W23 Flintham (Page 1)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

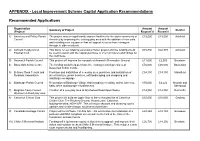

APPENDIX - Local Improvement Scheme Capital Application Recommendations

APPENDIX - Local Improvement Scheme Capital Application Recommendations Recommended Applications Organisation Amount Amount Summary of Project District (Project) Request’d Recom’d 1) Annesley and Felley Parish The project aims to significantly improve facilities for the wider community of £19,500 £19,500 Ashfield Council Annesley by improving the existing play area with the addition of new units and installing new equipment that will appeal to users from teenagers through to older residents. 2) Ashfield Rugby Union This bid is for our 'Making Larwood a Home' project and the funding would £45,830 £22,915 Ashfield Football Club be used to assist with the capital purchase of internal fixtures and fittings for the clubhouse. 3) Awsworth Parish Council This project will improve the car park at Awsworth Recreation Ground. £11,000 £2,000 Broxtowe 4) Bassetlaw Action Centre The funding would help purchase the existing (rented) premises at £50,000 £20,000 Bassetlaw Bassetlaw Action Centre. 5) Bellamy Road Tenant and Provision and installation of new play area, purchase and installation of £34,150 £34,150 Mansfield Resident Association street furniture, picnic benches, soft landscaping and designing and installing new signage 6) Bilsthorpe Parish Council Restoration of Bilsthorpe Village Hall including re-roofing, toilets, kitchens, £50,000 £2,222 Newark and halls, office and storage refurbishment. Sherwood 7) Bingham Town Council Creation of a new play area at Wychwood Road Open Space. £14,950 £14,950 Rushcliffe Wychwood Road play area 8) Calverton Cricket Club This project will build an upper floor to the cricket pavilion at Calverton £35,000 £10,000 Gedling Cricket Club, The Rookery Ground, Woods Lane, Calverton, Nottinghamshire, NG14 6FF. -

Issues and Options Rushcliffe Local Plan Part 2: Land and Planning

Rushcliffe Local Plan Rushcliffe Borough Council Rushcliffe Local Plan Part 2: Land and Planning Policies Issues and Options January 2016 Local Plan Part 2: Land and Planning Policies Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Housing Development 6 3. Green Belt 31 4. Employment Provision and Economic Development 36 5. Regeneration 47 6. Retail Centres 49 7. Design and Landscape Character 55 8. Historic Environment 57 9. Climate Change, Flood Risk and Water Use 59 10. Green Infrastructure and Biodiversity 63 11. Culture, Tourism and Sports Facilities 69 12. Contamination and Pollution 72 13. Transport 75 14. Telecommunications Infrastructure 77 15. General 78 Appendices 79 Appendix A: Alterations to existing Green Belt ‘inset’ boundaries 80 Appendix B: Creation of new Green Belt ‘inset’ boundaries 89 Appendix C: District and Local Centres 97 Appendix D: Potential Centres of Neighbourhood Importance 105 i Local Plan Part 2: Land and Planning Policies Appendix E: Difference between Building Regulation and 110 Planning Systems Appendix F: Glossary 111 ii Local Plan Part 2: Land and Planning Policies 1. Introduction Rushcliffe Local Plan The Rushcliffe Local Plan will form the statutory development plan for the Borough. The Local Plan is being developed in two parts, the Part 1 – Core Strategy and the Part 2 – Land and Planning Policies (LAPP). The Council's aim is to produce a comprehensive planning framework to achieve sustainable development in the Borough. The Rushcliffe Local Plan is a ‘folder’ of planning documents. Its contents are illustrated by the diagram below, which also indicates the relationship between the various documents that make up the Local Plan. -

Reservoirs of Hope Full Report

FULL PRACTITIONER ENQUIRY REPORT SPRING 2003 Reservoirs of Hope: Spiritual and moral leadership in headteachers How headteachers sustain their schools and themselves through spiritual and moral leadership based on hope. Alan Flintham, Headteacher, Quarrydale School, Sutton-in-Ashfield, Nottinghamshire Contents Introduction 3 Summary of findings 6 Main findings: 8 1. The foundations of the reservoir: spiritual and moral bases of headship 8 2. Reservoirs of hope: towards a metaphor for spiritual and moral leadership 11 3. Replenishing the reservoirs: sustainability strategies in headship 15 4. Testing the reservoirs: the response to critical incidents 21 5. Developing the reservoirs: the growth of capacity 25 6. Building new reservoirs: the transference of capacity 29 Methodology 36 Acknowledgements 39 Bibliography 40 National College for School Leadership 2 Introduction The research concept “The starting point is not policy, it’s hope. Because from hope comes change” (Tony Blair, 2002) This research study seeks to test this statement against the leadership stories of 25 serving headteachers drawn from a cross-section of school contexts, phases and geographical locations within England. It is based on the premise that a school cannot move forward without a clear vision of where its leaders want it to reach. Without such a vision, clearly articulated, it remains static at best or at worst regresses, for ‘without vision the people perish’. ‘Hope’ is what drives the institution forward towards achieving its vision, whilst allowing it to remain true to its values whatever the external pressures. The successful headteacher, through acting as the wellspring of values and vision for the school thus acts as the external ‘reservoir of hope’ for the institution. -

Landowner Declaration Register

Landowner Declaration Register This is maintained under Section 31A of the Highways Act 1980 and Section 15B(1) of the Commons Act 2006. It comprises: Landowner deposit under S.15A(1) of the Commons Act 2006 By depositing a statement, landowners can prevent their land being registered as a Town or Village Green, provided they make the deposit before there has been 20 years recreational use of the land as of right. A new statement must be deposited within 20 years. Landowner deposit under S.31(6) of the Highways Act 1980 Highway statements and highway declarations allow landowners to prevent their land being recorded as a highway on the definitive map on the basis of presumed dedication (usually 20 years uninterrupted use). A highway statement or declaration must be followed by a further declaration within 20 years (or 10 years if lodged prior to 1 October 2013). Last Updated: September 2015 Ref Parish Landowner Details of land Highways Act 1980 CA1 Documents No. Section 31(6) 6 Date of Expiry date initial deposit A1 Alverton M P Langley The Belvedere, Alverton 17/07/2008 17/07/2018 A2 Annesley Multi owners Annesley Estate 30/03/1998 30/03/2004 expired A3 Annesley Notts Wildlife Trust Annesley Woodhouse Quarry 11/07/1997 13/01/2013 expired A4 Annesley Taylor Wimpey UK Little Oak Plantation 11/04/2012 11/04/2022 Ltd A5 Arnold Langridge Homes Ltd Lodge Farm, off Georgia Avenue 05/01/2009 05/01/2019 A6 Arnold Langridge Homes Ltd Land off Kenneth Road 05/01/2009 05/01/2019 A7 Arnold Langridge Homes Ltd Land off Calverton Road 05/11/2008 05/11/2018 -

Flintham Primary School-Contamination Appraisal2

Nottinghamshire County Council Environment & Resources Flintham Primary School Inholms Road, Flintham, Contamination Appraisal Report Reference: P.Y.BE.28909.01 Tim Gregory Corporate Director Environment & Resources Trent Bridge House Fox Road West Bridgford Nottingham NG2 6BJ Date: January 2014 P.Y.BE.28909.01/Flintham Primary School, Flintham -Contamination Appraisal 1 QUALIFICATIONS & LIMITATIONS The following notes should be read in conjunction with the report:- The report has been prepared and written solely for the purpose of providing information in regard to contamination relevant to the proposed Flintham Primary School Basic Needs Improvement Scheme and its contents should not be used out of that context. Furthermore, new information, changed practices or new legislation may necessitate revised interpretation of the report after the date of its submission. Unless specifically referred to, the report has not addressed environmental planning issues or liabilities relating to health. All information, comments and opinions given in the Desk Study and Preliminary Site Investigation report are based on the information given or obtained. Information searches cannot be exhaustive and there may be undiscovered records. Nottinghamshire County Council, Communities Department, Landscape and Reclamation Team prepared this report for the sole and exclusive use of Nottinghamshire County Council, Property Strategy and Development Team in response to specific instructions. Other parties using the information contained in this report do so at their -

91-354-Bus-Timetable.Pdf

Newark East Stoke Sibthorpe Screveton Newton Service 91/354 91/354 Farndon Elston Flintham East Bingham Bridgford Newark - Elston - East Bridgford - Bingham 91/354 Monday to Saturday Operator: NOT ML NOT ML ML ML ML ML NOT NOT Service: 354 91 354 91 91 91 91 91A 354 354 Notes: Sch NEWARK, North Gate Rail Station 0600 0650 0705 0850 1050 1150 1350 1515 1700 1820 Newark, Lombard Street 0608 0655 0713 0855 1055 1155 1355 1520 1708 1828 Newark, Magnus School Bus Park …. …. …. …. …. …. …. 1523 …. …. Farndon, The Copse, Hawthorne Crescent …. 0702 …. 0902 1102 1202 1402 1531 …. …. Farndon, Main Street, Grays Court 0613 0704 0718 0904 1104 1204 1404 1533 1713 1832 ELSTON, Toad Lane 0626 0712 0731 0912 1112 1212 1412 1540 1726 1844 Sibthorpe, Main Street 0632 0716 0737 0916 1116 1216 1416 …. 1732 1850 Flintham, Spring Lane 0635 0722 0740 0922 1122 1222 1422 …. 1735 1853 Screveton, Car Colston Road, Lodge Lane 0639 0726 0744 0926 1126 1226 1426 …. 1739 1857 EAST BRIDGFORD, Main Street 0647 0734 0752 0934 1134 1234 1434 …. 1747 1905 Newton, Fairway Crescent 0657 0738 0802 0938 1138 1238 1438 …. 1757 1915 Bingham, Whychwood Road …. 0745 …. 0945 1145 1245 1445 …. …. …. BINGHAM, Market Place 0702 0750 0807 0950 1150 1250 1450 …. 1802 1920 Notes: Contact: Sch - Schooldays only ML - Marshalls: 01636 821138 www.marshallscoaches.co.uk Return tickets purchased are valid on either 91 or 354 services NOT - Nottinghamshire County Council: 0115 804 4699 These services do not operate on Bank Holidays www.nottinghamshire.gov.uk/nottsbusconnect Valid from 28 September 2020 Newton Screveton Sibthorpe East Stoke Newark Service 91/354 91/354 Bingham East Flintham Elston Farndon Bridgford Bingham - East Bridgford - Elston - Newark 91/354 Monday to Saturday Operator: NOT NOT ML ML ML ML NOT NOT Service: 354 354 91A 91 91 91 354 354 Notes: Sch BINGHAM, Market Place 0600 0705 …. -

Complaints and Investigations Into Sexual Misconduct by Police Staff

Our Ref: 004392/14 Freedom of Information Section Nottinghamshire Police HQ Sherwood Lodge, Arnold Nottingham NG5 8PP Tel: 101 Ext 800 2507 Fax: 0115 967 2896 20 August 2014 Request under the Freedom of Information Act 2000 (FOIA) I write in connection with your request for information, which was received by Nottinghamshire Police on 15/07/2014. Following receipt of your request searches were conducted within Nottinghamshire Police to locate the information you require. Please find below answers to your questions:- RESPONSE Under S 1 (1) (a) of the Freedom of Information Act 2000 (FOIA), I can confirm that Nottinghamshire Police does hold the information you have requested. Under FOI laws please can you provide me with details of complaints and investigations into all forms of sexual misconduct by all employees from 2010-present, broken down by calendar year. For each incident please also specify: The nature of the offence or possible misconduct - e.g. sexual assault, inappropriate touching, rape - and the location in which the offence took place - e.g. police station. The gender of the accused employee, their role within the force and their age at the time of the incident. The gender of the alleged victim or complainant and their age at the time of the incident. The nature of the investigation (internal, criminal), whether it was referred to the IPCC and what if any disciplinary action was taken against the employee. I would also like the names of the accused in the case of a conviction, however I accept that this information may have to be redacted in some cases. -

Neighbourhood Plan?

FLINTHAM PARISH COUNCIL PARISH NEWS July 2019 The next meeting of the par- ish council takes place in the NEIGHBOURHOOD Village hall on Monday, July 8 PLAN? and it will start at 6.30pm. Arguing the case here FOR a Neighbourhood Plan for Flintham, is local All residents are welcome to parisgh cojuncillor Debra Pennington (with help from some friends!).: attend, and to take part in the Since becoming aware of the existence of Neighbourhood Plans in June 2018, I item allowing the public to have been convinced that Flintham should have one. We have some quality village participate. features; the Conservation Area, Boot and Shoe pub, active Church, the Sports Ground, Scouts Association, Primary School, Community Shop, Museum and the Syerston Airfield in our Parish, to name a few. I understand that producing the Plan is a lot of work and can take up to 2 years to complete but believe that it would serve the Community well to undertake this venture, because it crystallises the shared vision for the future development of the village both physically and culturally. There is funding and advice for undertaking a Neighbourhood Plan, such as highlighted in the presentation given by Jenny Kirkwood of Rural Community Action Nottinghamshire (RCAN) on 5th June. It is my view that the funding available will cover the total costs of the Plan given the size of our community, but we need to apply for it and who knows how long the funding will be available? Below is an extract from an email I sent to the Parish Council (PC) in June 2018 following the publication of the Rushcliffe Local Plan Part 2. -

10/02/2021 MEMBERS INTERESTS Page 1

MEMBERS INTERESTS 11/09/2021 ID SURNAME CODE PLACE NAME DATES 0014 Archbold NBL Embleton 1840 0014 Bingham NTT North Wheatley 1700 0014 Fletcher / Fruchard LND London 1700 0014 Goodenough SOM Norton St Phillip 1800 0014 Hardy NTT South Wheatley 1700 0014 Holdstock KEN Canterbury 1700 0014 Holdstock LND London 1800 0014 Lines BKM Marsworth 1800 0014 Neale HRT Barley 1700 0014 Robertson AYR Ayrshire 1800 0014 Steedman NTT North Leverton 1700 0014 Whitby CAM Arrington 1800 0014 Windmill SOM Prudsford 1800 0033 Bettney DBY Derbyshire Any 0033 Bettney NTT Nottinghamshire Any 0033 Storey GBR United Kingdom Any 0033 Twells GBR United Kingdom Any 0034 Baggaley NTT Mansfield pre 1800 0034 Quibell NTT Ragnall pre 1800 0034 Quibell NTT Darlton pre 1800 0034 Quibell NTT Nottinghamshire pre 1800 0109 Askey NTT Nottinghamshire pre 1850 0109 Askey STS Staffordshire pre 1850 0109 Beardall NTT Bestwood 1688+ 0109 Beardall NTT Hucknall 1688+ 0109 Beardall NTT Linby 1688+ 0109 Bird LEI Worthington 1857+ 0109 Butler NTT Hucknall Any 0109 Cadwallender GLS Gloucestershire pre 1850 0109 Cadwallender NTT Nottinghamshire pre 1850 0109 Camm NTT Widmerpool 1800+ 0109 Clarke NTT Linby 1750+ 0109 Fox LEI Wymeswold Any 0109 Fox NTT East Leake Any 0109 Harby NTT Nottinghamshire Any 0109 Haskey NTT Nottinghamshire pre 1850 0109 Haskey STS Staffordshire pre 1850 0109 Hayes NTT Nottinghamshire pre 1700 0109 Kem LEI Grimston pre 1800 0109 Kem NTT Widmerpool pre 1800 0109 Kirkland NTT Linby 1700+ 0109 Parnham NTT Bingham 1700+ 0109 Potter NTT Linby 1700+ 0109 Rose NTT Bulwell -

Agricultural Land for Sale Fusse Road, Screventon, Nottinghamshire, NG13 8JJ for Sale Freehold Land Guide Price: £70,000 Plus VAT Sole Selling Agents

LICENSED | LEISURE | COMMERCIAL Agricultural Land For Sale Fusse Road, Screventon, Nottinghamshire, NG13 8JJ For Sale Freehold Land Guide Price: £70,000 plus VAT Sole Selling Agents • Substantial plot of agricultural land • Situated fronting Fosse Way (A46) • Plot size amounting to circa 10.5 acres • Located adjacent to the attractive rural villages of Screveton and Flintham. • Suitable for anybody seeking land for agricultural/grazing purposes. 0113 8800 850 Second Floor, 17/19 Market Place, Wetherby, Leeds, LS22 6LQ [email protected] www.jamesabaker.co.uk Agricultural Land For Sale For Sale Freehold Land Fusse Road, Screventon, Nottinghamshire, NG13 8JJ Guide Price: £70,000 plus VAT Sole Selling Agents Location The parcel of land is situated approximately 9 miles south west of Newark-on-Trent, laying equidistant between the small villages of Screveton and Flintham. The site sits on a plot of approximately 10.5 acres (4.25 ha) and comprises solid agricultural land with shrubbery to its perimeter. The large plot is in a rural location fronting Fosse Way, the main road connecting Newark-on-Trent to Nottingham, and lays adjacent to the former Red Lodge public house - approximately 2 miles north west of central Screveton. Given the rurality of the sites location, the surrounding areas comprise predominantly fields for agricultural and grazing purposes. This site provides ideal opportunity for anybody seeking land for agricultural/grazing purposes. Total Plot Size equalling circa 10.5 acres. 0113 8800 850 Second Floor, 17/19 Market Place, Wetherby, Leeds LS22 6LQ [email protected] www.jamesabaker.co.uk Agricultural Land For Sale For Sale Freehold Land Fusse Road, Screventon, Nottinghamshire, NG13 8JJ Guide Price: £70,000 plus VAT Sole Selling Agents General Information Tenure and Possession The land is being sold freehold subject to a tenancy that falls under the Agricultural Holdings Act 1986 which commenced on the 25th March 1982. -

Nottinghamshire Aviation Memorials

Nottinghamshire Aviation Memorials Aviation | Aviation Memorials in Nottinghamshire We love to commemorate our aviation heritage. In Nottinghamshire We Love To Commemorate Our Aviation Heritage The diversity of aviation memorial locations across the county is impressive. These memorials are not just at airfield sites, but they can also be found in churches, village halls, on city streets and at remote countryside locations. Some memorials are relatively new, whilst others can trace their origins back Nottinghamshire decades. These memorials, some of them raised through public subscription, reflect the lives of national figures like Albert Ball VC; whilst others are simpler marks of respect that have been erected thanks to the efforts of small groups of individuals. There are even sculptures and pub signs that highlight the county’s contribution to the development of significant aviation technologies. Collectively they play a part in helping to commemorate the county’s aviation heritage. Many individuals had travelled from around the world to air bases in Aviation Memorials Aviation | Nottinghamshire to train as World War II bomber crews. A common bond that joins most of these memorials together is that they commemorate the lives of brave individuals who were lost whilst learning these new skills; often in difficult weather conditions, a long way from home and in a relatively congested airspace, caused by having a lot of airfields so close together. For each of the memorials listed we have provided some background information about the crews involved and the circumstances of the crash; this is merely a snapshot of incidents that are recorded in more detail in books and on websites and we would encourage you to investigate them further. -

Heritage Open Days 2016

Printable Area Lists | Heritage Open Days Page 1 of 42 Properties and events in Nottinghamshire 2016 St Giles Church - bells and more musical delights Balderton , Nottinghamshire The bells will be rung at times throughout the day by our ringers and ringers from nearby churches, we hope to ring a quarter peal at some time during the day. Groups of people will be able to visit the ringing room to watch to bells being rung. Also in the church the organ will be played at times, there will be choir singing and other musical items. Opening Times • Saturday: 1000-1800 Booking Details No booking required All Hallows Church All Hallows Church, Ordsall , Retford , Nottinghamshire, DN22 7TP There will be teas, coffees, cream teas and cakes available in church all day and the chance to see the tower which is not normally open. Opening Times • Saturday: Church 1000–1800, Tower 1300–1700 Booking Details No booking required Additional information There will be approximately 50 – 60 scarecrows in gardens around the parish, these can be viewed by anyone but maps are available showing the locations at a cost of £1 per map. Each map has a voting form attached that allows you to vote for your favourite scarecrow. The scarecrow festival is on all weekend, maps can be purchased from the local post office at any time or from the church when it is open. Attenborough Gravel Works Display by Nick Clarke Bartons plc, Barton House, 61 High Road, Chilwell, Beeston, Nottinghamshire, NG9 4AJ A display of photographs and memorabilia of Trent Gravels, which later became Ready Mixed Concrete, and latterly CEMEX of Long Lane Attenborough.