienceInsider > November 2011 > Controversial CFS Researcher Arrested and Jailed Controversial CFS Researcher Arrested and Jailed by Jon Cohen on 19 November 2011, 6:46 PM | 16 Comments Email Print | 0 More PREVIOUS ARTICLE NEXT ARTICLE 1 of 5 12/1/11 10:06 AM Controversial CFS Researcher Arrested and Jailed - ScienceInsider http://news.sciencemag.org/scienceinsider/2011/11/controversial-cfs-researcher-arr.html?ref=em... Judy Mikovits, who has been in the spotlight for the past 2 years after Science published a controversial report by her group that tied a novel mouse retrovirus to chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), is now behind bars. Sheriffs in Ventura County, California, arrested Mikovits yesterday on felony charges that she is a fugitive from justice. She is being held at the Todd Road Jail in Santa Paula without bail. But ScienceInsider could obtain only sketchy details about the specific charges against her. The Ventura County sheriff's office told ScienceInsider that it had no available details about the charges and was acting upon a warrant issued by Washoe County in Nevada. A spokesperson for the Washoe County Sheriff's Office told ScienceInsider that it did not issue the warrant, nor did the Reno or Sparks police department. He said it could be from one of several federal agencies in Washoe County. -

Ketogenic Diet and Immunotherapy in Cancer and Neurological Diseases

American Journal of Immunology Editorials Ketogenic Diet and Immunotherapy in Cancer and Neurological Diseases. 4th International Congress on Integrative Medicine, 1, 2 April 2017, Fulda, Germany 1Thomas Peter and 2Marco Ruggiero 1Therapy Center Anuvindati, Bensheim, Germany 2Silver Spring Sagl, Arzo-Mendrisio, Switzerland Article history Abstract: In this Meeting Report, we review proceedings and comment Received: 23-08-2017 on talks given at the 4 th International Congress on Integrative Medicine Revised: 23-08-2017 Accepted: 25-09-2017 held on April 1 and 2, 2017, in Fulda, Germany. The Theme this year was “Ketogenic Diet and Immunotherapy in Cancer and Neurological Diseases.” Corresponding Author: Speakers came from Europe and the United States and the Congress was Marco Ruggiero attended by more than 100 interested parties from all over the world. Silver Spring Sagl. Via Raimondo Rossi 24, Arzo- Mendrisio 6864, Switzerland Keywords: Ketogenic Diet, Immunotherapy, Integrative Medicine, Email: [email protected] Cancer, Autism, Lyme Disease Introduction a talk entitled "Exploiting cancer metabolism with th ketosis and hyperbaric oxygen". Dr. Poff lectured on the The 4 International Congress on Integrative synergism between nutritional ketosis and hyperbaric Medicine, was held on 1 and 2 April, 2017, in Fulda, oxygen in reducing tumor burden in experimental Germany. The theme of this Congress was "Ketogenic animals and offered insights on the mechanism of action Diet and Immunotherapy in Cancer and Neurological of ketone bodies in a variety of conditions from seizures Diseases" (Ketogene Ernährung und Immuntherapie bei to cancer proliferation. The role of exogenous ketone Krebs und Neurologischen Erkrankungen). bodies in counteracting cancer cell proliferation even in The Congress brought together researchers from all the absence of carbohydrate restriction was also over the world to share their views and research on the discussed. -

Journalism, Truth and Healthy Communities

Journalism, Truth and Healthy Communities Healthy people, healthy businesses, healthy governments — healthy communities — are all best informed and engaged by independent community journalists who examine school budgets, expose scandals, question practices and politics, scrutinize environmental practices, who champion good and who dare to challenge fear and falsehoods. The work we do in our newsrooms enhances community life, it exposes mental and social health care problems and brings solutions forward, it relentlessly exposes overspending in our governments, and highlights the great people who live and work all around us. Communities are healthier, more engaged, more resilient and better able to thrive when informed by truth. The Advertiser-Democrat • Aroostook Republican • The Bethel Citizen • Boothbay Register • The Bridgton News • The Calais Advertiser • The Camden Herald • Castine Patriot • Coastal Journal • County Wide Newspaper • The Courier-Gazette • The Ellsworth American • The Forecaster • The Franklin Journal • Houlton Pioneer Times • Island Ad-Vantages • The Lincoln County News • Livermore Falls Advertiser • Machias Valley News • Observer • Mount Desert Islander • The Original Irregular • The Penobscot Times • The Piscataquis Observer • The Quoddy Tides • The Rangeley Highlander • Rumford Falls Times • St. John Valley Times • The Star-Herald • The Weekly Packet • Wiscasset Newspaper • York County Coast Star • York Weekly Fiddlehead Focus • Penobscot Bay Pilot • Pine Tree Watch A year ago, Carlene Gray suffered a stroke and now every time the 82-year- old tries to climb down the five steps to her yard, it’s a harrowing experience. The boards wobble beneath her. She clutches the railing in fear and hangs on to whomever is there to help. “Somebody has to be with her,” said Hope Priola, Gray’s granddaughter. -

Case 1:21-Cv-00756 ECF No. 1, Pageid.1 Filed 08/27/21 Page 1 of 49

Case 1:21-cv-00756 ECF No. 1, PageID.1 Filed 08/27/21 Page 1 of 49 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN JEANNA NORRIS, on behalf of herself ) and all others similarly situated, ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) ) CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT SAMUEL L. STANLEY, JR. ) FOR DECLARATORY AND in his official capacity as President of ) INJUNCTIVE RELIEF Michigan State University; DIANNE ) BYRUM, in her official capacity as Chair ) JURY TRIAL DEMANDED of the Board of Trustees, DAN KELLY, ) in his official capacity as Vice Chair ) of the Board of Trustees; and RENEE ) JEFFERSON, PAT O’KEEFE, ) BRIANNA T. SCOTT, KELLY TEBAY, ) and REMA VASSAR, in their official ) capacities as Members of the Board of ) Trustees of Michigan State University, ) and JOHN and JANE DOES 1-10, ) ) Defendants. ) Plaintiff and those similarly situated, by and through their attorneys at the New Civil Liberties Alliance (“NCLA”), hereby complains and alleges the following: INTRODUCTORY STATEMENT a. By the spring of 2020, the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, which can cause the disease COVID-19, had spread across the globe. Since then, and because of the federal government’s “Operation Warp Speed,” three separate coronavirus vaccines have been developed and approved more swiftly than any other vaccines in our nation’s history. The Food and Drug Administration (“FDA”) issued an Emergency Use Authorization (“EUA”) for the Pfizer- 1 Case 1:21-cv-00756 ECF No. 1, PageID.2 Filed 08/27/21 Page 2 of 49 BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine (“BioNTech Vaccine”) on December 11, 2020.1 Just one week later, FDA issued a second EUA for the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine (“Moderna Vaccine”).2 FDA issued its most recent EUA for the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 Vaccine (“Janssen Vaccine”) on February 27, 2021 (the only EUA for a single-shot vaccine).3 b. -

Aow 1920 37 Coronavirus Infodemic

1. Mark your confusion. 2. Show evidence of a close reading. 3. Write a 1+ page reflection. The Coronavirus Infodemic How the coronavirus sparked a tsunami of misinformation. Here's everything you need to know. Source: TheWeek.com, May 17, 2020 What's being said? Social media has been awash in lies, rumors, and distortions about the coronavirus, its origins, and potential cures almost since the pandemic's start. NewsGuard, a private company that rates websites' reliability, has identified 203 websites throughout the world promoting COVID-19 misinformation. Among the most popular COVID-19 myths were "Garlic can cure COVID-19," "A group funded by Bill Gates patented the coronavirus," and "The COVID-19 virus is a man- made bioweapon." The World Health Organization is calling the deluge of misinformation "an infodemic," while Google, Facebook, and Twitter are instituting policies to help slow the spread of lies. CEO Mark Zuckerberg's Facebook fact-checkers have "taken down hundreds of thousands of pieces of misinformation," and slapped warnings on 40 million posts during March alone, the company says. Last week, YouTube removed a video titled "Plandemic" that had been viewed millions of times, featuring discredited microbiologist and anti-vaxxer Judy Mikovits. In the video and a book that reached No. 1 on Amazon, Mikovits contends the coronavirus was created and spread by a conspiracy of wealthy people and scientists such as Dr. Anthony Fauci, head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, to bolster vaccine rates and make money. Mikovits has been claiming her career was destroyed by Fauci and other scientists since she falsely reported in a 2009 study, later retracted by the journal that published it, that a retrovirus caused chronic fatigue syndrome. -

Maine NOW Times (Winter 1994)

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Maine Women's Publications - All Publications Winter 1-1-1994 Maine NOW Times (Winter 1994) National Organization for Women - Maine Chapter Staff National Organization for Women - Maine Chapter Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/maine_women_pubs_all Part of the Women's History Commons Repository Citation Staff, National Organization for Women - Maine Chapter, "Maine NOW Times (Winter 1994)" (1994). Maine Women's Publications - All. 488. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/maine_women_pubs_all/488 This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine Women's Publications - All by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Get Charged Up NOW Chapter Activist’s Day Winthrop Street Unitarian/Universalist Church in Augusta 9:30 until 4:00 Saturday, January 8. M A T I O Rl A L ORGANIZATION FOR WOMEN There is no charge, but donations will be accepted to help defray costs. Soup, bread and beverages will be provided for lunch. You can bring other food to share, if you wish. Preregistration is required! To preregister, call Cynthia Phinney at 778-9506 and leave your name, address, and phone number on the machine. Preregistraions before December 24 will be greatly appreciated, though registrations will be accepted until MAINE January 6. “The purpose of NOW is to take action to bring women into NOW full participation in the mainstream of American society now, exercising all the privileges and responsibilities thereof in truly equal partnership with men.” The heart of NOW is in activism, and the ranks of our TIMES membership run the gamut from longtime seasoned activists, to those who are just beginning to consider expanding the ways and WINTER 1994 the places they act on their feminist principles. -

Film Flub; Diversity Deficiency

Spectrum | Autism Research News https://www.spectrumnews.org SPOTTED New numbers; film flub; diversity deficiency BY KATIE MOISSE 1 APRIL 2016 WEEK OF MARCH 28TH New numbers After ticking up since 2000, the rate of autism among 8-year-olds in the U.S. may be leveling off. One in 68 school-age children have autism, according to data released yesterday by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The same rate was reported in 2014, marking a possible plateau in autism prevalence. The CDC cautions, however, that it’s too soon to tell whether the rate is truly stabilizing. Late last year, the agency reported that 1 in 45 children have autism, based on a different surveillance method. Prevalence also varies dramatically between states, with New Jersey reporting a rate of 1 in 41 compared with Maryland’s 1 in 123. SOURCES: U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention / 31 Mar 2016 CDC estimates 1 in 68 school-aged children have autism; no change from previous estimate http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2016/p0331-children-autism.html Film flub First it was on, then it was off. Now it’s back on again. “Vaxxed: From Cover-Up to Catastrophe,” a film directed by the disbarred doctor Andrew Wakefield, will debut today at New York City’s Angelika Theater. 1 / 4 Spectrum | Autism Research News https://www.spectrumnews.org It’s not the venue the film’s makers had hoped for. “Vaxxed” was slated to premier at the prestigious Tribeca Film Festival, co-founded by actor Robert de Niro, who says he has a son with autism. -

SCR-71 Submitted On: 3/18/2021 10:06:08 PM Testimony for PSM on 3/23/2021 1:10:00 PM

SCR-71 Submitted on: 3/18/2021 10:06:08 PM Testimony for PSM on 3/23/2021 1:10:00 PM Testifier Present at Submitted By Organization Position Hearing Isabel Espiritu Individual Oppose No Comments: Aloha, We the people of Hawaii do not want Resolution SCR71 to pass. We should be able to fly without showing any proof of any medical records. This is medical discrimination, unethical and a direct violation on our constitutional rights. SCR-71 Submitted on: 3/22/2021 4:12:11 AM Testimony for PSM on 3/23/2021 1:10:00 PM Testifier Present at Submitted By Organization Position Hearing Lily Gavri Individual Oppose No Comments: Everything that is going on with Covid as well as the entire medical and pharmaceutical industry is built on the germ theory of disease by Louis Pasteur which proposes that particles in the air are the cause of disease. This has never been proven in accordance with Koche’s postulates which are the principles by which microorganisms are scientifically identified and isolated. They are: 1. The microorganism must be identified in all individuals affected by the disease, but not in healthy individuals. 2. The microorganism can be isolated from the diseased individual and grown in culture. 3. When introduced into a healthy individual, the cultured microorganism should cause disease. 4. The microorganism must then be re-isolated from the experimental host, and found to be identical to the original microorganism. This has never been done with a virus. What they do when trying to identify a virus is they take a healthy cell, starve and poison it and when it dies they claim the leftover particles of the dead cell are newly formed “viruses” “The CDC has NEVER isolated and purified ANY alleged "virus." They simply isolate certain particles that are a natural part of the human body's processes and place that isolated particle into a petri dish wherein they mix it with monkey kidney cells and chemicals and starve the cell whereby it begins to break down. -

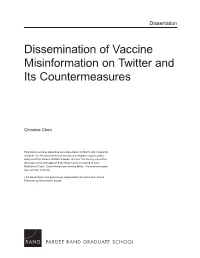

Dissemination of Vaccine Misinformation on Twitter and Its Countermeasures

Dissertation Dissemination of Vaccine Misinformation on Twitter and Its Countermeasures Christine Chen This document was submitted as a dissertation in March 2021 in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the doctoral degree in public policy analysis at the Pardee RAND Graduate School. The faculty committee that supervised and approved the dissertation consisted of Luke Matthews (Chair), Sarah Nowak and Jeremy Miles. The external reader was Jennifer Golbeck. This dissertation was generously supported by the Anne and James Rothenberg Dissertation Award. PARDEE RAND GRADUATE SCHOOL For more information on this publication, visit http://www.rand.org/pubs/rgs_dissertations/RGSDA1332-1.html Published 2021 by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. is a registered trademarK Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademarK(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is reQuired from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions.html. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help maKe communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND MaKe a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Abstract Outbreaks of vaccine preventable diseases have continued to affect many parts of the United States. -

Pennington to Lead Student Body

PAGE 2 • NEWS PAGE 7 • ARTS PAGE 16 • FEATURES During hybrid learning, Head designer of the Check out reviews of three many teachers have sneaker shop Leaders chicken sandwiches from struggled to find a 1354, alumnus Ellen Ma around Chicago. Find balance where both in- uses her platform to out how factors such as person and distance connect Asian and Black presentation, freshness, learning students remain communities in Chicago crispiness and flavor can engaged in class. through streetwear. make or break the taste. University of Chicago Laboratory High School 1362 East 59th Street, Chicago,U-HIGH Illinois 60637 MIDWAY uhighmidway.com • Volume 97, Number 2 MAY 6, 2021 Editors Pennington to lead student body by AMANDA CASSEL With a relatively low voter EDITOR-IN-CHIEF 2021-22 Student Council turnout this year, do you think sign off This interview took place May 1, Student Council is representative President: Brent Pennington the day after the election, and was of the entire student body? Kennedi Bickham lightly edited for clarity and space. Vice President: Student Council is 23 people year of The extended version is online. Secretary: Peter Stern representing 610 students. There What is your main goal or a Treasurer: Taig Singh is no way in the world that Student couple of your main goals as all- Cultural Union President: Council is going to be able to rep- distance school president. How do you Saul Arnow resent that many people with just plan to put them into action? Cultural Union Vice President: 23 people, which is why I want to by EDITORS-IN-CHIEF My main goal as all-school pres- make sure that Student Council is Katie Baffa Dear Readers, ident is to make it so that Student open to having people who either Fourteen months ago, life Council is capable of accomplish- CLASS OF 2022 didn’t win or just didn’t run at all to changed: from classes to ing a lot and to prove to the rest of President: Zachary Gin come on Student Council and rep- clubs to sports. -

Location of Somerset County Maine Newspapers 1998 Janet Roberts

Maine State Library Maine State Documents Reader & Information Services Division Maine State Library Documents 1998 Location of Somerset County Maine Newspapers 1998 Janet Roberts Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalmaine.com/ris_docs Recommended Citation Roberts, Janet, "Location of Somerset County Maine Newspapers 1998" (1998). Reader & Information Services Division Documents. 15. http://digitalmaine.com/ris_docs/15 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Maine State Library at Maine State Documents. It has been accepted for inclusion in Reader & Information Services Division Documents by an authorized administrator of Maine State Documents. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LOCATION OF SOMERSET COUNTY TITLES May 13, 1999 Where Can I Find Somerset County Papers? Lincoln County Newspapers Held by Maine Repositories, sorted by title. Holdings catalogued by the Maine Newspaper Project, Maine State Library This is a preliminary list, which does not show the extent of each repository's holdings. A site may have only a single issue of any particular paper. The tina I list will show the holdings. Brackets around the place of publication means that the location was not given in the masthead, but is evident trom information elsewhere in the paper. or = original fm = microfilm u=unknown 9999=Paper is still being published FORMAT DATES PUBLISHED OCLC NUMBER Bingham herald Fairfield 18uu to 19uu 33372919 Maine Historical Society or Carney Brook chronicle Binaham 1994 to 1998 40552295 Maine State Library or Clarion (Skowhegan, Me.) Skowheaan 18uu to 1uuu 33372952 Maine Historical Society or Democratic clarion Skowheaan 1841 to 1857 9439999 Banoor Historical Society or Banoor Public Library or Bowdoin Colleoe Library or Maine Historical Society or Maine State Library or Skowheoan Historic House Assoc. -

Vaccines and ME

Vaccines and M.E. – something to consider for the Covid 19 vaccines February 2021 Vaccines in general Many M.E. sufferers will be wondering whether to have the Covid 19 vaccinations; whilst I have no medical qualifications, I would like nevertheless to share some reflections on both general vaccines and information so far gathered specifically on the Covid 19 vaccinations. The effects of vaccines are always risky for M.E. sufferers due to an abnormally functioning immune system in the first placei. For some sufferers their M.E. was triggered by a vaccine: this happened tragically to Lynn Gilderdale aged 14 after the school BCG vaccination.ii I personally remember suffering a relapse of M.E. when I was 16 after receiving the BCG vaccination at school, back in 1980. There have been enough reports of M.E. being triggered by vaccines to prompt a patient survey by the M.E. Association in 2010, with Hepatitis B being reported as the main vaccine trigger for M.E. iii In the USA, a court of law in 2013 ruled that a Hepatitis B vaccine caused a person’s Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. iv Quote by Dr. Charles Shepherd: ‘Anecdotal evidence indicates that a number of vaccinations are occasionally capable of either triggering ME/CFS, or causing an exacerbation of pre-existing symptoms, and the UK CMO Working Group report acknowledged (in section 3.3.2) that vaccinations can occasionally act as a trigger factor in the development of ME/CFS.’v Some of you may have heard of the short film Plandemic where Dr.