Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chap6.Pdf (133.3Kb)

Chapter VI The Nation-State as an Ecological Communicator: The Case of Indian Nuclear Tests While nations have always communicated about (their) ecologies—let’s say, through religious rituals and performances and literary narratives—nation-states have only recently come to assume a prominent role in that arena. In fact, nation-states at large have become important communicators outside the fields of law and order, geopolitics, and diplomacy only recently. (The public controversies related to the stands taken by the Chinese, Canadian, and Singaporean governments on SARS are but the latest examples.) The two primary factors behind the increased eminence of the nation- state as an ecological communicator are simple: and are effective distinctively on the levels of nation and communication. One: Nations have, on the one hand, been increasingly subsumed by the images and effects of their states—rather than being understood as cultures or civilizations at large;1 on the other hand, they have also managed to liberate themselves, especially since the Second World War, from the politically incestuous visions of erstwhile royal families (colonial or otherwise). On the former level, the emergence of the nation-state as the player on the political landscape has had to do with an increasingly formal redefining of national boundaries at the expense of cultural and linguistic flows or ecological continua across landmasses. On the latter level, while administrative, military, and other governing apparatuses were very important through colonialism, empires were at once too geographically expansive and politically concentrated in particular clans to have allowed the nation-state to dominate over public imagination (except as extensions of the clans). -

The Intimate Enemy

THE INTIMATE ENEMY Loss and Recovery of Self under Colonialism ASHIS NANDY DELHI OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS BOMBAY CALCUTTA MADRAS The Psychology of Colonialism 2 One other elements too. The political economy of colonization is of course important, but the crudity and inanity of colonialism are principally The Psychology of Colonialism: expressed in the sphere of psychology and, to the extent the variables Sex, Age and Ideology used to describe the states of mind under colonialism have themselves become politicized since the entry of modern colonialism on the in British India world scene, in the sphere of political psychology. The following pages will explore some of these psychological contours of colonialism in the rulers and the ruled and try to define colonialism as a shared culture which may not always begin with the establishment of alien I rule in a society and end with the departure of the alien rulers from the colony. The example I shall use will be that of India, where a Imperialism was a sentiment rather than a policy; its foundations were moral rather than intellectual. colonial political economy began to operate seventy-five years before D. C. Somervell1 the full-blown ideology of British imperialism became dominant, and where thirty-five years after the formal ending of the Raj, the ideology It is becoming increasingly obvious that colonialism—as we have of colonialism is still triumphant in many sectors of life. come to know it during the last two hundred years— cannot be Such disjunctions between politics and culture became possible identified with only economic gain and political power. -

Ranchi to 1580 and That in Seven People Were Found Infect- Fatality Rate Was 1.20 Per Cent

$ 7 " ! * 8 8 8 +,$-+%./0 #&'&'( -. )#*+, : '+"?+;(((# 5+;'+ ,-,+ 25'+";2+ "2'-,')4(3 ;-(+';-);+23+# #+-,#+,)# -+",5+#- 22+#<2=,'@ 4,''+ '2+ A #(+ ,+/ "2-#+") -<"2#+;+"=,>+<3+"+ 9' !*% ++& 6. 9+ 2 !+ 1 .1232.45.26 Q $$%&$ ' R R ) ')4(3 !"# n a serious allegation 23"2'-, Ithat raised the polit- ical temperature in est Bengal's Governor Jagdeep Uttar Pradesh, AAP ! ! WDhankhar, who has been in the and Samajwadi Party news for his frequent run-ins with Chief leaders, in different Minister Mamata Banerjee, has six press conferences, lev- P Officers on Special Duty (OSD) while eled a sensational charge of financial irregular- Rajasthan Governor Kalraj Mishra has ities in land purchase by the Ram Janmabhoomi "! 23"2'-, only one OSD. Trust, which was set up by the Centre for the #$ According to the websites of the dif- construction of the Ram Temple in Ayodhya. ! rime Minister Narendra ferent State Governments, there are four AAP MP Sanjay Singh held a press confer- % ! PModi on Sunday stressed OSD to Bihar Governor and two OSDs ence in Lucknow while former SP MLA and for- ! the need for open and democ- to the Uttar Pradesh (UP) Governor. mer Minister Pawan Pandey addressed reporters ! ! ratic societies to work togeth- ! Similarly, Chhattisgarh and Odisha Bhawan, there is no OSD to Governor in Ayodhya. Ramjanmabhumi Tirth Kshetra er to defend the values they #$ Governors have two OSDs each. Anandiben Patel. There is only one post Trust general secretary Champat Rai said that ! P hold dear and to respond to the The OSD is an officer in the Indian of OSD to Governor in Haryana which they will study the charges of land purchase " increasing global challenges. -

The Twilight of Certitudes: Secularism, Hindu Nationalism and Other Masks of Deculturation

The Twilight of Certitudes: Secularism, Hindu Nationalism and Other Masks of Deculturation hat follows is basically a series of propositions. It is not meant for academics grappling with the issue of ethnic and religious Wviolence as a cognitive puzzle, but for concerned intellectuals and grass-roots activists trying, in the language of Gustavo Esteva, to 'regenerate people's space'* Its aim is three-fold: (1) to systematize some of the available insights into the problem of ethnic and communal violence in South Asia, particularly India, from the point of vi-?w bTthose who do not see communal ism and secularism as sworn enemies but as the disowned doubles of each other; (2) to acknowledge, as part of the same exercise, that Hindu nationalism, like other such eth no-national isms is not an 'extreme' form of Hinduism but a modem creed which seeks, on behalf of the global nation-state system, to retool Hinduism into a national ideology and the Hindus into a 'proper' nationality; and (3) to hint at an approach to religious tolerance in a democratic polity that is not dismissive towards the ways of life, idioms and modes of informal social and political analyses of the citizens even when they happen to be unacquainted with—or inhospitable to—the ideology of secularism. I must make one qualification at the beginning. This is the third in a series of papers on secularism, in which one of my main concerns has been to examine the political and cultural-psychological viability of the ideology of secularism and to argue that its fragile status in South Asian politics is culturally 'natural' but not an unmitigated disaster. -

FINAL DISTRIBUTION.Xlsx

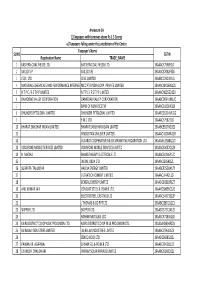

Annexure-1A 1)Taxpayers with turnover above Rs 1.5 Crores a) Taxpayers falling under the jurisdiction of the Centre Taxpayer's Name SL NO GSTIN Registration Name TRADE_NAME 1 EASTERN COAL FIELDS LTD. EASTERN COAL FIELDS LTD. 19AAACE7590E1ZI 2 SAIL (D.S.P) SAIL (D.S.P) 19AAACS7062F6Z6 3 CESC LTD. CESC LIMITED 19AABCC2903N1ZL 4 MATERIALS CHEMICALS AND PERFORMANCE INTERMEDIARIESMCC PTA PRIVATE INDIA CORP.LIMITED PRIVATE LIMITED 19AAACM9169K1ZU 5 N T P C / F S T P P LIMITED N T P C / F S T P P LIMITED 19AAACN0255D1ZV 6 DAMODAR VALLEY CORPORATION DAMODAR VALLEY CORPORATION 19AABCD0541M1ZO 7 BANK OF NOVA SCOTIA 19AAACB1536H1ZX 8 DHUNSERI PETGLOBAL LIMITED DHUNSERI PETGLOBAL LIMITED 19AAFCD5214M1ZG 9 E M C LTD 19AAACE7582J1Z7 10 BHARAT SANCHAR NIGAM LIMITED BHARAT SANCHAR NIGAM LIMITED 19AABCB5576G3ZG 11 HINDUSTAN UNILEVER LIMITED 19AAACH1004N1ZR 12 GUJARAT COOPERATIVE MILKS MARKETING FEDARATION LTD 19AAAAG5588Q1ZT 13 VODAFONE MOBILE SERVICES LIMITED VODAFONE MOBILE SERVICES LIMITED 19AAACS4457Q1ZN 14 N MADHU BHARAT HEAVY ELECTRICALS LTD 19AAACB4146P1ZC 15 JINDAL INDIA LTD 19AAACJ2054J1ZL 16 SUBRATA TALUKDAR HALDIA ENERGY LIMITED 19AABCR2530A1ZY 17 ULTRATECH CEMENT LIMITED 19AAACL6442L1Z7 18 BENGAL ENERGY LIMITED 19AADCB1581F1ZT 19 ANIL KUMAR JAIN CONCAST STEEL & POWER LTD.. 19AAHCS8656C1Z0 20 ELECTROSTEEL CASTINGS LTD 19AAACE4975B1ZP 21 J THOMAS & CO PVT LTD 19AABCJ2851Q1Z1 22 SKIPPER LTD. SKIPPER LTD. 19AADCS7272A1ZE 23 RASHMI METALIKS LTD 19AACCR7183E1Z6 24 KAIRA DISTRICT CO-OP MILK PRO.UNION LTD. KAIRA DISTRICT CO-OP MILK PRO.UNION LTD. 19AAAAK8694F2Z6 25 JAI BALAJI INDUSTRIES LIMITED JAI BALAJI INDUSTRIES LIMITED 19AAACJ7961J1Z3 26 SENCO GOLD LTD. 19AADCS6985J1ZL 27 PAWAN KR. AGARWAL SHYAM SEL & POWER LTD. 19AAECS9421J1ZZ 28 GYANESH CHAUDHARY VIKRAM SOLAR PRIVATE LIMITED 19AABCI5168D1ZL 29 KARUNA MANAGEMENT SERVICES LIMITED 19AABCK1666L1Z7 30 SHIVANANDAN TOSHNIWAL AMBUJA CEMENTS LIMITED 19AAACG0569P1Z4 31 SHALIMAR HATCHERIES LIMITED SHALIMAR HATCHERIES LTD 19AADCS6537J1ZX 32 FIDDLE IRON & STEEL PVT. -

The Intimate Enemy As a Classic Post-Colonial Study of M

critical currents Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation Occasional Paper Series Camus and Gandhi Essays on Political Philosophy in Hammarskjöld’s Times no.3 April 2008 Beyond Diplomacy – Perspectives on Dag Hammarskjöld 1 critical currents no.3 April 2008 Camus and Gandhi Essays on Political Philosophy in Hammarskjöld’s Times Lou Marin Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation Uppsala 2008 The Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation pays tribute to the memory of the second Secretary-General of the UN by searching for and examining workable alternatives for a socially and economically just, ecologically sustainable, peaceful and secure world. Critical Currents is an In the spirit of Dag Hammarskjöld's Occasional Paper Series integrity, his readiness to challenge the published by the dominant powers and his passionate plea Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation. for the sovereignty of small nations and It is also available online at their right to shape their own destiny, the www.dhf.uu.se. Foundation seeks to examine mainstream understanding of development and bring to Statements of fact or opinion the debate alternative perspectives of often are those of the authors and unheard voices. do not imply endorsement by the Foundation. By making possible the meeting of minds, Manuscripts for review experiences and perspectives through the should be sent to organising of seminars and dialogues, [email protected]. the Foundation plays a catalysing role in the identifi cation of new issues and Series editor: Henning Melber the formulation of new concepts, policy Language editor: Wendy Davies proposals, strategies and work plans towards Layout: Mattias Lasson solutions. The Foundation seeks to be at the Printed by X-O Graf Tryckeri AB cutting edge of the debates on development, ISSN 1654-4250 security and environment, thereby Copyright on the text is with the continuously embarking on new themes authors and the Foundation. -

Vaccine ‘War’ Continues

y k y cm RIGHT RESOLVE WAR-LIKE SITUATION PERSISTS POWAR REAPPOINTED Actor Priyanka Chopra Jonas has raised USD The ongoing conflict between Israel and the Hamas Ramesh Powar is reappointed as Indian 1mn to help India fight the 2nd wave of continued with both sides indulging in rocket women’s cricket team head coach in place of WV Raman the Covid-19 pandemic LEISURE | P2 attacks and airstrikes INTERNATIONAL | P10 SPORTS | P12 VOLUME 11, ISSUE 43 | www.orissapost.com BHUBANESWAR | FRIDAY, MAY 14 | 2021 12 PAGES | `4.00 IRREGULAR by MANJUL 11 GOVTS INCLUDING ODISHA FLOAT GLOBAL TENDERS TO GET JABS FROM ABROAD Vaccine ‘war’ continues AGENCIES NOW VENTILATOR New Delhi, May 13: Due to an acute WOES SURFACE shortage of Covid-19 vaccines, India ‘RATE OF INFECTION WORRYING’ is struggling to contain the second NEW DELHI: Only the supply of By the time wave of the pandemic. Even though vaccines to the different states is my turn comes, the two main vaccine producers in not bothering the Centre alone. Well I will be 18! the country, Serum Institute of India it has another problem in hand. The Lockdown may (SII) and Bharat Biotech have assured ‘Make in India’ ventilators are the government that they are ramp- developing glitches in many states ing up productions, it seems that the thus creating another challenge for UPSC examination the Centre. The Centre has said states are not buying this. So far 11 continue in state ‘many hospitals or medical colleges states including Odisha have floated deferred to Oct 10 are not following’ the user manual global tenders to procure vaccines properly leading to the technical POST NEWS NETWORK (38.4%), Khurda (36.7%), NEW DELHI: The Union Public from abroad. -

India Legal Forum

MARCH 2021 Volume IV ALL INDIA LEGAL FORUM CREDITS:- • Patron-in-Chief: Aayush Akar • Editor-in-Chief: Shubhank Suman • Senior Manager: Vrinda Khanna, Nandini Mangla • Manager- Deepanshu Kaushik • Researchers: 1. Praveen Parihar 2. Tania Maria Joy 3. Santhosh Murugan 4. Yamini Mahawar 5. Aini Borah 6. Deepanshi Gupta 7. Fazila Fahim 8. Ishika Sharma 9. Padma Priya 10. Rishika Mahajan 11. Sneha Bachhawat 12. Uma Bharathi • Editors 1. Shubh Jaiswal 1 IN THE ISSUE LEGAL NEWS except in circumstances where his release will bring him in association with any Court sets aside Juvenile Justice Board order, grants Bail to Juvenile in Theft known criminal or expose him to moral, Case physical or psychological danger, or the release would defeat the ends of justice. “There is no sufficient material on record to show that the appellant/child will come into the association with any known criminal as the full particulars of the criminal with whom the delinquent appellant is likely to come into association with,” the special court said, adding that the JJB had erred in 22-3-2021 not releasing the juvenile on bail. Special Court earlier this week The Court further said that the child in set aside the order of a Juvenile conflict with law would get the benefit of A Justice Board (JJB), which had Section 12 (1) of the Act, which contains denied bail to a 17-year-old boy on the the principles for bail. apprehension that he may come in contact The N M Joshi Marg police had booked with anti-social elements. four youngsters, including the teen, for The Court granted bail to the minor, who allegedly robbing a shop early last year at had spent over 3 months in jail in a theft Phoenix mall in central Mumbai & stealing case, even as the adult co-accused in the an iPhone along with Rs 700. -

SCIENCE, HEGEMONY & VIOLENCE a REQUIEM for MODERNITY Edited by Ashis Nandy Preface

SCIENCE, HEGEMONY & VIOLENCE A REQUIEM FOR MODERNITY Edited by Ashis Nandy (UNITED NATIONS UNIVERSITY) Preface This set of essays, the first in a series of three volumes, has grown out of the collaborative efforts of a group of scholars who have individually been interested in the problems of science and culture for over a decade. They were brought together by a three-year study of science and violence, which in turn was part of a larger Programme on Peace and Global Transformation of the United Nations University. We are grateful to the directors of the programme, Rajni Kothari and Giri Deshingkar, and to the United Nations University for this opportunity to explore jointly, on an experimental basis, a particularly amorphous intellectual problem from outside the formal boundaries of professional philosophy, history and sociology of science. It is in the nature of such an enterprise for intellectual controversies to erupt at virtually every step, and the authors of the volume are particularly grateful for the collaboration of scholars and organizations which hold very different positions on the issues covered in this volume. However, it goes without saying that the views expressed and the analysis presented in the following pages are solely those of the authors. That these views are often strongly expressed only goes to show that the United Nations University is tolerant not only of dissenting ideologies but also of diverse styles of articulating them. The volume has also gained immensely from detailed comments and criticisms from a number of scholars, writers, editors and science activists. We remember with much gratitude the contributions of Giri Deshingkar, in his incarnation as a student of Chinese science, Edward Goldsmith, Ward Morehouse, M. -

Lok Sabha Debates

LOK SABHA DEBATES LOK SABHA Rule 9 of the Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business in Lok Sabha, I have nominated the following Members as members of the Panel of Chairman : Saturday. March 28, 199B/Chaitra 7, 1. Shri. P.M. Sayeed 1920 (Saka) 2. Shri K. Pradhanl 3. Dr. Laxminarayan Pandey 4. Prof. RHa Verma The Lok Sabha met at two minute past 5. Shrl K. Yerrannaldu Eleven of the Clock. 6. Shri V. Sathiamoorthy 7. Shri Basu Deb Acharla SPEAKER in the Chail1 1M". SHRI SUDIP BANDYOPADHYAY (Calculla North· [English} West) : II will be appreciated if they are introduced to MR. SPEAKER : There is an announcement. the House. THE MINISTER OF HOME AFFAIRS (SHRI l.K. AN HON. MEMBER: II is not necessary. ADVANI) : Mr. Speaker Sir, we are about to resume the debate on the Motion of Confidence. I would request that the time for voting be announced. We tentatively 11.04 hra. agreed the other day that the reply to the debate by the Prime Minister would be fixed at 4 p.m. then by 5 p.m. or so, we can have the voting because many Members REPORT OF COMMITIEE OF PRIVILEGES would like to go back to their constituencies, they have (ELEVENTH LOK SABHA) ON 'ETHICS, to fill their returns etc. Otherwise, we have no objection STANDARDS IN PUBLIC LIFE, PRIVILEGES, silling late. Because of practical considerations, it would FACILITIES TO MEMBERS AND OTHER ba proper if we all agree to a certain time limit. RELATED MATIERS'·LAID SHRI SHARAD PAWAR (Baramati) : There is a request from outside also that many Members would [English] like to go back to their respective constituencies to SECRETARY·GENERAL : The Chairman, Commillee submit. -

Response to Nandy Arjun Guneratne Macalester College

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DigitalCommons@Macalester College Macalester International Volume 4 The Divided Self: Identity and Globalization Article 24 Spring 5-31-1997 Response to Nandy Arjun Guneratne Macalester College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/macintl Recommended Citation Guneratne, Arjun (1997) "Response to Nandy," Macalester International: Vol. 4, Article 24. Available at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/macintl/vol4/iss1/24 This Response is brought to you for free and open access by the Institute for Global Citizenship at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Macalester International by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 04/15/97 4:35 PM 0918gun3.qxd Response Arjun Guneratne I. Introduction Dr. Nandy’s essay is a thoughtful and stimulating critique of the failure of the modern Indian state by one of India’s most impor- tant intellectual figures. It is an extended reflection on the part played by India’s Westernized political and intellectual elite in the rise of communalism and ethnic chauvinism in modern India. It is this elite (the modern Indians) who are the vehicles for the modern political self that is the subject of Dr. Nandy’s essay. He attributes this failure in large part to the dependence of this elite on concepts of the state and statecraft uncritically derived from European political philosophy, which have little to do with actual Indian experience or tradition. Modern India is characterized here as urban, elite, male, and historically informed; its counterpart, traditional India, is rural, subaltern, female, and informed by an understanding of the past shaped by myths and legends. -

History's Forgotten Doubles Author(S): Ashis Nandy Reviewed Work(S): Source: History and Theory, Vol

Wesleyan University History's Forgotten Doubles Author(s): Ashis Nandy Reviewed work(s): Source: History and Theory, Vol. 34, No. 2, Theme Issue 34: World Historians and Their Critics (May, 1995), pp. 44-66 Published by: Blackwell Publishing for Wesleyan University Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2505434 . Accessed: 31/07/2012 17:22 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Blackwell Publishing and Wesleyan University are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to History and Theory. http://www.jstor.org HISTORY'S FORGOTTEN DOUBLES' ASHIS NANDY ABSTRACT The historical mode may be the dominant mode of constructing the past in most parts of the globe but it is certainly not the most popular mode of doing so. The dominance is derived from the links the idea of history has established with the modern nation-state, the secular worldview, the Baconian concept of scientific rationality, nineteenth-century theories of progress, and, in recent decades, development. This dominance has also been strengthenedby the absence of any radical critique of the idea of history within the modern world and for that matter, within the discipline of history itself.