Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae Yu-Jui Yvonne Wan, Phd Professor and Vice Chair of Research Department of Medical Pathology & Laboratory Medicine University of California, Davis

Curriculum Vitae Yu-Jui Yvonne Wan, PhD Professor and Vice Chair of Research Department of Medical Pathology & Laboratory Medicine University of California, Davis Contact Information: Department of Medical Pathology & Laboratory Medicine University of California Davis Health 4645 2nd Avenue, Research III, Room 3400B Sacramento, CA 95817 Office: (916) 734-4293 E-mail: [email protected] Education: 1981 - 1983 Ph.D. Experimental Pathology, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA 1979 - 1981 M.S. Experimental Pathology, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA 1975 - 1979 B.S. Taipei Medical University, School of Pharmacy, Taipei, Taiwan Professional Experience: 2012 - Present Professor and Vice Chair of Research, Department of Medical Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, University of California, Davis Health System 2012 - 2017 Scientific Director of Biorepository, University of California, Davis Health System 2012 - 2015 Visiting Professor, Institute of Chinese Meteria Medica, Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shanghai, China 2009 - Present Visiting Professor, Guangzhou Medical College, Guangzhou, China 2007 - 2012 Director, Liver Center, University of Kansas Medical Center (KUMC), KS 2007 - 2012 Leader, Cancer Biology Program, the University of Kansas Cancer Center, KS 2007 - 2010 Joy McCann Professor, KUMC 2006 - 2009 Adjunct Professor, Department of Pathology, KUMC 2003 - 2012 Professor, Department of Pharmacology, Toxicology & Therapeutics, KUMC 2002 - Present Visiting Professor, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan 2001 -

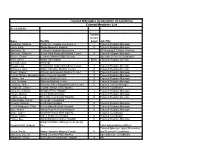

Californiachoice® Small Group Advantage PPO Three-Tier Hospital Network

CaliforniaChoice® Small Group Advantage PPO three-tier hospital network With the CaliforniaChoice Advantage PPO plans, you have a choice of tiers (or levels) of hospitals to visit. Tier one hospitals offer the greatest savings to you. Tier two hospitals have the second best level of savings. Tier three hospitals — or out-of-network hospitals — offer the least out-of-pocket savings, but you’ll still be covered. Keep in mind that the tier levels aren’t based on the quality of care given at each hospital. They’re based on which hospitals have shown they’re better able to give quality care that’s also cost effective. Our three-tier levels* are: }}Tier 1 — PPO network hospitals with lower-negotiated hospital reimbursement rates. }}Tier 2 — the remaining PPO network hospitals. }}Tier 3 — non-network hospitals. * The tier levels are not based on the quality of care given at each hospital. Instead, each level stands for the hospitals that show 19685CABENABC 08/15 the best use of health care dollars. CaliforniaChoice® Small Group Advantage PPO three-tier hospital network Here is a list of the Tier-1 and Tier-2 hospitals included in the network. Any hospital not listed is considered out of network. Hospital County Tier St Rose Hospital Alameda 1 Alameda Hospital Alameda 1 Children’s Hospital Oakland Alameda 2 Valleycare Medical Center Alameda 2 Washington Hospital Alameda 2 Sutter Amador Health Center Pioneer 1 Sutter Amador Health Center Plymouth 1 Sutter Amador Hospital Amador 1 Oroville Hospital & Medical Center Butte 1 Feather River Hospital -

Access+ HMO 2021Network

Access+ HMO 2021Network Our Access+ HMO plan provides both comprehensive coverage and access to a high-quality network of more than 10,000 primary care physicians (PCPs), 270 hospitals, and 34,000 specialists. You have zero or low copayments for most covered services, plus no deductible for hospitalization or preventive care and virtually no claims forms. Participating Physician Groups Hospitals Butte County Butte County BSC Admin Enloe Medical Center Cohasset Glenn County BSC Admin Enloe Medical Center Esplanade Enloe Rehabilitation Center Orchard Hospital Oroville Hospital Colusa County Butte County BSC Admin Colusa Medical Center El Dorado County Hill Physicians Sacramento CalPERS Mercy General Hospital Mercy Medical Group CalPERS Methodist Hospital of Sacramento Mercy Hospital of Folsom Mercy San Juan Medical Center Fresno County Central Valley Medical Medical Providers Inc. Adventist Medical Center Reedley Sante Community Physicians Inc. Sante Health Systems Clovis Community Hospital Fresno Community Hospital Fresno Heart and Surgical Hospital A Community RMCC Fresno Surgical Hospital San Joaquin Valley Rehabilitation Hospital Selma Community Hospital St. Agnes Medical Center Glenn County Butte County BSC Admin Glenn Medical Center Glenn County BSC Admin Humboldt County Humboldt Del Norte IPA Mad River Community Hospital Redwood Memorial Hospital St. Joseph Hospital - Eureka Imperial County Imperial County Physicians Medical Group El Centro Regional Medical Center Pioneers Memorial Hospital Kern County Bakersfield Family Medical -

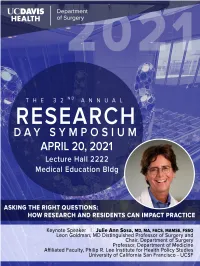

Program Notes Agenda | April 20Th, 2021

PROGRAM NOTES AGENDA | APRIL 20TH, 2021 TIME SESSION LOCATION 6:30 AM - 7:00 AM BREAKFAST AND REGISTRATION NORTH FOYER/ LH 2222 7:15 AM - 7:30 AM WELCOME AND INTRODUCTION LH 2222 7:30 AM - 9:00 AM ORAL PRESENTATIONS SESSION 1 LH 2222 9:00 AM - 9:15 AM BREAK 9:15 AM - 10:15 AM QUICK SHOT SESSION 1A LH 2222 9:15 AM - 10:15 AM QUICK SHOT SESSION 1B LH 1222 10:15 AM - 10:30 AM BREAK 10:30 AM - 12:00 PM ORAL PRESENTATIONS SESSION 2 LH 2222 12:00 PM - 12:30 PMPROGRAMLUNCH SCHEDULE | APRIL NORTH FOYER TH 12:30 PM - 1:30 PM KEYNOTE20 SPEAKER, 2021 PRESENTATION LH 2222 DR. JULIE ANN SOSA 1:30 PM - 3:00 PM ORAL PRESENTATION SESSION 3 LH 2222 3:00 PM - 3:15 PM BREAK 3:15 PM - 4:25 PM QUICK SHOT SESSION 2A LH 2222 3:15 PM- 4:25 PM QUICK SHOT SESSION 2B LH 1222 4:30 PM - 4:45 PM FINAL REMARKS LH 2222 5:00 PM - 6:00 PM AWARDS ANNOUNCEMENT LH 2222 3 PROGRAM SCHEDULE | SESSIONS IN LH 2222 6:30 AM - 7:00 AM BREAKFAST AND REGISTRATION 7:15 AM - 7:30 AM WELCOME AND INTRODUCTION ORAL PRESENTATIONS SESSION 1 LH 2222 | 7:30 AM - 9:00 AM MODERATORS - DR. KATHLEEN ROMANOWSKI & DR. BETHANY CUMMINGS 7:30 AM - 7:45 AM CHRISTINA THEODOROU - Efficacy of Clinical-Grade Human Placental Mesenchymal Stromal Cells in Fetal Ovine Myelomeningocele Repair 7:45 AM - 8:00 AM JOHN ANDRE - Major Psychiatric Illness and Substance Use Disorder influence mortality in major burn injury: a secondary analysis of the Transfusion Requirement in Burn Care Evaluation (TRIBE) study 8:00 AM - 8:15 AM SYLVIA CRUZ - Natural Killer and Cytotoxic T Cell Immune Infiltrates are Associated with -

Annual Report on Sustainable Practices

SUSTAINABLE PRACTICES TABLE OF CONTENTS Annual Report on Sustainable Practices 2016 ANNUAL REPORT 2016 1 SUSTAINABLE PRACTICES TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents A Message From the President ........................................................ 3 The Campuses ..................................................................................... 35 UC Berkeley .................................................................................... 36 Executive Summary ............................................................................. 4 UC Davis .......................................................................................... 40 UC Irvine .........................................................................................44 Overview of UC Sustainability ........................................................ 5 UCLA ................................................................................................ 48 UC Merced ...................................................................................... 52 UC Sustainable Practices Policies................................................... 7 UC Riverside ................................................................................... 56 Climate and Energy ......................................................................... 8 UC San Diego ................................................................................. 60 Transportation ............................................................................... 11 UC San Francisco .......................................................................... -

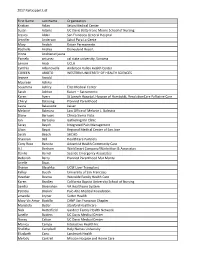

2017 Participant List First Name Last Name Organization Kristian Aclan

2017 Participant List First Name Last Name Organization Kristian Aclan Seton Medical Center Susan Adams UC Davis Betty Irene Moore School of Nursing Jessica Aldaz San Francisco General Hospital Jennifer Anderson Salud Para La Gente Mary Andich Kaiser Permanente Rochelle Andres Disneyland Resort Irinna Andrianarijaona Pamela antunez cal state university, Sonoma Lenore Arab UCLA Cynthia Arbanovella Anderson Valley Health Center COREEN ARIOTO WESTERN UNIVERSITY OF HEALTH SCIENCES Jeanne Arnold Maureen Ashiku Sosamma Ashley Elite Medical Center Sarah Ashton Kaiser -- Sacramento Karen Ayers St Joseph Hospital, Hospice of Humboldt, ResolutionCare Palliative Care Cheryl Balaoing Planned Parenthood Laura Balassone kaiser Melanie Balestra Law Office of Melanie L. Balestra Diane Barrows Clinica Sierra Vista Jan Bartuska Gathering Inn Clinic Seray Bayoh Integrated Pain Management Lilian Bayot Regional Medical Center of San Jose Sarah Beach SHCHD Shannon Bell HealthCare Partners Cony Rose Bencito Adventist Health Community Care A.J. Benham WorkSmart Company/Warbritton & Associates Danilo Bernal Seaside Emergency Associates Deborah Berry Planned Parenthood Mar Monte Arielle Bivas Sharon Blaschka UCSF Liver Transplant Kelley Booth University of San Francisco Heather Bosma Westside Family Health Care Karen Bradley California Baptist University School of Nursing Sandra Bresnahan VA Healthcare System Patricia Briskin` Palo Alto Medical Foundation amanda bryner Sutter Health Mary Vic Amor Bustillo CANP San Francisco Chapter Maristela Butler Stanford Healthcare -

Health and Psychological Services for UC Davis Health’S Medical Students, Residents & Faculty

Health and Psychological Services for UC Davis Health’s Medical Students, Residents & Faculty *In the event of an emergency, call 911 or go to the nearest emergency room* **Consider contacting your primary care physician if possible** UC Davis Police Emergency 916-734-2555 (Medical Center) 530-752-1230 (campus) National Suicide Prevention Lifeline 1-800-273-TALK (8255) Local Suicide Prevention and Crisis Hotlines 916-368-3111 (Sacramento) 530-756-5000 (Davis) Crisis Chat & Texting-WellSpace Health (not for emergent life threatening situations) https://www.wellspacehealth.org/services/counseling- prevention/suicide-prevention Sacramento County Adult Mental Health Services 916-875-1055 After hours line 888-881-4881 Sutter Center for Psychiatry Crisis Intervention Services 916-386-3620 (24 hours a day, 7 days a week) Heritage Oaks Hospital 916-489-3366 4250 Auburn Blvd. Sacramento, CA 95841 Sierra Vista Hospital 916-288-0300 8001 Bruceville Rd. Sacramento, CA 95823 University of California Davis Medical Center 916-734-3790 Emergency Department 2315 Stockton Blvd., Sacramento, CA 95817 Sutter General Hospital Emergency Services: 916-887-1130 2825 Capitol Avenue, Sacramento, CA 95816 Sutter Davis Emergency Department 530-757-5111 2000 Sutter Place, Davis, CA 95616 Mercy General Hospital 866-553-3261 Emergency Department 4001 J Street, Sacramento, CA 95819 Mercy San Juan Medical Center 855-409-5280 Emergency Department 6501 Coyle Avenue, Carmichael, CA 95608 Methodist Hospital of Sacramento 916-230-1873 Emergency Department 7500 Hospital Drive, -

YCTD 2019August Minutes

AGENDA If requested, this agenda can be made available in appropriate alternative formats to persons with a disability, as required by Section 202 of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 and the Federal Rules and Regulations adopted in implementation thereof. Persons seeking an alternative format should contact Kathy Souza, Executive Assistant, for further information. In addition, a person with a disability who requires a modification or accommodation, including auxiliary aids or services, in order to participate in a public meeting should telephone or otherwise contact Kathy Souza as soon as possible and preferably at least 24 hours prior to the meeting. Kathy Souza may be reached at telephone number (530) 402-2819 or at the following address: 350 Industrial Way, Woodland, CA 95776. It is the policy of the Board of Directors of the Yolo County Transportation District to encourage participation in the meetings of the Board of Directors. At each open meeting, members of the public shall be provided with an opportunity to directly address the Board on items of interest to the public that are within the subject matter jurisdiction of the Board of Directors. Please fill out a speaker card and give it to the Board Clerk if you wish to address the Board. Speaker cards are provided on a table by the entrance to the meeting room. Depending on the length of the agenda and number of speakers who filled out and submitted cards, the Board Chair reserves the right to limit a public speaker’s time to no more than three (3) minutes, or less, per agenda item. -

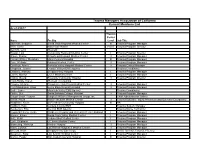

Trauma Managers Association of California Current Members List As of 4/30/17

Trauma Managers Association of California Current Members List As of 4/30/17 Trauma Center Name Facility Level Job Title Bateman, Bridgette Sierra Vista Regional Medical Center III Trauma Program Manager Behr, Lynne Kaiser San Rafael EDAT Trauma Program Director Bennink, Lynn (Retired) Blough, Lois Community Regional Medical Center I Trauma Program Director Brown, Sharon Arrowhead Regional Medical Center II Trauma Program Manager Carroll (White), Meaghan Marin General Hospital III Trauma Program Manager Case, Melinda Palomar Medical Center II Trauma Program Manager Castillejo, Aimee Pomona Valley Hospital Medical Center II Trauma Clinical Manager Chapman, Joanne Coastal Valleys EMS Agency Trauma Coordinator Chiatello, Anthony Scripps Mercy Hospital I Trauma Program Manager Cohen, Marilyn UCLA Medical Center I Trauma Program Manager Collins, Georgi Riverside Community Hospital II Trauma Program Director Crain-Riddle, Karen (Retired) / Consulting Crowley, Melanie Providence Holy Cross Medical Center II Trauma Program Manager Cruz-Manglapus, Gilda Henry Mayo Newhall Hospital II Trauma Program Manager Doyle, Lance Mountain-Valley EMS Agency Trauma Coordinator Fortier, Sue Santa Barbara Cottage Hospital II Trauma Program Manager Gough-Smith, Robynn Surgical Affiliates Management Group, Inc. Chief Administrative Officer Green, Paula Kaiser Vacaville Medical Center II Trauma Educator, Injury Prevention and Outreach Coordinator Haddleton, Kevin St.Elizabeth Community Hospital III RN Hadduck, Katy Ventura County EMS Trauma System Manager Henderson, -

1400 Tenth Street, Sacramento, CA 95814 SCH

Appendix C Notice of Completion & Environmental Document Transmittal Mail to: State Clearinghouse, P.O. Box 3044, Sacramento, CA 95812-3044 (916) 445-0613 For Hand Delivery/Street Address: 1400 Tenth Street, Sacramento, CA 95814 SCH # Project Title: UC Davis Sacramento Campus Long Range Development Plan Lead Agency: The Regents of the University of California Contact Person: Tom Rush Mailing Address: 4800 2nd Avenue, Suite 3010 Phone: (916) 734-3811 City: Sacramento Zip: 95817 County: Sacramento Project Location: County: Sacramento City/Nearest Community: Sacramento Cross Streets: Stockton Boulevard and Broadway Street Zip Code: 95817 Longitude/Latitude (degrees, minutes and seconds): 38 22 40 N / 121 27 64 W Total Acres: 142 Assessor's Parcel No.: Section: 17 Twp.: 8N Range: 5E Base: Diablo Within 2 Miles: State Hwy #: 50 and 99 Waterways: A merican River Airports:Sacramento Executive Railways: UPRR Schools: Marion Anderson Document Type: CEQA: ✔ NOP Draft EIR NEPA: NOI Other: Joint Document Early Cons Supplement/Subsequent EIR EA Final Document Neg Dec (Prior SCH No.) Draft EIS Other: Mit Neg Dec Other: FONSI Local Action Type: General Plan Update Specific Plan Rezone Annexation General Plan Amendment Master Plan Prezone Redevelopment General Plan Element Planned Unit Development Use Permit Coastal Permit Community Plan Site Plan Land Division (Subdivision, etc.) ✔ Other: LRDP Development Type: Residential: Units Acres Office: Sq.ft. Acres Employees Transportation: Type Commercial: Sq.ft. Acres Employees Mining: Mineral Industrial: -

Trauma Managers Association of California Current Members List As of 2/23/18

Trauma Managers Association of California Current Members List As of 2/23/18 Trauma Center Name Facility Level Job Title Anderson, Melissa Children's Hospital Los Angeles I Trauma Program Manager Ayers, Kathi Sharp Memorial Hospital II Trauma Program Manager Bartleson, BJ California Hospital Association VP Nursing & Clinical Services Bateman, Bridgette Sierra Vista Regional Medical Center III Trauma Program Manager Becker, Debra Central California EMS Agency Specialty Services Coordinator Behr, Lynne Kaiser San Rafael EDAT Trauma Program Director Bennink, Lynn (Retired) Blough, Lois Community Regional Medical Center I Trauma Program Director Brammer, Amy Kaiser Vacaville Medical Center II Trauma Program Director Brown, Sharon Arrowhead Regional Medical Center II Trauma Program Manager Carroll (White), Meaghan Marin General Hospital III Trauma Program Manager Cartner, Jan Doctors Medical Center II Trauma Program Manager Case, Melinda Palomar Medical Center II Trauma Program Manager Castillejo, Aimee Pomona Valley Hospital Medical Center II Trauma Clinical Manager Chapman, Joanne Coastal Valleys EMS Agency Trauma Coordinator Chiatello, Anthony Scripps Mercy Hospital I Trauma Program Manager Cohen, Marilyn UCLA Medical Center I Trauma Program Manager Collins, Georgi Riverside Community Hospital II Trauma Program Director Crain-Riddle, Karen (Retired) / Consulting Crowley, Melanie Huntington Hospital II Trauma Program Manager Cruz-Manglapus, Gilda Henry Mayo Newhall Hospital II Trauma Program Manager Dice, Robert Santa Rosa Memorial Hospital -

Match Day Brings Smiles, Tears to Pappas Quad

MARCH 24 • 2017 PUBLISHED FOR THE USC HEALTH SCIENCES CAMPUS COMMUNITY VOLUME 1 4 • NUMBER• NUMBER 2 6 John S. Oghalai tapped to lead otolaryngology ohn S. Oghalai, MD, has been recruitedJ to serve as the new chair of the USC Tina and Rick Caruso Department of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery, effective Aug. 1. Courtesy John S. Oghalai Courtesy He joins the Keck John S. Oghalai School of Medicine of USC from Stanford University School of Medicine after a national search, according to Rohit Varma, MD, MPH, dean of the Keck School and director of the USC Gayle and Edward Roski Eye Institute. “We look forward to Dr. Oghalai’s arrival in August and have great expectations for him to continue the department’s ascending trajectory in quality clinical care, resident and fellow Ricardo Carrasco III Carrasco Ricardo education, and research,” Varma said in a memo Maria de Fátima Reyes shows her match results to gathered friends and family during Match Day celebrations on March 17 at Pappas Quad. announcing Oghalai’s recruitment. “Please join us in welcoming him to the Trojan family.” Oghalai has been a professor in the Match Day brings smiles, See OGHALAI, page 2 tears to Pappas Quad Grant to fund By Leigh Bailey model for heers, tears and champagne toasts rang across the Harry elder abuse andC Celesta Pappas Quad in the morning sunshine as the Keck School of Medicine of USC’s class intervention of 2017 learned where they would By Claire Norman be spending their next few years of training as medical professionals.