Our World Is Burning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Capitalism and Planetary Destruction: Activism for Climate Change Emergency

!"#$"%&#'()*+,-'.&%/+0$'123)%4'5'6%&,$+,3! "#$%&'!()!*(+(+,-!../!01(2' ! 78+$)%90':)$3!!34'!56789$'!8:!5!:$8;47$<!5&'=>'>!?'6:8#=!#@!A45.7'6!0!*../!001BC,!#@!74'!5%74#6D:! E##F-!!#+;&$3'!2&:*3<'$23'=)"%$2'>:8"0$%+&#'?3@)#"$+):'&:8'6"A#+,'638&*)*+30-'123'!&03'B)%' 7,)0),+&#+0;-!7#!E'!.%E$8:4'>!E<!G#%7$'>;'!8=!(+(0/! ! "#$%&#'%()!#*+!,'#*-&#./!0-(&.12&%3*4!52&%6%()!73.!"'%)#&-!"8#*9-! :)-.9-*2/! H8F'!A#$'! C:+@3%0+$4')B'7&0$'():8):! "#$%&'()$*&#+ 348:! 56789$'! 8:! 8=! 7I#! :'978#=:/! J=! :'978#=! 0-! J! >8:9%::! 74'! 6'$578#=:48.! E'7I''=! 95.875$8:&! 5=>! .$5='756<!>':76%978#=-!5=>!8=!:'978#=!(-!5978?8:&!@#6!9$8&57'!945=;'!'&'6;'=9</!J!E';8=!:'978#=!0! I874! 5! E68'@! :%&&56<! #@! 74'! 5;6''&'=7! &5>'! 57! 74'! (+0C! K=87'>! L578#=:! A$8&57'! A45=;'! A#=@'6'=9'!8=!M568:/!J!74'=!9#=:8>'6!74'!6'$578#=:48.!E'7I''=!95.875$8:&!5=>!.$5='756<!>':76%978#=-! @#9%:8=;! #=! 74'! =';578?'! 6#$'! #@! 9'6758=! 95.875$8:7! I#6$>! $'5>'6:-! =5&'$<! N#=5$>! 36%&.-! O586! P#$:#=56#! 5=>! Q9#77! H#668:#=/! L'R7! J! 5>>6'::! 74'! M568:! 9$8&57'! 945=;'! 599#6>! @#%6! <'56:! #=S! H5>68>!*ATM!(C,-!:%;;':78=;!7457!I'!&5<!E'!#=!5!76'=>!@#6!7#75$!.$5='756<!9575:76#.4'/!J!9#=9$%>'! :'978#=!0!I874!5!@#6I56>!$##F!7#!U$5:;#I!(+(0!*ATM!(V,-!:%;;':78=;!7457!I'!45?'!5!&#%=758=!7#! 9$8&E/!J=!:'978#=!(-!5@7'6!E68'@$<!#%7$8=8=;!74'!$#=;!48:7#6<!#@!9$8&57'!945=;'!5I56'='::-!74'!6#$'! #@!5978?8:&!8=!@#:7'68=;!9$8&57'!945=;'!'&'6;'=9<!8:!5=5$<:'>-!I874!6'@'6'=9'!7#!U6'75!34%=E'6;-! 5=>!&#?'&'=7:!8=:.86'>!E<!4'6!'R5&.$'-!5:!I'$$!5:!WR78=978#=!G'E'$$8#=/!34'!95:'!8:!&5>'!7457!5! -

January 2021

DOMESTIC ENERGY PRODUCERS ALLIANCE January 2021 DEPA REPORT ON INDUSTRY, LEADERSHIP, LEGISLATION AND ENERGY REGULATION Where We Are and What Now Written by David Crane, DEPA DC Lobbyist or the past year we have been discussing the possibil- which initiates a series of regulatory actions to combat ity and implications of change in Washington. On January climate change domestically and elevates climate change 20th those discussions became reality as Joe Biden was as a national security priority, issuance of a Scientific In- sworn-in as the 46th President of the United States. Presi- tegrity Presidential Memorandum which “directs science dent Biden has the added benefit and evidence based decision-making of Democrat control in both the in federal agencies”, issuance of an House and Senate as the Demo- Executive Order re-establishing the crats swept both seats in the Geor- Presidential Council of Advisors on gia Senate run-off. As a result of Science and Technology and announc- a 50-50 tie Vice President Harris ing the data for U.S.-hosted Climate casts the deciding vote making Leaders’ Summit to be held on April Chuck Schumer the Senate Major- 22. ity leader. Beyond the usual line-up of energy Out of the blocks the Biden regulators the Biden Administration is Administration made clear there opening a new front aimed at limiting would be a radical shift in ap- and denying access to capital by those proach to domestic energy pro- “DEPA will be running engaged in domestic energy produc- duction. On day one of his presi- hard to bring the facts to tion. -

EC.719 D-Lab: Water, Climate, and Health, Lec 2

Water, Climate Change and Health Photo: Apollo 8 image of "Earthrise” by William Anders, AS8-14-2383, Dec. 24, 1968 .iiniin. Susan Murcott, Week 2 --D-Lab: Water, Climate Change and Health 1 4 Challenging Questions (add answers on index card) 1. Define “life.” 2. Complete this sentence: “Planet Earth is ill because…” 3. What makes a planet habitable? 4. In honor of Valentines Day: complete this sentence: “Love [in relation to Water, Climate Change and Health] is…” 2 Outline • Human Health, Planetary Health, Planetary Boundaries • Comparing Venus, Earth and Mars • What Makes a Planet Habitable? • Inside Story of Paris Agreement • Solutions (Maslin, Ch 8) & Terminology • Adaptation • Mitigation • Geoengineering • Solar Radiation Management 3 Human Body Temperature • For a typical adult: 97 F to 99 F. • Infants and children: 97.9 F to 100.4 F. • A body temperature higher than your normal range is a fever. • Hypothermia is when the body temperature dips too low. • Either extreme is a medical emergency © source unknown. All rights reserved. This content is excluded from our Creative Commons license. For more information, see https://ocw.mit.edu/help/faq-fair-use/ 4 Human Health – Example of a healthy individual, with each of the parameters falling within an standard average range Comprehensive Metabolic Panel – Details Feb. 4, 2019 5 Is the Earth a living planet? Is it ill? • In many ways, climate change for Earth can be seen in the same way as illness and the human body. Mark Maslin, Climate Change p 162. I have asked that you take on for discussion that the Earth is in some sense alive and that the diagnosis and treatment of its ills become an empirical practice…The notion of the planet visiting a doctor is odd. -

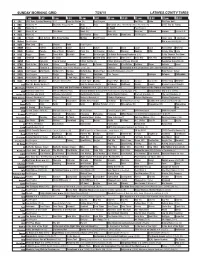

Sunday Morning Grid 7/26/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 7/26/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Golf Res. Faldo PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Volleyball 2015 FIVB World Grand Prix, Final. (N) 2015 Tour de France 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Outback Explore Eye on L.A. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Hour Mike Webb Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program Rio ››› (2011) (G) 18 KSCI Man Land Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Contac Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dowdle Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking BBQ Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight Ed Slott’s Retirement Roadmap (TVG) Celtic Thunder The Show 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Cinderella Man ››› 34 KMEX Paid Conexión Tras la Verdad Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Hour of In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Gran Premio Hungria 2015. -

Robbie Pettigrew Editor Avid, Premiere

Agent: Bhavinee Mistry [email protected] 020 7199 3852 Robbie Pettigrew Editor Avid, Premiere Documentary Dr. Jeff Rocky Mountain Vet, Series 4, 5, 6, 7 & Specials Double Act TV Animal Planet 7 x 60 min Documentary Dr Jeff, an unconventional vet, and his staff treat a wide variety of animals in his Denver practice. Gold Rush: Dave Turin’s Lost Mines Raw TV Discovery 60 min Documentary Gold miner Dave Turin, previously featured in Gold Rush, visits 8 disused gold mines around the Western United States and decides which mine to get up and running to turn it into a profitable, working mine. Welcome to HMP Belmarsh with Ross Kemp Multistory Media ITV 60 min Documentary Ross Kemp goes inside the walls of HMP Belmarsh, the country's most notorious maximum security jail, that has housed the country's most dangerous and infamous convicts. Valley of the Damned October Films Investigation 2 x 60 min Documentary Discovery This series examines a collection of deceitful murders all taking place in the beautiful, yet desolate, mountain region known as ‘Prison Valley’ in the Colorado Rockies - home to a cast of intriguing characters who all have secrets, and nobody can be trusted. Gold Rush: Parkers Trail Raw TV Discovery 60 min Documentary Having tackled the rugged and dangerous trails of the Klondike and the hostile jungles of Guyana, Parker Schnabel is ready to take his hunt for gold to the next level, in Papua New Guinea. Homestead Rescue Raw TV Discovery 60 min Documentary Struggling homesteaders across the US are turning to expert homesteader Marty Raney – along with his daughter Misty Raney, a farmer, and son Matt Raney, a hunter and fisherman – to teach them the necessary skills to survive the wilderness. -

Vanuatu) John Frum Superstar: Images of the Cargo Cult in Tanna (Vanuatu)

Journal de la Société des Océanistes 148 | 2019 Filmer (dans) le Pacifique John Frum Superstar : images du culte du cargo à Tanna (Vanuatu) John Frum Superstar: images of the cargo cult in Tanna (Vanuatu) Marc Tabani Édition électronique URL : https://journals.openedition.org/jso/10210 DOI : 10.4000/jso.10210 ISSN : 1760-7256 Éditeur Société des océanistes Édition imprimée Date de publication : 15 juillet 2019 Pagination : 113-125 ISBN : 978-2-85430-137-3 ISSN : 0300-953x Référence électronique Marc Tabani, « John Frum Superstar : images du culte du cargo à Tanna (Vanuatu) », Journal de la Société des Océanistes [En ligne], 148 | 2019, mis en ligne le 01 janvier 2021, consulté le 22 juillet 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/jso/10210 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/jso.10210 Journal de la société des océanistes est mis à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. John Frum Superstar : images du culte du cargo à Tanna (Vanuatu) par Marc TABANI* RÉSUMÉ ABSTRACT L’île de Tanna a attiré plusieurs générations de réalisateurs The island of Tanna has attracted successive generations de films. La plupart ont été immanquablement fascinés par of filmmakers. Most of them have been invariably fasci- l’histoire de John Frum, un personnage surnaturel dont les nated by the story of John Frum, a supernatural figure prophéties ont donné naissance, au cours de la Seconde Guerre whose prophecies gave rise during World War Two to a mondiale, à un vaste mouvement indigène de protestation huge indigenous movement of social protest. -

Our Faustian Bargain

Our Faustian Bargain J. Edward Anderson, PhD, Retired P.E.1 1 Seventy years Engineering Experience, M.I.T. PhD, Aeronautical Research Scientist NACA, Principal Research Engineer Honeywell, Professor of Mechanical Engineering, 23 yrs. University of Minnesota, 8 yrs. Boston University, Fellow AAAS, Life Member ASME. You can make as many copies of this document as you wish. 1 Intentionally blank. 2 Have We Unwittingly made a Faustian Bargain? This is an account of events that have led to our ever-growing climate crisis. Young people wonder if they have a future. How is it that climate scientists discuss such an outcome of advancements in technology and the comforts associated with them? This is about the consequences of the use of coal, oil, and gas for fuel as well as about the science that has enlightened us. These fuels drive heat engines that provide motive power and electricity to run our civilization, which has thus far been to the benefit of all of us. Is there a cost looming ahead? If so, how might we avoid that cost? I start with Sir Isaac Newton (1642-1727).2 In the 1660’s he discov- ered three laws of motion plus the law of gravitation, which required the concept of action at a distance, a concept that scientists of his day reacted to with horror. Yet without that strange action at a distance we would have no way to explain the motion of planets. The main law is Force = Mass × Acceleration. This is a differential equation that must be integrated twice to obtain position. -

Our Faustian Bargain

Our Faustian Bargain J. Edward Anderson, PhD, Retired P.E.1 1 Seventy years Engineering Experience, M.I.T. PhD in Aeronautics & Astronautics, Aeronautical Research Scientist NACA, Principal Research Engineer Honeywell, Professor of Mechanical Engineering, 23 yrs. University of Minnesota, 8 yrs. Boston University, Fellow AAAS, Life Member ASME. You may distribute as many copies of this document as you wish. 1 Intentionally blank. 2 Have We Unwittingly made a Faustian Bargain? This is an account of events that have led to our ever-growing climate crisis. Young people wonder if they have a future. How is it that climate scientists discuss such an outcome of advancements in technology and the comforts associated with them? This is about the consequences of the use of coal, oil, and gas for fuel as well as about the science that has enlightened us. These fuels drive heat engines that provide motive power and electricity to run our civilization, which has thus far been to the benefit of all of us. Is there a cost looming ahead? If so, how might we avoid that cost? I start with Sir Isaac Newton (1642-1727).2 In the 1660’s he discovered three laws of motion plus the law of gravitation, which requires the con- cept of action at a distance, a concept that scientists of his day reacted to with horror. Yet without that strange action at a distance there would be no way to explain the motion of planets. The main law is Force = Mass × Acceleration. This is a differential equation that must be integrated twice to obtain position. -

RUSSIAN WORLD VISION Russian Content Distributor Russian World Vision Signed an Inter- National Distribution Deal with Russian Film Company Enjoy Movies

CISCONTENT:CONTENTRREPORTEPORT C ReviewОбзор of новостейaudiovisual рынка content производства production and и дистрибуции distribution аудиовизуальногоin the CIS countries контента Media«»«МЕДИ ResourcesА РЕСУРСЫ МManagementЕНЕДЖМЕНТ» №11№ 1(9) February №213 января, 1 April, 22, 20132011 2012 тема FOCUSномера DEARслово COLLEAGUES редакции WeУже are в happyпервые to presentдни нового you the года February нам, issue редак ofц theии greatПервый joy itномер appeared Content that stillReport there выходит are directors в кану whoн КИНОТЕАТРАЛЬНЫ Й CISContent Content Report, Report сразу where стало we triedпонятно, to gather что в the 2011 mostм treatСтарого film industryНового as года, an art который rather than (наконецто) a business за все мы будем усердно и неустанно трудиться. За вершает череду праздников, поэтому еще раз РЫНTVО КMARKETS В УКРАИН Е : interesting up-to-date information about rapidly de- velopingнимаясь contentподготовкой production первого and выпуска distribution обзора markets но хотим пожелать нашим подписчикам в 2011 ЦИФРОВИЗАЦИ Я КА К востей рынка производства и аудиовизуального годуAnd one найти more свой thing верный we’d likeпуть to и remindследовать you. емуPlan с- IN TAJIKISTAN, of the CIS region. As far as most of the locally pro- ning you business calendar for 2013 do not forget to ducedконтента series в этом and год TVу ,movies мы с радостью are further обнаружили distributed, упорством, трудясь не покладая рук. У каждого UZBEKISTAN,ОСНОВНОЙ ТРЕН ANDД что даже в новогодние праздники работа во мно свояbook timeдорога, to visit но theцель major у нас event одн forа – televisionразвивать and и and broadcast mainly inside the CIS territories, we media professionals in the CIS region - KIEV MEDIA РАЗВИТИ Я (25) pickedгих продакшнах up the most идет interesting полным хо andдом, original а дальше, projects как улучшать отечественный рынок. -

Inclusion of Frontline Communities in the Sunrise Movement Senior Honors Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the School of Arts

Inclusion of Frontline Communities in the Sunrise Movement Senior Honors Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Undergraduate Program in Environmental Studies Professor Brian Donahue, Advisor In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts by Phoebe Dolan April 2020 Copyright by Phoebe Dolan Committee Members Professor Brian Donahue Professor Sabine Von Mering Professor Gowri ViJayakumar Abstract Environmental activism and climate activism have a long history in the United States. Historically the membership of the environmental movement was white, old, educated and mostly male. This history led to the exclusion of communities of color, low income communities and indigenous communities from the mainstream climate movement. The Sunrise Movement is a youth climate movement, founded in 2017, fighting for the futures of young people in the face of the climate crisis. Sunrise has the unique angle of representing youth as a frontline to the future of the climate crisis, but as a movement how are they uplifting other frontline communities such as people of color, low income communities, island populations and beyond? How does the Sunrise Movement uplift and center frontline communities in their organizations, what are their tactics, where are they challenged and how are they succeeding? I interviewed 11 current leaders within the Sunrise movement and asked them if Sunrise succeeded at uplifting and centering frontline communities and where they were challenged. Common themes came up for many participants, Sunrise embraces storytelling as a form of narrative around climate justice, but they tend to tokenize frontline voices. Urgency is necessary for the Sunrise Movement to act on the climate crisis, but Sunrise must curb their speed in order to focus on inclusion as a movement goal. -

'John Frum Files' (Tanna, Vanuatu, 1941–1980)

Archiving a Prophecy. An ethnographic history of the ‘John Frum files’ (Tanna, Vanuatu, 1941–1980) Marc Tabani To cite this version: Marc Tabani. Archiving a Prophecy. An ethnographic history of the ‘John Frum files’ (Tanna, Vanuatu, 1941–1980). PAIDEUMA. Mitteilungen zur Kulturkunde, Frobenius Institute, 2018, 64. hal-01962249 HAL Id: hal-01962249 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01962249 Submitted on 9 Jul 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - ShareAlike| 4.0 International License Paideuma 64:99-124 (2018) ARCHIVING A PROPHECY An ethnographie history of the 'John Frum files' (Tanna, Vanuatu, 1941-1980) MarcTabani ABSTRACT. Repeated signs of a large-scale rebellion on the South Pacifie island of Tanna (Va nuatu) appeared in 1941. Civil disobedience was expressed through reference to a prophetic fig ure namedJohn Frum. In order to repress this politico-religious movement, categorized later as a cargo cult in the anthropological literature, the British administration accumulated thousands of pages of surveillance notes, reports and commentaries. This article proposes an introduction to the existence of these documents known as the 'John Frum files', which were classified as confidential until the last few years. -

Triumph Debate Lincoln Douglas Brief – November/December 2020

N O VEM B ER/ D ECEM B ER: RESO LV ED : T H E U N I TED ST A T ES O U GH T TO PRO V I D E A FED ERA L JO BS GU A RAN T EE. 0 TRIUMPH DEBATE LINCOLN DOUGLAS BRIEF – NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2020 1 TRIUMPH DEBATE LINCOLN DOUGLAS BRIEF – NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2020 Table of Contents TOPIC ANALYSIS – BY MATT SLENCSAK ........................................................................................................................................ 6 FRAMING ................................................................................................................................................................................. 14 PHILOSOPHICAL AND ECONOMIC JUSTIFICATIONS REQUIRED TO SUPPORT JOBS GUARANTEE ................................................................ 14 THE JOBS GUARANTEE IS BASED ON A FLAWED CONCEPTION OF RIGHTS ................................................................................................ 15 THE RIGHT TO A JOB IS A BASIC HUMAN RIGHT ....................................................................................................................................... 16 HEGEL MARKET EXPLANATION ................................................................................................................................................................ 17 HEGEL ON WELFARE AND CORPORATISM ............................................................................................................................................... 17 HEGEL - JOBS GUARANTEE ....................................................................................................................................................................