Article Full Text

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Town of Lake Arthur "Nature's Beauty Spot"

TOWN OF LAKE ARTHUR "NATURE'S BEAUTY SPOT" MAYOR SHERRY CROCHET COUNCIL MEMBERS: DAVID HANKS RICKY MONCEAUX ROBERT PALERMO AULDON ROBINSON SAMPSON LEJEUNE CHIEF OF POLICE TOWN CLERK TOWN ATTORNEY COURT MAGISTRATE KOBI B. TURNER MINDY MARCANTEL BENNETT LAPOINT RICHARD ARCENEAUX NOTICE POSTED: JUNE 25, 2021 TIME POSTED: NOTICE OF PUBLIC HEARING A public meeting will be held as follows: DATE: JUNE 29, 2021 TIME: 9:00 AM PLACE OF MEETING: City Hall: 102 Arthur Ave Lake Arthur, LA 70549 BUDGET HEARING Discussion of Budget Introduce Ordinance No. 596, An Ordinance adopting and enacting a budget of revenues, expenditures and transfers for the Town of Lake Arthur, Louisiana for the fiscal year of 2021 and 2022. AGENDA SPECIAL MEETING 1. Call to Order 2. Prayer 3. Pledge of Allegiance 4. Roll Call 5. Motion to Adopt Agenda 6. Citizen Agenda Item: Open Discussion Re: Garbage collection, fees, quotes to contract services, etc. with representatives from Dillion Disposal, President Jordan Danna and Charles LaGrange, Municipal Sales Manager with Republic Services 7. Motion to Approve minutes of Special Meeting held June 4, 2021, as submitted. 8. Motion to introduce Ordinance No. 596, An Ordinance Amending Ordinance No. 560, Enacting a Budget of Revenues, Expenditures, and Transfers for the Town of Lake Arthur for Fiscal year August 1, 2021, and Ending July 31, 2022 9. Motion to Adjourn meeting Mindy Marcantel; Clerk Town of Lake Arthur 102 Arthur Ave, Lake Arthur, LA 70549 337-774-2211 In accordance with the Americans with Disabilities Act, if you need special assistance, please contact Mindy Marcantel at 337- 774-2211 describing the assistance that is necessary. -

Hooray for Health Arthur Curriculum

Reviewed by the American Academy of Pediatrics HHoooorraayy ffoorr HHeeaalltthh!! Open Wide! Head Lice Advice Eat Well. Stay Fit. Dealing with Feelings All About Asthma A Health Curriculum for Children IS PR O V IDE D B Y FUN D ING F O R ARTHUR Dear Educator: Libby’s® Juicy Juice® has been a proud sponsor of the award-winning PBS series ARTHUR® since its debut in 1996. Like ARTHUR, Libby’s Juicy Juice, premium 100% juice, is wholesome and loved by kids. Promoting good health has always been a priority for us and Juicy Juice can be a healthy part of any child’s balanced diet. Because we share the same commitment to helping children develop and maintain healthy lives, we applaud the efforts of PBS in producing quality educational television. Libby’s Juicy Juice hopes this health curriculum will be a valuable resource for teaching children how to eat well and stay healthy. Enjoy! Libby’s Juicy Juice ARTHUR Health Curriculum Contents Eat Well. Stay Fit.. 2 Open Wide! . 7 Dealing with Feelings . 12 Head Lice Advice . 17 All About Asthma . 22 Classroom Reproducibles. 30 Taping ARTHUR™ Shows . 32 ARTHUR Home Videos. 32 ARTHUR on the Web . 32 About This Guide Hooray for Health! is a health curriculum activity guide designed for teachers, after-school providers, and school nurses. It was developed by a team of health experts and early childhood educators. ARTHUR characters introduce five units exploring five distinct early childhood health themes: good nutrition and exercise (Eat Well. Stay Fit.), dental health (Open Wide!), emotions (Dealing with Feelings), head lice (Head Lice Advice), and asthma (All About Asthma). -

Kids with Asthma Can! an ACTIVITY BOOKLET for PARENTS and KIDS

Kids with Asthma Can! AN ACTIVITY BOOKLET FOR PARENTS AND KIDS Kids with asthma can be healthy and active, just like me! Look inside for a story, activity, and tips. Funding for this booklet provided by MUSEUMS, LIBRARIES AND PUBLIC BROADCASTERS JOINING FORCES, CREATING VALUE A Corporation for Public Broadcasting and Institute of Museum and Library Services leadership initiative PRESENTED BY Dear Parents and Friends, These days, almost everybody knows a child who has asthma. On the PBS television show ARTHUR, even Arthur knows someone with asthma. It’s his best friend Buster! We are committed to helping Boston families get the asthma care they need. More and more children in Boston these days have asthma. For many reasons, children in cities are at extra risk of asthma problems. The good news is that it can be kept under control. And when that happens, children with asthma can do all the things they like to do. It just takes good asthma management. This means being under a doctor’s care and taking daily medicine to prevent asthma Watch symptoms from starting. Children with asthma can also take ARTHUR ® quick relief medicine when asthma symptoms begin. on PBS KIDS Staying active to build strong lungs is a part of good asthma GO! management. Avoiding dust, tobacco smoke, car fumes, and other things that can start an asthma attack is important too. We hope this booklet can help the children you love stay active with asthma. Sincerely, 2 Buster’s Breathless Adapted from the A RTHUR PBS Series A Read-Aloud uster and Arthur are in the tree house, reading some Story for B dusty old joke books they found in Arthur’s basement. -

Children's Catalog

PBS KIDS Delivers! Emotions & Social Skills Character Self-Awareness Literacy Math Science Source: Marketing & Research Resources, Inc. (M&RR,) January 2019 2 Seven in ten children Research shows ages 2-8 watch PBS that PBS KIDS makes an in the U.S. – that’s impact on early † childhood 19 million children learning** * Source: Nielsen NPower, 1/1/2018--12/30/2018, L+7 M-Su 6A-6A TP reach, 50% unif., 1-min, LOH18-49w/c<6, LOH18-49w/C<6 Hispanic Origin. All PBS Stations, children’s cable TV networks ** Source: Hurwitz, L. B. (2018). Getting a Read on Ready to Learn Media: A Meta-Analytic Review of Effects on Literacy. Child Development. Dol:10.1111/cdev/f3043 † Source: Marketing & Research Resources, Inc. (M&RR), January 2019 3 Animated Adventure Comedy! Dive into the great outdoors with Molly of Denali! Molly, a feisty and resourceful 10-year-old Alaskan Native, her dog Suki, and her Facts: friends Tooey and Trini take • Contemporary rural life advantage of their awe-inspiring • Intergenerational surroundings with daily relationships adventures. They also use • Respect for elders resources like books, maps, field • Set against a backdrop of guides, and local experts to Native America culture and encourage curiosity and help in traditions • Producers: Atomic Cartoons and their community. WGBH KIDS • Broadcaster: PBS KIDS Target Demo: 4 to 8 76 x 11’ (Delivered as 38 x 25') + 1 x 60’ special Watch Trailer Watch Full Episode 4 Exploring Nature’s Ingenious Inventions This funny and engaging show follows a curious bunny named Facts: Elinor as she asks the questions in • COMING FALL 2020 every child’s mind and discovers • Co-created by Jorge Cham and the wonders of the world around Daniel Whiteson, authors of We her. -

The “Babe” Vegetarians: Bioethics, Animal Minds and Moral Methodology

WellBeing International WBI Studies Repository 2009 The “Babe” Vegetarians: Bioethics, Animal Minds and Moral Methodology Nathan Nobis Morehouse College Follow this and additional works at: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/acwp_sata Part of the Animal Studies Commons, Other Anthropology Commons, and the Other Nutrition Commons Recommended Citation Nobis, N. (2009). The "Babe" vegetarians: bioethics, animal minds and moral methodology. In S. Shapshay (Ed.), Bioethics at the movies. Baltimore : Johns Hopkins University Press. (pp. 56-73). This material is brought to you for free and open access by WellBeing International. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The “Babe” Vegetarians: Bioethics, Animal Minds and Moral Methodology Nathan Nobis Morehouse College [email protected] “The fact is that animals that don't seem to have a purpose really do have a purpose. The Bosses have to eat. It's probably the most noble purpose of all, when you come to think about it.” – Cat, “Babe” "The animals of the world exist for their own reasons. They were not made for humans any more than black people were made for white, or women created for men." – Alice Walker 1. Animal Ethics as Bioethics According to bioethicist Paul Thompson, “When Van Rensselaer Potter coined the term ‘bioethics’ in 1970, he intended for it to include subjects ranging from human to environmental health, including not only the familiar medical ethics questions . but also questions about humanity's place in the biosphere” (Thompson, 2004). These latter questions include ethical concerns about our use of animals: morally, should animals be on our plates? Should humans eat animals? The fields of animal and agricultural ethics address these questions. -

Platform Delegate List

First Name Surname Job Title Company Email Suleeko Abdi Student [email protected] Frances Abebreseh Communications Manager Netflix Lucy Acfield Head of Brand & Product Marketing Guinness World Records James Acken Founder, Freelancer Acken Studios lindsey@dailymadnessproducti Lindsey Adams Producer Daily Madness ons.com Megan Adams Look Mentor Look UK ToyLikeMe Seleena Addai Illustrator / Character Designer The Secret Story Draw [email protected] Animation Production Liaison [email protected] Abigail Addison Executive ScreenSkills om Aiden Adkin Creative Director Harbour Bay [email protected] Selorm Adonu Director XVI Films [email protected] Ivan Agenjo Executive Producer Peekaboo Animation [email protected] Jayne Aguire Walsh Entry Level Creative Freelance [email protected] Andrew Aidman Producer Andrew Aidman [email protected] Sun In Eye Productions, Aittokoski Metsamarja Aittokoski Screenwriter, Director, Producer Experience [email protected] Sonja Ajdin Research Manager Viacom Yinka Akano CRBA Exec BBC [email protected] Production and Development Francesca Alberigi Coordinator Nickelodeon International Aoife Alder Research Executive ITV Candice Alessandra Student Student Laura Alexander Video Producer / Editor Acamar Films Kristopher Alexander Professor of Video Games The Digital Citadel [email protected] Lisa Ali Freelance Freelance Shakila Ali Content Impact BBC Co-Founder and Chief Creative Caroline Allams Officer Natterhub [email protected] Bill Allard -

Arthur WN Guide Pdfs.8/25

Building Global and Cultural Awareness Keep checking the ARTHUR Web site for new games with the Dear Educator: World Neighborhood ® ® has been a proud sponsor of the Libby’s Juicy Juice ® theme. RTHUR since its debut in award-winning PBS series A ium 100% 1996. Like Arthur, Libby’s Juicy Juice, prem juice, is wholesome and loved by kids. itment to a RTHUR’s comm Libby’s Juicy Juice shares A world in which all children and cultures are appreciated. We applaud the efforts of PBS in producingArthur’s quality W orld educational television and hope that Neighborhood will be a valuable resource for teaching children to understand and reach out to one another. Enjoy! Libby’s Juicy Juice Contents About This Guide. 1 Around the Block . 2 Examine diversity within your community Around the World. 6 Everyday Life in Many Cultures: An overview of world diversity Delve Deeper: Explore a specific culture Dear Pen Pal . 10 Build personal connections through a pen pal exchange More Curriculum Connections . 14 Infuse your curriculum with global and cultural awareness Reflections . 15 Reflect on and share what you have learned Resources . 16 All characters and underlying materials (including artwork) copyright by Marc Brown.Arthur, D.W., and the other Marc Brown characters are trademarks of Marc Brown. About This Guide As children reach the early elementary years, their “neighborhood” expands beyond family and friends, and they become aware of a larger, more diverse “We live in a world in world. How are they similar and different from others? What do those which we need to share differences mean? Developmentally, this is an ideal time for teachers and providers to join children in exploring these questions. -

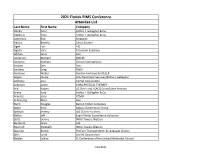

2021 Florida RIMS Conference Attendee List Last Name First Name Company Abella Ilene Arthur J

2021 Florida RIMS Conference Attendee List Last Name First Name Company Abella Ilene Arthur J. Gallagher & Co. Abella, Jr. Tony Arthur J. Gallagher & Co. Ackerman Rick Sedgwick Adkins Beverly Johns Eastern Agee Lori AIG Aguila Sara Transcom Solutions Allman Scott Aon Anderson Michael MKCM Andracic Kristijan Forcon International Andrea Dan Aon Andress Greg FWCI Andrews Walter Hunton Andrews Kurth LLP Anglin Nicole Risk Placement Services/Arthur J Gallagher Anthony Joni CorVel Corporation Arbelaez Jackie CORA PHYSICAL THERAPY Ard Robert US Omni and TSACG Compliance Services Arenz Judy Arthur J. Gallagher & Co. Armatis Jerry CCMSI Armstrong Marc Aon Baird Douglas Barron Collier Comanies Baker Kelly Asbury Automotive Group Baldwin Jeremy ISO Claims Partners Ballou Jeff Exam Works Compliance Solutions Baltz Dennis Willis Towers Watson Bambrick Drew AIG Bancroft Elizabeth Willis Towers Watson Baserap Brandi ProCare Transportation & Language Serices Bass Linda CorVel Corporation Battles LaNita FL Conference of the United Methodist Church 7/19/2021 2021 Florida RIMS Conference Attendee List Last Name First Name Company Bauer Saville Renata McLarens Beaver Alex Berkshire Hathaway Specialty Insurance Becksmith Josh Brown & Brown Bell Jennifer Aon Bell Stephen Diocese of St. Augustine Bellomo Michael Bloomin Brands Bennett Raymond StempleCrites Benz Mark AIG Insurance Management Services Benzinger Veronica Aon Bergeron Brenda Johns Eastern Berkbigler Angela Windham Group Bernardo Jamie North American Risk Services Bertizlian Carlos HealthCare Comp Bettini Shelby Lemieux & Associates Bew Monica Niki's Int'l Ltd. Bliss Jason Orchid Medical Boglioli Louis City of Stuart Borger Suzanne HCA Bouker Tammy Vernis & Bowling Boystov Stan Wright Rehabilitation Services, Inc. Brada Carolyn Martin County BOCC Bradley Leah Paul Davis Restoration Branson BJ PMA Companies Braun Melissa Alliance Risk Group, Inc. -

Réflexion Adressée À Madame Julie Lemieux, Ville De Québec

Terres patrimoniales de Sillery: plaidoyer pour le faubourg Saint-Michel Réflexion adressée à madame Julie Lemieux, Ville de Québec Nicole Dorion-Poussart, M.A. (histoire) Membre émérite de la Société d’histoire de Sillery Membre du Comité citoyen pour l’agriculture urbaine de Sillery Le 29 juin 2015 1. Historique du faubourg Le développement prodigieux de l’industrie du bois dans les anses de Sillery au cours de la première moitié du 19e siècle amène de nombreux ouvriers à habiter sur le chemin du Foulon, près des chantiers. En 1847, lorsque l’Angleterre adopte une politique de libre échange et abandonne ses tarifs préférentiels, plusieurs marchands de bois, dont Patrick McInenly, déclarent faillite. Propriétaire d’un vaste domaine qui s’étendait entre le chemin Saint-Louis et la Pointe-à- Puiseaux, et entre la Côte de l’Église et le domaine Jésus-Marie, McInenly cède la Pointe-à-Puiseaux et sa magnifique villa à l’archevêché de Québec. Quelques années plus tard, l’industrie du bois amorce son déclin, et les héritiers McInenly se départissent du reste du domaine en le divisant en lots à bâtir. Des ouvriers du chemin du Foulon montent alors sur le plateau avec leurs familles et s’établissent tout près de leur église et de leur école. Le docteur Arthur Lavoie élit domicile dans la Côte de l’Église, un magasin général ouvre ses portes, une banque, un bureau de poste… On assiste à la naissance du quartier ouvrier de la Côte de l’Église connu aujourd’hui comme le faubourg Saint- Michel. À l’est de la côte, au sud du cimetière jardin Mount Hermon (1848), le faubourg s’étend jusqu’à la falaise. -

United Way of Greater Milwaukee & Waukesha County Hosts

For Immediate Release For more information, contact Rebecca Schimke, Communications Specialist [email protected] 414.263.8125 (O), 414.704.8879 (C) United Way of Greater Milwaukee & Waukesha County Hosts Children’s Writer & Illustrator of Arthur Adventure Series, Marc Brown, to Promote Childhood Literacy Reading Blitz Day also celebrated Reader, Tutor, Mentor Volunteers. MILWAUKEE [March 25, 2015] – United Way of Greater Milwaukee & Waukesha County hosted a Reading Blitz Day to celebrate a 3-year effort of recruiting and placing 4,800+ reader, tutor, and mentor volunteers throughout Greater Milwaukee. The importance of reading to kids cannot be overstated. “Once children start school, difficulty with reading contributes to school failure, which can increase the risk of absenteeism, leaving school, juvenile delinquency, substance abuse, and teenage pregnancy - all of which can perpetuate the cycles of poverty and dependency.” according to the non-profit organization, Reach Out & Read. “United Way recognizes that caring adults working with children of all ages has the power to boost academic achievement and set them on the track for success,” said Karissa Gretebeck, marketing and community engagement specialist, United Way of Greater Milwaukee & Waukesha County. “We are thankful for the agency partners, other non-profits and schools who partnered with us to make this possible.” United Way also organized a book drive leading up to the day. New or gently used books were collected at 13 Milwaukee Public Library locations, Brookfield Public Library, Muskego Public Library and Martha Merrell’s Books in downtown Waukesha. Books from the drive will be donated to United Way funded partner agencies that were a part of the Reader, Tutor, Mentor effort. -

ARTHUR Elevation K Presidential Series

ARTHUR Elevation K Presidential Series Optional Carolina with Partial Brick Front Optional Partial Brick Front Optional Partial Brick Front Optional Siding Front ARTHUR Elevation K Presidential Series FIRST FLOOR SECOND FLOOR DUKE BATH OPT. FIREPLACE OPT. TRAY CEILING LIN BEDROOM 4 OPT. 11'5 X 15'7 BREAKFAST DOORS DUKE PANTRY NOOK BATH 11'0 X 6'10 W.I.C. LIN BEDROOM 4 OPT. 11'5 X 15'7 SINGLE OR DOUBLE MASTER BEDROOM 2 MASTER DOOR BATH GREAT W.I.C. 12'1 X 13'5 W.I.C. BEDROOM 17'1 X 20'3 ROOM FLEX 22'3 X 18'3 SUNROOM SPACE 2 OPT. BEDROOM 4 W/DUKE BATH 11'8 X 21'5 15'5 X 9'8 OPEN ILO OPEN TO BELOW DW FIREPLACE OPT. BEDROOM 5 TO 11'7 X 13'7 BELOW OPT. BEDROOM 4 W/DUKE BATH OPT. OPT. W D REF ILO OPEN TO BELOW OPT. OPT. DOUBLE KITCHEN DOORS DOORS 13'4 X 16'9 BATH LAUNDRY UP 2 DN PANTRY 36"36" HIGH HIGH WALL WALL PWDR LINEN OPT. SUNROOM LINEN OPT. BEDROOM36" 5 HIGH ILO WALL LOFT OPT. COATS OPT. 3 CAR GARAGE 27'4 X 19'5 LOFT BEDROOM 3 BEDROOM11'7 X 12'7 5 OPEN 13'2 X 12'7 TO FOYER 11'7 X 12'5 BELOW FLEX BEDROOM 4 SPACE 1 LOFT 11'5 X 13'2 13'8 X 11'8 11'7 X 12'7 BEDROOM 3 STEP BEDROOM 3 PORCH BATH OPT. DOORS BENCH OPT. LOFT ILO BEDROOM 5 FIRST FLOOR OPT. -

Port Arthur Geology

PORT ARTHUR, TEXAS/LOUISIANA 30 x 60 MINUTE GEOLOGIC QUADRANGLE SERIES 94°00' 45' 30°00' 30' 93°00' u 15' u o Hsm yo u a y B yo a k Ppbe Ppbe 30°00' a B ac Pper G B r Bl Pper Hcm D r e a Description of Map Units Neches ig iv U Hackberry D n Pper Ppbe N d R Ppbe Pper Pper Ppbe d l Old River Cove O Sabine Hcm Canal Rycade Vincent Island U Hm Ppbe Island Ppbe s Pper Canal Ppbe River s Jubert a Hm L Pper P Point a k t Ppbe Hua e HOLOCENE Humble as Sweet Lake E Black Bayou Pper Ppbe Atreco Island s R e Grays i s s Ppbe d Holocene undifferentiated alluvium—undifferentiated deposits of small upland Port Neches k ou s u r Bay g a a Pper l o t e Willow Lake INTRACOASTAL WATERWAY Prong S U Hua o y Hua streams: alluvial deposits of minor streams and creeks, of varying textures, filling valleys a M Ppbe D B Ppbe Canal North incised into older deposits. Ditch Commissary Point Hm Ppbe Pirogue Hm Pper Small river meander-belt deposits—point-bar and associated overbank deposits ORANGE CO Starks North Canal JEFFERSON CO Starks North u East Ppbe No 1 Canal INTRACOASTAL Hsm underlying meander belts of the Sabine River. These deposits typically consist of gray to o y Fork a reddish brown sand, silt, silty clay, and sandy clay. Canal B U D L A No 2 Canal Ppbe Mermentau Alloformation—Complexly interfingering and interbedded, dark-colored N A s n Wild Cow Savane Neuville Island C Hm marine muds, sandy and shelly beach deposits, organic marsh clays, and lacustrine and e Right re Lake G bay muds.