Reframing the 'Left Behind' Race and Class in Post-Brexit Oldham

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

M a R T I N Woolley Landscape Architects

OLDHAM MILLS STRATEGY LANDSCAPE OVERVIEW February 2020 MARTIN WOOLLEY LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS DOCUMENT CONTROL TITLE: LANDSCAPE OVERVIEW PROJECT: OLDHAM MILLS STRATEGY JOB NO: L2.470 CLIENT: ELG PLANNING for OLDHAM MBC Copyright of Martin Woolley Landscape Architects. All Rights Reserved Status Date Notes Revision Approved DRAFT 2.3.20 Draft issue 1 MW DRAFT 24.3.20 Draft issue 2 MW DRAFT 17.4.20 Draft issue 3 MW DRAFT 28.7.20 Draft issue 4 MW CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Scope 3 Methodology 3 BACKGROUND Background History 6 Historical Map 1907 7 LANDSCAPE BASELINE Topography & Watercourses 11 Bedrock Geology 12 National Character Areas 13 Local Landscape Character 14 GMC Landscape Sensitivity 15 Conservation Areas 16 Greenbelt 17 Listed, Converted, or Demolished Mills (or consented) 18 ASSESSMENT Assessment of Landscape Value 20 Remaining Mills Assessed for Landscape Value 21 Viewpoint Location Plan 22 Viewpoints 1 to 21 23 High Landscape Value Mills 44 Medium Landscape Value Mills 45 Low Landscape Value Mills 46 CONCLUSIONS & RECOMMENDATIONS Conclusions 48 Recommendations 48 Recommended Mill Clusters 50 APPENDIX Landscape Assessment Matrix 52 1 SCOPE 1.0 SCOPE 1.1 Martin Woolley Landscape Architects were appointed in November 2019 to undertake 2.4 A photographic record of the key views of each mill assisted the assessment stage and a Landscape Overview to accompany a Mill Strategy commissioned by Oldham provided panoramic base photographs for enabling visualisation of the landscape if a Metropolitan Borough Council. particular mill were to be removed. 1.2 The Landscape Overview is provided as a separate report providing an overall analysis 2.5 To further assist the assessment process, a range of ‘reverse montage’ photographs were of the contribution existing mills make to the landscape character of Oldham District. -

Community Guide

ROCHESTERNH.ORG GREATER ROCHESTER CHAMBER OF COMMERCE 2016 • 1 It’s about People. 7HFKQRORJ\ 7UXVW frisbiehospital.com People are the foundation of what health that promotes faster healing, better health, care is about. People like you who are and higher quality of life. looking for the best care possible—and It’s this approach that has allowed us to people like the professionals at Frisbie develop trust with our patients, and to Memorial Hospital who are dedicated to become top-rated nationally for our quality providing it. of care and services. :HXVHWKHODWHVWWHFKQRORJ\WRKHOSÀQG VROXWLRQVWKDWEHQHÀWSDWLHQWV7HFKQRORJ\ 11 Whitehall Road, Rochester, NH 03867 | Phone (603) 332-5211 2 • 2016 GREATER ROCHESTER CHAMBER OF COMMERCE ROCHESTERNH.ORG contents Editor: 4 A Message from the Chamber Greater Rochester Chamber of Commerce 5 City of Rochester Welcome 6 New Hampshire Economic Development Photography Compliments of: 7 New Hampshire & Rochester Facts Cornerstone VNA Frisbie Memorial Hospital 8 Rochester – Ideal Destination, Convenient Location Great Bay Community College 10 Rochester History Greater Rochester Chamber of Commerce Revolution Taproom & Grill 11 Arts, Culture & Entertainment Rochester Economic Development 13 Rochester Business & Industry Rochester Fire Department A Growing & Diverse Economy Rochester Historical Society Rochester Main Street 14 Rochester Growth & Development Rochester Opera House Business & Industrial Parks Rochester Police Department 15 Rochester Commercial Districts Produced by: 16 Helpful Information Rochester -

Jewson Civils

Page 1 JEWSON CIVILS Coldhurst Street, Oldham, OL1 2PX Trade Counter Investment Opportunity Page 2 Trade Counter Investment Opportunity Jewson Civils, Coldhurst Street, Oldham, OL1 2PX INVESTMENT SUMMARY Opportunity to acquire a single let trade counter unit with secure open storage and loading yard. The accommodation totals 43,173 sq ft (4,011 sq m) and benefits from 40 customer parking spaces; Site area of 3.12 acres (1.27 ha) with a low site coverage of 33%; Let to Jewson Ltd (guaranteed by Saint-Gobain Building Distribution Limited) for a term of 15 years from 3 July 2007 (expiring 2 July 2022), providing 2.75 years term certain; A low current passing rent of £213,324 per annum, reflecting only £4.94 per sq ft. Saint-Gobain Building Distribution Limited has a D&B rating of 5A2, representing a minimum risk of business failure; Long Leasehold (808 years unexpired); Offers are sought in excess of £2,855,000 (Two Million, Eight Hundred and Fifty Five Thousand Pounds), subject to contract and exclusive of VAT. A purchase at this level reflects an attractive net initial yield of 7.00% and a capital value of £66 per sq ft (assuming purchaser’s costs of 6.43%). Page 3 Trade Counter Investment Opportunity Jewson Civils, Coldhurst Street, Oldham, OL1 2PX LOCATION Oldham is a town within the Metropolitan Borough of Oldham, one of the ten boroughs that comprise Greater Manchester conurbation and a major administrative and commercial centre. The town lies approximately 8 miles north east of Manchester City Centre via the A62 (Oldham Road), 4 miles north of Ashton-under-Lyne via A627 (Ashton Road) and 6 miles south of Rochdale via the A671 (Oldham Road). -

Oldham District Budget Report

Report to Oldham District Executive Oldham District Budget Report Portfolio Holder: Cllr B Brownridge, Cabinet Member for Cooperatives & Neighbourhoods Officer Contact: Helen Lockwood, Executive Director, Cooperatives & Neighbourhoods Report Author: Simon Shuttleworth; District Coordinator, Oldham Ext. 4720 27th January 2016 Reason for report To advise the Oldham District Executive of the current budget position and seek approval for proposed items of spend. Recommendations 1. To note the current budget position 2. To make the following budget allocations (revenue, unless stated otherwise): a) Winterbottom Street Bollards £2,700 Capital b) Millennium Green/Sholver Centre £3,000 Capital c) Works to Stoneleigh Park £2,500 Capital d) Crèche for Mindfulness Course £720 e) Football provision at Broadfield School pitch £2,658 f) Waste and litter project £7,126 g) Highways Improvements £20,000 Capital h) Alleygating – Glodwick £2,000 Capital i) Clarksfield Alleyway Initiative £4,300 j) Arundel Street Park £2,000 Capital k) Stoneleigh Park Cabin pool table - £291 Revenue Oldham District Executive 27th January 2016 Oldham District Budget Report 1 Background 1.1 The Oldham District Executive has been assigned the below budget for 2015/2016: Revenue 2015/2016 Capital 2015/2016 Alexandra £10,000 £10,000 Coldhurst £10,000 £10,000 Medlock Vale £10,000 £10,000 St James’ £10,000 £10,000 St Mary’s £10,000 £10,000 Waterhead £10,000 £10,000 Werneth £10,000 £10,000 1.2 Each Councillor also has an individual budget of £5000 for 2015/2016 Allocations to date are shown in the attached Appendix 1 2 Current Position 2.1 Revenue and Capital Budgets Allocations made so far are shown below. -

Millyard District Millyard District

Millyard District Millyard District Abstract In the decades following the closure of the mills, Nashua continued to grow and prosper, but in a The Millyard District has always been home to primarily suburban spatial pattern. The more tra- local manufacturing and industrial businesses. ditional urban fabric of the downtown and Millyard Since 1823, the district housed small and me- saw periods of disinvestment and stagnation as dium sized industrial uses. After the collapse of the suburbs simultaneously expanded. the traditional mill businesses in the 1940’s, these buildings saw new uses - residential, artist spac- Recently, the City of Nashua and the State com- es, churches, and light manufacturing. These pleted a road project through the Millyard called buildings have kept their traditional charm and the Broad Street Parkway. The project created a property owners have allowed the interior spac- second north south connection over the Nashua es to be transformed for tenant needs. With low river and opened up the formerly closed off mill vacancy and low business turnover in the area, district to the broader community. The project did it is clear that there is demand to be located in come at a significant financial cost and required the Millyard District. Connectivity within the dis- the demolition of several historic mill buildings. trict and to Nashua’s downtown is major problem While local reviews of the project are generally facing the Millyard District. positive, the road has disrupted the pedestrian environment in the Millyard, creating western and Through improved pedestrian connections in the eastern portions due to a lack of proper pedestri- district, businesses and residential units would be an road crossing facilities. -

Urban Panel Review Paper Rochdale June 2018

URBAN PANEL REVIEW PAPER Rochdale Contents 1. Introduction 2. Initial thoughts 3. The southern part of the Heritage Action Zone 4. The town centre and northern part of the Heritage Action Zone 5. Other matters 6. Conclusions and Recommendations 1 Introduction 1.1 Since the beginning of the nineteenth century, Drake Street, the Regency thoroughfare which connected the centre of one of Lancashire’s most successful textile towns with its railway station, was Rochdale’s principal shopping street. It was a street which, for almost 150 years, was the bustling commercial heart of the town with department stores, two Co-operatives (including the Rochdale Pioneers’ first bespoke shop), impressive public halls and numerous small shops and businesses. 1.2 By the end of the twentieth Century, however, all this had changed. The structural changes in the retail economy, nationally, combined with the northerly shift of the main retail focus of the town due to the opening of not one, but two, large shopping centres had a catastrophic impact upon the vitality and viability of this historic thoroughfare. Today, several of what were Drake Street’s most iconic buildings have gone or have been irreparably altered, many other properties lie vacant or, at best, in marginal uses, and a large proportion are in a parlous state of repair. The once bustling street full of people that was shown in photographs of Drake Street from the 1960s is now largely devoid of activity. 1.3 Whilst Rochdale town centre, itself, also witnessed a similar downturn in its economic fortunes during the same period, the decline was nowhere near as marked nor the impacts upon its buildings and townscape quite so severe. -

Lowell National Historical Park Foundation Document (Overview Version

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Foundation Document Overview Lowell National Historical Park Massachusetts © James Higgins Contact Information For more information about the Lowell National Historical Park Foundation Document, contact: [email protected] or (978) 970-5000 or write to: Superintendent, Lowell National Historical Park, 67 Kirk Street, Lowell, MA 01852 Description © James Higgins Growth and change have long dominated the American As crowded tenements took the place of Lowell’s well system of values. Industry flourished in 19th-century regulated system of boarding houses, Lowell became an America as major technological advancements in industrial city similar to others in New England. transportation, power production, and industrial manufacturing facilitated a fundamental shift from rural Competition within the textile industry increased continually farm-based communities to a modern urban-industrial throughout the 19th century. Eventually, the combination of society. Lowell, Massachusetts, 30 miles northwest a cheaper, less unionized workforce; newer, more efficient of Boston, was founded in 1822 as a seminal planned factories and machinery; cheaper real estate; and lower industrial city and became one of the most significant taxes persuaded the textile industry to move south. Eight of textile producing centers in the country. The city of Lowell Lowell’s original 10 textile firms closed their doors for good is not, as is sometimes claimed, the birthplace of the during the 1920s, and the remaining two closed in the 1950s. Industrial Revolution in America. Most of the developments The city fell into a long depression that lasted through the associated with this phenomenon in the nation’s history 1960s. -

Greater Manchester… Significantly Lower Than the National Average (73.9%)

Where to now for widening access? 2020 and beyond A brief story of University Campus Oldham... History, location, context, challenges, opportunities. Parallels with the students’ journeys Oldham Oldham’s History At its peak, the most productive cotton spinning mill town in the world producing more cotton than France and Germany combined. Oldham’s People Total population (000s):218.8 % White, British: 80.484 % White Irish: 0.823 % White, other: 1.463 % Mixed: 1.6 % Asian or Asian British: 13.574 % Black or Black British: 1.234 % Chinese: 0.32 % Other: 0.411 SOURCE: ONS Employment Oldham (64.8%) currently has the 8th highest employment rate within Greater Manchester… significantly lower than the national average (73.9%). The employment rate in Oldham over the last 5 years has shown no measureable improvement whereas across England the employment rate has increased by 3.9 percentage points. Source: Annual Population Survey 2015 Wages Oldham has traditionally had low wage levels in terms of residents and work place earning potential. In 2011, Oldham had both the lowest residential (£412 per week) and workplace (£399 per week) median weekly wage levels in Greater Manchester. By 2015 wages for both residents (£444 a week) and those working in Oldham (£428 a week) remain significantly below the England averages (£533 and £532 a week respectively). Qualifications Even though progress has been made in recent years, Oldham still has a significantly higher percentage of its working age population with no qualifications (15.0%), compared to the GM (10.1%) and national (8.4%) averages. Young people are gaining higher levels of qualifications, it will take many decades for Oldham to narrow the gap to national rates. -

New Hampshire

DOVER NEW HAMPSHIRE City of Opportunity A Message from Dover Economic reetings, Development and City Planning G & Community Development On behalf of the city of Dover, NH, I thank you for considering our great community. Dover was established in 1623 and has a rich history of industry, education and Dover, New Hampshire: Unique, Cooperative, culture which rivals any community in the State or region. Proactive. That’s how we see our city. Dover has worked hard to build a business-friendly, proactive government Dover is a great place to live, work and play. From our his- infrastructure, where departments cooperate to assist toric downtown to our rich cultural events, Dover is a place existing businesses, and relocating companies, so that where people want to settle down and raise their families. both fulfill their potential. Great schools, family friendly events and close proximity One example of this cooperation, is the close to the State University hub add to the appeal of Dover. working relationship between the Dover Business & Industrial Development Authority and the City of Dover Our proximity to major highways, deep water ports, and Planning and Community Development Department. regional airports adds to the draw of an already vibrant Both entities work together with our clients from start to community. Dover is within a one hour drive of major finish. This integration ensures that permitting, engineer- cities, the Atlantic Ocean, the White Mountains and a ing, plan acceptance, variance consideration, and zoning number of prime hiking and ski resorts. approvals happen in a transparent and expeditious man- ner. There is a keen awareness that common sense and Dover offers an educated workforce, a technologically flexibility within the rules are needed to make projects advanced infrastructure and a proactive Planning Board work. -

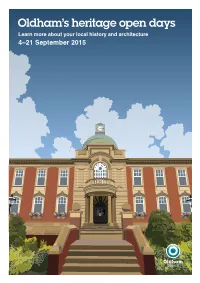

Oldham's Heritage Open Days

Oldham’s heritage open days Learn more about your local history and architecture 4–21 September 2015 12pp Heritage OD leaflet 2015 .indd 1 04/08/2015 14:53 Welcome to Oldham Council’s Heritage Open Days, your opportunity to find out more about the history and heritage of your area. From talks to walks there’s plenty to discover, whether you’re interested in architecture or heritage or just curious about the history around you. 6-21 September Every Monday and Wednesday A Tale of the Dardanelles Family History Advice A display telling the story of the 2pm-4pm: Needing help with family Oldham Territorials at Gallipoli. history? Expert advice available. Oldham Local Studies and Archives, Oldham Local Studies and Archives, 84 Union Street, Oldham OL1 1DN. 84 Union Street, Oldham OL1 1DN. Mon and Thurs 10am-7pm; Tues Disabled access; toilets 10am-2pm; Wed and Fri 10am-5pm; Sat 10am-4pm. 4-6 September Disabled access; toilets Flower festival 12noon-5pm: Holy Trinity Church, Oldham Town Centre Shaw. Commemorating the 500th Past and Present anniversary of the site being a place Photographs comparing Oldham of worship. Church Road, Shaw, Town Centre of today with that of the Oldham, OL2 7SL. Disabled access; past. Oldham Town Centre Office, toilets; parking; refreshments 12 Albion Street, Oldham, OL1 3BG. Mon-Fri 10am-5pm. Disabled access Saturday 5 September Growing Up in Old St Mary’s Holy Trinity Church, Bardsley Display of photographs, books 9am-12noon: Find out more about and memories of the making of the the church and its community; documentary ‘Just Like Coronation includes tours of clock tower. -

Official Directory. (Slater's

1982 OFFICIAL DIRECTORY. (SLATER'S Bury' Co-operative Manufacturing Cb. Ltd. Haugh Cotton Spinning & Manufacturing Co Park Road Spinning Co. Ltd. Dukinfteld Wellington mills, Elton, Bury Ltd. Newhey, near Rochdale Parkside Spinning Uo. Ltd. Royton Bury Cotton Spinning and Manufacturing Co. Ha.worth Richard & Oo. Ltd. Egerton, Tatton Patrrson F. G. & Co. 13 St. Ann l't Ltd. Barnbrook mills, Bury Ordsal 1.< Tbrostle Nest mtlls, Ordsal, Salforcl Pearl Mill Co. Ltd. Glodwick, Oldham Busk Mills Co. Ltd. Busk mills; Blli!k, Oldham Heginbottom B. & Sons, Ltd. Junction milLs, Peel Ro:5er & Jame& Henry, Frceto>vn and Butterworth Alfred, Glebe mills, Holllnwood Ashton-unrler-Lyne Hope mills, Bury ButlA'rworth Edwin & Co. Pollard st Hey Spinning Oo. Ltd. Sun Hill mill, Hey, Peel Spinning and Manufacturing Co. Ltd. Byrom J. R. (Joseph Byrom & Sons), Royal, Lee~, near Oldham Chamber hall, Bury A.l bion and Victoria. mills, Droylsden Hirst R.& Sons. Firth Street mills, Huddera field Peers Robert, Brookllmouth mill, Elton, Bury Bythell J. K. Sedgley park, Prestwich Hobson T. A. S. 26 Corpoi"!ltion st Phillips Frederick, 96 Deansgate Campbell H. E ..Manche3ler Hollinwood Spinning Co. Ltd. Hollinwood, Pick up J ames & Brother, Ltd. Spring and Isle Canal Mills Co. (Ciayton-le-Moors), Ltd. Clay- near Oldham of Man mills, Newcb.urch ton-le-Moors Holly Mill Co. Ltd. Royton Pine Mill Co. Ltd. North Moor, Oldham Carver Brothers & Co. Ltd. 30 St. Ann st Honeywell Cotton Spinning Oo. Ltd. Ashton Platt Bros. & Co. LW. Oldllam Castle Spinning Co. Ltd. Quay st. Stalybridge rd. Oldham Platt Ed. Ld. Clough mill~, Hayfield) near Central Mill Co. -

402 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

402 bus time schedule & line map 402 Oldham - Royal Oldham Hospital - Royton Circular View In Website Mode The 402 bus line (Oldham - Royal Oldham Hospital - Royton Circular) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Derker: 7:50 AM - 4:05 PM (2) Oldham: 7:32 AM - 5:20 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 402 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 402 bus arriving. Direction: Derker 402 bus Time Schedule 115 stops Derker Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:50 AM - 4:05 PM Thackeray Road, Derker Whetstone Hill Lane, Manchester Tuesday 7:50 AM - 4:05 PM Wordsworth Road, Derker Wednesday 7:50 AM - 4:05 PM Vulcan Street, Derker Thursday 7:50 AM - 4:05 PM Friday 7:50 AM - 4:05 PM Abbotsford Road, Derker Abbotsford Road, Manchester Saturday 8:30 AM - 3:30 PM Stoneleigh Street, Derker Sydenham Street, Derker Sydenham Street, Manchester 402 bus Info Direction: Derker London Road, Derker Stops: 115 Roseberry Avenue, Manchester Trip Duration: 114 min Line Summary: Thackeray Road, Derker, Yates Street, Derker Wordsworth Road, Derker, Vulcan Street, Derker, Abbotsford Road, Derker, Stoneleigh Street, Derker, Bartlemore Street, Derker Sydenham Street, Derker, London Road, Derker, Yates Alexandra Crescent, Manchester Street, Derker, Bartlemore Street, Derker, Acton Street, Derker, Derker Metrolink Stop, Derker, Yates Acton Street, Derker Street, Derker, Derker Metrolink Stop, Derker, Acton Street, Manchester Kirsktone Close, Oldham Edge, Edge Lane Road, Oldham Edge, Charter Street,