Toby Oliver ACS: ‘Beneath Hill 60’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beneath Hill 60 Free Download

BENEATH HILL 60 FREE DOWNLOAD Will Davies | 304 pages | 26 Apr 2011 | Random House Australia | 9781864711264 | English | Milsons Point, Australia Get the buzz… His unit relocated to Hill 60a notorious German stronghold in Ypres, Belgium. The main purpose was to build hospitals, underground storage and billets and if designed and built correctly with a constant supply of water and food the military could hold out against the enemy almost indefinitely. Expand the sub menu Video. A massive explosion erased the enemy position. Fletcher Illidge. Jeremy Beneath Hill 60 Director. Mild-mannered Lt. Expand the Beneath Hill 60 menu What To Watch. These were not infantrymen, but miners. Archived from the original on 28 January Windows Windows 8, Windows 8. Published June 1st by Vintage Beneath Hill 60 first published May 1st It also provides some technical details of tunnelling, which you can Beneath Hill 60 focus on or skim Beneath Hill 60 to your wont I skimmed. It us a bit all over the place and doesn't solely focus on Hill Additionally, the film displayed to the world just how big a part the Aussies played in WWI and how tremendous their sacrifice was, while also damning the way the Australians were commanded by their callous British superiors. Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Back to School Picks. For assistance, contact your corporate administrator. Jim Sneddon Alex Thompson Bella Heathcote Marjorie Waddell. May 13, Karen Burbidge rated it it was amazing. Extensive research went into developing the characters and their environment, with Canberra 's Australian War Memorial Archives providing research material. -

Gender Down Under

Issue 2015 53 Gender Down Under Edited by Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier ISSN 1613-1878 Editor About Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier Gender forum is an online, peer reviewed academic University of Cologne journal dedicated to the discussion of gender issues. As English Department an electronic journal, gender forum offers a free-of- Albertus-Magnus-Platz charge platform for the discussion of gender-related D-50923 Köln/Cologne topics in the fields of literary and cultural production, Germany media and the arts as well as politics, the natural sciences, medicine, the law, religion and philosophy. Tel +49-(0)221-470 2284 Inaugurated by Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier in 2002, the Fax +49-(0)221-470 6725 quarterly issues of the journal have focused on a email: [email protected] multitude of questions from different theoretical perspectives of feminist criticism, queer theory, and masculinity studies. gender forum also includes reviews Editorial Office and occasionally interviews, fictional pieces and poetry Laura-Marie Schnitzler, MA with a gender studies angle. Sarah Youssef, MA Christian Zeitz (General Assistant, Reviews) Opinions expressed in articles published in gender forum are those of individual authors and not necessarily Tel.: +49-(0)221-470 3030/3035 endorsed by the editors of gender forum. email: [email protected] Submissions Editorial Board Target articles should conform to current MLA Style (8th Prof. Dr. Mita Banerjee, edition) and should be between 5,000 and 8,000 words in Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (Germany) length. Please make sure to number your paragraphs Prof. Dr. Nilufer E. Bharucha, and include a bio-blurb and an abstract of roughly 300 University of Mumbai (India) words. -

Opportunities

TOWNSVILLE NORTH QUEENSLAND REPORT ON FILM INDUSTRY OPPORTUNITIES TOWNSVILLE NORTH QUEENSLAND REPORT ON OPPORTUNITIES July 2015 1 TOWNSVILLE NORTH QUEENSLAND REPORT ON FILM INDUSTRY OPPORTUNITIES TABLE OF CONTENTS BACKGROUND AND EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 TOWNSVILLE – A UNIQUE LOCATION 4 COORDINATION 5 COUNCIL ADMINISTRATION 5 COLLABORATION 5 KEY STAKEHOLDERS 5 Government 6 Education Facilities 7 Economic and Tourism Bodies 8 CULTURAL / THEMATIC TOURISM / FILM FESTIVALS 9 SUPPORT 10 INDUSTRY RESOURCES 10 Locations Gallery 10 SERVICE AND RESOURCE DIRECTORY 11 INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT 12 GROWTH 13 INDUSTRY DEVELOPMENT 13 Industry Incentives, Grants and Funding 13 Development of a Film, Television and New Media Fund 13 Industry Development Body 13 Singapore Media Development Authority 14 Georgia Film Tax Offset 14 Local Townsville Industry Contacts 15 SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS 16 REFERENCES 17 APPENDIX 1 18 SUBMISSION BY BILL LEIMBACH APPENDIX 2 21 SUMMARY OF INCENTIVES AND FUNDING MODELS Federal Government Funding 21 State Based Funding 21 Queensland 21 Victoria 22 South Australia 22 USA - THE GEORGIA ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY INVESTMENT ACT 23 2 TOWNSVILLE NORTH QUEENSLAND REPORT ON FILM INDUSTRY OPPORTUNITIES BACKGROUND AND EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Townsville City Council and James Cook University have undertaken Townsville offers the film and television industry unique, diverse a research partnership in 2014 and 2015 involving a detailed analysis and accessible locations in an affordable and film-friendly place. of the current and future employment -

Beneath Hill 60: the Australian Miners’ Secret Warfare Beneath the Trenches of the Western Front

Jump TO Article The article on the pages below is reprinted by permission from United Service (the journal of the Royal United Services Institute of New South Wales), which seeks to inform the defence and security debate in Australia and to bring an Australian perspective to that debate internationally. The Royal United Services Institute of New South Wales (RUSI NSW) has been promoting informed debate on defence and security issues since 1888. To receive quarterly copies of United Service and to obtain other significant benefits of RUSI NSW membership, please see our online Membership page: www.rusinsw.org.au/Membership Jump TO Article BOOK REVIEW Beneath Hill 60: the Australian miners’ secret warfare beneath the trenches of the Western Front by Will Davies Vintage Books: North Sydney; 2010; 272 pp.; ISBN 978 1 74166 936 7; RRP $18.95 (paperback); Ursula Davidson Library call number 570.2 DAVI 2010 Many readers will have seen the film, Beneath Hill 60: The book, like the film, tends to focus on the The Silent War, a largely fictionalised account of the deeds of the section of the 1st Australian Tunnelling deeds of the 1st Australian Tunnelling Company in Company led by Captain Oliver Woodward, MC**, as it is Flanders in 1916 and 1917. Readers may also be Woodward’s unpublished diaries that provide much of familiar with previous work by Will Davies, in particular the evidence on which the book is based. Interestingly, Somme Mud1, the diaries of Private E. P. F. Lynch, which Woodward received his baptism of fire, not as a he edited. -

Sweet Country

Presents SWEET COUNTRY Directed by Warwick Thornton / In cinemas 25 January 2018 Starring HAMILTON MORRIS, BRYAN BROWN and SAM NEILL PUBLICITY REQUESTS: TM Publicity / Tracey Mair / +61 2 8333 9066 / [email protected] IMAGES High res images and poster available to download via the DOWNLOAD MEDIA tab at: http://www.transmissionfilms.com.au/films/sweet-country Distributed in Australia by Transmission Films SWEET COUNTRY is produced by Bunya Productions, with major production investment and development support from Screen Australia’s Indigenous Department, in association with the South Australian Film Corporation, Create NSW, Screen Territory and the Adelaide Film Festival. International sales are being handled by Memento and the Australian release by Transmission Films. © 2017 Retroflex Lateral Pty Ltd, Screen NSW, South Australian Film Corporation, Adelaide Film Festival and Screen Australia SHORT SYNOPSIS Inspired by real events, Sweet Country is a period western set in 1929 in the outback of the Northern Territory, Australia. When Aboriginal stockman Sam (Hamilton Morris) kills white station owner Harry March (Ewen Leslie) in self- defence, Sam and his wife Lizzie (Natassia Gorey-Furber) go on the run. They are pursued across the outback, through glorious but harsh desert country. Sergeant Fletcher (Bryan Brown) leads the posse with the help of Aboriginal tracker Archie (Gibson John) and local landowners Fred Smith (Sam Neill) and Mick Kennedy (Thomas M. Wright). Fletcher is desperate to capture Sam and put him on trial for murder – but Sam is an expert bushman and he has little difficulty outlasting them. Eventually, for the health of his pregnant wife, Sam decides to give himself up. -

5Th AACTA Awards Nominations Announced

MEDIA RELEASE Strictly embargoed until 6am Thursday 29 October 2015 BOX OFFICE SUCCESS BOLSTERED BY AACTA AWARD NOMINATIONS FOR AUSTRALIA’S TOP FILMS OF 2015 Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts (AACTA) announces Feature Film, Television, Visual Effects or Animation and remaining Documentary nominations for the 5th AACTA Awards presented by Presto. SYDNEY - In a year of record box office success for Australian films, taking more than $65 million locally to date, speculation about which films would be nominated for Australia’s top screen Awards has been buzzing. Today the wait is over, with AACTA announcing that a total of 11 Australian feature films have received nominations. The five vying for the coveted AACTA Award for Best Film Presented by Presto are: THE DRESSMAKER, a comedic drama celebrating revenge and setting wrongs right in 1950s Australia; HOLDING THE MAN, a funny yet heart-breaking story of two men in love despite the height of 1980s prejudice; LAST CAB TO DARWIN, an uplifting drama about a dying man which shows it’s never too late to start living; MAD MAX: FURY ROAD, seeing the MAD MAX juggernaut continue with an explosive post-apocalyptic Road War; and PAPER PLANES, the story of a young boy’s Quest to compete in the World Paper Plane Championships. AACTA today also announced that a total of 31 television productions have received nominations for the 5th AACTA Awards presented by Presto, with PETER ALLEN – NOT THE BOY NEXT DOOR (Seven Network), DEADLINE GALLIPOLI (FOXTEL - Showcase), THE SECRET RIVER (ABC), REDFERN NOW – PROMISE ME (ABC) and BANISHED (FOXTEL - BBC First) making the top-five most nominated productions. -

CINEMA in AUSTRALIA an Industry Profile CINEMA in AUSTRALIA: an INDUSTRY PROFILE

CINEMA IN AUSTRALIA an industry profile CINEMA IN AUSTRALIA: AN INDUSTRY PROFILE Acknowledgments Spreading Fictions: Distributing Stories in the Online Age is a three-year Australian Research Council funded Linkage Project [LP100200656] supported by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) and Screen Australia. The chief investigators are Jock Given, Professor of Media and Communications, The Swinburne Institute for Social Research, Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne and Gerard Goggin, Professor of Media and Communications, The University of Sydney. Partner Investigators: Georgie McClean, Manager, Strategy and Research, Screen Australia Michael Brealey, Head of Strategy and Governance, ABC TV This report was researched and written by Jock Given, Rosemary Curtis and Marion McCutcheon. Many thanks to the ABC, Screen Australia and the Australian Research Council for their generous support of the project and to the following organisations for assistance with this report: Australian Film Television and Radio School Library Independent Cinemas Association of Australia [ICAA] IHS Screen Digest Motion Picture Distributors Association of Australia [MPDAA] National Association of Cinema Operators-Australasia [NACO] Rentrak Roy Morgan Research Val Morgan Cinema Network Any views expressed in this report are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Industry Partners or other organisations. Publication editing and design: Screen Australia Published by The Swinburne Institute, Swinburne University of Technology, PO Box 218 -

9-1 Trenches and Battles

Flanders and northern France: Britain declared war on Germany on August 4th 1914 when Germany invaded France through Belgium. The British government sent the B.E.F (British Expeditionary Force) to northern France to try and stop the German advance. The BEF had 70,000 professional soldiers fighting alongside the French army. After the initial fighting, both the British and Germans pulled back their forces and ‘dug in’ creating miles of trenches. This is when ‘Trench Warfare’ began… A defensive approach to fighting whereby soldiers defend their trenches with some attempts to capture Attrition / Stalemate: the enemy trenches usually failing or at great loss for a small gain. Features of the Trench System: Feature 1: Design Trenches were first dug by the British and French Armies in Northern France during the race to the sea. The aim of trenches was to act as a barrier against the rapid advance of the German army from which a counter attack could be made. At first they were quickly and easily constructed using few materials other than sandbags and a shovel. They were meant to be temporary and everyone expected a war of movement in 1915. The trenches became where most of the war was fought, because of the stalemate. It was so dangerous to come out of the trench. As the trenches got more complex and weapons such as gas, tanks and aeroplanes improved, it became harder to break through. Describe 2 features of the Trench design [4] Stick your trench diagram into the middle of 2 pages and describe a feature of each part of the trench system in detail. -

HAYWOOD Chris

SHANAHAN CHRIS HAYWOOD | Actor FILM Year Production / Character Director Company 2018 DIRT MUSIC Gregor Jordan Wildgaze Films Warwick 2017 AUSTRALIA DAY Kriv Stenders Hoodlum Entertainment Dr. Norris 2015 BOAR Chris Sun Pig Enterprises Pty Ltd Jack 2014 TRUTH James Vanderbilt FEA Productions Pty Ltd Bill Hollowell 2014 LOVE IS NOW Jim Lounsbury Eponine Films Ben 2012 NIM’S ISLAND 2 Brendan Maher Nim’s Productions P/L. Grant 2012 ALMAYER’S FOLLY U-Wei Haji Saari Tanah Licin Sdn Bhd Captain Ford 2011 PALAWAN FATE Auraeus Solito Cinemalaya Foundation Landowner 2011 SWERVE Craig Lahiff Duo Art Productions Armstrong 2011 SLEEPING BEAUTY Julia Leigh Sleeping Beauty Productions Man 2 2010 HELL’S GATE Noise & Light Pty Ltd Old Soldier 2009 BENEATH HILL 60 Jeremy Sims The Silence Productions Colonel Rutledge Shanahan Management Pty Ltd PO Box 1509 | Darlinghurst NSW 1300 Australia | ABN 46 001 117 728 Telephone 61 2 8202 1800 | Facsimile 61 2 8202 1801 | [email protected] SHANAHAN 2009 SAVAGES CROSSING Kevin James Dobson Show Film Chris 2009 REINCARNATION OF WILLIAM Malcolm McDonald December Films BUCKLEY John Morgan 2008 BOYS ARE BACK IN TOWN Scott Hicks SLF Boys Production P/L Tom 2008 THE LAST CONFESSION OF Michael James Rowland Essential Viewing ALEXANDER PEARCE Knopwood 2007 RETURN TO GREENHAVEN DRIVE The McCrae Brothers Screentime Dashiell 2006 SALVATION Paul Cox Illumination Films Architect 2006 THE BRIDGE John Gaeta 21st Century Productions Tokyo Dr Hecks 2005 SOLO Morgan O’Neill Screentime Pty Ltd/Project Greenlight Arkan 2005 JINDABYNE -

Modern Australian Anzac Cinema

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Avondale College: ResearchOnline@Avondale Avondale College ResearchOnline@Avondale Arts Book Chapters School of Humanities and Creative Arts 2014 National Versions of the Great War: Modern Australian Anzac Cinema Daniel Reynaud Avondale College of Higher Education, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://research.avondale.edu.au/arts_chapters Part of the Other Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Other History Commons Recommended Citation Reynaud, D. (2014). National versions of the Great War: Modern Australian Anzac cinema. In M. Loschnigg & M. Sokolowska-Paryz (Eds.), The Great War in post-memory literature and film (pp. 289-304). Berlin, Germany: De Gruyter. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Humanities and Creative Arts at ResearchOnline@Avondale. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts Book Chapters by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@Avondale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Daniel Reynaud National Versions of the Great War: Modern Australian Anzac Cinema 1 The Anzac Legend as National Narrative While many nations generated myths of loss and tragedy from the Great War, Australia has forged a positive myth of identity, built on the national narrative of the Anzac legend which encapsulates what it means to be truly Australian (cf. Seal 6–9). The Anzac story has become seminal to the Australian identity since the landing of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) at Gallipoli on 25 April 1915. -

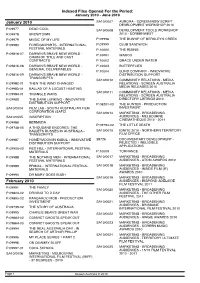

Current Filelist V2

Indexed Files Opened For the Period: January 2010 - June 2010 January 2010 SA10/0007 AURORA - SCREEN NSW SCRIPT DEVELOPMENT WORKSHOP 2010 P.09977 DEAD COOL SA10/0008 DEVELOPMENT TOOLS WORKSHOP P.09978 SNOWTOWN 2010 - SCREENWEST P.09979 MUSIC OF MY LIFE P.09998 THE BUNYIP OF BERKLEY'S CREEK P.09980 FOREIGN PARTS - INTERNATIONAL P.09999 CLUB SANDWICH FESTIVAL MATERIALS P.10000 THE RISING P.09816-07 DARWIN'S BRAVE NEW WORLD - P.10001 WARCO CHAIN OF TITLE AND CAST CONTRACTS P.10002 GRACE UNDER WATER P.09816-08 DARWIN'S BRAVE NEW WORLD - P.10003 BUTTERFLIES GENERAL DELIVERABLES P.10004 BLIND COMPANY - INNOVATIVE P.09816-09 DARWIN'S BRAVE NEW WORLD - DISTRIBUTION SUPPORT TRANSCRIPTS SA10/0010 COMMUNITY RELATIONS - MEDIA P.09982-01 THEN THE WIND CHANGED RELATIONS - SCREEN AUSTRALIA MEDIA RELEASES 2010 P.09983-01 BALLAD OF A LOCUST HUNTING SA10/0011 COMMUNITY RELATIONS - MEDIA P.09984-01 TRIANGLE WARS RELATIONS - SCREEN AUSTRALIA P.09985 THE DARK LURKING - INNOVATIVE DIRECTORY LISTINGS 2010 DISTRIBUTION SUPPORT P.08201-03 THE HUNTER - PRODUCTION SA10/0004 FILM LAB - SOUTH AUSTRALIAN FILM INVESTMENT CORPORATION (SAFC) SA10/0014 MARKETING - BROADENING SA10/0005 INSCRIPTION AUDIENCES - MELBOURNE CINEMATHEQUE 2010 - 2011 P.09986 BERMUDA P.09794-02 THE LITTLE DEATH P.09748-05 A THOUSAND ENCORES: THE BALLETS RUSSES IN AUSTRALIA - SA10/0015 IGNITE 2010 - NORTHERN TERRITORY TRANSCRIPTS FILM OFFICE P.09987 HONEYMOON IN KABUL - INNOVATIVE 38726 DOCUMENTARY DEVELOPMENT - DISTRIBUTION SUPPORT REJECTED / INELIGIBLE APPLICATIONS P.09905-02 RED HILL - INTERNATIONAL -

HI 408 War in Film and Literature

HI 408 War in Film and Literature Cathal J. Nolan Associate Professor of History Executive Director, International History Institute Combat, killing, suffering, death. This course explores these vivid human experiences through great, and lesser, works of film and literature. Topics range widely, from medieval Japan to Africa, the Americas and Europe, the two 20th century world wars and various Asmall wars@ of the 19th through 21st centuries. We explore "the angle of vision" problem: who should we trust more, eye-witness accounts of war, great poets and novelists, modern film-makers, or military and other historians? Who gets us closest to the "truth" about war as a fundamental element of the human experience and condition? Can we draw general conclusions about the experience of war? Or do we falsely impose our own ideas on history? Note: The course is thematic rather than narrative. Some of you will likely find it necessary to do additional reading on the general history of war (Allure of Battle is assigned to this end), and reading that situates specific wars in overarching patterns of military history. I will provide guidance in class and to those who ask for it outside class. Consult the course site on Blackboard, where there are many additional features, from photos and music files to videos, to still and animated maps. Administrative Information Office hours: Monday and Tuesday, 630-800 pm. Location: B-13, 725 Commonwealth Avenue. Phone: (617) 353-1165 e-mail: [email protected] Email is best method of contact. Participation 20% Required: unexcused absences will reduce final grade Film Review (6p) 20% February 23 Film Review (6p) 20% March 19 Term Paper (15-18p) 40% April 23 See the guide to the term paper posted online.