Bustin, David W. Oral History Interview Andrea L'hommedieu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2011-Summer.Pdf

BOWDOIN MAGAZINE VOL. 82 NO. 2 SUMMER 2011 BV O L . 8 2 N Oow . 2 S UMMER 2 0 1 1 doin STANDP U WITH ASOCIAL FOR THECLASSOF1961, BOWDOINISFOREVER CONSCIENCE JILLSHAWRUDDOCK’77 HARI KONDABOLU ’04 SLICINGTHEPIEFOR THE POWER OF COMEDY AS AN STUDENTACTIVITIES INSTRUMENT FOR CHANGE SUMMER 2011 CONTENTS BowdoinMAGAZINE 24 AGreatSecondHalf PHOTOGRAPHS BY FELICE BOUCHER In an interview that coincided with the opening of an exhibition of the Victoria and Albert’s English alabaster reliefs at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art last semester, Jill Shaw Ruddock ’77 talks about the goal of her new book, The Second Half of Your Life—to make the second half the best half. 30 FortheClassof1961,BowdoinisForever BY LISA WESEL • PHOTOGRAHS BY BOB HANDELMAN AND BRIAN WEDGE ’97 After 50 years as Bowdoin alumni, the Class of 1961 is a particularly close-knit group. Lisa Wesel spent time with a group of them talking about friendship, formative experi- ences, and the privilege of traveling a long road together. 36 StandUpWithaSocialConscience BY EDGAR ALLEN BEEM • PHOTOGRAPHS BY KARSTEN MORAN ’05 The Seattle Times has called Hari Kondabolu ’04 “a young man reaching for the hand-scalding torch of confrontational comics like Lenny Bruce and Richard Pryor.” Ed Beem talks to Hari about his journey from Queens to Brunswick and the power of comedy as an instrument of social change. 44 SlicingthePie BY EDGAR ALLEN BEEM • PHOTOGRAPHS BY DEAN ABRAMSON The Student Activity Fund Committee distributes funding of nearly $700,000 a year in support of clubs, entertainment, and community service. -

Maisel, L. Sandy Oral History Interview Andrea L'hommedieu

Bates College SCARAB Edmund S. Muskie Oral History Collection Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library 4-5-2000 Maisel, L. Sandy oral history interview Andrea L'Hommedieu Follow this and additional works at: http://scarab.bates.edu/muskie_oh Recommended Citation L'Hommedieu, Andrea, "Maisel, L. Sandy oral history interview" (2000). Edmund S. Muskie Oral History Collection. 233. http://scarab.bates.edu/muskie_oh/233 This Oral History is brought to you for free and open access by the Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library at SCARAB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Edmund S. Muskie Oral History Collection by an authorized administrator of SCARAB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Interview with L. Sandy Maisel by Andrea L’Hommedieu Summary Sheet and Transcript Interviewee Maisel, L. Sandy Interviewer L’Hommedieu, Andrea Date April 5, 2000 Place Waterville, Maine ID Number MOH 182 Use Restrictions © Bates College. This transcript is provided for individual Research Purposes Only ; for all other uses, including publication, reproduction and quotation beyond fair use, permission must be obtained in writing from: The Edmund S. Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library, Bates College, 70 Campus Avenue, Lewiston, Maine 04240-6018. Biographical Note Louis “Sandy” Maisel was born on October 25, 1945 in Buffalo, New York. Maisel attended Harvard where he became involved with various campus and political organizations. Maisel went on to attend Columbia for his graduate work, where he received his Ph.D. in Political Science. In 1971, he settled in Maine, working on Bill Hathaway’s campaign for Senate and teaching at Colby College. -

Archives Provide Glimpses of the Past FIRST IMPRESSION

UMaineCREATIVITY AND ACHIEVEMENT AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MAINETodaySEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2004 What did they see? Archives provide glimpses of the past FIRST IMPRESSION From the President THE UNIVERSITY OF WITH ITS 3,500 MILES of coastline, Maine has always been MAINE inextricably linked to the sea. Shell middens provide clues to how early peoples interact ed with the marine environm ent. UMaineToday Archival records reveal how Europeans first explored the coast, Publisher sea captains and boatbuilders made their livings, and fishermen Jeffery N. Mills plied their trade. Vice President for Universi ty Advancement Despite such a long history; we are still looking for greater Executive Director of Public Affairs and und erstanding of our oceans, including the effect of human s on Marketing the marine environment. Today, it's particularly urgent because Luanne M. Lawrence our oceans are in crisis, as demonstrated by recent reports from Director of Public Affairs th e U.S. Commission on Ocean Policy and the Pew Oceans Joe Carr Commission. A numb er of abundant fisheries have crashed, Editor although some show signs of recovery. Ocean poli cies must Margaret Nagle respond to multiple pressures, includin g industrial development and homeland security Contributing Wri ters and Associates Carrie Bulduc, Joe Carr, Nick Houtman, concerns. Kay Hyatt, George Manlove, Margaret Nagle, Researchers around the globe are racing to contribute information through basic and Chris topher Smith applied science to ensure that our marine environments remain sustainable, economically Designers viable and safe. At the University of Maine, we are expanding our long-standing marine Michael Mardosa, Carol Nichols, Valerie Williams sciences and aquaculture research efforts. -

Maine Law Magazine Law School Publications

University of Maine School of Law University of Maine School of Law Digital Commons Maine Law Magazine Law School Publications Fall 2014 Maine Law Magazine - Issue No. 90 University of Maine School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mainelaw.maine.edu/maine-law-magazine Part of the Law Commons This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Publications at University of Maine School of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine Law Magazine by an authorized administrator of University of Maine School of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maine Law Magazine Parents in Law The art of balancing studies & children Inside Capitol Connection Maine Law’s D.C. links run deep Clinical Practice One student’s story THE UNIVERSITY OF MAINE SCHOOL OF LAW / FALL 2014 OPENING ARGUMENTS John Veroneau Partner, Covington & Burling LLP John Veroneau, a 1989 graduate of Maine Law, is co-chair of the International Trade and Finance group at Covington & Burling in Washington D.C. He served as Deputy U.S. Trade Representative (2007-2009) and previously as USTR’s general counsel, as Assistant Secretary of Defense in the Clinton Administration, as Chief of Staff to Senator Susan Collins, and as Legislative Director, respectively, for Senators Bill Cohen and Bill Frist. What lessons do you recall best from your law What have you found most satisfying about your school education? wide-ranging career? I long ago forgot the Rule against Perpetuities Probably the variety of experiences and the people but will forever remember Mel Zarr’s brilliant I’ve worked with. -

Winter10 Entiremag.Pdf

UNIVERSITY OF NEW ENGLAND MAGAZINE WINTER 2010 CREATINGBuilding Connections.Community For Life. Expanded facilities engage students in campus life SUMMER 2009 CONNECTION ALUMNI AND FRIENDS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW ENGLAND, WESTBROOK COLLEGE A& ST. FRANCIS COLLEGE FORFOR ALUMNI ALUMNI & & FRIENDS FRIENDS OF OF THE THE UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY OF OF NEW NEW ENGLAND, ENGLAND, WESTBROOK WESTBROOK COLLEGE COLLEGE AND AND ST. ST. FRANCIS FRANCIS COLLEGE COLLEGE UNIVERSITY OF NEW ENGLAND 1 PRESIDENT’S LETTER 2010 REFLECTIONS THIS SEASON IS A TIME FOR REFLECTION, RECOGNIZING ACCOMPLISHMENTS AND EXPRESSING GRATITUDE, AND LOOKING FORWARD TO THE YEAR AHEAD. President Danielle N. Ripich, Ph.D. s I reflect upon 2010, I am particularly grateful for UNE is becoming a truly global university. This year we the many achievements of our students, faculty, and established the position of Associate Provost for Global Initia- the university. We are making significant progress tives and are partnering with institutions around the world to A toward our Vision 2017 strategic plan goals. expand educational opportunities for our students. UNE UNE’s enrollment is now over 6,800, with more students students have traveled to Ghana, Brazil, Kenya, and Peru. transferring into the university than ever before. Our Our students are raving about the $26 million campus incoming student body, both undergrads and grads, now expansion in Biddeford that includes our beautiful new 300-bed represent 26 states and 12 countries. UNE welcomed 698 Sokokis Residence Hall and a state-of-the-art synthetic blue turf incoming freshman students (a 10.6 percent increase) and field for our athletic teams. -

Unpopular Lepage in Danger for 2014 Re-Election

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE January 22, 2013 INTERVIEWS: Tom Jensen 919-744-6312 IF YOU HAVE BASIC METHODOLOGICAL QUESTIONS, PLEASE E-MAIL [email protected], OR CONSULT THE FINAL PARAGRAPH OF THE PRESS RELEASE Unpopular LePage in danger for 2014 re-election Raleigh, N.C. – Republican Paul LePage is in danger of losing his bid for re-election unless the 2014 Maine governor’s contest turns out to be the same sort of three-way race that paved the way for LePage’s victory in 2010. PPP’s latest poll finds LePage ahead by 4 to 7 points in every potential three-way contest while losing every head-to-head contest by 8 to 21 points. If LePage and independent Eliot Cutler were the only two candidates, Cutler would lead LePage 49% to 41%. But in every three-way scenario, Cutler’s strength as an independent candidate gives LePage the lead over their possible Democratic opponents. LePage’s job approval rating is significantly underwater at -16, with 39% approving and 55% disapproving. 18% of Republicans and 54% of independents disapprove of the job that LePage is doing as governor. “Paul LePage’s chances at reelection appear contingent on there being both a strong Democratic candidate and a strong independent candidate on the ballot next year,” said Dean Debnam, President of Public Policy Polling. “He would have very little chance in a race against just one serious opponent.” John Baldacci is the favorite of Democratic primary voters with 28% support, followed by Chellie Pingree (21%), Mike Michaud (19%), Emily Cain (6%), Janet Mills (4%), Ethan Strimling (3%) and Jeremy Fischer (2%). -

Thirty Years of Economic Development in Maine

____________________________________________________________________________________ IN SEARCH OF SILVER BUCKSHOT: THIRTY YEARS OF ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN MAINE Laurie Lachance Maine Development Foundation Augusts ME 04330 [email protected] A Background Paper Prepared for the Brookings Institution Metropolitan Policy Program in support of its larger project, “Charting Maine’s Future: An Action Plan for Promoting Sustainable Prosperity and Quality Places” October 2006 Note: The views expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect those of either the trustees, officers, or staff members of the Brookings Institution; GrowSmart Maine; the project’s funders; or the project’s steering committee. The paper has also not been subject to a formal peer review process. ____________________________________________________________________________________ i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author wishes to thank to all of the many individuals who gave hours of their time to share their honest assessment of the many economic-development policies and programs that have shaped Maine’s growth and their insights as to the bold actions we must take in the future. Below are the many individuals who provided interviews, critical data and background information, or thoughtful responses to an email survey: Interviewees Joseph Wischerath, Former CEO of Maine & Co. Gov. John E. Baldacci Mark Woodward, Bangor Daily News Gov. Joseph E. Brennan Janet Yancey-Wrona, Dept. of Economic & Gov. Kenneth M. Curtis Community Devevelopment Gov. Angus S. King, Jr. Provided reports, information, and data Stephen Adams, U.S. Small Business Dennis Bergeron, Public Utilities Commission Administration Betsy Biemann, Maine Technology Institute Richard Batt, Franklin Community Health Network Jim Breece, University of Maine System William Beardsley, Husson College Suzan Cameron, Department of Education Sandy Blitz, Bangor Target Area Dev. -

2009-Winter.Pdf

Happy Holidays & UNIVERSITYOFMAINE Happy New Year COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING December 2009 Newsletter In This Issue: Three Offshore Wind-power Test Sites Unveiled for Maine AUGUSTA, Maine — Government officials and researchers who seek to build ocean-based wind NEWS and wave turbines in the Gulf of Maine unveiled three sites where prototypes will be constructed. Three off-shore Wind Power Test Sites Unveiled This announcement puts Maine one step closer to becoming the first state in the nation to cre- for Maine ate off-shore wind test and demonstration sites, which according to University of Maine profes- sor Habib Dagher will position the state at the forefront of Professor Vetelino a widespread effort to tap renewable energy sources. Named IEEE Fellow Improving Early Cancer “Our vision is to put Maine in front of the country and the Detection world in the development of offshore wind power,” said Dagher, who as director of the university’s Advanced Struc- Professor Worboys Selected tures and Composites Center plans to conduct research with for National Research three wind turbines at one of the locations. Council The three sites, selected by a consortium of government and Hall Makes Ten-Year private agencies, include one off Boon Island, near the south- Committment to UMaine ern Maine town of York; one off Damariscove Island near the town of Boothbay; and the third near Monhegan Island, EVENTS located some 25 miles from Maine’s midcoast region. All Engineering Job Fair three sites, which measure between 1 and 2 square miles, are Dana’s Picnic on the Farm in Maine’s territorial waters, which means the state — as op- posed to the federal government — will retain regulatory au- James and Maureen thority. -

Maine Alumni Magazine, Volume 89, Number 2, Summer 2008

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine University of Maine Alumni Magazines - All University of Maine Alumni Magazines Summer 2008 Maine Alumni Magazine, Volume 89, Number 2, Summer 2008 University of Maine Alumni Association Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/alumni_magazines Part of the Higher Education Commons, and the History Commons This publication is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Maine Alumni Magazines - All by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Summer 2008 A Life of Conscience and Commitment Nobel Laureate Bernard Lown ’42 visits campus Tapping the Tides Maine research study the potential for tidal power The Soldier/Scholar Remembering Sergeant Nicholas Robertson ’03 I am the Foundation “The University of Maine was the launching pad for Clark and me. I continue to care deeply about the University and want to do my part to help the next generation succeed. ” — Laurie Liscomb ’61 aurieL Liscomb graduated from the University of Maine in 1961 with a degree in Home Economics. It was at the University that Laurie met her husband Clark, class of I960. When Clark passed away in 2003, Laurie established the Clark Noyes Liscomb ’60 Prize in the University of Maine Foundation as a means of encouraging and aiding promising students enrolled in the School of Business to pursue their dreams of a career in international commerce. If you would like to learn more about establishing a scholarship, please call the University of Maine Foundation Planned Giving Staff or visit our website for more information. -

Maine State Legislature

MAINE STATE LEGISLATURE The following document is provided by the LAW AND LEGISLATIVE DIGITAL LIBRARY at the Maine State Law and Legislative Reference Library http://legislature.maine.gov/lawlib Reproduced from scanned originals with text recognition applied (searchable text may contain some errors and/or omissions) Legislative Record House of Representatives One Hundred and Twenty-First Legislature State of Maine Volume III Second Special Session April 8, 2004 - April 30, 2004 Appendix House Legislative Sentiments Index Pages 1563-2203 Legislative Sentiments Legislative Record House of Representatives One Hundred and Twenty-First Legislature State of Maine LEGISLATIVE RECORD - HOUSE APPENDIX December 4, 2002 to November 30, 2004 APPENDIX TO THE LEGISLATIVE RECORD players Elizabeth Bruen, Stephanie Gonzales, Meredith McArdle, 121ST MAINE LEGISLATURE Chelsea Cote, Sara Farnum, Kristina Grimaldi, Ashley Higgins, Whitney Huse, Melissa Joyce, Emily Mason, Lindsay Monn, Dr. Ronald Lott, of Orono, who was presented with Ithe Ashley Beaulieu, Arielle DeRice, Emma Grandstaff, Callan Kilroy, Veterinary Service Award by the Maine Veterinary Medical Hannah Monn, Amanda Wood, Ashley Dragos, Hannah Jansen, Association. The award recognizes his tireless efforts, through Bridget Hester and Christina Capozza; assistant coach Andy the establishment of shelters, to care for unwanted animals. Dr. Pappas; and Head Coach Melissa Anderson. We extend our Lott began his work with stray animals as an intern at Rowley congratulations and best wishes to the team and the school on Memorial Animal Hospital. In 1981, he established Ithe this championship season; (HLS 8) Penobscot Valley Humane Society in Lincoln. Ten years later he the Falmouth "Yachtsmen" High School Boys Soccer Team, founded the Animal Orphanage in Old Town. -

2005 Archive of Governor Baldacciâ•Žs Press

Maine State Library Digital Maine Governor's Documents Governor 2005 2005 Archive of Governor Baldacci’s Press Releases Office of veGo rnor John E. Baldacci Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalmaine.com/ogvn_docs Recommended Citation Office of Governor John E. Baldacci, "2005 Archive of Governor Baldacci’s Press Releases" (2005). Governor's Documents. 16. https://digitalmaine.com/ogvn_docs/16 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Governor at Digital Maine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Governor's Documents by an authorized administrator of Digital Maine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2005 Archive of Governor Baldacci’s Press Releases Compiled by the Maine State Library for the StateDocs Digital Archive with the goal of preserving public access and ensuring transparency in government. 2005 Archive of Governor Baldacci’s Press Releases Table of Contents Governor Directs State Flag to be Flown at Half-Staff .................................................................................. 7 DirigoChoice Coverage Celebrated by Maine Businesses ............................................................................. 8 Governor Introduces Budget ........................................................................................................................ 9 Governor’s Office Releases MaineCare Fact Book ...................................................................................... 11 Governor Introduces Primary Seat Belt Proposal ...................................................................................... -

2007-Fall.Pdf

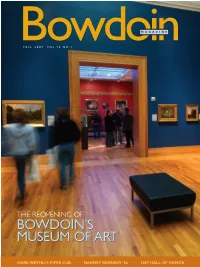

MAGAZINE BowdoinFALL 2007 VOL.79 NO.1 THE REOPENING OF BOWDOIN’S MUSEUM OF ART MARK WETHLI’S PIPER CUB • NANNEY KENNEDY ’82 • 2007 HALL OF HONOR BowdoinMAGAZINE FALL 2007 FEATURES 16 Pictures at an Exhibition: The Reopening of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art 16 BY SELBY FRAME PHOTOGRAPHS BY JAMES MARSHALL AND MICHELE STAPLETON The Museum of Art celebrated its public reopening and its renewed position as the cornerstone of arts and culture at Bowdoin in October, following an ambitious $20.8 million renovation and expansion project. Selby Frame gives us a look at the last stages CONTENTS of the project – the preparation of the exhibitions – as well as a glimpse of the first visitors. 24 Arrivals and Departures BY EDGAR ALLEN BEEM 24 PHOTOGRAPHS BY JAMES MARSHALL Professor of Art Mark Wethli came to Bowdoin in 1985 to direct Bowdoin’s studio art program. In the 22 years since then,Wethli has mentored and inspired countless students and has led Bowdoin in elevating its profile in the state and national art scenes. In addition to discussing Wethli’s most recent project, Piper Cub, Ed Beem writes of the many forms Wethli’s aesthetic vision has taken over the years. 30 30 Craftswoman, Farmer, Entrepreneur BY JOAN TAPPER PHOTOGRAPHS BY GALE ZUCKER Nanney Kennedy ’82, a Bowdoin lacrosse player who earned her degree in the sociology of art, followed her own path from artisan to businesswoman and advocate for sustainability. Joan Tapper, who inter- viewed Kennedy for her upcoming book Shear Spirit: Ten Fiber Farms,Twenty Patterns and Miles of Yarn (Potter Craft:April 2008), tells us how she built new dreams on old foundations.