The Sir Robert Menzies Oration on Higher Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History Record

AUSTRALIAN VETERINARY HISTORY RECORD I b Number 28 I fi: The Australian Veterinary History Record is published by the Australian Veterinary History Society in the months of March, July and November. Editor: Dr P.J. Mylrea, 13 Sunset Avenue, Carnden NSW 2570. Officer bearers of the Society. President: Dr M. Baker Librarian: Dr R. Roe Editor: Dr P.J. Mylrea Committee Members: Dr Patricia. McWhirter Dr Paul Canfield Dr Trevor Faragher Dr John Fisher AUSTRALIAN VETERINARY HISTORY RECORD JuIy 2000 Number 28 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING - Melbourne - 2003 The next meeting of the Society will be held in Melbourne in 2001 as part of the AVA Conference with Dr Trevor Faragher as the Local Organism. This is the first caIl for papers md those interested should contact Trevor (28 Parlington Street, Canterbury Vic 3 126, phone (03) 9882 64 12, E-mail [email protected]. ANNUAL MEETING - Sydney 2000 The Annual Meeting of the Australian Veterinaq History Society for 2000 was held at the Veterinary School, University of Sydney on Saturday 6 May. There was a presentation of four papers on veterinary history during the afternoon. These were followed by the Annual General Meeting details of which are given below. In the evening a very pleasant dher was held in the Vice Chancellor's dining room. MINUTES OF THE 9TH ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AUSTRALIAN VETERINARY HISTORY SOCIETY: SYDNEY MAY 6 2000 at 5:00 pm PRESENT Bob Taylor; Len Hart; PauI Canfield; Rhonda Canfield; John Fisher; John Bolt; Mary Holt; Keith Baker; Rosalyn Baker; Peter Mylrea; Margaret Mylrea; Doug Johns; Chris Bunn;; John Holder APOLOGES Dick Roe; Bill Pryor; Max Barry; Keith Hughes; Harry Bruhl; Geoff Kenny; Bruce Eastick; Owen Johnston; Kevin Haughey; Bill Gee; Chas SIoan PREVIOUS lbfrwTES Accepted as read on the motion of P Mylred R Taylor BUSINESS ARISING Raised during other business PRESIDENT'S REPORT 1 have very much pleasure in presenting my second presidential report to this annual meeting of the Australian Veterinary Historical Society. -

SALE! SALE! SALE! More Issue of Sem^ Per Floreat This Text Books, General Books, Children's Books

• 0 <^ n —<>^>»»^*»—fr«»<mm<>. M)^»»^VO«to««»O^MM Once custom constrained us to ration Our talk on tlie topic oi passion But Alfred C. Kinsey Okmn,dTheUftiM€HU(/dQ(Ajee/tt^^ Has sliattered such whimsy Vol, XML No. 10. TUESDAY. SEPTEMBER 22. 1953. And made its discussion the iasldon* Registered at G.P.O., Brisbane, for- i transmission by port as a periodical. DISGUSTING SCENES AT UNION COLLEGE Three Naked Women Forcibly Ejected . , Prominent Student Skipped Town No, it didn't happen; nor unioriunately is ii ever likely lo, but novr Ihat you've been sj'mptoms of life from its readers, it Is your paper, then in years to and driven almost to lighting tjon- come we may have a student paper roped in you nJight as well keep on reading. Who knovrs but that might be a sexy innuendo fires -when some lone soul is moved worthy of the name. If, on the lower down the page? to write a letter to the editor. other hand, you continue to neglect It is about time that the sex-1 already. bestir themselves sufficiently lo put In the not very distant future this and disparage it, leaving it entirely cTazed adolescents who infect tliis The fault is entirely yours. Sem pen to paper and advise ns as to institution will exhaust its stocic of to the editor and his henchmen, University began to realise that per. this year, lias tried desperately where and how it can be im fools idiot enough to talce on the then Semper will surely rot, and Semper Floreat is supposed to be to initiate thought and controversy proved. -

Politics, Power and Protest in the Vietnam War Era

Chapter 6 POLITICS, POWER AND PROTEST IN THE VIETNAM WAR ERA In 1962 the Australian government, led by Sir Robert Menzies, sent a group of 30 military advisers to Vietnam. The decision to become Photograph showing an anti-war rally during the 1960s. involved in a con¯ict in Vietnam began one of Australia's involvement in the Vietnam War led to the largest the most controversial eras in Australia's protest movement we had ever experienced. history. It came at a time when the world was divided between nations that were INQUIRY communist and those that were not; when · How did the Australian government respond to the communism was believed to be a real threat to threat of communism after World War II? capitalist societies such as the United States · Why did Australia become involved in the Vietnam War? and Australia. · How did various groups respond to Australia's The Menzies government put great effort into involvement in the Vietnam War? linking Australia to United States foreign · What was the impact of the war on Australia and/ policy in the Asia-Paci®c region. With the or neighbouring countries? communist revolution in China in 1949, the invasion of South Korea by communist North A student: Korea in 1950, and the con¯ict in Vietnam, 5.1 explains social, political and cultural Australia looked increasingly to the United developments and events and evaluates their States to contain communism in this part of the impact on Australian life world. The war in Vietnam engulfed the 5.2 assesses the impact of international events and relationships on Australia's history Indochinese region and mobilised hundreds of 5.3 explains the changing rights and freedoms of thousands of people in a global protest against Aboriginal peoples and other groups in Australia the horror of war. -

Australian Political Elites and Citizenship Education for `New Australians' 1945-1960

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sydney eScholarship Australian Political Elites and Citizenship Education for `New Australians' 1945-1960 Patricia Anne Bernadette Jenkings Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of Sydney MAY 2001 In memory of Bill Jenkings, my father, who gave me the courage and inspiration to persevere TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF CONTENTS........................................................................... i ABSTRACT................................................................................................................ iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................. vi ABBREVIATIONS..................................................................................................vii LIST OF TABLES ..................................................................................................viii LIST OF FIGURES................................................................................................. ix INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................... 1 Theoretical Orientation ................................................................................... 9 Methodological Framework.......................................................................... 19 CHAPTER ONE-POLITICAL ELITES, POST-WAR IMMIGRATION AND THE QUESTION OF CITIZENSHIP .... 28 Introduction........................................................................................................ -

The Legacy of Robert Menzies in the Liberal Party of Australia

PASSING BY: THE LEGACY OF ROBERT MENZIES IN THE LIBERAL PARTY OF AUSTRALIA A study of John Gorton, Malcolm Fraser and John Howard Sophie Ellen Rose 2012 'A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of BA (Hons) in History, University of Sydney'. 1 Acknowledgements Firstly, I would like to acknowledge the guidance of my supervisor, Dr. James Curran. Your wisdom and insight into the issues I was considering in my thesis was invaluable. Thank you for your advice and support, not only in my honours’ year but also throughout the course of my degree. Your teaching and clear passion for Australian political history has inspired me to pursue a career in politics. Thank you to Nicholas Eckstein, the 2012 history honours coordinator. Your remarkable empathy, understanding and good advice throughout the year was very much appreciated. I would also like to acknowledge the library staff at the National Library of Australia in Canberra, who enthusiastically and tirelessly assisted me in my collection of sources. Thank you for finding so many boxes for me on such short notice. Thank you to the Aspinall Family for welcoming me into your home and supporting me in the final stages of my thesis and to my housemates, Meg MacCallum and Emma Thompson. Thank you to my family and my friends at church. Thank you also to Daniel Ward for your unwavering support and for bearing with me through the challenging times. Finally, thanks be to God for sustaining me through a year in which I faced many difficulties and for providing me with the support that I needed. -

Menzies and Howard on Themselves: Liberal Memoir, Memory and Myth Making

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences & Humanities 1-1-2018 Menzies and Howard on themselves: Liberal memoir, memory and myth making Zachary Gorman University of Wollongong, [email protected] Gregory C. Melleuish University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Law Commons Recommended Citation Gorman, Zachary and Melleuish, Gregory C., "Menzies and Howard on themselves: Liberal memoir, memory and myth making" (2018). Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers. 3442. https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers/3442 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Menzies and Howard on themselves: Liberal memoir, memory and myth making Abstract This article compares the memoirs of Sir Robert Menzies and John Howard, as well as Howard's book on Menzies, examining what these works by the two most successful Liberal prime ministers indicate about the evolution of the Liberal Party's liberalism. Howard's memoirs are far more 'political', candid and ideologically engaged than those of Menzies. Howard acknowledges that politics is about political power and winning it, while Menzies was more concerned with the political leader as statesman. Howard's works can be viewed as a continuation of the 'history wars'. He wishes to create a Liberal tradition to match that of the Labor Party. Disciplines Arts and Humanities | Law Publication Details Gorman, Z. -

Australian Veterinary History Record

AUSTRALIAN VETERINARY HISTORY RECORD I Number 25 The Australian Veterinary History Record is published by the Australian Veterinary History Society in the months of March, July and November. Editor: Dr P.J. Mylrea, 13 Sunset Avenue, Camden NSW 2570. ............I.. ..... Officer bearers of the Society. President: Dr K. Baker Librarian: Dr R. Roe Editor: Dr P.J. Mylrea Committee Members: Dr P. Mc Whirter Dr M. Lindsay Dr R Taylor Dr J. Auty AUSTRALIAN VETERTNARY HISTORY RECORD July 1999 Number 25 AUSTRALIAN VETERINARY HISTORY SOCIETY MEETING 2000 Following the st~ccessful1 999 canference in Canberra in May it was decided to hold the annual conference of the Society for the year 2000 in Sydney. At this stage of planning it is anticipated the venue wiII be the University of Sydney. Saturday ti May 2000 with a dinner in the evening at the recently opened Veterinary Science Conference Centre. Already a number of veterinarians have offered to present papers and the Society is now calling far further speakers to present papers of veterinary historical interest at this meeting. Correspondence should be addressed to the President Dr Keith Baker. 65 Latimer Road, Bellewe Hill, NSW 2023; phone (02) 9327 3853; fax (02) 9327 1458. MINUTES OF THE 8TH ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AUSTRALIAN VETERINARY HISTORY SOCIETY Canberra May 1 1999 at 5:00 pm PRESENT BobTayInr; Leila Taylor; Catherine Evans; Darwin Rennell: Mark Lindsey, Kevin Doyle; Paul Canfield: Rhonda Canfield; Robin Giesecke; Bill Gee: John Fisher; John Auty; Mary Haft; Keith Baker; Rosalyn Baker; Peter Mylrea; Margaret Mylrea; Ray Everett; Ann Everett; Doug Johns; Trevor Doust; Dick Roe: Chris Bunn; Neil Tweddle; Bob Munro: Doug .lolms, Lyall Browne APOLOGIES ' Elugh Gordon; Len Hart; S Sutherland; M Anderson PREVIOUS MINUTES Accepted as read an the motion of P MyLrealR Taylor BUSINESS ARISING Nil PRESIDENT'S REPORT T have very much pleasure in presenting my first presidential report to this annual meeting of the Australian Veterinary Historical Society. -

The Leader of the Opposition

The Leader of the Opposition ‘…just as there can be no good or stable government without a sound majority, so there will be a dictatorial government unless there is the constant criticism of an intelligent, active, and critical opposition.’ –Sir Robert Menzies, 1948 The practice in Australia is for the leader of the party or coalition that can secure a majority in the House of Representatives to be appointed as Prime Minister. The leader of the largest party or Hon. Dr. H.V. Evatt coalition outside the government serves as Leader of the Opposition. Leader of the Opposition 1951 - 1960 The Leader of the Opposition is his or her party’s candidate for Prime National Library of Australia Minister at a general election. Each party has its own internal rules for the election of a party leader. Since 1967, the Leader of the Opposition has appointed a Shadow Ministry which offers policy alternatives and criticism on various portfolios. The Leader of the Opposition is, by convention, always a member of the House of Representatives and sits opposite the Prime Minister in the chamber. The Senate leader of the opposition party is referred to as the Leader of the Opposition in the Senate, even if they lead a majority of Senators. He or she usually has a senior Shadow Ministry role. Australia has an adversarial parliamentary system in which the Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition face off against one another during debates in the House of Representatives. The Opposition’s role is to hold the government accountable to the people and to Parliament, as well as to provide alternative policies in a range of areas. -

Sir John Mcewen, PC, GCMG, CH Prime Minister 19 December 1967 to 10 January 1968

18 Sir John McEWEN, PC, GCMG, CH Prime Minister 19 December 1967 to 10 January 1968 McEwen became the 18th prime minister after serving as leader of the Country Party in the coalition government since 1958. He assumed a caretaker role after the disappearance of Harold Holt. Member of the Country Party of Australia. Member of the House of Representatives 1934-1971. Held seat of Echuca 1934-37, Indi 1937-49 and Murray 1949-71. Joined parliamentary Country Party 1934-1971. Minister of the Interior 1937-39, External Affairs 1940, Air and Civil Aviation in 1940-41, Commerce and Agriculture 1949-56, Trade 1956-63, Trade and Industry 1963-71. McEwen ceased to be prime minister when Liberal Party senator, John Gorton, won a ballot of Liberal parliamentarians on 9 January 1968. Main achievements (1937-1968) Minister in the Cabinets of five heads of government. Member of Australian Advisory War Council 1940-1945. Member of Australia’s delegation to conference to establish United Nations 1945. Held key trade and commerce portfolios for 20 years. Developed influential international networks in business and government. Led numerous trade delegations including negotiation of controversial Australia-Japan trade agreement 1957, six years after peace treaty signed with Japan. Linked Australia’s trade to its capacity to fight Communism during Vietnam War. Personal life Born 29 March 1900 in Chiltern, Victoria. Died 20 November 1980 in Toorak, Melbourne. Raised by grandmother in Wangaratta then Dandenong after the death of mother in 1901 and father in 1907. Educated at Wangaratta state school 1907-1913. Left school at 13 to work at pharmaceutical company. -

Copy of UC Sport Intervarsity Guide

INTERVARSITY GUIDE 2019 #TEAMUC UC SPORT | INTERVARSITY FEB MAR APR MAY O Week UC v. ANU Australian National UC Intervarsity Running Festival Championships 4th - 8th Location UC/ANU Location TBC Trials February 27th - 28th March 13th - 14th April Start May UC v. ANU Nationals Intervarsity Triathlon MAY JUN Trials Mooloolaba Intervarsity Bay Indigenous Start February 17th March Run Nationals UTS, Sydney UWA, Perth National 3rd May 24th - 28th June Championships Trials Nationals Start March Swimming Sydney Olympic Park 10th - 12th May www.ucsport.com.au | 0400 626 199 [email protected] CALENDAR | 2019 JUL AUG SEP OCT Nationals Division UC Sport v. ACU Nationals Nationals 2 Sport Orienteering Division 1 Gold Coast, QLD Canberra, ACT Wagga, NSW Gold Coast, QLD 7th - 11th July 15th August 28th September 29th Sept - 3rd Oct Intervarsity OzTag Nationals Snow Nationals Location TBC Thredbo, NSW Division 1 Date TBC 25th - 29th August Gold Coast, QLD DEC Nationals T20 29th Sep - 3rd Location TBC Oct December www.ucsport.com.au | 0400 626 199 [email protected] NATIONAL UNIVERSITY CHAMPIONSHIPS Division 1 and 2 The National University Championships hosted by UniSport Australia is the premier university sporting event on the intervarsity calendar, with 42 Universities from across Australia competing in over 30 sports to determine who will be crowned the overall winner. UC has had a strong representation at previous Nationals events and are determined to continue that strong run into the future. By joining Team UC, you will have the opportunity to develop your sporting skills all whilst making friends and travelling around Australia. -

Sir Robert Menzies

MENZIES Sir Robert Menzies Personalities - Painting of Sir Robert Menzies by Ivor Hele , 1970 National Archives of Australia A1500, K22849 NEW SOUTH WALES MASONIC CLUB MAGAZINE Club Founded 1893 Print Post Publication PP244187-00007 Issue 38, March 2009 PRESIDENT’S REPORT GENERAL MANAGER’S With our new caterers now on board and fully functional we have seen a significant increase in the use of Cello’s Dear Fellow Members, REPORT restaurant. I would encourage all Members and Guests to make Since I last wrote to report to you, the Vice President, the Hello everyone and welcome to the March a reservation when you wish to dine there so that we do not disappoint anyone. Please call Cello’s direct on 9284 1014 to General Manager and I have once again attended the edition of the Members magazine. We have see how they can assist you. Annual Conference of Clubs NSW as the representatives of experienced a dramatic downturn in business this Club. activity over the last six months and I think that We plan to have an open day / canapés and drinks for Members there is a little more pain to come. That’s the to introduce you all to David Allison and staff. It is our aim to A new feature at this conference was an elective seminar on the subject of club “bad news” the “good news” is that we are in a strong position showcase to all Members the culinary delights for which David amalgamations. It was well attended. The fact that such a seminar was held at to ride out the storm as we proceed through 2009. -

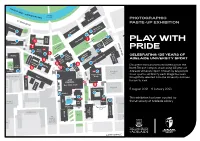

Play with Pride Image List

PHOTOGRAPHIC PASTE-UP EXHIBITION 7 1 PLAY WITH 2 PRIDE 3 CELEBRATING 125 YEARS OF 4 ADELAIDE UNIVERSITY SPORT 6 8 Discover historical photos exhibited across the 5 10 North Terrace Campus, showcasing 125 years of Adelaide University Sport. Chosen by key people in our sports community, each image has been thoughtfully selected from the University Archives for you to view. 9 5 August 2021 – 9 January 2022 This exhibition has been curated by the University of Adelaide Library PLAY WITH PRIDE IMAGE LIST 1 5 7 9 The Cloisters Darling West The Braggs Engineering South Adelaide University Mixed Intervarsity Cricket Team, Intervarsity Swimming Intervarsity Football Club, Football Team, 1969 1925 Team, 1935 1961 Chosen by: Michelle Wilson, Chosen by: Rob O’Shannassy, Chosen by: Michael Physick, Chosen by: Beth Filmer, Adelaide Adelaide University Sport and Adelaide University Cricket Club University Representative on the University Football Club Member, Fitness General Manager Historian and former Player, Blues Board of Adelaide University Sport former Adelaide University Award Winner 1968, Adelaide and Fitness 2003-present Badminton Player This is a joyful photograph University Cricket Club Blues capturing the spirit of community Committee Member 1972-present While there have been few The 1960s was a golden era for the and sport. The diversity in 3 changes to many sports over the Adelaide University Football Club participation it represents is quite Photo of the 1925 Intervarsity team past 125 years, there have been under coach Allan Greer (1960-67). amazing for AFL as it predates the Union House that defeated Sydney in December many changes in the uniforms.