ANTISTAPHYLOCOCCAL and ANTIBIOFILM ACTIVITIES of ETHANOLIC EXTRACT of Piper Cubeba L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chemical Composition, Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Activities of the Essential Oil of Piper Cubeba L

Romanian Biotechnological Letters Vol. 22, No. 2, 2017 Copyright © 2017 University of Bucharest Printed in Romania. All rights reserved ORIGINAL PAPER Chemical composition, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities of the essential oil of Piper cubeba L. Received for publication, October 8, 2015 Accepted, April 22, 2016 RAMZI A. MOTHANA1,*, MANSOUR S. AL-SAID1, MOHAMMAD RAISH2, JAMAL M. KHALED3, NAIYF S. ALHARBI3, ABDULRAHMAN ALATAR3, AJAZ AHMAD4, MOHAMMED AL-SOHAIBANI5, MOHAMMED AL-YAHYA1, SYED RAFATULLAH1. 1Department of Pharmacognosy and Medicinal, Aromatic & Poisonous Plants Research Center (MAPPRC), College of Pharmacy, King Saud University, P.O. Box 2457, Riyadh 11451, Saudi Arabia. 2Department of Pharmaceutics, College of Pharmacy, King Saud University, P.O. Box 2457, Riyadh 11451, Saudi Arabia. 3Departments of Botany and Microbiology, College of Science, King Saud University, Riyadh 11451, Saudi Arabia 4Department of Clinical Pharmacy, College of Pharmacy, King Saud University, P.O. Box 2457, Riyadh 11451, Saudi Arabia. 5Department of Medicine and Pathology, Gastroenterology Unit, College of Medicine, King Khalid University Hospital, King Saud University, P.O. Box 2925, Riyadh-11461 Saudi Arabia. *Address for correspondence to: [email protected] or [email protected]; Abstract Piper Cubeba (L.) is used as a remedy for various ailments. However, the scientific basis for its medicinal use, especially as anti-inflammation remains unknown. Therefore, the present study aims to investigate the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities of Piper cubeba essential oil (PCEO) in laboratory rodent models. The in vivo anti-inflammatory activity of PCEO at three doses (150, 300 and 600 mg /kg, p.o) was tested in carrageenan-induced rat paw edema, cotton pellet granuloma and carrageenan-induced pleurisy. -

62 of 17 January 2018 Replacing Annex I to Regulation (EC) No 396/2005 of the European Parliament and of the Council

23.1.2018 EN Official Journal of the European Union L 18/1 II (Non-legislative acts) REGULATIONS COMMISSION REGULATION (EU) 2018/62 of 17 January 2018 replacing Annex I to Regulation (EC) No 396/2005 of the European Parliament and of the Council (Text with EEA relevance) THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION, Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Having regard to Regulation (EC) No 396/2005 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 February 2005 on maximum residue levels of pesticides in or on food and feed of plant and animal origin and amending Council Directive 91/414/EEC (1), and in particular Article 4 thereof, Whereas: (1) The products of plant and animal origin to which the maximum residue levels of pesticides (‘MRLs’) set by Regulation (EC) No 396/2005 apply, subject to the provisions of that Regulation, are listed in Annex I to that Regulation. (2) Additional information should be provided by Annex I to Regulation (EC) No 396/2005 as regards the products concerned, in particular as regards the synonyms used to indicate the products, the scientific names of the species to which the products belong and the part of the product to which the respective MRLs apply. (3) The text of footnote (1) in both Part A and Part B of Annex I to Regulation (EC) No 396/2005 should be reworded, in order to avoid ambiguity and different interpretations encountered with the current wording. (4) New footnotes (3) and (4) should be inserted in Part A of Annex I to Regulation (EC) No 396/2005, in order to provide additional information as regards the part of the product to which the MRLs of the products concerned apply (5) New footnote (7) should be inserted in Part A of Annex I to Regulation (EC) No 396/2005, in order to clarify that MRLs of honey are not applicable to other apiculture products due to their different chemicals character istics. -

Phytochemical Evaluation and Antioxidant Activity of Piper Cubeba

Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science 01 (08); 2011: 153-157 ISSN: 2231-3354 Phytochemical Evaluation and Antioxidant Received on: 08-10-2011 Revised on: 12:10:2011 Accepted on: 15-10-2011 activity of Piper cubeba and Piper nigrum Gayatri Nahak and R.K. Sahu ABSTRACT Indian spices that provide flavor, color, and aroma to food also possess many therapeutic properties. Ancient Indian texts of Ayurveda, an Indian system of medicine, detailed the medicinal properties of these plants and their therapeutic usage. Recent scientific research has established the presence of many active compounds in these spices that are known to possess specific pharmacological properties. The therapeutic efficacy of these individual spices Gayatri Nahak and R.K. Sahu for specific pharmacological actions has also been established by experimental and clinical B.J.B. Autonomous College, studies. The medicinal effects traditionally ascribed to Indian spices are validated by modern Botany Department, pharmacological and experimental techniques, thus providing a scientific rationale to their Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India traditional therapeutic usage. Many plant-derived molecules have shown a promising effect in therapeutics. Among the plants investigated to date, one showing enormous potential is the Piperaceae. Piperine is an alkaloid found naturally in plants belonging to the pyridine group of Piperaceae family, such as Piper nigrum and Piper cubeba. It is widely used in various herbal cough syrups and it is also used in anti inflammatory, anti malarial, anti leukemia treatment. So the present study was aimed to extract the phytochemical compounds in different solvent system in Piper nigrum and Piper cubeba. In preliminary screening and confirmatory test it was identified as alkaloid. -

118 SECTION-II CHAPTER-9 Coffee, Tea, Mate and Spices 1. Mixtures Of

SECTION-II 118 CHAPTER-9 CHAPTER 9 Coffee, tea, mate and spices NOTES : 1. Mixtures of the products of headings 0904 to 0910 are to be classified as follows: (a) mixtures of two or more of the products of the same heading are to be classified in that heading; (b) mixtures of two or more of the products of different headings are to be classified in heading 0910. The addition of other substances to the products of headings 0904 to 0910 [or to the mixtures referred to in paragraph (a) or (b) above] shall not affect their classification provided the resulting mixtures retain the essential character of the goods of those heading. Otherwise such mixtures are not classified in this Chapter; those constituting mixed condiments or mixed seasonings are classified in heading 2103. 2. This Chapter does not cover Cubeb pepper (Piper cubeba) or other products of heading 1211. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES : (1) Heading 0901 includes coffee in powder form. (2) “Spice” means a group of vegetable products (including seeds, etc.), rich in essential oils and aromatic principles, and which, because of their characteristic taste, are mainly used as condiments. These products may be whole or in crushed or powdered form. (3) The addition of other substances to spices shall not affect their inclusion in spices provided the resulting mixtures retain the essential character of spices and spices also include products commonly known as “masalas”. Tariff Item Description of goods Unit Rate of duty Standard Prefer- ential Areas (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) 0901 COFFEE, WHETHER OR NOT ROASTED OR DACAFFEINATED; COFFEE HUSKS AND SKINS; COFFEE SUBSTITUTES CONTAINING COFFEE IN ANY PROPORTION ííí- Coffee, not roasted : 0901 11 íí-- Not decaffeinated : í--- Arabica plantation : 0901 11 11 ---- A Grade kg. -

Review of Plants Used As Kshar of Family Piperaceae

ISSN: 0976-5921 International Journal of Ayurvedic Medicine, 2010, 1(2), 81-88 REVIEW OF PLANTS USED AS KSHAR OF FAMILY PIPERACEAE Gupta V*, Meena AK 1, Krishna CM 3, Rao MM 1, Sannd R 1, Singh H 1, Panda P 1, Padhi MM2 and Ramesh Babu2 1National Institute of Ayurvedic Pharmaceutical Research, Patiala-147001, Punjab 2Central Council for Research in Ayurveda and Siddha, Janakpuri, Delhi-110058 3National Institute of Indian Medical Heritage, Hyderabad, India Abstract Many herbal remedies individually or in combination have been recommended in various medical treatises for the cure of different diseases. Kshara is a kind of medication described in Ayurveda Texts for the management of various disorders. The genus Piper L. is estimated to contain over 1000 species which are distributed mainly in tropical regions of the world. This review mainly focuses on the plants of family Piperaceae that are used in Kshar so that more research work is carried out in the direction of standardization, therapeutic level determination of Kshar plants. Keywords: Kshar, Piper, Piperaceae, Herbal remedies INTRODUCTION Drug Used The word Kshara is derived from Many drugs have been advised by the root Kshar, means to melt away or to Sushruta and other Ayurvedic texts for the perish. Acharya Sushruta defines as the preparation of Kshara (Ghanekar 1998, material which destroys or cleans the Sharma et al. 1995) excessive/the morbid doshas (Kshyaranat Method of Preparation Kshyananat va Kshara). According to the According to the three types of preparation we can consider it to be caustic Ksharas are prepared on the basis of their materials, obtained from the ashes after strength. -

Antimicrobial and Wound Healing Potential of a New Chemotype from Piper Cubeba L

plants Article Antimicrobial and Wound Healing Potential of a New Chemotype from Piper cubeba L. Essential Oil and In Silico Study on S. aureus tyrosyl-tRNA Synthetase Protein Fahad Alminderej 1, Sana Bakari 2, Tariq I. Almundarij 3, Mejdi Snoussi 4,5 , Kaïss Aouadi 1,6 and Adel Kadri 2,7,* 1 Department of Chemistry, College of Science, Qassim University, Buraidah 51452, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] (F.A.); [email protected] (K.A.) 2 Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science of Sfax, University of Sfax, B.P. 1171, Sfax 3000, Tunisia; [email protected] 3 Department of Veterinary Medicine, College of Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine, Qassim University, PO Box 6622, Buraidah 51452, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] 4 Department of Biology, College of Science, Hail University, P.O. Box 2440, Ha’il 2440, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] 5 Laboratory of Genetics, Biodiversity and Valorization of Bio-Resources (LR11ES41), University of Monastir, Higher Institute of Biotechnology of Monastir, Avenue Tahar Haddad, BP74, Monastir 5000, Tunisia 6 Faculty of Sciences of Monastir, University of Monastir, Avenue of the Environment, Monastir 5019, Tunisia 7 Faculty of Science and Arts in Baljurashi, Albaha University, P.O. Box (1988), Albaha 65527, Saudi Arabia * Correspondence: [email protected]; Fax: +216-74-27-44-37 Abstract: Piper cubeba is an important plant commonly known as cubeb or Java pepper, and it is cultivated for its fruit and essential oils, largely used to treat various diseases. Up to today, there was no scientific report on wound healing activity. Thus, this study was initiated to evaluate for the first time the antimicrobial activity and wound healing potential of a new chemotype from Piper cubeba Citation: Alminderej, F.; Bakari, S.; essential oil (PCEO) from fruits. -

Herbs, Spices and Essential Oils

Printed in Austria V.05-91153—March 2006—300 Herbs, spices and essential oils Post-harvest operations in developing countries UNITED NATIONS INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION Vienna International Centre, P.O. Box 300, 1400 Vienna, Austria Telephone: (+43-1) 26026-0, Fax: (+43-1) 26926-69 UNITED NATIONS FOOD AND AGRICULTURE E-mail: [email protected], Internet: http://www.unido.org INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION OF THE ORGANIZATION UNITED NATIONS © UNIDO and FAO 2005 — First published 2005 All rights reserved. Reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product for educational or other non-commercial purposes are authorized without any prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of material in this information product for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holders. Applications for such permission should be addressed to: - the Director, Agro-Industries and Sectoral Support Branch, UNIDO, Vienna International Centre, P.O. Box 300, 1400 Vienna, Austria or by e-mail to [email protected] - the Chief, Publishing Management Service, Information Division, FAO, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00100 Rome, Italy or by e-mail to [email protected] The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations Industrial Development Organization or of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

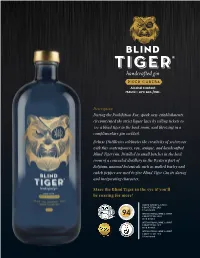

Blind Tiger Piper Cubeba Without Price

Alcohol Content 750 ml – 47% ALC./VOL. Description During the Prohibition Era, speak easy establishments circumvented the strict liquor laws by selling tickets to 'see a blind tiger in the back room', and throwing in a complimentary gin cocktail. Deluxe Distilleries celebrates the creativity of yesteryear with this contemporary, raw, unique, and handcrafted Blind Tiger Gin. Distilled in small batches in the back room of a concealed distillery in the Western part of Belgium, unusual botanicals such as malted barley and cubeb pepper are used to give Blind Tiger Gin its daring and invigorating character. Stare the Blind Tiger in the eye & you’ll be roaring for more! TOKYO WHISKY & SPIRITS COMPETITION 2021 Silver Award INTERNATIONAL WINE & SPIRIT COMPETITION 2020 Gold Award INTERNATIONAL WINE & SPIRIT COMPETITION 2019 Gold Award INTERNATIONAL WINE & SPIRIT COMPETITION 2018 Silver Award 15 BOTANICALS Juniper berries, coriander seeds, malted barley, licorice root, angelica root, orris root, lemon peel, sweet orange peel, bitter orange peel, orange blossom, ginger rhizome, green cardamom, cubeb berries, lavender & a secret belgian botanical. THE PROCESS Our botanicals (except the cubeb berries) are macerated & distilled in a copper pot still (400l). We add the double distilled cubeb pepper afterwards. Tasting Notes The higher than average alcohol content carries bags of juniper and cubeb pepper which lingers on with zesty hints of cracked black pepper, violet, orange and liquorice. The waft of celeriac from the blinded botanical in the nose gives way to herbal and floral notes of orange blossom and some citrus on the first sip. The palate is complex with a peppery kick and the malted barley introduces a long and warming aftertaste with some more cracked pepper and cubeb and earthy notes of ginger, liquorice & cardamom. -

New Sauce Products from Some Natural Plant Sources

1 Middle East Journal of Applied Sciences 4(1): 1-5, 2014 ISSN 2077-4613 New Sauce Products from Some Natural Plant Sources El-Sayed M. El-Saeidy; Ginat El-Sherif and Azza Abdel Hameed. K. Food Technology Research Institute . Agric. Rec. Center, Giza, Egypt ABSTRACT This study was carried out to produce new products with good ability in form (sauce) from some natural plant sources such bas red rosella (Hibiscus sabdariffal) and tamarind ( Tamarindus indicia L.) and evaluate these products. The obtained results showed that tamarind sauce (T4) was found to be the most acidic sauce compared to the others, all the samples present relatively low content of fibers and high levels of acidity, total phenols and flavonoids compounds .(T6) contain high amount of total phenols (718.75mg/100 g as Gallic acid), while total flavonoids compounds ranged from 54.4 (T3) to 171.0(T2) mg/100 g as Quercetin . pyrogallol recorded the highest amount in al treatment except (T2) and (T5), while (T2) recorded high amount of chlorogenic (95.463 mg/100g). mean while all treatments contain rosemarinic and Quercetin as flavonoids, hisperidin recorded the highest levels in all treatments. Key words: -sauce, red rosella, tamarind, phenol compounds, chlorogenic, rosemarinic. Introduction The Hibiscus sabdariffa L. (family: Malvaceae), usually named bissap, karkade or rosella is a tropical plant commonly used as local soft drink. It is highly appreciated all over the world for the particular sensation of freshness conveyed (Wang, et al. 2000 and Salvador Ferndndez-Arroyo, et al. 2011). The brilliant red color and unique flavor make it a valuable food product. -

Antimicrobial Efficacy of Leaf Extracts of Piper Nigrum Against Escherichia Coli, Staphylococcus Aureus and Candida Albicans

Kigigha LT et al. Antimicrobial activity of P. nigrum leaves 32 JOURNAL OF BASIC Original Research Article PHARMACOLOGY AND TOXICOLOGY Antimicrobial efficacy of leaf extracts of Piper nigrum against Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus and Candida albicans Lovet T. Kigigha, Chidinma Grace Kalunta* Department of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science, Niger Delta University, Wilberforce Island, Bayelsa state, Nigeria. Abstract This study investigated the antimicrobial activity of Piper nigrum leaves extracts (hot water, cold water and pepper soup) on Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus and Candida albicans. The fresh leaves of climbing pepper were bought at Swali Market, Yenagoa, Bayelsa State of Nigeria. Hot and cold-water extracts and pepper soup made with the leaves were used for the sensitivity test. Filter paper disc method was used for the determination of zone of inhibition. Ampiclox (1%) was used as the positive control (AMP). The mean zone of inhibition for S. aureus, E. coli and C. albicans were 12.52 mm, 12.61 mm and 11.23 mm respectively (cold water leave viz: CWL), 13.16 mm, 13.57 mm and 11.49 mm respectively (hot water leave viz: HWL), 13.46 mm, 13.60 mm and 13.31 mm respectively (pepper soup extract leave viz: PEPL) and 12.07 mm, 12.31 mm and 12.03 mm respectively (1% concentration of the ampiclox used as positive control viz: AMP). Analysis of variance showed that there was a significant variation (p < 0.05) among the various isolates for each of the different extracts apart from PEPL. The phytochemical screening revealed the presence of tannins, flavonoids, cardiac glycosides and alkaloids in the leaves of P. -

Show Activity

A Thermogenic *Unless otherwise noted all references are to Duke, James A. 1992. Handbook of phytochemical constituents of GRAS herbs and other economic plants. Boca Raton, FL. CRC Press. Plant # Chemicals Total PPM Abies alba Silver-Fir 1 Acacia farnesiana Cassie; Huisache; Popinac; Sweet Acacia; Opopanax 1 Achillea millefolium Milfoil; Yarrow 1 Actaea racemosa Black Cohosh; Black Snakeroot 1 Actaea cimicifuga Sheng ma; Bugbane; Foetid Bugbane 1 Aframomum melegueta Guinea Grains; Grains-of-Paradise; Melegueta Pepper; Malagueta (Sp.); Malagettapfeffer (Ger.); Alligator 2 Pepper Agrimonia eupatoria Agrimony; Sticklewort 1 Allium sativum var. sativum Garlic 1 Althaea officinalis Marshmallow; White Mallow 1 Anacardium occidentale Cashew 1 Anethum graveolens Dill; Garden Dill 1 Arachis hypogaea Peanut; Groundnut 1 36.0 Arctostaphylos uva-ursi Bearberry; Uva Ursi 1 Artemisia dracunculus Tarragon 1 6.0 Artemisia absinthium Wormwood 1 Beta vulgaris Beet; Garden Beet; Sugar Beet; Beetroot 1 Betula lenta Cherry Birch 1 Bixa orellana Bija; Achiote; Annatto; Lipstick Pod; Annoto; Lipsticktree; Arnato; Annato 1 Brassica oleracea var. italica Calabrese; Winter Broccoli; Heading Broccoli; Purple Cauliflower; Broccoli; Sprouting Broccoli; Cape 1 Broccoli; Asparagus Broccoli Brassica oleracea var. botrytis l. Cauliflower 1 Calea zacatechichi Mexican Calea; Dog's Grass; Bitter Grass 1 Calendula officinalis Calendula; Pot-Marigold 1 0.68 Camellia sinensis Tea 2 Cananga odorata Cananga; Ylang-Ylang 1 Capsicum frutescens Spur Pepper; Cayenne; Chili; Tabasco; -

SHB-Botanical-Index.Pdf

List of botanical and common names for herbs and spices copyright Ian Hemphill 2016 INDEX OF BOTANICAL NAMES OF SPICES & HERBS in The Spice & Herb Bible Third Edition by Ian Hemphill, Published by Robert Rose Inc. Canada BOTANICAL NAME FAMILY COMMONLY USED NAMES PAGE www.herbies.com.au Carum ajowan Apiaceae ajwain, bishop's weed, carum 46 Trachyspermum ammi Apiaceae ajwain, bishop's weed, carum 46 Solanum centrale Solanaceae akudjura, kutjera, bush tomato, desert raisins 52 Solanum chippendalei Solanaceae akudjura, kutjera, bush tomato, desert raisins 52 Smyrnium olusatrum Apiaceae black lovage, horse parsley, potherb, smyrnium, wild celery 57 Pimenta dioica Myrtaceae bay rum berry, clove pepper, pimento, Jamaica pepper 61 Pimenta racemosa Myrtaceae bayberry tree 61 Calycanthus floridus Myrtaceae Carolina allspice 61 Calycanthus occidentalis Myrtaceae Californian allspice 61 Mangifera indica Anacardiaceae amchur, amchoor, green mango powder 68 Angelica archangelica Apiaceae garden angelica, great angelica, holy ghost, masterwort 73 Archangelica officinalis Apiaceae garden angelica, great angelica, holy ghost, masterwort 73 Pimpenella anisum Apiaceae aniseed, anise, anise seed, sweet cumin 78 Bixa orellana Bixaceae annatto, achiote, bija, latkhan, lipstick tree, roucou 83 Ferula asafoetida Apiaceae asafoetida, asafetida, devil's dung, hing, hingra, laser 89 Melissa officinalis Lamiaceae balm, bee balm, lemon balm, melissa, sweet balm 94 Berberis vulgaris Berberidaceae barberry, holy thorn, jaundice berry, zareshk, sowberry 100 Ocimum basilicum Lumiaceae basil, sweet basil 104 Ocimum basilicum minimum Lumiaceae bush basil 104 Ocimum cannum sims Lumiaceae Thai basil 104 Page 1 of 12 List of botanical and common names for herbs and spices copyright Ian Hemphill 2016 INDEX OF BOTANICAL NAMES OF SPICES & HERBS in The Spice & Herb Bible Third Edition by Ian Hemphill, Published by Robert Rose Inc.