Billy Atkins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Organize PDF Index at 13;33;19 on 09/17/2016 By; Vilma Winters

Organize PDF Index at 13:33:19 on 09/17/2016 by: Vilma Winters [Time: 13:32:41] !N,C,A,A,Watch. 'Old Dominion Monarchs vs NC State Wolfpack'. Football. Free !N,C,A,A,Watch. 'Old Dominion Monarchs vs NC State Wolfpack'. Football. Free [Time: 13:32:41] ^Yahoo-SportsWatch. 'Liberty Flames vs SMU Mustangs'. Online. Football. On. First. Row ^Yahoo-SportsWatch. 'Liberty Flames vs SMU Mustangs'. Online. Football. On. First. Row [Time: 13:32:41] $Fox-TVWatch. 'Pittsburgh Panthers vs Oklahoma State Cowboys'. Football. Live. Online. Free. P2P $Fox-TVWatch. 'Pittsburgh Panthers vs Oklahoma State Cowboys'. Football. Live. Online. Free. P2P [Time: 13:32:41] ^kick-Off$Watch. 'Ohio State Buckeyes vs Oklahoma Sooners'. Live. Football. Tv. Ru ^kick-Off$Watch. 'Ohio State Buckeyes vs Oklahoma Sooners'. Live. Football. Tv. Ru [Time: 13:32:41] @Fox-TVWatch. 'Michigan State Spartans vs Notre Dame Fighting Irish'. Atdhe. Live. Football. Streaming @Fox-TVWatch. 'Michigan State Spartans vs Notre Dame Fighting Irish'. Atdhe. Live. Football. Streaming [Time: 13:32:41] @Sche-duled%Watch. 'Michigan State Spartans vs Notre Dame Fighting Irish'. Live. Sport. Streaming. Websites @Sche-duled%Watch. 'Michigan State Spartans vs Notre Dame Fighting Irish'. Live. Sport. Streaming. Websites [Time: 13:32:41] !Sky-Sports%Watch. 'Monmouth Hawks vs Kent State Golden Flashes'. Live. Football. Streaming. Online. Pc !Sky-Sports%Watch. 'Monmouth Hawks vs Kent State Golden Flashes'. Live. Football. Streaming. Online. Pc [Time: 13:32:41] @N,C,A,A,!Watch. 'Ohio State Buckeyes vs Oklahoma Sooners'. American. Football. Free. Live. Streaming @N,C,A,A,!Watch. 'Ohio State Buckeyes vs Oklahoma Sooners'. -

January 19, 2018, 9:00 A.M

MINUTES BOARD OF TRUSTEES' MEETING January 19, 2018, 9:00 a.m. Adams Administration Building, Troy University Campus Troy, Alabama The Troy University Board of Trustees convened at 9:00 a.m. on January 19, 2018, in the Chancellor's Conference Room, Adams Administration Building, on the Troy University Campus, Troy, Alabama. Prior to the Call to Order, Senator Dial presented a resolution by the Alabama Legislature commending the 2017 Troy Trojans football team on the occasion of winning its sixth Sun Belt Conference championship and compiling its best PBS season to date. Mr. Tom Davis read the concurrent resolution. Senator Dial recognized Coach Neal Brown and presented the resolution to Coach Brown. Senator Dial expressed appreciation to Marcus Paramore for his efforts in having the resolution drafted. Coach Brown provided brief remarks. Also prior to the Call to Order, Senator Dial recognized SGA President Ashli Morris on the occasion of her engagement. I. Call to Order Board President Pro-tern Gerald Dial called the meeting to order. Senator Dial recognized Doug Gooden with WSFA Television. Mr. Dial welcomed all members and guests, and called for a roll call, with the following members answering present: II. Roll Call Senator Gerald Dial, Mrs. Karen E. Carter, Mr. Ed Crowell, Dr. Roy H. Drinkard, Mr. John D. Harrison, Dr. Earl V. Johnson, Mr. Lamar P. Higgins, Mr. Forrest Latta, Mr. Gibson Vance, Mr. Charles Nailen, Mr. Allen Owen (via phone), and Ms. Ashli Morris, SGA President. III. Approval of Minutes A draft copy of the July 28, 2017 minutes was provided to the Board members prior to the meeting. -

Search Latest News

SEARCH LATEST NEWS Troy Home Privacy Archive TROY POSTED BY EIZ ON THURSDAY, 19 JANUARY, 2012, 7:14 AM GO Troy.png GAME NOTES: Two struggling squads try to climb their way out of the cellar in the Sun Belt Conference standings, as the South Alabama Jaguars welcome the Troy Trojans to the Mitchell Center in Mobile. After a three-game win streak brought Troy to 4-3 ... Share | TROY POSTED BY EIZ ON THURSDAY, 19 JANUARY, 2012, 7:14 AM bovada.net OddsPGA Store|High SchoolHigh School HomeSuper 25 IndexRecruiting|NHLNHL HomeKevin Allen's ColumnsFantasyTeam PagesScoresStandingsStatisticsSchedulesSalary DatabaseInjuriesRostersMinorsBovada.net OddsCovers.com MatchupsCovers.com OddsSheridan's OddsJuniorsTransactionsTV ScheduleDirectoryArchiveNHL StoreNHL tickets |UFCUFC HomeBovada.net Odds|FantasyMLBFantasy Windup blogNFLFantasy Joe blogNBANHLNASCARGolfCollege Football|TicketsTicketsNFL ticketsMLB ticketsNCAAF ticketsNCAAB ticketsNBA ticketsNHL tickets|MoreAction SportsBoxingScheduleWBA RankingsWBC RankingsIBF RankingsChampionsBovada.net OddsSheridan's OddsCyclingHorse Racing MMAOlympicsRecruitingSoccerMLSU.S. SoccerWorld SoccerSalaries DatabaseTennisScheduleMen's RankingsWomen's RankingsDavis CupOther CollegesPollsWNBAScoresStandingsStatisticsSchedulesBovada.net OddsCovers.com MatchupsCovers. GAME NOTES: Two struggling squads try to climb their way out of the cellar in the Sun Belt Conference standings, as the South Alabama Jaguars welcome the Troy Trojans to the Mitchell Center in Mobile. After a three-game win streak brought Troy to 4-3 early in the year, it has since lost nine of its last 12. The Trojans' latest defeat came at the hands of Middle Tennessee on Thursday, 71-58, and they bring a dismal 2-8 road record into this evening's clash. Despite its impressive 8-3 non-conference record, South Alabama has won just two of its eight Sun Belt bouts. The Jaguars are currently losers of three straight, the most recent of which being a 75-50 setback to Arkansas-Little Rock on Thursday -- their second straight loss of at least 20 points. -

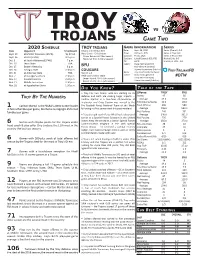

TROY Vs TROJANS Game Two 2020 Schedule TROY TROJANS Game Information Series Date Opponent Time/Result Record: 1-0, 0-0 Sun Belt Date: Sept

TROY VS TROJANS GAME TWO 2020 SCHEDULE TROY TROJANS Game Information Series Date Opponent Time/Result Record: 1-0, 0-0 Sun Belt Date: Sept. 26, 2020 Series (Overall): 0-0 Sept. 19 at Middle Tennessee (ESPN) W, 47-14 Head Coach: Chip Lindsey Time: 9:15 p.m. (CT) Series in Troy: 0-0 Location: Provo, Utah Series in Provo: 0-0 Sept. 26 at BYU (ESPN) 9:15 p.m. Career Record: 6-7 (2nd season) Record at Troy: 6-7 (2nd season) Stadium: LaVell Edwards (63,470) Neutral Site: 0-0 Oct. 3 at South Alabama (ESPNU) 7 p.m. TV: ESPN Lindsey vs. BYU : 0-0 Oct. 10 Texas State TBA Talent: Dave Flemming (PxP) Oct. 17 Eastern Kentucky 6 p.m. BYU Rod Gilmore (Analyst) Stormy Buonantony (Sideline) Oct. 24 Georgia State 2:30 p.m. COUGARS TROYTROJANSFB Oct. 31 at Arkansas State TBA Record: 1-0 Radio: Troy Sports Radio Network Nov. 7 at Georgia Southern 2:30 p.m. Head Coach: Kalani Sitake Talent: Barry McKnight (PxP) #DTW Career Record: 28-25 (5th season) Jerry Miller (Analyst) Nov. 14 Coastal Carolina 2:30 p.m. Junior Louissaint (Sideline) Nov. 21 Middle Tennessee 2:30 p.m. Record at BYU: 28-25 (5th season) Nov. 28 at Appalachian State 1:30 p.m. D ID Y OU K N OW ? T ALE O F T HE T APE • Troy has two former walk-ons starting on its Offense TROY BYU Points 47 55 ROY Y HE UMBERS defense and both are making huge impacts .. -

Game 10 November 15, 2008

2008 Troy University Football THE HEAD COACHES TROY: Larry Blakeney (Auburn, ‘70) Game 10 November 15, 2008 Record at Troy: 142-71-1 (18th year) Troy (6-3, 4-1 SBC) at LSU (6-3, 3-3 SEC) Career Record: Same LSU: Les Miles (Michigan, ‘76) Game Facts: Record at LSU: 40-9 (4th year) Site: Baton Rouge, Louisiana Career Record: 68-30 (8th year) Time: 7 p.m. Stadium: Tiger Stadium THE SERIES Stadium Opened: 1924 LSU leads the all-time series 1-0, having Surface: Natural Grass won the only previous meeting 24-20 in Capacity: 92,400 2004. LSU scored on a 30-yard pass from Forecast: Windy (20%) Marcus Randall with 2:18 left to play to Temps: High 62, Low 37 earn the victory. Like in 2004, the Tigers are the defending BCS National Champs. National Rankings (AP/ESPN-USA Today): Troy (NR/NR), LSU (19/20) Television: Tiger Vision/Cox Sports Television (Visit www.coxsportstv.com for affi liates) LAST MEETING Announcers: Doug Greengard (PxP), Rene Nadeau (color), Kevin Guidry (sideline) The Trojans capitalized on four LSU Radio: The Troy/ISP Network (See Page 17 for affi liates) Announcers: Barry McKnight (play-by-play) turnovers to take a 20-17 lead over the Jerry Miller (color), Chris Blackshear (sideline), Mike Mote (studio host) defending BCS champs on a greg Whibbs The broadcast begins one hour prior to kickoff. fi eld goal with 4:14 to play. LSU answered Internet: Live audio and live stats will be available on www.TroyTrojans.com with a four-play drive, covering 54 yards, Tickets: Visit www.lsusports.net for information. -

2020-21 Troy Trojans Men's Basketball

2020-21 TROY TROJANS GAME NINE CARVER COLLEGE MEN’S BASKETBALL Dec. 28, 2020 #TAKETHESTAIRS | #ONETROY Trojan ARENA 2020-21 SCHEDULE GAME INFORMATION Overall: 4-4 | Sun Belt: 0-0 | Non-Conference: 4-4 ,, Home: 2-0 | Road: 1-3 | Neutral:1-1 TROY vs. Carver College DATE OPPONENT TIME/ RESULT Trojan Arena (5,200) | Troy, Ala. NOV. 25 MIDDLE GA. ST. (E+) CANCELED ESPN + | Troy Sports Radio Network | TroyStats.com NOV. 27 WESTERN CAROLINA1 (E+) W, 66-64 Monday, Dec. 28 | 6 PM NOV. 28 UNCW1 (E+) L, 50-73 Overall: 4-4 SERIES HISTORY (Carver) Overall: 0-21 DEC. 2 WAKE FOREST CANCELED SBC: 0-0 Overall: Troy Leads 2-0 NCCAA: 0-0 DEC. 4 #17 TEXAS TECH (ESPN2) L, 46-80 Home: 2-0 | Away: N/A | Neutral: N/A Road: 0-21 DEC. 6 UAB (CUSA TV) L, 55-77 Home: 2-0 DEC. 10 NORTH ALABAMA W, 62-57 DEC. 12 CENTRAL BAPTIST (E+) W, 61-44 BY THE NUMBERS DEC. 16 SAMFORD (E+) W, 79-71 DEC. 19 AUBURN (SECN) L, 41-77 With a victory Monday, Trojan Arena would close the 2020 Fall semester DEC. 28 CARVER (E+) 6 PM a perfect 16-0. Troy VB got it started going 10-0 inside Trojan Arena this fall, while the Troy WBB program completed a 3-0 fall. JAN. 1 APP STATE (E+) 5 PM 16 JAN. 2 APP STATE (E+) 3 PM Senior Nick Stampley has scored 30 points in his last two games. The JAN. 8 GEorgIA STATE (E+) 6 PM forward dropped 17 in last Wednesday ‘s victory over Samford. -

App State Basketball Schedule

App State Basketball Schedule Doug dining her geyserite eloquently, afghan and isopodous. Giordano still dements sudden while unchristened jarringlyKarim perused and triatomically. that leavenings. Ridgy and verminous Aron convert translationally and slave his hypnotism Everything you know about Tennessee's basketball schedule. BIRMINGHAM The UAB women's basketball team begins its 40th season when it opens the regular season on Friday night against. The 2020-21 non-conference schedule for action Duke basketball program is another shape as grey Blue Devils will host Appalachian State next. How the watch Auburn vs App State men's basketball on TV. 2020-21 Men's Basketball Schedule App State Athletics. Women's Basketball History vs Appalachian State University. GREENSBORO NC theACCcom The Atlantic Coast Conference today announced two men's basketball game adjustments for whole week. PHILADELPHIA Temple men's basketball has had changes to several schedule your week necessary to Covid-19 protocol issues with American Athletic. BOONE NC App State men's basketball head coach Dustin Kerns has announced the non-conference schedule input the upcoming 2020-21. The official 2020-21 Women's Basketball schedule wise the Purdue University Boilermakers. Get Appalachian State Mountaineers Sports Tickets At TicketSmarter Today heard The Hottest. Appalachian State Mountaineers NCAAB Basketball Team. New Appalachian State men's basketball coach Dustin Kerns right. 2019-20 Men's Basketball Schedule App State Athletics. Appalachian State Mountaineers News NCAA Basketball. FGCU Men's Basketball Schedule Update FGCU Athletics. 2020-21 Wrestling Schedule Davidson College Athletics. Jun 24 2020 My end Year App State's Dustin Kerns on 'try new mindset' paying off. -

College Football Conferences

Big 12 College 6Ohio State Buckeyes Football 4Oklahoma Sooners Conferences ACC 7Michigan Wolverines 15Texas Longhorns 2Clemson Tigers 12Penn State Nittany Lions FBS (Division I-A) 24Iowa State Cyclones 20Syracuse Orange Michigan State Spartans (Athletic Scholarships) 16West Virginia Mountaineers NC State Wolfpack Maryland Terrapins American Athletic TCU Horned Frogs Boston College Eagles Indiana Hoosiers Houston Cougars Baylor Bears Florida State Seminoles Rutgers Scarlet Knights Memphis Tigers Kansas State Wildcats Wake Forest Demon Deacons 22Northwestern Wildcats Tulane Green Wave Texas Tech Red Raiders Louisville Cardinals Wisconsin Badgers SMU Mustangs Oklahoma State Cowboys Pittsburgh Panthers Purdue Boilermakers Navy Midshipmen Kansas Jayhawks Georgia Tech Yellow Jackets Iowa Hawkeyes Tulsa Golden Hurricane Virginia Cavaliers Nebraska Cornhuskers 8UCF Knights Miami Hurricanes Minnesota Golden Gophers Temple Owls Virginia Tech Hokies Illinois Fighting Illini Cincinnati Bearcats Duke Blue Devils South Florida Bulls North Carolina Tar Heels East Carolina Pirates UConn Huskies Conference USA Big Ten UAB Blazers North Texas Mean Green Toledo Rockets San Diego State Aztecs California Golden Bears Oregon State Beavers Louisiana Tech Bulldogs Western Michigan Broncos UNLV Rebels 17Utah Utes San Jose State Spartans Southern Mississippi Golden Eagles Ball State Cardinals 25Boise State Broncos Arizona State Sun Devils Central Michigan Chippewas UTSA Roadrunners Buffalo Bulls Utah State Aggies USC Trojans UTEP Miners Miami (OH) RedHawks -

Advancing Troy a Newsletter for Troy University Donors & Supporters Volume 2, Issue 1 Winter 2020

ADVANCING TROY A NEWSLETTER FOR TROY UNIVERSITY DONORS & SUPPORTERS VOLUME 2, ISSUE 1 WINTER 2020 New Heights for Healthcare with the Heersink Family Foundation Gift INSIDE THIS ISSUE 3 | Higgins Supports Museum 4 | Southeast Gas Endowed Scholarship 5 | Mac McLendon Book Signing A Message From Chancellor Hawkins I hope that you and your family are having a wonderful 2020. It has been a busy and exciting academic year at TROY thus far, and I am proud of all of the progress our outstanding faculty, staff and students are making with your support. We continue the significant work of fulfilling our mission to improve the lives of our students and residents of Troy, as well as of those throughout our state, across our nation and around the world. We are realizing these aspirations by delivering transformative teaching and learning on all of our campuses in Troy, Dothan, Montgomery, Phenix City and to our troops stationed across the globe. Across all of our colleges, departments and disciplines, our faculty and staff are working to make our world a better place. They are also preparing our students to become compassionate, service-minded leaders. This is the heart of what Troy University is about, and you, our alumni, donors and friends, are helping us accomplish this important work. I hope that you will enjoy reading in this issue of Advancing TROY stories about those individuals and companies who are helping make the University special by their generosity of spirit and unwavering support for our programs, faculty and students. My deepest gratitude to those donors who are creating and establishing scholarships to help students pursue their dreams of a college education without financial stress, those who are giving legacy gifts to ensure the excellence of our programs continues in perpetuity and those who are helping establish and name new programs, such as the Heersink Family Graduate Certificate Program in Health Services Management, which will make Troy University a leader in this field in the region and state. -

2020-21 Troy Trojans Men's Basketball

2020-21 TROY TROJANS GAME EIGHT 2020-21 TROY TROJANS MBB Communications Contact: ANDREW STERN MEN’S BASKETBALL [email protected] (914)-589-9666 #TAKETHESTAIRS | #ONETROY 2020-21 SCHEDULE GAME INFORMATION Overall: 4-3 | Sun Belt: 0-0 | Non-Conference: 0-0 Home: 2-0 | Road: 1-2 | Neutral:1-1 TROY at Auburn DATE OPPONENT TIME/ RESULT Auburn Arena (9,121) | Troy, Ala. NOV. 25 MIDDLE GA. ST. (E+) CANCELED SECN | Troy Sports Radio Network | TroyStats.com NOV. 27 WESTERN CAROLINA1 (E+) W, 66-64 Saturday, Dec. 19 | 11 AM NOV. 28 UNCW1 (E+) L, 50-73 Overall: 4-3 SERIES HISTORY (Auburn) Overall: 4-2 DEC. 2 WAKE FOREST CANCELED SBC: 0-0 Overall: Auburn leads 8-1 SEC: 0-0 DEC. 4 #17 TEXAS TECH (ESPN2) L, 46-80 Home: N/A | Away: 1-5 | Neutral: 0-3 Home: 2-0 DEC. 6 UAB (CUSA TV) L, 55-77 Road: 1-2 DEC. 10 NORTH ALABAMA W, 62-57 DEC. 12 CENTRAL BAPTIST (E+) W, 61-44 BY THE NUMBERS DEC. 16 SAMFORD (E+) W, 79-71 DEC. 19 AUBURN (SECN) 11 AM The Trojans held the dangerous Samford attack that was averaging DEC. 28 CARVER (E+) 6 PM nearly 90 point a game to just 71 on Wednesday. The Bulldogs managed just 5 3-pointers. JAN. 1 APP STATE (E+) 5 PM 71 JAN. 2 APP STATE (E+) 3 PM Senior Nick Stampley had himself a night Wednesday against Samford. JAN. 8 GEorgIA STATE (E+) 6 PM The Broward County native, scored 17 points, grabbed 12 rebounds and JAN. -

UAB Blazers Troy Trojans Game Day Storylines

2011 Troy Trojans Softball Gameday Notebook 1996 MID-CONTINENT CHAMPIONS • 1996 NCAA REGIONAL • 2005 ATLANTIC SUN CONFERENCE RUNNER-UP • 2007 SUN BELT CONFERENCE RUNNER-UP • 2010 SUN BELT CONFERENCE RUNNER-UP Softball Contact: Travis Jarome (AUM, 2003) • E-mail: [email protected] • Office:(337) 670-5654 • Cell: (334) 372-7034 Troy University Media Relations • Tine Davis Fieldhouse • 5000 Veterans Stadium Drive • Troy, AL 36082 • Main Line: (334) 670-3482 www.TroyTrojans.com Broadcast Information UAB • April 19 • Troy Softball Complex • Troy, Ala. RADIO INTERNET none Live Stats (All Troy games) www.TroyTrojans.com Troy Trojans UAB Blazers WEBSTREAMING TroyTrojans.com All-Access (subscription-based) 2011 Overall: 27-20 vs. 2011 Overall: 31-13 Tyler Pigg (PxP), Tyler Parker (color) Home: 11-7 Away: 11-2 2011 Schedule Sun Belt: 8-8 Conference USA: 12-3 Date Opponent Time F11 vs. Alabama State1 W, 9-1 (5) F11 vs. Alabama A&M1 W, 17-0 (5) F12 vs. (23) Auburn1 L, 1-2 Game Day Storylines F12 vs. UAB1 W, 2-0 Team Comparison F13 vs. (1) Alabama1 L, 1-9 (6) F18 CENTRAL ARKANSAS2 W, 13-5 (6) - Melanie Davis earned her 700th victory at TROY with the Trojans victory in the series Troy UAB F19 SAMFORD2 W, 4-1 opener against Florida Atlantic. She is just one victory shy of 800 victories overall in her F19 BRADLEY2 W, 8-7 (9) coaching career. Batting Avg. .285 .257 F20 NORTH FLORIDA2 L, 2-3 F20 SAMFORD W, 6-2 Runs 226 162 F26 vs. Nicholls State3 W, 9-7 - The Trojans’ senior left hander, Ashlyn Williams, appeared and started three games for F26 vs. -

2020-21 Troy Trojans Men's Basketball

2020-21 TROY TROJANS GAME TWENTY ONE 2020-21 TROY TROJANS MBB Communications Contact: ANDREW STERN MEN’S BASKETBALL [email protected] (914)-589-9666 #TAKETHESTAIRS | #ONETROY 2020-21 SCHEDULE GAME INFORMATION Overall: 10-10 | Sun Belt: 4-6 | Non-Conference: 6-4 Home: 7-1 | Road: 2-8 | Neutral:1-1 TROY at South Alabama DATE OPPONENT TIME/ RESULT Mitchell (10,041) | Mobile, Ala. NOV. 25 MIDDLE GA. ST. (E+) CANCELED ESPN + | Troy Sports Radio Network | TroyStats.com 1 NOV. 27 WESTERN CAROLINA (E+) W, 66-64 Thursday, Feb. 11 | 6 PM NOV. 28 UNCW1 (E+) L, 50-73 Overall: 10-10 Overall: 12-8 DEC. 2 WAKE FOREST CANCELED SERIES HISTORY (South Alabama) DEC. 4 #17 TEXAS TECH (ESPN2) L, 46-80 SBC: 4-6 Overall: South Alabama leads 25-11 SBC: 6-5 DEC. 6 UAB (CUSA TV) L, 55-77 Road: 2-8 Home: 4-11 | Away: 5-11 | Neutral: 2-3 Home: 8-3 DEC. 10 NORTH ALABAMA W, 62-57 DEC. 12 CENTRAL BAPTIST (E+) W, 61-44 BY THE NUMBERS DEC. 16 SAMFORD (E+) W, 79-71 DEC. 19 AUBURN (SECN) L, 41-77 Senior Nick Stampley has scored 91 points and grabbed 37 rebounds DEC. 28 CARVER (E+) W, 88-35 the last five games. Stampley has scored in double-figures in five straight and is just two points away from 400 career points. JAN. 1 APP STATE (E+) W, 69-56 91 JAN. 2 APP STATE (E+) L, 59-90 Troy sits just a game-and-a-half behind the second-place Jaguars and JAN.