Reconnecting with Laurie Baker by ZIYA US SALAM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Making of an Energy Analyst: Some Personal Reflections

THE MAKING OF AN ENERGY ANALYST: SOME PERSONAL REFLECTIONS Amulya K.N. Reddy International Energy Initiative 25/5 Borebank Road, Benson Town, Bangalore 560046, India [Tel/Fax: +91-80-353 8426 (office) +91-80-334 6234 (home)] [email: [email protected]] Running Head: Making of an Energy Analyst Key words: energy analysis, energy planning, energy consumption patterns, global energy, rural energy, rural technology 1 Introduction (1) I was born in 1930 in the South Indian city of Bangalore, which was then known as a pensioners' paradise and as a garden city with its greenery and parks. Its climate was salubrious and I never saw a ceiling fan until I was in my teens. I used to walk a couple of miles to school through the center of town, without my parents fearing that I would be run over. Today, Bangalore is the IT capital of India, choked with vehicular traffic and highly polluted. Bangalore always had excellent schools and colleges. I did my schooling in a Jesuit institution, St. Joseph's, with the motto: Faith and Toil. There, I was fortunate in having an outstanding and inspiring science teacher, Alec Alvares, who created in me an abiding love of science and the importance of systematic work. The interest in science was strengthened during my late teens by my close friendship with Radhakrishnan and Ramaseshan from the family of Professor Raman, the Nobel Laureate in Physics. I went on to do my B.Sc. (Honors) in Chemistry and M.Sc. in Physical Chemistry in Central College, Bangalore, after which I went to U.K. -

Preamble / Objective the Bachelor of Architecture Degree Programme Prepares Students for Professional Practice in the Field of A

Preamble / Objective The Bachelor of Architecture degree programme prepares students for professional practice in the field of Architecture. Being an undergraduate programme, it has bright scope, providing exposure to a variety of interests in this field and assisting students to discover their own directions for future development. There is increasing recognition today of Architecture as an intellectual discipline, both as art& science and as a profession. Through architectural design, Architects make vital contribution in defining and shaping our environment and future of society with the use of appropriate technologies for a diverse range of situations, both in the rural and urban contexts. Considering the diverse Indian complexities in terms of social, cultural, geographical, climatic, economic and technical aspects, which are unique and typical of every region in our country, the task for profession of Architecture becomes all the more challenging. Making provision of most optimum and sustainable solutions/ options ,to address the basic needs of living, working and care of body and soul(three basic human functions) of even the poorest of the poor, to lead a productive and dignified life, demand appropriate skills, understanding, knowledge and a deep commitment to professed ideals. Addressing Architectural Design as a comprehensive creative process, this UG programme leading to B. Architecture, is based on the following broad objectives; a) To stimulate sensitivity and unveil creative talents. b) To reinforce intellectual capabilities and develop proficiency in professional skills to enable graduates to competently pursue alternative careers, within the broad spectrum of architecture. c) To provide opportunities to students to try out the role they will eventually play as responsible members of the society, under supervision and interactive guidance. -

'Indian Architecture' and the Production of a Postcolonial

‘Indian Architecture’ and the Production of a Postcolonial Discourse: A Study of Architecture + Design (1984-1992) Shaji K. Panicker B. Arch (Baroda, India), M. Arch (Newcastle, Australia) A Thesis Submitted to the University of Adelaide in fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Architecture, Landscape Architecture and Urban Design Centre for Asian and Middle Eastern Architecture 2008 Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................................................................................iv Declaration ............................................................................................................................................................................................vi Acknowledgements..........................................................................................................................................................................vii List of Figures ........................................................................................................................................................................................ ix 1 Introduction ........................................................................................... 1 1.1: Overview..................................................................................................................................................................1 1.2: Background...........................................................................................................................................................2 -

List of Books in Collection

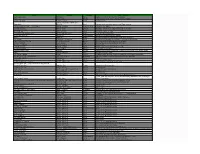

Book Author Category Biju's remarks Mera Naam Joker Abbas K.A Novel made into a film by and starring Raj Kapoor Zed Abbas, Zaheer Cricket autobiography of the former Pakistan cricket captain Things Fall Apart Achebe, Chinua Novel Nigerian writer Aciman, Alexander and Rensin, Twitterature Emmett Novel Famous works of fiction condensed to Twitter format The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy Adams, Douglas Science Fiction a trilogy in four parts The Dilbert Future Adams, Scott Humour workplace humor by the former Pacific Bell executive The Dilbert Principle Adams, Scott Humour workplace humor by the former Pacific Bell executive The White Tiger Adiga, Aravind Novel won Booker Prize in 2008 Teachings of Sri Ramakrishna Advaita Ashram (pub) Essay great saint and philosopher My Country, My Life Advani L.K. Autobiography former Deputy Prime Minister of India Byline Akbar M.J Essay famous journalist turned politician's collection of articles The Woods Alanahally, Shrikrishna Novel translation of Kannada novel Kaadu. Filmed by Girish Karnad Plain Tales From The Raj Allen, Charles (ed) Stories tales from the days of the British rule in India Without Feathers Allen, Woody Play assorted pieces by the Manhattan filmmaker The House of Spirits Allende, Isabelle Novel Chilean writer Celestial Bodies Alharthi, Jokha Novel Omani novel translated by Marilyn Booth An Autobiography Amritraj, Vijay Sports great Indian tennis player Brahmans and Cricket Anand S. Cricket Brahmin community's connection to cricket in the context of the movie Lagan Gauri Anand, -

Year Book of the Indian National Science Academy

AL SCIEN ON C TI E Y A A N C A N D A E I M D Y N E I A R Year Book B of O The Indian National O Science Academy K 2019 2019 Volume I Angkor, Mob: 9910161199 Angkor, Fellows 2019 i The Year Book 2019 Volume–I S NAL CIEN IO CE T A A C N A N D A E I M D Y N I INDIAN NATIONAL SCIENCE ACADEMY New Delhi ii The Year Book 2019 © INDIAN NATIONAL SCIENCE ACADEMY ISSN 0073-6619 E-mail : esoffi [email protected], [email protected] Fax : +91-11-23231095, 23235648 EPABX : +91-11-23221931-23221950 (20 lines) Website : www.insaindia.res.in; www.insa.nic.in (for INSA Journals online) INSA Fellows App: Downloadable from Google Play store Vice-President (Publications/Informatics) Professor Gadadhar Misra, FNA Production Dr VK Arora Shruti Sethi Published by Professor Gadadhar Misra, Vice-President (Publications/Informatics) on behalf of Indian National Science Academy, Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg, New Delhi 110002 and printed at Angkor Publishers (P) Ltd., B-66, Sector 6, NOIDA-201301; Tel: 0120-4112238 (O); 9910161199, 9871456571 (M) Fellows 2019 iii CONTENTS Volume–I Page INTRODUCTION ....... v OBJECTIVES ....... vi CALENDAR ....... vii COUNCIL ....... ix PAST PRESIDENTS OF THE ACADEMY ....... xi RECENT PAST VICE-PRESIDENTS OF THE ACADEMY ....... xii SECRETARIAT ....... xiv THE FELLOWSHIP Fellows – 2019 ....... 1 Foreign Fellows – 2019 ....... 154 Pravasi Fellows – 2019 ....... 172 Fellows Elected (effective 1.1.2019) ....... 173 Foreign Fellows Elected (effective 1.1.2019) ....... 177 Fellowship – Sectional Committeewise ....... 178 Local Chapters and Conveners ...... -

Nature-Inspired Architecture of Laurie Baker and Toyo Ito: a Comparison

Eco-Architecture VIII 3 NATURE-INSPIRED ARCHITECTURE OF LAURIE BAKER AND TOYO ITO: A COMPARISON ANJALI SADANAND1 & RAMASAMY VEERANASAMY NAGARAJAN2 1Measi Academy of Architecture, India 2Hindustan Institute of Technology & Science, India ABSTRACT Architects dialogue with “nature” in different ways. To some, nature is considered part of architectural space and to some separate but crafted to give the illusion of a continuum. For both, nature inspires and the actual interface with nature determines their architecture. An enquiry based on the manner of this interface is the basis of this paper. The objective is to investigate what prompts an architect to construct this interface and how it impacts architecture. The expression of this interface in terms of elements of architecture and resulting form, space, structure and material will be explored in this paper, through a discussion based on a comparison between the works of two architects, Laurie Baker and Toyo Ito. Simon Unwin’s elements of architecture will be used to construct a theoretical framework for architectural elements and Heidegger’s theory on “place” will provide a phenomenological base of enquiry. This will be illustrated in terms of architectural precepts and expression in the architecture of Laurie Baker and Toyo Ito with respect to the formalizing of form and structure. Buildings of both architects will be analysed with respect to their connection with nature. Comparative discussion of five projects of each architect in their respective treatment of architectural elements such as material, roof, and wall and structure and skin will demonstrate the language of each architect in its mode of translating nature into architecture. -

Exchanging Notes Tabrez Noorani Wining and Dining at Vinoteca

The www.catalumni.com 2013 The Cathedral & John Connon Alumni Magazine IN CONVERSATION EVENTS SPOTLIGHT Exchanging Notes Wining and Dining at Vinoteca Tabrez Noorani Contents President’s Message 2 School Update 4 Spotlight Tabrez Noorani 7 Srikant Datar 8 In Conversation 19 Ranjit Barot and Ashutosh Phatak 10 Nostalgia Randy Boudrieau 13 Malvika Singh 14 Special Feature The IB at Cathedral 16 Out of the Box Gulshirin Dubash 19 20 8 Teacher Updates 20 Events 17th Annual Golf Tournament, Old Boys vs. School Team Annual Cricket Match 22 Flamingo-viewing Event 23 Vinoteca by Sula 25 Manori Summer School 26 Lighter Side (Memories) 29 Class Notes 30 Crossword 52 Editorial Team Udita Jhunjhunwala (ICSE ’84) 23 Miel Sahgal (ISC ’89) Shyla Boga Patel (ISC ’69) Mukeeta Jhaveri (ISC ’83) Mitali Anand Kalra (ISC ’89) Business Rohita Chaganlal Doshi (ISC ’75) Editorial Support, Design and Printing Priyanka Agarwal, Minaal Pednekar, Nikunj Parikh Main Cover Photo: Dhiman Chatterjee, 25 Spenta Multimedia This magazine is not for sale and is intended for internal circulation only. Any material from this magazine may not be reproduced in part or whole without written consent. Views and opinions expressed in this magazine are those of the individual authors and not necessarily those of the Publishers. The final decision on all editorial content remains with the magazine editorial committee. Published by The Cathedral and John Connon Alumni Association, 6, P.T. Marg, Mumbai 400 001 and printed at Spenta Multimedia, Peninsula Spenta, Mathuradas Mill Compound, Lower Parel, Mumbai 400 013. www.spentamultimedia.com Special thanks to the following donors for their generous contribution: Nakul Ravindrakumar Arya, Dev and Pareena 26 30 Lamba, Dhruv Chopra, Aashish Barwale, Pramila Shivdasani PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE To my fellow alumni, aving just sent our freshly minted last ball, despite a valiant 46 by Navroz Marshall. -

Annual Report 2018 – 19

1 CENTRE FOR DEVELOPMENT STUDIES Annual Report 2018-19 Centre for Development Studies (Under the aegis of Govt. of Kerala and Indian Council of Social Science Research) Prasanth Nagar, Ulloor, Thiruvananthapuram- 695011 Kerala, India Tel: 91-471- 2774200, 2448881, 2442481, Fax: 91-471-2447137 Website: www.cds.edu 2 GOVERNING BODY (As on 31 March, 2019) Shri K.M. Chandrasekhar (Chairman) (Formerly) Cabinet Secretary, Government of India Professor Sunil Mani Director, CDS. Convenor Prof. V. P. Mahadevan Pillai Members Vice-Chancellor University of Kerala, Thiruvananthapuram Prof. M Jagadesh Kumar ” Vice-Chancellor Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Prof. Anurag Kumar ” Director Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore. Dr. C Rammanohar Reddy ” Former Editor, Economic & Political Weekly, Mumbai. Prof. J. V. Meenakshi ” Department of Economics Delhi School of Economics, University of Delhi, New Delhi. Dr. A. Jayathilak, IAS ” Principal Secretary Department of Planning & Economic Affairs, Govt. of Kerala ” Member Secretary, Kerala State Planning Board, Thiruvananthapuram Prof. Virendra Kumar Malhotra ” Member Secretary Indian Council of Social Science Research, New Delhi Prof. Ajay Dubey ” School of International Studies Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. 3 Prof. Gabriel Simon Thattil ” Professor & Director Internal Quality Assurance Cell (IQAC) Department of Commerce, University of Kerala, Trivandrum Prof.U.S.Mishra ” Centre for Development Studies Trivandrum Prof. Praveena Kodoth ” Centre for Development Studies Trivandrum Prof. K.P Kannan ” Honorary Fellow, CDS Trivandrum Prof.P. Sivanandan ” Honorary Fellow, CDS Trivandrum 695 011 4 CONTENTS 1. OVERVIEW 07 I1. RESEARCH 15 (a) Culture and Development 15 (b) Decentralisation and Governance 16 (c) Gender and Development 21 (d) Human Development, Health and Education 27 (e) Industry and Trade 35 (f) Innovation and Technology 53 (g) Labour Employment and Social Security 69 (h) Macroeconmic Performance 75 (i) Migration 91 (j) Plantation Crops 114 (k) Politics and Development 117 (l) Other Studies 123 III. -

Key Note Address on Peoples Architecture and the Contributions Of

National Workshop on " Sustainable Housing Technologies” (As Part of Laurie Baker Centenary Celebrations) National Institute of Rural Development and Panchayati Raj Hyderabad 23 /24 September, 2016 Key Note Adress : Relevance of Laurie Baker in the context of contemporary human settlements challenges and technology development in India. By Kirtee Shah Hon. Director, Ahmedabad Study Action Group (ASAG) President, Habitat Forum (INHAF) Chairman, KSA Design Planning Services Pvt. Ltd. 1 1. It is indeed my privilege and also an honour to have been invited to participate and deliver the keynote address at this National Workshop on “Sustainable Housing Technologies” as part of Laurie Baker Centenary Celebrations. I have chosen as my theme “Relevance of Laurie Baker in the context of contemporary human settlements challenges and technology development in India.” 2. It is a pleasant coincidence and my humble privilege that I was also the keynote speaker at the launch of the year long countrywide celebrations for the LB centenary year in Trivandrum in March this year. A number of individuals sitting here in this meeting were present there too and I am sure they would remember my emphasizing the need to celebrate LB’s work and persona—yes, not work alone , persona too--not only in India but internationally, as LB’s philosophy, wisdom, work ethics, principles, approach, contribution and architecture are relevant to the entire world seeking alternative ways of thinking and new ways of doing things in the context of contemporary human settlements challenges. 3. I must also remind you of another pleasant coincidence that this workshop takes place in Hyderabad, at the National Institute of Rural Development and just three weeks ahead of the United Nations’ Global Conference on Human Settlements taking place in Quito, Equador. -

In the Loving Memory of Our Founder Chairman Shri.S

In the loving memory of our Founder Chairman Shri.S. Narasa Raju Garu VISION To be a respected and most sought after Engineering Educational Institution engaged in equipping individuals capable of building learning organizations in the new millennium. MISSION To develop competent students with good value system to face challenges of the continually changing world. QUALITY POLICY To equip the students with highest standard of education, knowledge and ethics. To prepare them to meet the challenges of life with full confidence. Aim at all-round development of the personality to be useful citizens. DQìgÉhÄÊ£ï 2018 Vol XIV THE OXFORD COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING (Recognised by the Govt. of Karnataka, Affiliated to VTU & Approved by AICTE) Accredited by National Assessment and Accreditation Council (NAAC) Accredited by National Board of Accreditation (NBA) Accredited to International Accreditation Organization (IAO) Bommanahalli, Hosur Road, Bangalore – 560 068 Tel : 080 - 3021 9601/ 02 Fax : 080 - 2573 0551 www.theoxford.edu Message from the Chairman The current issue of Oxyzine 2018 is a pool of potentials of the venture contemplated by the faculty and students who have dedicatedly been involved for exposition of their creative and artistic trait besides perceptions and projection of their literary talents for fulfillment of their missions. All the articles are immensely beneficial in pursuit of achieving excellence and for enlightenment of readers leading to multiple frontiers. It also reflects the multifarious beyond curricular activities crept in the College to emerge as a significant player in the technological education landscape focusing the character building. SNVL NARASIMHA RAJU Chairman, Children’s Education Society® & The Oxford Educational Institutions Message from the Director Glad to note that The Oxford College of Engineering (TOCE) is coming up with its 14th Volume of annual college magazine ‘Oxyzine’. -

Master Mason Page 1 of 7

Master mason Page 1 of 7 Volume 24 - Issue 07 :: Apr. 07-20, • Contents 2007 INDIA'S NATIONAL MAGAZINE from the publishers of THE HINDU TRIBUTE Master mason G. SHANKAR Perhaps more than for his architecture, people loved him for his wonderful qualities as a human being. By G. Shankar S. GOPAKUMAR Baker's sense of humour welcomes visitors to 'The Hamlet', his home, which has the doghouse above the door. I WAS a student just out of school in Kerala when I first met Laurie Baker. A friend had invited me over to visit the site where, he said, a foreigner was building a house for his family. There I saw this fair- skinned man engaged in a heated argument with his client, my friend's father, a mathematics professor. Among other things, the professor wanted a cylindrical shape for his home, to get the benefit of maximum space, and six bedrooms, one each for his five sons and the other for himself and his wife. The argument was about the bedrooms. I still remember Baker asking the professor, "Look, Mr. Namboodiri, you have five sons, all of them brilliant students. They will all start flying very soon and will go away. Finally, an old man and an old woman will be all alone in this house. Are you sure that you still want six bedrooms?" http://www.hinduonnet.com/fline/fl2407/stories/20070420004012600.htm 5/5/2007 Master mason Page 2 of 7 The professor was adamant. He said, "Yes, I do want six bedrooms. As long as my sons are with me, they should have their own rooms." S.MAHINSHA Baker with his wife, Elizabeth, at their home in Thiruvananthapuram. -

Kerala Post Disaster Needs Assessment Floods and Landslides - August 2018

European Union Civil Protecon and Humanitarian Aid Kerala Post Disaster Needs Assessment Floods and Landslides - August 2018 October 2018 European Union Civil Protecon and Humanitarian Aid Kerala Post Disaster Needs Assessment Floods and Landslides August 2018 October 2018 Acknowledgements The PDNA for the floods and landslides was made possible due to the collaborative efforts of the Government of Kerala, the Kerala State Disaster Management Authority, the United Nations agencies, the European Commission (and , Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) , European Union Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid (ECHO) The State Government would like to extend special acknowledgment to the following authorities: Departments of Agriculture, Agriculture PPM Cell, Animal Husbandry, Archaeology, Ayurveda, Childline, Civil Supplies, Coir Board, Cooperative Department, Dairy Development, Department of Culture of T.K Karuna Das, District Child Protection Unit (Pathanamthitta), Economics and Statistics, Environment & Climate Change, Fire and Rescue, Fisheries, Health Services, Higher Education, Homoeopathy, Industries & Commerce, Insurance Medical Services, Kerala Forest Department, Kerala Water Authority, Labour, Local Self-Government, National Health Mission, Police Head Quarters, Public Instruction (General Education), Rashtriya Madhyamik Shiksha Abhiyan (RMSA), Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Department, State Council Educational Research and Training (SCERT), Social Forestry, Social Justice, Suchitwa Mission, Kerala State Civil