'A Total Work of Architectural and Landscape Art' a Vision For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shaping the Future of Professional Life

westminster.ac.uk SHAPING THE FUTURE OF PROFESSIONAL LIFE A charity and a company limited by guarantee. Registration number: 977818. Registered office: 309 Regent Street, London W1B 2UW 6466/10.13/KR/BP 309 Regent Street in 1909 and now (opposite) FOREWORD INTRODUCTION The University of Westminster’s 175th The University’s central London More than anything, this book This year marks a special milestone In the intervening years our This brochure highlights the strength anniversary is a significant milestone. location has played its part, giving underlines the continuing importance in the history of the University of institution has advanced and of the relationships between our The history of the Royal Institute of students access to outstanding that the University of Westminster Westminster, as we celebrate the expanded – significantly under the institution and the professional bodies British Architects – RIBA – spans a resources, to powerful professional places on building strong partnerships 175th anniversary of the opening leadership of Quintin Hogg (1881– in London, across the UK and very similar timescale; we celebrated networks, and fantastic career with professional practice, to help of The Polytechnic Institution, the 1903) as the Regent Street Polytechnic, internationally. Those relationships, our 175th anniversary in 2009, and opportunities upon graduation. achieve its mission of ‘building the forerunner of our University, at then as the Polytechnic of Central born in the eras of Cayley and Hogg, since the opening of the School of But Westminster’s reach goes far next generation of highly employable 309 Regent Street. The Institution London (formed in 1970) and, were clearly nurtured throughout the Architecture at the Regent Street beyond the country’s capital. -

St Marylebone Parish Church Records of Burials in the Crypt 1817-1853

Record of Bodies Interred in the Crypt of St Marylebone Parish Church 1817-1853 This list of 863 names has been collated from the merger of two paper documents held in the parish office of St Marylebone Church in July 2011. The large vaulted crypt beneath St Marylebone Church was used as place of burial from 1817, the year the church was consecrated, until it was full in 1853, when the entrance to the crypt was bricked up. The first, most comprehensive document is a handwritten list of names, addresses, date of interment, ages and vault numbers, thought to be written in the latter half of the 20th century. This was copied from an earlier, original document, which is now held by London Metropolitan Archives and copies on microfilm at London Metropolitan and Westminster Archives. The second document is a typed list from undertakers Farebrother Funeral Services who removed the coffins from the crypt in 1980 and took them for reburial at Brookwood cemetery, Woking in Surrey. This list provides information taken from details on the coffin and states the name, date of death and age. Many of the coffins were unidentifiable and marked “unknown”. On others the date of death was illegible and only the year has been recorded. Brookwood cemetery records indicate that the reburials took place on 22nd October 1982. There is now a memorial stone to mark the area. Whilst merging the documents as much information as possible from both lists has been recorded. Additional information from the Farebrother Funeral Service lists, not on the original list, including date of death has been recorded in italics under date of interment. -

Picturesque Architecture 2Nd Term 1956 (B3.6)

Picturesque Architecture 2nd Term 1956 (B3.6) In a number of lectures given during the term Professor Burke has shown how during the 18th century, in both the decorative treatment of interiors and in landscape gardening, the principle of symmetry gradually gave way to asymmetry; and regularity to irregularity. This morning I want to show how architecture itself was affected by this new desire for irregularity. It is quite an important point. How important we can see by throwing our thoughts back briefly for a moment over the architectural past we have traced during the year. The Egyptian temple, the Mesopotamian temple, the Greek temple, the Byzantine church, the Gothic church, the Renaissance church, the Baroque church, the rococo country house and the neo- classical palace were all governed by the principle of symmetry. However irregular the Gothic itself became by virtue of its piecemeal building processes, or however wild the Baroque and the Rococo became in their architectural embellishments, they never failed to balance one side of the building with the other side, about a central axis. Let us turn for a moment to our time. Symmetry is certainly not, as we see in out next slide, an overriding rule of contemporary planning. If a symmetrical plan is chosen by an architect today, it is the result of a deliberate choice, chosen for being most suited for the circumstances, and not, as it was in the past, an accepted architectural presupposition dating back to the very beginnings of architecture itself. Today plans are far more often asymmetrical than symmetrical. -

Transport with So Many Ways to Get to and Around London, Doing Business Here Has Never Been Easier

Transport With so many ways to get to and around London, doing business here has never been easier First Capital Connect runs up to four trains an hour to Blackfriars/London Bridge. Fares from £8.90 single; journey time 35 mins. firstcapitalconnect.co.uk To London by coach There is an hourly coach service to Victoria Coach Station run by National Express Airport. Fares from £7.30 single; journey time 1 hour 20 mins. nationalexpress.com London Heathrow Airport T: +44 (0)844 335 1801 baa.com To London by Tube The Piccadilly line connects all five terminals with central London. Fares from £4 single (from £2.20 with an Oyster card); journey time about an hour. tfl.gov.uk/tube To London by rail The Heathrow Express runs four non- Greater London & airport locations stop trains an hour to and from London Paddington station. Fares from £16.50 single; journey time 15-20 mins. Transport for London (TfL) Travelcards are not valid This section details the various types Getting here on this service. of transport available in London, providing heathrowexpress.com information on how to get to the city On arrival from the airports, and how to get around Heathrow Connect runs between once in town. There are also listings for London City Airport Heathrow and Paddington via five stations transport companies, whether travelling T: +44 (0)20 7646 0088 in west London. Fares from £7.40 single. by road, rail, river, or even by bike or on londoncityairport.com Trains run every 30 mins; journey time foot. See the Transport & Sightseeing around 25 mins. -

The Industrial Revolution: 18-19Th C

The Industrial Revolution: 18-19th c. Displaced from their farms by technological developments, the industrial laborers - many of them women and children – suffered miserable living and working conditions. Romanticism: late 18th c. - mid. 19th c. During the Industrial Revolution an intellectual and artistic hostility towards the new industrialization developed. This was known as the Romantic movement. The movement stressed the importance of nature in art and language, in contrast to machines and factories. • Interest in folk culture, national and ethnic cultural origins, and the medieval era; and a predilection for the exotic, the remote and the mysterious. CASPAR DAVID FRIEDRICH Abbey in the Oak Forest, 1810. The English Landscape Garden Henry Flitcroft and Henry Hoare. The Park at Stourhead. 1743-1765. Wiltshire, England William Kent. Chiswick House Garden. 1724-9 The architectural set- pieces, each in a Picturesque location, include a Temple of Apollo, a Temple of Flora, a Pantheon, and a Palladian bridge. André Le Nôtre. The gardens of Versailles. 1661-1785 Henry Flitcroft and Henry Hoare. The Park at Stourhead. 1743-1765. Wiltshire, England CASPAR DAVID FRIEDRICH, Abbey in the Oak Forest, 1810. Gothic Revival Architectural movement most commonly associated with Romanticism. It drew its inspiration from medieval architecture and competed with the Neoclassical revival TURNER, The Chancel and Crossing of Tintern Abbey. 1794. Horace Walpole by Joshua Reynolds, 1756 Horace Walpole (1717-97), English politician, writer, architectural innovator and collector. In 1747 he bought a small villa that he transformed into a pseudo-Gothic showplace called Strawberry Hill; it was the inspiration for the Gothic Revival in English domestic architecture. -

The London Diplomatic List

UNCLASSIFIED THE LONDON DIPLOMATIC LIST Alphabetical list of the representatives of Foreign States & Commonwealth Countries in London with the names & designations of the persons returned as composing their Diplomatic Staff. Representatives of Foreign States & Commonwealth Countries & their Diplomatic Staff enjoy privileges & immunities under the Diplomatic Privileges Act, 1964. Except where shown, private addresses are not available. m Married * Married but not accompanied by wife or husband AFGHANISTAN Embassy of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan 31 Princes Gate SW7 1QQ 020 7589 8891 Fax 020 7584 4801 [email protected] www.afghanistanembassy.org.uk Monday-Friday 09.00-16.00 Consular Section 020 7589 8892 Fax 020 7581 3452 [email protected] Monday-Friday 09.00-13.30 HIS EXCELLENCY DR MOHAMMAD DAUD YAAR m Ambassador Extraordinary & Plenipotentiary (since 07 August 2012) Mrs Sadia Yaar Mr Ahmad Zia Siamak m Counsellor Mr M Hanif Ahmadzai m Counsellor Mr Najibullah Mohajer m 1st Secretary Mr M. Daud Wedah m 1st Secretary Mrs Nazifa Haqpal m 2nd Secretary Miss Freshta Omer 2nd Secretary Mr Hanif Aman 3rd Secretary Mrs Wahida Raoufi m 3rd Secretary Mr Yasir Qanooni 3rd Secretary Mr Ahmad Jawaid m Commercial Attaché Mr Nezamuddin Marzee m Acting Military Attaché ALBANIA Embassy of the Republic of Albania 33 St George’s Drive SW1V 4DG 020 7828 8897 Fax 020 7828 8869 [email protected] www.albanianembassy.co.uk HIS EXELLENCY MR MAL BERISHA m Ambassador Extraordinary & Plenipotentiary (since 18 March 2013) Mrs Donika Berisha UNCLASSIFIED S:\Protocol\DMIOU\UNIVERSAL\Administration\Lists of Diplomatic Representation\LDL\RESTORED LDL Master List - Please update this one!.doc UNCLASSIFIED Dr Teuta Starova m Minister-Counsellor Ms Entela Gjika Counsellor Mrs Gentjana Nino m 1st Secretary Dr Xhoana Papakostandini m 3rd Secretary Col. -

A Place for Music: John Nash, Regent Street and the Philharmonic Society of London Leanne Langley

A Place for Music: John Nash, Regent Street and the Philharmonic Society of London Leanne Langley On 6 February 1813 a bold and imaginative group of music professionals, thirty in number, established the Philharmonic Society of London. Many had competed directly against each other in the heady commercial environment of late eighteenth-century London – setting up orchestras, promoting concerts, performing and publishing music, selling instruments, teaching. Their avowed aim in the new century, radical enough, was to collaborate rather than compete, creating one select organization with an instrumental focus, self-governing and self- financed, that would put love of music above individual gain. Among their remarkable early rules were these: that low and high sectional positions be of equal rank in their orchestra and shared by rotation, that no Society member be paid for playing at the group’s concerts, that large musical works featuring a single soloist be forbidden at the concerts, and that the Soci- ety’s managers be democratically elected every year. Even the group’s chosen name stressed devotion to a harmonious body, coining an English usage – phil-harmonic – that would later mean simply ‘orchestra’ the world over. At the start it was agreed that the Society’s chief vehicle should be a single series of eight public instrumental concerts of the highest quality, mounted during the London season, February or March to June, each year. By cooperation among their fee-paying members, they hoped to achieve not only exciting performances but, crucially, artistic continuity and a steady momentum for fine music that had been impossible before, notably in the era of the high-profile Professional Concert of 1785-93 and rival Salomon-Haydn Concert of 1791-2, 1794 and Opera Concert of 1795. -

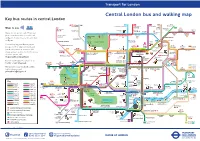

Central London Bus and Walking Map Key Bus Routes in Central London

General A3 Leaflet v2 23/07/2015 10:49 Page 1 Transport for London Central London bus and walking map Key bus routes in central London Stoke West 139 24 C2 390 43 Hampstead to Hampstead Heath to Parliament to Archway to Newington Ways to pay 23 Hill Fields Friern 73 Westbourne Barnet Newington Kentish Green Dalston Clapton Park Abbey Road Camden Lock Pond Market Town York Way Junction The Zoo Agar Grove Caledonian Buses do not accept cash. Please use Road Mildmay Hackney 38 Camden Park Central your contactless debit or credit card Ladbroke Grove ZSL Camden Town Road SainsburyÕs LordÕs Cricket London Ground Zoo Essex Road or Oyster. Contactless is the same fare Lisson Grove Albany Street for The Zoo Mornington 274 Islington Angel as Oyster. Ladbroke Grove Sherlock London Holmes RegentÕs Park Crescent Canal Museum Museum You can top up your Oyster pay as Westbourne Grove Madame St John KingÕs TussaudÕs Street Bethnal 8 to Bow you go credit or buy Travelcards and Euston Cross SadlerÕs Wells Old Street Church 205 Telecom Theatre Green bus & tram passes at around 4,000 Marylebone Tower 14 Charles Dickens Old Ford Paddington Museum shops across London. For the locations Great Warren Street 10 Barbican Shoreditch 453 74 Baker Street and and Euston Square St Pancras Portland International 59 Centre High Street of these, please visit Gloucester Place Street Edgware Road Moorgate 11 PollockÕs 188 TheobaldÕs 23 tfl.gov.uk/ticketstopfinder Toy Museum 159 Russell Road Marble Museum Goodge Street Square For live travel updates, follow us on Arch British -

Licensing Sub-Committee Report

Licensing Sub-Committee City of Westminster Report Item No: Date: 9 July 2020 Licensing Ref No: 20/02820/LIPN - New Premises Licence Title of Report: 94 Great Portland Street London W1W 7NU Report of: Director of Public Protection and Licensing Wards involved: West End Policy context: City of Westminster Statement of Licensing Policy Financial summary: None Report Author: Michelle Steward Senior Licensing Officer Contact details Telephone: 0207 641 6500 Email: [email protected] 1. Application 1-A Applicant and premises Application Type: New Premises Licence, Licensing Act 2003 Application received date: 10 March 2020 Applicant: Where The Pancakes Are Ltd Premises: Where The Pancakes Are Premises address: 94 Great Portland Street Ward: West End Ward London W1W 7NU Cumulative None Impact Area: Premises description: This is an application for a new premises licence to operate as a restaurant with an outside seating area and seeks permission for on and off sales for the sale by retail of alcohol. Premises licence history: As this is a new premises licence application, no premises licence history exists for this premises. Applicant submissions: The applicant has provided a brochure and biography of the company and branding which can be seen at Appendix 3 of this Report. 1-B Proposed licensable activities and hours Late Night Refreshment: Indoors, outdoors or both Both Day: Mon Tues Wed Thur Fri Sat Sun Start: 23:00 23:00 23:00 23:00 23:00 23:00 N/A End: 23:30 23:30 23:30 23:30 00:00 00:00 N/A Seasonal variations/ Non- Sunday before a Bank Holiday Monday: 23:00 hours standard timings: to 00:00 hours. -

'James and Decimus Burton's Regency New Town, 1827–37'

Elizabeth Nathaniels, ‘James and Decimus Burton’s Regency New Town, 1827–37’, The Georgian Group Journal, Vol. XX, 2012, pp. 151–170 TEXT © THE AUTHORS 2012 JAMES AND DECIMUS BURTON’S REGENCY NEW TOWN, ‒ ELIZABETH NATHANIELS During the th anniversary year of the birth of The land, which was part of the -acre Gensing James Burton ( – ) we can re-assess his work, Farm, was put up for sale by the trustees of the late not only as the leading master builder of late Georgian Charles Eversfield following the passing of a private and Regency London but also as the creator of an Act of Parliament which allowed them to grant entire new resort town on the Sussex coast, west of building leases. It included a favourite tourist site – Hastings. The focus of this article will be on Burton’s a valley with stream cutting through the cliff called role as planner of the remarkable townscape and Old Woman’s Tap. (Fig. ) At the bottom stood a landscape of St Leonards-on-Sea. How and why did large flat stone, locally named The Conqueror’s he build it and what role did his son, the acclaimed Table, said to have been where King William I had architect Decimus Burton, play in its creation? dined on the way to the Battle of Hastings. This valley was soon to become the central feature of the ames Burton, the great builder and developer of new town. The Conqueror’s table, however, was to Jlate Georgian London, is best known for his work be unceremoniously removed and replaced by James in the Bedford and Foundling estates, and for the Burton’s grand central St Leonards Hotel. -

![Transcription of 3D Royal Pavilion Estate Commentary [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1051/transcription-of-3d-royal-pavilion-estate-commentary-pdf-1001051.webp)

Transcription of 3D Royal Pavilion Estate Commentary [PDF]

Transcription of 3D and VR Pavilion Estate curatorial commentary Written and voiced by Alexandra Loske URL: http://brightonmuseums.org.uk/3DPavilion/ Royal Pavilion The Royal Pavilion was created between 1785 and 1823 by George, Prince of Wales who would later become Prince Regent and eventually King George IV. George first visited Brighton as a young man aged 21 in 1763 and soon after decided to make the seaside town his playground away from London. He rented a house on the site of the present Pavilion and in 1786 hired the architect Henry Holland to build him a ‘pavilion by the sea’. This first building on this site was a two-storey, symmetrical structure in a neo- classical style. It was elegant and sophisticated, but by no means exotic in appearance. George made alterations and changes to his pleasure palace throughout his life, gradually creating the outlandish and exuberant palace we see today -- although he never called it a palace. He mostly used it for lavish banquets and to stage great balls and concerts, and often spent several months at a time here. The greatest change to the exterior was made between 1815 and 1823, when the famous architect John Nash was hired to transform the neo-classical building into an oriental fantasy. The exterior we can see here was inspired by Indian architecture, with added Gothic elements. Nash added two large state rooms to the Pavilion on the north and south end, with tent-shaped roofs. The onion-shaped domes and ornamental features in the centre of the building were built around and on top of the existing building, using cast iron on a large scale. -

90 Harley Street London W1

90 HARLEY STREET LONDON W1 AN ATTRACTIVE GRADE II LISTED INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY ON ONE OF LONDON’S MOST FAMOUS WEST END STREETS 2. 3. “An attractive Grade II listed building arranged over lower ground, ground and four upper floors.” 90 HARLEY ST LONDON W1 4. 5. INVESTMENT SUMMARY • Harley Street is one of the West End’s most famous internationally recognised streets. • An attractive Grade II listed building arranged over lower ground, ground and four upper floors. • 999 year long leasehold interest at a fixed rent of £60 from Howard de Walden Estate. • Single let to dentists until 2026. • Rent review every 3 years with the next one being in September 2020. • Low base rent of £72.19 psf with prospects for rental growth. • Offers in excess of£6.32M subject to contract and exclusive of VAT. • Attractive net initial yield of 4%. • Potential to convert the whole to residential subject to the relevant planning consents. • Potential to create value by extending the leasehold interest of one of the flats which has 62 years unexpired. 90 HARLEY ST LONDON W1 6. 7. LOCATION REGENT’S PARK HARLEY REGENT’S PARK Harley Street is one of the West Ends most famous These developments provide a mix of office, retail and STREET LONDON W1 internationally recognised streets. The properties in this area residential accommodation with the local appeal of shops in 90 date back to the 18th Century when the area was developed Oxford Street, Regent Street and all the facilities the West End by Cavendish – Harley Family. Today properties in Harley has to offer.