The Story of Ferdinand: the Implication of a Peaceful Bull

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Margaret Becker Seabee Battalion Repairs Eroding Cliffline

March 25, 2021 Volume 31, Issue 6 U.S. Naval Activities Spain No Mother Left Seabee Battalion DGF Senior Selected Behind: Margaret Repairs Eroding as Navy Finalist in Becker Cliffline Military Child of the Page 4 Page 12 Year Award Page 18 2 March 25, 2021 | COASTLINE Leadership Corner A Message from the Installation Safety Officer COASTLINE STAFF First of all, safely. That text or phone call can wait until you get to your I would like to destination and are safely stopped and parked. Thanks! Commanding Officer recognize the Our safety focus this year has been on risk identification, Capt. David S. Baird Naval Station risk assessment and risk reduction and will continue to be our Executive Officer (NAVSTA) focus moving forward. Annual risk assessments (RA) are the Cmdr. Justin Canfield Rota Safety cornerstone of a sound safety program. The RAs are what Department who drive the services we provide to you, our customers, based Command Master Chief CMDCM Kimberly Ferguson works tirelessly on the hazards and risks you are exposed to while performing each and every your important job tasks in support of our warfighting team. Public Affairs Officer day to ensure There are currently seven safety professionals in the Lt. Lyndsi Gutierrez we are providing department but we cannot be everywhere and see everything, [email protected] 727-1680 Team Rota with especially during reduced manning due to COVID. This is why the most current, we must rely on you, the members of Team Rota, to help us as Deputy Public Affairs Officer timely and our eyes and ears. -

Ferdinand the Bull

Ferdinand The Bull Educator Study & Performance Guide Table of Contents Table of Contents 2 About the guide, Inspiration behind the ballet, Credits 3 Standards Met by viewing Nashville Ballet’s Ferdinand the Bull 4 Pre Performance Discussion and Topics and Research 5-6 During the performance observations 7 Post Performance Reflection 8 Classroom Activities Speak Like a Matador - Literacy 9 Class Guided Tour – Literacy 10 Ferdinand’s Flower Garden – Literacy and Science 11 Ferdinand’s Flowers and Friends – Literacy and Science 11 Create Your Own Funny Hat- Visual Art 12 Become a Young Picasso – Visual Art 13 Become the Rhythm – Music 14 2 About the Ferdinand The Bull Educator Guide This guide is designed to enhance your performance experience by connecting our presentation to the classroom. You will find pre- and post- performance discussion topics designed to guide students as they watch the performance and later interpret it for themselves. You will also find suggested lesson plans and activities that meet the academic standards set forth by the State of Tennessee. Each of these lesson plans can be modified as you see fit to accommodate students, pre-K to 5th grade. We hope you find this guide helpful in creating a well-rounded experience for you and your students, and, more importantly, we hope it begins to create and foster a lifelong passion and enthusiasm for the arts for your students. The Inspiration Behind Nashville Ballet’s Ferdinand The Bull Nashville Ballet’s Ferdinand The Bull is inspired by The Story of Ferdinand, the heartwarming tale of a mild mannered Spanish fighting bull who would much rather sit peacefully and smell wild flowers than fight with the other bulls. -

The Story of Ferdinand by Munro Leaf Questions for Socratic Discussion by Adam and Missy Andrews

The Story of Ferdinand by Munro Leaf Questions for Socratic Discussion by Adam and Missy Andrews © 2006, The Center for Literary Education 3350 Beck Road Rice, WA 99167 (509) 738-6837 [email protected] www.centerforlit.com Contents Introduction 1 Questions about Context 3 Questions about Structure: Conflict and Plot 4 Questions about Structure: Setting 6 Questions about Structure: Characters 6 Questions about Structure: Theme 7 Story Chart 8 Introduction This teacher guide is intended to assist the teacher or parent in conducting meaningful discussions of literature in the classroom or home school. Questions and answers follow the pattern presented in Teaching the Classics , the Center for Literary Education’s two day literature seminar. Though the concepts underlying this approach to literary analysis are explained in detail in that seminar, the following brief summary presents the basic principles upon which this guide is based. The Teaching the Classics approach to literary analysis and interpretation is built around three unique ideas which, when combined, produce a powerful instrument for understanding and teaching literature: First: All works of fiction share the same basic elements — Context, Structure, and Style . A literature lesson that helps the student identify these elements in a story prepares him for meaningful discussion of the story’s themes. Context encompasses all of the details of time and place surrounding the writing of a story, including the personal life of the author as well as historical events that shaped the author’s world. Structure includes the essential building blocks that make up a story, and that all stories have in common: Conflict, Plot (which includes exposition , rising action , climax , denouement , and conclusion ), Setting, Characters and Theme. -

Houghtful Ooks

GRADES houghtful 2+ ooks Madison Moffatt A Teacher’s Guide to TheThe StoryStory ofof FerdinandFerdinand by Munro Leaf Social y Responsibilit Literac Series Editor Mary Abbott y Author Kirsten Lintott Note to parents and teachers The Thoughtful Books Series makes use of exemplary children’s literature to help young readers learn to read critically and to thoughtfully consider ethical matters. Critical thinkers rely on inquisitive attitudes, utilize thinking strategies, access background knowledge, understand thinking vocabulary, and apply relevant criteria when making thoughtful decisions. We refer to these attributes as intellectual tools. Each resource in this series features specific intellectual tools supporting literacy development and ethical deliberation. Teachers and parents can introduce the tools using the suggested activities in this resource, and then support learners in applying the tools in various situations overtime, until children use them independently, selectively, and naturally. Reading as thinking Reading is more than decoding words. It is the active process of constructing meaning. Good readers understand this process as engagement in critical thinking. They employ specific literacy competencies as they engage with text, create meaning from text, and extend their thinking beyond text. The activities in this booklet help develop the following literacy competencies: • Accessing background knowledge: Good readers draw on what they already know to establish a foun- dation for approaching new texts. In this case, the initial context of the story is bullfighting. Students discuss what they know about bullfighting in preparation for reading. • Reading with a purpose: Good readers are clear about why they are reading a text, either by bringing a specific objective to their reading or by anticipating the author’s objectives. -

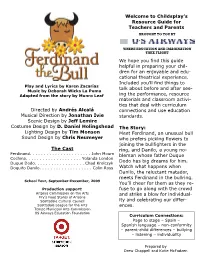

Ferdinand the Bull Resource Guide.Pub

Welcome to Childsplay’s Resource Guide for Teachers and Parents BROUGHT TO YOU BY WHERE EDUCATION AND IMAGINATION TAKE FLIGHT We hope you find this guide helpful in preparing your chil- dren for an enjoyable and edu- cational theatrical experience. Included you’ll find things to Play and Lyrics by Karen Zacarias talk about before and after see- Music by Deborah Wicks La Puma Adapted from the story by Munro Leaf ing the performance, resource materials and classroom activi- ties that deal with curriculum Directed by Andrés Alcalá connections and use education Musical Direction by Jonathan Ivie standards. Scenic Design by Jeff Lemire Costume Design by D. Daniel Holingshead The Story: Lighting Design by Tim Monson Meet Ferdinand, an unusual bull Sound Design by Chris Neumeyer who prefers picking flowers to joining the bullfighters in the The Cast ring, and Danilo, a young no- Ferdinand. John Moum bleman whose father Duque Cochina. Yolanda London Duque Dodo. Chad Krolczyk Dodo has big dreams for him. Doquito Danilo. Colin Ross Watch what happens when Danilo, the reluctant matador, meets Ferdinand in the bullring. School Tour, September-December, 2009 You’ll cheer for them as they re- Production support: fuse to go along with the crowd Arizona Commission on the Arts and strike a blow for individual- Fry’s Food Stores of Arizona Scottsdale Cultural Council ity and celebrating our differ- Scottsdale League for the Arts ences. Tempe Municipal Arts Commission US Airways Education Foundation Curriculum Connections: Page to stage – Spain – Spanish -

Leaf & Lawson: Story of Ferdinand PDF Book

LEAF & LAWSON: STORY OF FERDINAND PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Munro Leaf,Professor of Psychology Robert Lawson | 72 pages | 27 Jan 1983 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780670674244 | English | New York, NY, United States Leaf & Lawson: Story of Ferdinand PDF Book Sign in to Purchase Instantly. Play media. Halloween Books for Kids. Amy Krouse Rosenthal. When a shy high school student's body is found washed up on the shore of a quiet beach town - an apparent suicide - Terry Novak doesn't know what to think. Penguin Young Readers Group. One day, five men come to the pasture to choose a bull for the fights. Age Range: 2 - 5 Years. We are experiencing technical difficulties. Add to Cart. Her tooth He is a yaungol an oxen-like race who sits in a garden filled with flowers and trees, with a bouquet of flowers in each hand. Wells , Gandhi , and Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt. Some of his books have been brought back into print in recent years. See details. Cathy East Dubowski and Mark Dubowski. Uni the Unicorn and the Dream Come True. Two of them were published posthumously. Pass it on! However, when Ferdinand is let into the ring, he is delighted by the flowers in the ladies' hair and sits down in the middle of the ring to enjoy them, upsetting and disappointing everyone: "The Banderilleros were mad, and the Picadores were madder, and the matador was so mad he cried because he couldn't show off with his cape and sword. Related Searches. Although most of the illustrations are realistic, Lawson added touches of whimsy by adding, for instance, bunches of corks , as though plucked from a bottle, growing on the cork tree like fruit. -

Ceeds of Peace Elementary School Book List

Ceeds of Peace Elementary School Book List Books by Theme Anti-Bullying/Anger Management Anzin, Jennifer - The Incredible Shrinking Bully Anzin, Jennifer. The Incredible Shrinking Bully . CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2013. Print. Bang, Molly - When Sophie Gets Angry - Really, Really Angry... Bang, Molly. When Sophie Gets Angry-Really, Really Angry . New York: Blue Sky Press, 1999. Print. Criswell, Patti Kelley - A Smart Girl's Guide: Dealing with Fights, Being Left Out, and the Whole Popularity Thing. Criswell, Patti K, and Angela Martini. A Smart Girl's Guide: Dealing with Fights, Being Left Out, and the Whole Popularity Thing . , 2013. Print. dePaola, Tomie – Oliver Button Is a Sissy DePaola, Tomie. Oliver Button Is a Sissy . New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1979. Print. Havill, Juanita / Sibley O'Brien, Anne - Jamaica and Brianna Havill, Juanita, and Anne S. O'Brien. Jamaica and Brianna . Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1993. Print. Mcleod Humphrey, Sandra - Hot Issues, Cool Choices: Facing Bullies, Peer Pressure, Popularity and Put-Downs Humphrey, Sandra M. L. Hot Issues, Cool Choices!: Facing Bullies, Peer Pressure, Popularity and Put-Downs . Amherst, N.Y: Prometheus Books, 2007. Print. Moss, Peggy – Say Something Moss, Peggy, and Lea Lyon. Say Something . Gardiner, Me: Tilbury House, 2004. Print. Polacco, Patricia – Mr. Lincoln’s Way Polacco, Patricia. Mr. Lincoln's Way . New York: Philomel Books, 2001. Print. Urban, Linda / Cole, Henry - Mouse was Mad Urban, Linda, and Henry Cole. Mouse Was Mad . Orlando: Harcourt Children's Books, 2009. Print. Woodson, Jacqueline / Lewis, E.B. - Each Kindness Woodson, Jacqueline, and Earl B. Lewis. Each Kindness . New York: Nancy Paulsen Books, 2012. -

Producers Robert May and Lisa Marie Stetler to Be Honored at Northeast

Contact: Wendy Wilson, 570.840.0878 [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Producers Robert May and Lisa Marie Stetler to be honored at Northeast Pennsylvania Film Festival’s Gala Kickoff March 22nd Opening night festivities to feature encore screening of May’s “The Station Agent” Stetler to also headline “Pitch, Fund, Cast” panel discussion March 23 WAVERLY, PA (March 5, 2019) – A pair of national film producers with local ties will be honored at the Northeast Pennsylvania Film Festival’s Opening Night Gala slated for Friday, March 22, 7 p.m, at the Waverly Community House. Robert May, originally from Dallas, Pennsylvania, will receive the festival’s F. Lammot Belin Award for Excellence in Cinema. Lisa Maria Stetler, who hails from Waverly, Pennsylvania, will receive the festival's Vision Award during the festival’s opening-night festivities that will include cocktails and light fare. Tickets for the gala event are $65 in advance, $70 at the door and can be purchased online at nepafilmfestival.com or by calling 570-586-8191. An encore presentation of May's The Station Agent will be screened during the opening night gala with May introducing the film and hosting an audience Q + A after. May, originally from Dallas, PA, founded SenArt Films in 2000 with a focus on character-driven films. May has produced seven feature films to date which have collectively garnered over 40 awards including the Oscar®, BAFTA, Independent Spirit Award and Human Rights Award. May’s films include The Station Agent, directed by then first time director Tom McCarthy, which starred Peter Dinklage, Patricia Clarkson and Bobby Cannavale; The Fog of War (Errol Morris), Stevie (Steve James); The War Tapes (Deborah Scranton); and Bonnevile (Chris Rowley). -

Developing Character Through Literature: a Teacher's Resource Book

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 464 362 CS 511 101 TITLE Developing Character through Literature: A Teacher's Resource Book. INSTITUTION ERIC Clearinghouse on Reading, English, and Communication, Bloomington, IN.; Family Learning Association, Bloomington, IN. SPONS AGENCY Office of Educational Research and Improvement (ED), Washington, DC. ISBN ISBN-0-9719874-3-2 PUB DATE 2002-05-00 NOTE 187p. CONTRACT ED-99-CO-0028 AVAILABLE FROM ERIC Clearinghouse on Reading, English, and Communication, Indiana University, 2805 E. 10th Street, Suite 140, Bloomington, IN 47408-2698. Family Learning Association, 3925 Hagan St., Suite 101, Bloomington, IN 47401 (Order # 180-2199, $19.95). Tel: 800-759-4723 (Toll Free); Fax: 812-331-2776; Web site: http://kidscanlearn.com. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom - Teacher (052) -- ERIC Publications (071) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MFOl/PC08 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescent Literature; Annotated Bibliographies; *Childrens Literature; *Citizenship Education; Concept Formation; Elementary Secondary Education; *Individual Development; Learning Activities; *Values Education IDENTIFIERS *Character Development; Character Education; Family Activities; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Based on the idea that the most important foundation of education is character development, this book guides teachers and parents in building strong character traits while reading and discussing popular books. Children's books and young adult books draw students into discussions that can lead to action and to personal development. Thoughtful teachers and parents can ,use that literature and the activities suggested in.this book as a means of bringing their children to the commitments that will gradually form character traits and citizenship attitudes that everyone is proud to acknowledge. The units in the book stand for the most commonly described topics in character education: responsibility, honesty, integrity, respect, living peaceably, caring, civility, and the golden rule. -

Ferdinand the Bull

Ferdinand the Bull Education Pack Ages 8 - 10 1 CONTENTS How to use this Education Pack 2 LESSON 1: Listening to Music & Story 3 1.1 Music and feelings Listen to Ferdinand the Bull 3 How does the music make you feel? 3 Have you felt that way before? 3 1.2 New words New words 5 Adjectives and synonyms 5 1.3 Music and story Listen to the Matadors Arriving 7 How does the music change? 7 Programmatic Music 7 1.4 Music and Culture Music and culture 8 Rhythm in Ferdinand the Bull 8 Keep the rhythm! 8 About the Violin 9 1.5 Test Yourself 9 LESSON 2: Telling Stories & Making Music 10 2.1 Thinking about Stories 10 2.2 Write your own story! 11 2.3 Making Music! 13 3. Glossary 14 4. For Educators Further Resources, Background & Context 16 © Darwin Symphony Orchestra 2020 2 How to use this Education Pack Welcome to the Ferdinand the Bull Education Pack, designed to help teachers, educators and parents introduce kids to the delights of music and story. This pack accompanies DSO’s free recorded performance of Ferdinand the Bull written by Munro Leaf (words) and Alan Ridout (music). This performance features Tara Murphy on violin and Jonathan Tooby as the narrator. This Education Resource aims to deepen the way children understand this piece of music and to guide them towards writing their own narratives, which they can enliven with musical accompaniment. There are challenges and questions that ask them to think about what they hear from both a musical and a narrative point of view. -

Sciencedirect.Com Sciencedirect

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 212 ( 2015 ) 1 – 8 Prologue The 33rd International Conference of the Spanish Association of Applied Linguistics (AESLA) –XXXII Congreso Internacional de la Asociación Española de Lingüística Aplicada – was organized by the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid in 16-18 April 2015. The Conference, which was attended by over 500 participants, provided an international forum to multimodality so as to give a better understanding of this complex interdisciplinary area. The purpose of this Conference, “Multimodal Communication in the 21st Century: Professional and Academic Challenges”, was to study diverse communication practices in terms of the textual, aural, linguistic, spatial, and visual resources - or modes - used to compose texts in professional and academic contexts. The multiplicity of communication channels or modes is one of the most striking features of the new millennium. Verbal communication is only one of the various modes through which we can communicate and to put forward adequate scientific tools to analyse visual, gestural, body, cultural, or social networks language has become essential. The contributions of this conference have shed some light on these aspects and also on their influence on the academic and professional spheres. The Spanish Association of Applied Linguistics (AESLA) is well-known for trying to meet the ever-changing societal and industrial needs in the education of students. This constitutes a constant challenge towards which the celebration of this forum has collaborated with two plenary lectures devoted to multimodality in comics and translation whose content is briefly described below and selected papers which contribute new insights on the creation of meaning to the field of multimodal communication. -

Munro Leaf Papers, 1918-1986 FLP.RBD.LEAF Finding Aid Prepared by Caitlin Goodman

Munro Leaf papers, 1918-1986 FLP.RBD.LEAF Finding aid prepared by Caitlin Goodman This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit September 14, 2016 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Free Library of Philadelphia: Rare Book Department Philadelphia, PA, 19103 Munro Leaf papers, 1918-1986 FLP.RBD.LEAF Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Biographical/Historical note.......................................................................................................................... 5 Scope and Contents note............................................................................................................................... 6 Arrangement note...........................................................................................................................................6 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................7 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................ 7 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................8 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................