Music, Memory and Faith

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020-21 Parish School of Religion Begins Tuesday!

Page 311 South 5th Street, Colwich KS 67030 | Twenty-First Sunday in Ordinary Time - August 23, 2020 PSR Families! There will be a meeting & open house, TODAY, August 23rd after the 10 am Mass in Sacred Heart Hall. You will be given valuable information & your child will be able to meet their teacher. Please plan on attending. 2020-21 PARISH SCHOOL OF RELIGION BEGINS TUESDAY! If you have not yet registered for PSR please contact the office & do so as soon as possible. Please be aware! Per the Renwick School District, busses will be dropping off students at the school and they will need to cross the street to the church grounds. 2020 CONFIRMATION Confirmation Classes resume August 26th. All Confirmation students & their parents are asked to come to a meeting & social in Sacred Heart Hall, Wed, August 26th after the 6:30 pm Mass. Please plan on attending. BLOOD DRIVE Monday, August 24th | Noon-6:00 pm Register online at redcrossblood.org or through our website. Questions? Contact Karla Neville at 796-1422. ROSARY CRUSADE We are saying the rosary as a parish family each evening at 7:30 pm in front of the Sacred Heart Statue. Leaders are needed. Please visit our website to sign-up. (Rosaries & pamphlets on how to say the rosary are available in the Gathering Space.) OFFICE STAFF Pastor Parish Life Coordinator Fr. Eric Weldon [email protected] Jillian Linnebur [email protected] Secretary Bookkeeper Julie Bardon [email protected] Kathy Seltenreich [email protected] MASS TIMES CONFESSIONS Weekend Weekdays Weekdays 15 Minutes before Mass Saturday 4:30 PM All Weekdays 8:00 AM Saturdays 3:00 - 4:00 PM Sunday 8:00 AM & 10:00 AM And by Appointment HOLY DAYS OF OBLIGATION Vigil 6:30 PM Day Of 7:30 AM & 6:30 PM WWW.SACREDHEARTCOLWICH.ORG [email protected] Phone Number: 316-796-1224 Emergency Number: 316-796-1224 x 9 311 S 5th St, P O Box 578 Colwich, KS 67030 Office Hours: Weekdays, 9 am - Noon | Welcome to Sacred Heart Catholic Church Page 2 Thoughts from Fr. -

Sacred Music Volume 112 Number 3

Volume 112, Number 3 SACRED MUSIC (Fall) 1985 St. Cecile of Montserrat, Spain SACRED MUSIC Volume 112, Number 3, Fall 1985 FROM THE EDITORS The Fabric of the Catholic Faith 3 Pope John Paul and Von Karajan Make a Point 4 PROGRAM: VIII INTERNATIONAL CHURCH MUSIC CONGRESS 6 MOZART IN SAINT PETER'S Reverend Richard M. Hogan 7 INAUGURAL ADDRESS: GREGORIAN CHANT CONGRESS Dom Jean Claire, O.S.B. 11 BALTIMORE: CATHOLICITY IN THE EARLY YEARS /. Vincent Higginson 19 WHAT IS CORRECT IN CHURCH MUSIC? 24 REVIEWS 27 NEWS 30 CONTRIBUTORS 31 EDITORIAL NOTES 31 SACRED MUSIC Continuation of Caecilia, published by the Society of St. Caecilia since 1874, and The Catholic Choirmaster, published by the Society of St. Gregory of America since 1915. Published quarterly by the Church Music Association of America. Office of publications: 548 Lafond Avenue, Saint Paul, Minnesota 55103. Editorial Board: Rev. Msgr. Richard J. Schuler, Editor Rev. Ralph S. March, S.O. Cist. Rev. John Buchanan Harold Hughesdon William P. Mahrt Virginia A. Schubert Cal Stepan Rev. Richard M. Hogan Mary Ellen Strapp Judy Labon News: Rev. Msgr. Richard J. Schuler 548 Lafond Avenue, Saint Paul, Minnesota 55103 Music for Review: Paul Salamunovich, 10828 Valley Spring Lane, N. Hollywood, Calif. 91602 Rev. Ralph S. March, S.O. Cist., Eintrachstrasse 166, D-5000 Koln 1, West Germany Paul Manz, 1700 E. 56th St., Chicago, Illinois 60637 Membership, Circulation and Advertising: 548 Lafond Avenue, Saint Paul, Minnesota 55103 CHURCH MUSIC ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA Officers and Board of Directors President Monsignor Richard J. Schuler Vice-President Gerhard Track General Secretary Virginia A. -

Rosary for Peace

Afor theRosary national day offor prayer • januaryPeace 1, 2002 Introduction She is the dawn of peace shining in the darkness n the summer of 1915, the vicious brutality of of a world out of joint; she never ceases to the “war to end all wars” had enshrouded the implore her Son for peace although his hour is hill towns of Italy and the streets of Rome. By not yet come (cf. Jn 2:4); she always intervenes I the time Pope Benedict XV had celebrated the on behalf of sorrowing humanity in the hour of Solemnity of Saints Peter and Paul, sixty thou- danger; today she who is the mother of many sand mothers had buried their sons; while later that orphans and our advocate in this tremendous same year, as he led the Church in commemorating catastrophe will most quickly hear our prayers. the feast of the Immaculate Conception, that number had reached a quarter of a million. The day after the horrors of September 11, 2001, Pope John Paul II responded with a prayer to “the Blessed Thus, amidst the fear and uncertainty of a dark Virgin, Mother of Mercy, [to] fill the hearts of all Christmas Eve, the Holy Father gathered his cardinals with wise thoughts and peaceful intentions.”1 Such a together to announce a plan for peace. His plan first reaction is expected in one who has repeatedly would marshal an army of prayers who would storm urged us to seek the intercession of the Blessed Virgin heaven with petitions to “the Mother of the Prince of Mary, under the title “Queen of Peace.” Seven years Peace, Mediatrix between rebellious man and the ago, on the Solemnity of the Immaculate Conception, merciful God.” Confident that “with God all things the Holy Father urged all who would be peace makers are possible,” Pope Benedict XV inserted the name of to look to the example of the Blessed Virgin: “Queen of Peace” into the Marian Litany of Loreto. -

Marian Devotions Booklet.Pdf

Index Veneration of the Holy Mother of God ............................................ 1 How to Pray the Rosary ..................................................................... 3 Mysteries of the Rosary ...................................................................... 5 Prayers of the Rosary .......................................................................... 7 Angelus ................................................................................................... 9 Queen of Heaven/ Regina Coeli .........................................................11 Litany of Loreto ....................................................................................12 Memorare ................................................................................................ 13 Salve Regina............................................................................................ 15 Marian Medals ......................................................................................17 Immaculate Mary .................................................................................19 Hail Holy Queen .................................................................................. 19 Devotion to the Seven Sorrows of Mary ...........................................21 Virgin of Guadalupe ............................................................................23 Sacred Scripture: The Holy Bible translated by Msgr. Ronald Knox Our Lady of La Vang ...........................................................................23 Copyright -

Worship the Lord

St. John the Beloved Catholic Church in McLean, Virginia May 9, 2021 Worship the Lord Mass Intentions Remember in Prayer Monday, May 10 Patricia Ahern Richard Meade St. Damien de Veuster, Priest Frank Bohan Diana Meisel 6:30 Eleanor Sampey † Carmel Broadfoot Bonnie Moran 9:00 Mother’s Day Novena John Cartelli Veronica Nowakowski 8:00 Greg Wood Edward Ciesielski Anita Oliveira Tuesday, May 11 Victoria Grace Czarniecki Emelinda Oliveira Easter Weekday Kerry Darby John Peterson 6:30 Victor Hugo † Tara Flanagan-Koenig Mary Pistorino Reilly 9:00 Mother’s Day Novena Alexa Frisbie Shelby Rogers Inés Garcia Robles Thomas Rosa Wednesday, May 12 Susan Glover Paul Ruggera Sts. Nereus and Achilleus, Martyrs; St. Pancras, Martyr Francisca Grego Murielle Rozier-Francoville 6:30 Dick De Corps † Arnold L. Harrington III Avery Schaeffer 9:00 Mother’s Day Novena Colleen Hodgdon Merle Shannon Thursday, May 13 David Johnson Fred Sheridan Easter Weekday Mark Johnson Gloribeth Smith 6:30 Philomena O’Connell † Christopher Katz Glenn Snyder 7:30 Low Mass Margaret Kemp Bill Sullivan 9:00 Mother’s Day Novena Dorothy Kottler Ana Vera Sue Malone Mary Warchot Friday, May 14 Carmella Manetti Marie Wysolmerski St. Matthias, Apostle Cristina Marques 6:30 Ian G. McIntyre † 9:00 Mother’s Day Novena May God bless and protect our loved ones in the Saturday, May 15 military and civil service who are serving these St. Isadore United States in dangerous places, especially... 8:15 Mother’s Day Novena 5:00 Victor Hugo † Robert Ayala Blair Smolar Jonathan Choo Michael Shipley -

Divine Worship Newsletter

ARCHDIOCESE OF PORTLAND IN OREGON Divine Worship Newsletter Crucifix, Ampleforth Abbey, Yorkshire England ISSUE 33 - JULY 2020 Welcome to the thirty-third Monthly Newsletter of the Office of Divine Worship of the Archdiocese of Portland in Oregon. We hope to provide news with regard to liturgical topics and events of interest to those in the Archdiocese who have a pastoral role that involves the Sacred Liturgy. The hope is that the priests of the Archdiocese will take a glance at this newsletter and share it with those in their parishes that are involved or interested in the Sacred Liturgy. This Newsletter is now available through Apple Books and always available in pdf format on the Archdiocesan website. It will also be included in the weekly priests’ mailing. If you would like to be emailed a copy of this newsletter as soon as it is published please send your email address to Anne Marie Van Dyke at [email protected]. Just put DWNL in the subject field and we will add you to the mailing list. All past issues of the DWNL are available on the Divine Worship Webpage and from Apple Books. An index of all the articles in past issues is also available on our webpage. The answer to last month’s competition was: Joan Lewis - the first correct answer was submitted by Rita Francis of Our Lady of Fatima Parish in Shady Cove, OR. If you have a topic that you would like to see explained or addressed in this newsletter please feel free to email this office and we will try to answer your questions and address topics that interest you and others who are concerned with Sacred Liturgy in the Archdiocese. -

Hail Mary Hail Mary, Full of Grace, % Glue the Prayers and Images Onto the Banner

The Story of Mary These moments in Mary’s life offer us the opportunity to learn from her and emulate her response to God. Mary teaches us how to lead our lives in faith and hope and love. ary was a young Jewish woman who lived in Nazareth in what is now Israel. The early traditions of the Christian community named Mary’s parents Anne and Joachim. Because of Mary’s Mfaithfulness as a Jewish woman, we can imagine that her parents were also devout Jews and raised their daughter in accordance with their faith. Their tender care and devotion helped Mary to grow into the confident, yet humble young woman who would say yes to God. Because of the time and area in which Mary lived, we can make some pretty good guesses about what her life was like. Mary was probably a peasant. Life in a rural village of the Middle East such as Nazareth would have been filled with hard work. Most women and many men were illiterate. During this time period, Mary’s homeland was occupied by the Romans. It was a difficult life under Roman rule, filled with violence and poverty. The Jews looked for a Messiah who would liberate them from the oppressive rule of Caesar. Mary notes the injustice of the world around her in her Magnificat when she recalls God’s promise to “[throw] down the rulers from their thrones, but [lift] up the lowly.” (Luke :46–55) As a woman deeply rooted in the Jewish faith, Mary trusted that God heard the cries of his people and would “remember his mercy.” (Luke :54) Too often we forget that Mary and Jesus were Jews. -

Mary for the Third Millennium - Part 7 of 8 - Woman of Israel-Daughter of Zion

Mary for the Third Millennium - Part 7 of 8 - Woman of Israel-Daughter of Zion Introduction The Litany of the Blessed Virgin Mary is a Marian litany originally approved in 1587 by Sixtus V. It is also known as the Litany of Loreto, for its first-known place of origin, the Shrine of Our Lady of Loreto (Italy), where its usage was recorded as early as 1558. Much of what it said of Mary originates in the Older Testament. Mary can be perceived in the shadow of the persons and institutions of the Old Testament. Abraham’s faith constitutes the beginning of the Old Covenant; Mary’s faith at the Annunciation inaugurates the New Covenant. (Redemptoris Mater, #14). The linking of both Covenants is found in Vatican II’s Dei Verbum – “God, who is the author of all the books of the Old Testament and New Teatament, in his wisdom and providence has brought it about that the New should be hidden in the Old and that the Old should be made clear in the New” (DV #16). The Newer Testament texts we have portray Mary in Older Testament images; see how Luke takes the Canticle of Hannah (II Samuel 2:1-14), mother of Samuel, to form Mary’s Magnificat (Luke 1:46-55). Luke takes the faith-filled personalities of the Old Testament and the themes that reflect God’s work in Israel’s saving history, and weaves them into stories that show Mary as the fulfilment of these themes, images, and persons. The infancy narratives that begin Matthew and Luke use Old Testament texts to interpret a new situation; the intention is not to explain the original text, but to make it relevant to a present set of circumstances. -

2020-08-16.Pdf

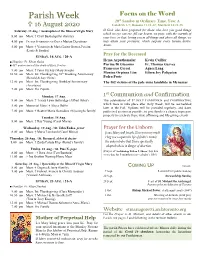

Focus on the Word Parish Week 20th Sunday in Ordinary Time, Year A 16 August 2020 Isaiah 56.1-7; Romans 11.13-32; Matthew 15.21-28 Saturday, 15 Aug. / Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary O God, who have prepared for those who love you good things which no eye can see, fill our hearts, we pray, with the warmth of 8.00 am Mass: † Cyril Bastiampillai (family) your love, so that, loving you in all things and above all things, we 4.00 pm FATIMA SCARBOROUGH GROUP Marian Devotions may attain your promises, which surpass every human desire. Amen. 5.00 pm Mass: † Venancio & Maria Luiza Gomes-Pereira (Louis & Sandra) Pray for the Deceased SUNDAY, 16 AUG. / 20-A ■ Homilist: Fr. Edwin Galea Hema Arputhamalar Kevin Caillier ■ 43rd anniversary of the death of Elvis Presley Pierina Di Giacomo Fr. Thomas Garvey Francesco Geraci Agnes Lang 9.00 am Mass: † Peter Pitchay (Mary Joseph) 10.30 am Mass: Int. Thanksgiving 38th Wedding Anniversary Monina Orpiana Lim Eileen Joy Paligutan Pedro Porte (Ronald & Jane Pinto) 12.00 pm Mass: Int. Thanksgiving Birthday/Anniversary The 162 victims of the jade mine landslide in Mynamar (Anastasia) 7.00 pm Mass: Pro Populo 1st Communion and Confirmation Monday, 17 Aug. 8.00 am Mass: † Tracey Lynn Betteridge (Alfred Haley) The celebrations of 1st HOLY COMMUNION and CONFIRMATION, which were to take place after Holy Week, will be rescheduled 5.00 pm Memorial Mass: † Alicia Delfin later in the Fall. Updates will be provided regularly, and dates 7.00 pm Mass: † Beatriz Maria Remedios (Wijesinghe family) publicized as soon as possible, to give families a chance to prepare properly to celebrate these vital, affirming and life-giving events Tuesday, 18 Aug. -

VAULT BX 2080. A2 1470 Book of Hours (Use of Rome) with Added Prayers and Marian Litanies Venice XV3/4

Manuscript description by Brittany Rancour VAULT BX 2080. A2 1470 Book of Hours (Use of Rome) with added prayers and Marian litanies Venice XV3/4 CONTENT Calendar (ff. 1r1-9v), Added Prayer (f.10r1-10r12), The Hours of the Blessed Virgin (ff. 10v1- 122v10), Office of the Dead (ff. 123r1-223v5), Seven Penitential Psalms (ff. 224r1-244v9), Litanies (ff. 245r1-256v10), Prayers (ff. 257r1-260v3), Office of the Holy Cross (ff. 260v4- 267r5), Added Text and Indulgence Prayer (ff. 267r6-270v5), Office of the Glorious Virgin (ff. 271r1-294r5), Marian Litany (ff. 294r6-322r11), Prayers in Italian (ff. 322v1-330r11). MODERN EDITIONS Medievalist.net. “A Hypertext Book of Hours.” http://medievalist.net/hourstxt/home.htm. PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION Parchment. 330 folios. Multiple scribes. I6 (wants 1, 2,6), II8 (wants final folio), III8 (wants 1), IV-XXXV8, XXXVI4 (one leaf missing between XXXV and XXXVI), XXXVII10 (beginning of added section), XLIII10. Quire signatures in single initials with four surrounding dots begins after the calendar (f.18v). Only five folia appear to be missing (likely the most elaborately decorated). HF’ FH. Bound s. XVIII. Dimensions of book 9.5 cm X 7.7 cm. Dimensions of folio 9.2 cm X 6.5 cm. 4 cm X 5.2 cm. 10 long lines, not ruled (format changes to 9 long lines 268v-269v and to 11 long lines 271r for the rest of the text). Gothic Textura-formal Grade. Text varies from brown to very black. Some marginal gloss. Rubricated titles and frequent rubrication throughout. Decorated initials in either red with blue linear/floral penwork or blue with red linear/floral penwork. -

Christian Prayer: Relationship with God, Personal and Communal; Listening, Responding to God’S Spirit

RELIGIOUS EDUCATION UNIT OVERVIEW This overview is offered for support and reference only. It is presented with recognition that all teachers apply professional skills and and judgement in response to differing levels of student knowledge and need. Teacher’s Name Years 3 and 4 (Thread A of A,B cycle) Time GNfL Element: Christian Prayer: Relationship with God, personal and communal; Listening, responding to God’s Spirit Year Level Focus: The Liturgy of the Church expresses our loving relationship with God and helps people live like Jesus Unit Content Statement: Students will be invited to deepen their relationship with God and with others through prayer, both personal and communal. As individuals and in community they will have opportunities to explore different kinds of prayer and to be involved in different prayer experiences. They will investigate the Liturgical Cycle of the Seasons of the Church Year, a pattern linked to the life, death and resurrection of Jesus. Students will explore the basic elements of Liturgy and be introduced to the Eucharist as the celebration at the heart of Christian prayer and life. T hey will explore how we honour Mary through prayers, the Hail Mary, Angelus and Rosary in particular, and through the celebration of feasts days within the liturgical calendar. Element Core Doctrinal Concepts Catechism Reference Suggested Related Scripture References Christian Prayer 1. People celebrate and pray together at different times and in different ways 2660, 2691 Extracts from chosen psalms, e.g. Ps 61: 4-5 Prayer for loving care Ps 147:1-5- Sing and Praise the Lord Ps 105:1-3 – The Lord Can be Trusted 2. -

The Holy Bible Translated by Msgr. Ronald Knox Copyright Sheed & Ward, Inc., New York, 1950

Sacred Scripture: The Holy Bible translated by Msgr. Ronald Knox Copyright Sheed & Ward, Inc., New York, 1950. Cover: The Madonna of the Burning Bush; Georges Trubert, Book of Hours, c. 1480, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Veneration of the Holy Mother of God Popular devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary is an important and universal ecclesial phenomenon. Its expressions are multifarious and its motivation very profound, deriving as it does from the People of God’s faith in, and love for, Christ, the Redeemer of mankind, and from an awareness of the salvific mission that God entrusted to Mary of Nazareth, because of which she is Mother not only of Our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ, but also of mankind in the order of grace. Indeed, the faithful easily understand the vital link uniting Son and Mother. They realize that the Son is God and that she, the Mother, is also their mother. They intuit the immaculate holiness of the Blessed Virgin Mary, and in venerating her as the glorious queen of Heaven, they are absolutely certain that she who is full of mercy intercedes for them. Hence, they confidently have recourse to her patronage. The poorest of the poor feel especially close to her. They know that she, like them, was poor, and greatly suffered in meekness and patience. They can identify with her suffering at the crucifixion and death of her Son, as well as rejoice with her in his resurrection. The faithful joyfully celebrate her feasts, make pilgrimage to her sanctuary, sing hymns in her honor, and make votive offerings to her.