Long Term Regional Disparities [PDF, 53

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The German North Sea Ports' Absorption Into Imperial Germany, 1866–1914

From Unification to Integration: The German North Sea Ports' absorption into Imperial Germany, 1866–1914 Henning Kuhlmann Submitted for the award of Master of Philosophy in History Cardiff University 2016 Summary This thesis concentrates on the economic integration of three principal German North Sea ports – Emden, Bremen and Hamburg – into the Bismarckian nation- state. Prior to the outbreak of the First World War, Emden, Hamburg and Bremen handled a major share of the German Empire’s total overseas trade. However, at the time of the foundation of the Kaiserreich, the cities’ roles within the Empire and the new German nation-state were not yet fully defined. Initially, Hamburg and Bremen insisted upon their traditional role as independent city-states and remained outside the Empire’s customs union. Emden, meanwhile, had welcomed outright annexation by Prussia in 1866. After centuries of economic stagnation, the city had great difficulties competing with Hamburg and Bremen and was hoping for Prussian support. This thesis examines how it was possible to integrate these port cities on an economic and on an underlying level of civic mentalities and local identities. Existing studies have often overlooked the importance that Bismarck attributed to the cultural or indeed the ideological re-alignment of Hamburg and Bremen. Therefore, this study will look at the way the people of Hamburg and Bremen traditionally defined their (liberal) identity and the way this changed during the 1870s and 1880s. It will also investigate the role of the acquisition of colonies during the process of Hamburg and Bremen’s accession. In Hamburg in particular, the agreement to join the customs union had a significant impact on the merchants’ stance on colonialism. -

Family Gender by Club MBR0018

Summary of Membership Types and Gender by Club as of November, 2013 Club Fam. Unit Fam. Unit Club Ttl. Club Ttl. Student Leo Lion Young Adult District Number Club Name HH's 1/2 Dues Females Male Total Total Total Total District 111NW 21495 CLOPPENBURG 0 0 10 41 0 0 0 51 District 111NW 21496 DELMENHORST 0 0 0 36 0 0 0 36 District 111NW 21498 EMDEN 0 0 1 49 0 0 0 50 District 111NW 21500 MEPPEN-EMSLAND 0 0 0 44 0 0 0 44 District 111NW 21515 JEVER 0 0 0 42 0 0 0 42 District 111NW 21516 LEER 0 0 0 44 0 0 0 44 District 111NW 21520 NORDEN/NORDSEE 0 0 0 47 0 0 0 47 District 111NW 21524 OLDENBURG 0 0 1 48 0 0 0 49 District 111NW 21525 OSNABRUECK 0 0 0 49 0 0 0 49 District 111NW 21526 OSNABRUECKER LAND 0 0 0 35 0 0 0 35 District 111NW 21529 AURICH-OSTFRIESLAND 0 0 0 42 0 0 0 42 District 111NW 21530 PAPENBURG 0 0 0 41 0 0 0 41 District 111NW 21538 WILHELMSHAVEN 0 0 0 35 0 0 0 35 District 111NW 28231 NORDENHAM/ELSFLETH 0 0 0 52 0 0 0 52 District 111NW 28232 WILHELMSHAVEN JADE 0 0 1 39 0 0 0 40 District 111NW 30282 OLDENBURG LAPPAN 0 0 0 56 0 0 0 56 District 111NW 32110 VECHTA 0 0 0 49 0 0 0 49 District 111NW 33446 OLDENBURGER GEEST 0 0 0 34 0 0 0 34 District 111NW 37130 AMMERLAND 0 0 0 37 0 0 0 37 District 111NW 38184 BERSENBRUECKERLAND 0 0 0 23 0 0 0 23 District 111NW 43647 WITTMUND 0 0 10 22 0 0 0 32 District 111NW 43908 DELMENHORST BURGGRAF 0 0 12 25 0 0 0 37 District 111NW 44244 GRAFSCHAFT BENTHEIM 0 0 0 33 0 0 0 33 District 111NW 44655 OSNABRUECK HEGER TOR 0 0 2 38 0 0 0 40 District 111NW 45925 VAREL 0 0 0 30 0 0 0 30 District 111NW 49240 RASTEDE -

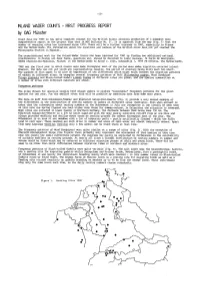

INLAND WADER COUNTS &Hyphen; FIRST PROGRESS REPORT

-20- INLAND WADER COUNTS- FIRST PROGRESSREPORT by OA6Mi]nsfer Count data for 1980 is now quite cc•plete (except for the British Isles) allowing production of a sc•what more cc•prehensive report on the project than that in WSGBulletin No. 31. It is apparent from the map (Fig. 1) that the number of counting sites has increased since 1979. There will be a further increase in 1981, especially in France and the Netherlands. The information about the locations and numbers of the British sites have not yet reached the BiologischeStation in M•nster. The organisational work for the Inland Wader Counts has been improved for 1981 by finding two additional national coordinators: in France all data forms, questions etc. should be directed to Alain Sauvage, 14 Porte de Bourgogne, 08000Charleville-Mezi•res, France; in the Netherlandsto Arendv. Dijk, Ootmandijk1, 7975 PRUffelte, The Netherlands. 1980 was the first year in which counts were made throughout most of the period when wader migration occurred inland. However, the data can not yet yield any representative results, the period of counting being still much too short. The purpose of this paper is to give an impression of the differences which might exist between the migration patterns of waders at different sites. As examples several frequency patterns of Ruff Philc•achus pugnax, Wood Sandpiper Tringa glareola and Black-tailed Godwit Limosa limosa at different sites are given, and the species cc•munities at a number of sites with different habitats are s•hown. Frequency patterns The sites chosen for analysis usually held enough waders to produce "reasonable" frequency patterns for the given species for one year. -

Mitgliedschaft Des Landkreises Cloppenburg in Gesellschaften, Körperschaften, Verbänden Und Vereinen

Kreisrecht Mitgliedschaft des Landkreises Cloppenburg in Gesellschaften, Körperschaften, Verbänden und Vereinen Lfd. Nr. Bezeichnung Amt 1 Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Jugendämter der Länder Nieder- 50 sachsen und Bremen (AGJÄ) 2 Arbeitsgemeinschaft Peripherer Regionen Deutschlands WI (APER) 3 Bezirksverband Oldenburg 10 4 Bundesarbeitsgemeinschaft der LEADER-Aktionsgruppen WI (BAG-LEADER) 5 Bundesverband für Wohnen und Stadtentwicklung e.V. 10 (vhw) 6 Caritas Verein Altenoythe 50 7 c-Port Hafenbesitz GmbH 20 8 Deutscher Verein für öffentliche und private Fürsorge e.V. 50 9 Deutsches Institut für Jugendhilfe und Familienrecht e.V. 51 (DIJuF) 10 Deutsches Institut für Lebensmitteltechnik 10 11 Deutsche Vereinigung für Wasserwirtschaft, Abwasser und 70 Abfall e.V. (DWA) 12 Ems-Weser-Elbe Versorgungs- und Entsorgungsverband 20 13 Energienetzwerk Nordwest (ENNW) 40 14 Fachverband der Kämmerer in Niedersachsen e.V. 20 15 FHWT Vechta-Diepholz-Oldenburg, Private Fachhochschule WI für Wirtschaft und Technik 16 Förder- und Freundeskreis psychisch Kranker im Landkreis 53 Cloppenburg e.V. 17 Gemeinde-Unfallversicherungsverband (GUV) 10 18 Gemeinsame Einrichtung gemäß § 44 b SGB II (Jobcenter) 50 19 Gemeinschaft DAS OLDENBURGER LAND WI 19 Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Gewinnung von Energie aus 20 Biomasse der Agrar- und Ernährungswirtschaft mbH (GEA) 20 Großleitstelle Oldenburger Land 32 21 Grünlandzentrum Niedersachsen/Bremen e.V. 67 22 GVV Kommunalversicherung VVaG 10 23 Heimatbund für das Oldenburger Münsterland e.V. 40 24 Historische Kommission für Niedersachsen und Bremen e.V. 40 25 Interessengemeinschaft „Deutsche Fehnroute e.V.“ WI 26 Kommunale Datenverarbeitung Oldenburg (KDO) 10 27 Kommunale Gemeinschaftsstelle für Verwaltungsmanage- 10 ment (KGSt) 28 Kommunaler Arbeitgeberverband Niedersachsen e.V. 10 (KAV) 29 Kommunaler Schadenausgleich Hannover (KSA) 20 30 Kreisbildungswerk Cloppenburg – Volkshochschule für den 40 Landkreis Cloppenburg e.V. -

The London Gazette, 30 June, 1911

4.834 THE LONDON GAZETTE, 30 JUNE, 1911. Richard Howard Mortimore, Esq., to be His Foreign Office, Majesty's Consul-General for the Consular June 16, 1911. District of Chengtu, to reside at Chengtu; Harry Halton Fox, Esq., to be His Majesty's The KING has been pleased to approve of— Consul for the Consular District of Chefoo, to reside at Chefoo; Senor Don Eduardo L. Colombres as Consul- General of the Argentine Republic at Berthold George Tours, Esq., to be His Calcutta; Majesty's Consul for the Consular District of Wuhu, to reside at Wuhu; Monsieur L. Vincart as Consul-General of Belgium for British Guiana; John Langford Smith, Esq., to be His Majesty's Consul for the Consular District Mr. William Meek as Consul of Norway afc of Tengyueh, to reside at Tengyueh; and Aden; Harold Porter, Esq., to be one of His Majesty's Dr. Herbert Walker as Vice-Consul of Vice-Consuls in China. Uruguay at Bedford; and Mr. N. A. Outerbridge as Vice-Consul of the Netherlands at St. John's for the Colony of Newfoundland. Foreign Office, June 2, 1911. The KING has been graciously pleased to appoint— Foreign Office, June 22, 1911. Walter Risley Hearn, Esq., to be His Majesty's Consul-General for the free cities and terri- The KING has been graciously pleased to tories of Hamburg, Lubeck and Bremen, the appoint— Province of Schleswig-Holstein with Lauen- berg, the Grand Duchies of Mecklenburg- Charles Alfred Payton, Esq., M.V.O., to be Schwerin and Mecklenburg-Strelitz, the His Majesty's Consul-General for the De- Grand Duchy of Oldenburg, the District of partments of Nord (with the exception of the Wilhelmshaven, the Province of Hanover, the Town, Port and Arrondissement of Dun- Duchy of Brunswick, and the Principalities dirk), Pas-de-Calais, Somme, Aisne, and of Lippe-Schaumburg, Lippe-Detmold, and Ardennes, to reside at Calais. -

Hier Sind Die Könner Zu Hause!

WESERMARSCH – HIER SIND DIE KÖNNER ZU HAUSE! Wirtschaftsstandort Wesermarsch – überraschend anders UNSERE WESERMARSCH KRISENSICHER | GRÜN | ZUKUNFTSORIENTIERT FAMILIE: Ein echter Heimathafen für ein sicheres Lebensgefühl BETRIEBE: Traditiontrifft trifft UMWELT: Innovation– – Grünland, grüne unsere Könner Energieregion, schaffenLösungen Lösungen grüner Wasserstoff: für Generationen Nachhaltigkeit lebt von bewussten Entscheidungen 2 | www.landkreis-wesermarsch.de www.wesermarsch.de Foto: Fassmer UNSERE WESERMARSCH KRISENSICHER | GRÜN | ZUKUNFTSORIENTIERT LIEBE LESERINNEN, LIEBE LESER! INHALT/EDITORIAL/IMPRESSUM INHALT Was bedeutet es, auf regionaler Ebene die Wirtschaft zu fördern? In Gablers Wirtschaftslexikon heißt es dazu: UNSERE LAGE SORGT IMMER FÜR FRISCHEN WIND – „Wirtschaftsförderung ist die Erhaltung 05 ZUM GELD VERDIENEN UND IDEEN ENTWICKELN oder Stärkung der kommunalen Wirt- schaftskraft, die Verbesserung des Arbeitsplatzangebots (…) Die für die ENERGIEWENDE 2.0: Praxis wichtigsten Formen können als 11 BESTE PERSPEKTIVEN ALS „DIE“ H2-REGION Bestandspflege sowie als Ansiedlungs- politik (Standortmarketing) bezeichnet werden.“ DIE MISCHUNG MACHT‘S: 15 ATTRAKTIV UND LEISTUNGSSTARK ENTLANG DER WESER Erfüllen wir als Wirtschaftsförderung diesen Auftrag? Wir meinen: Ja. Wir unterstreichen das jeden Tag in der INTERKOMMUNALES GEWERBEGEBIET: partnerschaftlichen Zusammenarbeit, 21 EINE 140 HEKTAR GROßE LANGFRISTIGE PERSPEKTIVE z. B. mit dem Landkreis und den kreis- eigenen Städten und Gemeinden, mit Unternehmen, Verbänden, Hochschulen FAMILIE: -

The Spatial and Temporal Diffusion of Agricultural Land Prices

The Spatial and Temporal Diffusion of Agricultural Land Prices M. Ritter; X. Yang; M. Odening Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Department of Agricultural Economics, Germany Corresponding author email: [email protected] Abstract: In the last decade, many parts of the world experienced severe increases in agricultural land prices. This price surge, however, did not take place evenly in space and time. To better understand the spatial and temporal behavior of land prices, we employ a price diffusion model that combines features of market integration models and spatial econometric models. An application of this model to farmland prices in Germany shows that prices on a county-level are cointegrated. Apart from convergence towards a long- run equilibrium, we find that price transmission also proceeds through short-term adjustments caused by neighboring regions. Acknowledegment: Financial support from the China Scholarship Council (CSC NO.201406990006) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) through Research Unit 2569 “Agricultural Land Markets – Efficiency and Regulation” is gratefully acknowledged. The authors also thank Oberer Gutachterausschuss für Grundstückswerte in Niedersachsen (P. Ache) for providing the data used in the analysis. JEL Codes: Q11, C23 #117 The Spatial and Temporal Diffusion of Agricultural Land Prices Abstract In the last decade, many parts of the world experienced severe increases in agricultural land prices. This price surge, however, did not take place evenly in space and time. To better understand the spatial and temporal behavior of land prices, we employ a price diffusion model that combines features of market integration models and spatial econometric models. An application of this model to farmland prices in Germany shows that prices on a county-level are cointegrated. -

Regionale Dienststelle Friesland-Wilhelmshaven

Gemeinsame Kirchenverwaltung Regionale Dienststelle Friesland-Wilhelmshaven Stand: 04.01.2021 Regionale Dienststelle Friesland Wilhelmshaven Regionale Dienststelle Friesland-Wilhelmshaven Olympiastr. 1 26419 Schortens Postfach: 2125, 26414 Schortens Telefon: 0 44 21 / 7 74 49 26 00 Durchwahl: 0 44 21 / 7 74 49 26 + Nebenstelle Zentrales Fax: 0 44 21 / 7 74 49 26 14 Zentrale E-Mail: [email protected] Öffnungszeiten: Montag bis Donnerstag 9.00 – 12.00 Uhr und 14.00 – 15.00 Uhr Freitag 9.00 – 13.00 Uhr (und nach Vereinbarung) Hinweis: Individuelle, abweichende Arbeitszeiten finden Sie auf den nachfolgenden Seiten der jeweiligen MitarbeiterInnen. 2 Regionale Dienststelle Friesland Wilhelmshaven DIENSTSTELLENLEITUNG Burkhard Streich Die Regionale Dienststelle Friesland-Wilhelmshaven ist die Verwaltungsstelle der Ev.-Luth. Kir- che in Oldenburg für den Kirchenkreis Friesland-Wilhelmshaven und dessen Kirchengemeinden und Einrichtungen. Von den Mitarbeiterinnen und Mitarbeitern werden Bau-, Finanz-, Fried- hofs-, Kindertagesstättenbeitrags-, Liegenschafts- und Personalangelegenheiten bearbeitet. Die Regionale Dienststelle Friesland-Wilhelmshaven bildet mit den fünf weiteren Regionalen Dienststellen und der Zentralen Dienststelle die Gemeinsame Kirchenverwaltung der Ev.-Luth. Kirche in Oldenburg. Hier entstehen Dienst-, Miet- und Pachtverträge, Satzungen für Gebühren zur Nutzung von Kindertagestätten und Friedhöfen, Haushalts- und Stellenpläne. Im Rahmen der Rechtmäßigkeitsprüfung kann die Regionale Dienststelle -

Lions Clubs International Club Membership Register

LIONS CLUBS INTERNATIONAL CLUB MEMBERSHIP REGISTER SUMMARY THE CLUBS AND MEMBERSHIP FIGURES REFLECT CHANGES AS OF SEPTEMBER 2019 MEMBERSHI P CHANGES CLUB CLUB LAST MMR FCL YR TOTAL IDENT CLUB NAME DIST NBR COUNTRY STATUS RPT DATE OB NEW RENST TRANS DROPS NETCG MEMBERS 3499 021495 CLOPPENBURG GERMANY 111NW 4 09-2019 50 0 0 0 0 0 50 3499 021496 DELMENHORST GERMANY 111NW 4 09-2019 38 0 0 0 0 0 38 3499 021498 EMDEN GERMANY 111NW 4 09-2019 51 2 0 0 0 2 53 3499 021500 MEPPEN-EMSLAND GERMANY 111NW 4 09-2019 41 0 0 0 0 0 41 3499 021515 JEVER GERMANY 111NW 4 09-2019 42 0 0 0 0 0 42 3499 021516 LEER GERMANY 111NW 4 09-2019 47 0 0 0 0 0 47 3499 021520 NORDEN/NORDSEE GERMANY 111NW 4 08-2019 41 0 0 0 0 0 41 3499 021524 OLDENBURG GERMANY 111NW 4 06-2019 45 0 0 0 0 0 45 3499 021525 OSNABRUECK GERMANY 111NW 4 08-2019 55 1 0 0 0 1 56 3499 021526 OSNABRUECKER LAND GERMANY 111NW 4 07-2019 37 0 0 0 0 0 37 3499 021529 AURICH-OSTFRIESLAND GERMANY 111NW 4 09-2019 43 0 0 0 0 0 43 3499 021530 PAPENBURG GERMANY 111NW 4 09-2019 40 1 0 0 0 1 41 3499 021538 WILHELMSHAVEN GERMANY 111NW 4 09-2019 42 0 0 0 0 0 42 3499 028231 NORDENHAM/ELSFLETH GERMANY 111NW 4 09-2019 44 1 0 0 0 1 45 3499 028232 WILHELMSHAVEN JADE GERMANY 111NW 4 09-2019 37 0 0 0 0 0 37 3499 030282 OLDENBURG LAPPAN GERMANY 111NW 4 06-2019 59 0 0 0 0 0 59 3499 032110 VECHTA GERMANY 111NW 4 09-2019 52 1 0 0 0 1 53 3499 033446 OLDENBURGER GEEST GERMANY 111NW 4 09-2019 37 0 0 0 0 0 37 3499 037130 AMMERLAND GERMANY 111NW 4 09-2019 36 0 0 0 0 0 36 3499 038184 BERSENBRUECKERLAND GERMANY 111NW 4 09-2019 25 0 -

The War and Fashion

F a s h i o n , S o c i e t y , a n d t h e First World War i ii Fashion, Society, and the First World War International Perspectives E d i t e d b y M a u d e B a s s - K r u e g e r , H a y l e y E d w a r d s - D u j a r d i n , a n d S o p h i e K u r k d j i a n iii BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA 29 Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2, Ireland BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2021 Selection, editorial matter, Introduction © Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian, 2021 Individual chapters © their Authors, 2021 Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identifi ed as Editors of this work. For legal purposes the Acknowledgments on p. xiii constitute an extension of this copyright page. Cover design by Adriana Brioso Cover image: Two women wearing a Poiret military coat, c.1915. Postcard from authors’ personal collection. This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Licence. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third- party websites referred to or in this book. -

4.4-2 Lower Saxony WS Region.Pdf

chapter4.4_Neu.qxd 08.10.2001 16:11 Uhr Seite 195 Chapter 4.4 The Lower Saxony Wadden Sea Region 195 near Sengwarden have remained fully intact. The With the exception of the northern section’s water tower on „Landeswarfen“ west of tourist visitors, the Voslapper Groden mainly Hohenkirchen is a landmark visible from a great serves as a sea rampart for Wilhelmshaven’s distance, constructed by Fritz Höger in 1936 to commercial buildings, a function also served by serve as Wangerooge’s water supply. the Rüstersieler Groden (1960-63) and the Hep- Of the above-mentioned scattered settlements penser Groden, first laid out as a dyke line from characteristic to this region, two set themselves 1936-38, although construction only started in physically apart and therefore represent limited 1955. It remains to be seen whether the histori- forms within this landscape. cally preserved parishes of Sengwarden and Fed- Some sections of the old dyke ring whose land derwarden, now already part of Wilhelmshaven, was considered dispensable from a farming or will come to terms with the consequences of this land ownership perspective served as building and the inexorable urban growth through appro- space for erecting small homes of farm labourers priate planning. and artisans who otherwise made their homes in The cultural landscape of the Wangerland and small numbers on larger mounds. Among these the Jeverland has been able to preserve its were the „small houses“ referred to in oral tradi- unmistakable character to a considerable degree. tion north of Middoge, the Oesterdeich (an early The genesis of landscape forms is mirrored in the groden dyke), the Medernser Altendeich, the patterns of settlement, the lay of arable land and Norderaltendeich and foremost the area west of in landmark monuments. -

Supplement of Storm Xaver Over Europe in December 2013: Overview of Energy Impacts and North Sea Events

Supplement of Adv. Geosci., 54, 137–147, 2020 https://doi.org/10.5194/adgeo-54-137-2020-supplement © Author(s) 2020. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Supplement of Storm Xaver over Europe in December 2013: Overview of energy impacts and North Sea events Anthony James Kettle Correspondence to: Anthony James Kettle ([email protected]) The copyright of individual parts of the supplement might differ from the CC BY 4.0 License. SECTION I. Supplement figures Figure S1. Wind speed (10 minute average, adjusted to 10 m height) and wind direction on 5 Dec. 2013 at 18:00 GMT for selected station records in the National Climate Data Center (NCDC) database. Figure S2. Maximum significant wave height for the 5–6 Dec. 2013. The data has been compiled from CEFAS-Wavenet (wavenet.cefas.co.uk) for the UK sector, from time series diagrams from the website of the Bundesamt für Seeschifffahrt und Hydrolographie (BSH) for German sites, from time series data from Denmark's Kystdirektoratet website (https://kyst.dk/soeterritoriet/maalinger-og-data/), from RWS (2014) for three Netherlands stations, and from time series diagrams from the MIROS monthly data reports for the Norwegian platforms of Draugen, Ekofisk, Gullfaks, Heidrun, Norne, Ormen Lange, Sleipner, and Troll. Figure S3. Thematic map of energy impacts by Storm Xaver on 5–6 Dec. 2013. The platform identifiers are: BU Buchan Alpha, EK Ekofisk, VA? Valhall, The wind turbine accident letter identifiers are: B blade damage, L lightning strike, T tower collapse, X? 'exploded'. The numbers are the number of customers (households and businesses) without power at some point during the storm.