University of Groningen Struggling for Recognition and Affordable Housing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Geological History of Groningen's Subsurface

A geological history of Groningen’s subsurface Erik Meijles, University of Groningen Date June 2015 Editors Jan van Elk & Dirk Doornhof Translated by E.L. Howard General introduction Ground acceleration caused by an induced earthquake is strongly dependent on the composition of local shallow soils. NAM commissioned Deltares to conduct a detailed survey of the shallow subsurface above the Groningen gas field. The survey focuses on Quaternary geology with an emphasis on the upper 50 metres. This report provides an introduction to Groningen’s Quaternary geology as a background to the comprehensive Deltares report, which has culminated in a detailed model of Groningen’s shallow subsurface. This report was written by Dr ir Erik Meijles, Assistant Professor of Physical Geography at the University of Groningen. Wim Dubelaar, Dr Jan Stafleu and Dr Wim Westerhoff of TNO Geological Survey of the Netherlands (TNO- NITG) in Utrecht assisted with editing this report and provided a number of key diagrams. Title A geological history of Groningen’s subsurface Date June 2015 Client NAM Author Erik Meijles, Assistant Professor Edited by Jan van Elk of Physical Geography and Dirk Doornhof Organization University of Groningen Organization NAM Significance for Research theme: earthquake Predicting ground acceleration research Explanation: Ground acceleration caused by an induced earthquake is strongly dependent on the composition of local shallow soils. NAM commissioned Deltares to conduct a detailed survey of the shallow subsurface above the Groningen gas field. This survey focuses on the Quaternary geology of Groningen with an emphasis on the upper 50 metres. Directly This research serves as background to the report entitled ‘Geological schematisation of related the shallow subsurface of Groningen’ written by various Deltares staff members. -

Main Results Test with Hydrogen Train in Groningen

MAIN RESULTS TEST WITH HYDROGEN TRAIN IN GRONINGEN CONTENTS Main Results of the Hydrogen Train Test in Groningen Result of test with hydrogen train in Groningen .......................................................4 The Test Dispensation .................................6 The Trial Runs ................................................7 The Refueling Process ..............................17 Press- and Public Information Day ........21 RESULT OF TEST WITH HYDROGEN TRAIN IN GRONINGEN At the start of 2020, after a long preparation period of as much as one and a half year, the Province of Groningen, together with various partners, did a feasibility study in the form of a pilot test with a hydrogen (battery) train (running on green hydrogen) to explore whether this could be a full-fledged sustainable alternative to the current diesel trains. The Province of Groningen sees an important role for green hydrogen • For greening the chemical sector (raw material). • As a fuel in heavy mobility (buses, trains, trucks, ships, aircraft). • As an essential piece of the puzzle regarding energy transition (storage, transportation). • This will also create new economic opportunities and employment. Pilot The trial runs were done on the track between Groningen and Leeuwarden during nighttime for a period of two weeks, with a passenger train running on green hydrogen. During the tests, the train ran a number of times at normal speed – without passengers – alternately as an intercity- and a local train – between the stations of Groningen and Leeuwarden. By these trial runs, practical experience was gained in running on hydrogen. This was the first time a train ran on hydrogen in the Netherlands. The tests focused on, among other things, the actual running, fuel consumption, and refueling. -

University of Groningen Struggling for Recognition and Affordable Housing

University of Groningen Struggling for recognition and affordable housing in Amsterdam and Hamburg Buchholz, Tino IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2016 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Buchholz, T. (2016). Struggling for recognition and affordable housing in Amsterdam and Hamburg: Resignation, resistance, relocation. University of Groningen. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 28-09-2021 Struggling for recognition and affordable housing in Amsterdam and Hamburg: resignation, resistance, relocation Tino Buchholz dedicated to M ISBN: 978-90-367-8973-8 Copyright © 2016, Tino Buchholz. -

Zwolle, Leeuwarden/Groningen

richting/direction Zwolle, Leeuwarden/Groningen SteenwijkHeerenveenLeeuwarden AmersfoortAmersfoortAmersfoort CentraalNijkerk SchothorstPutten VathorstErmeloHarderwijkNunspeet't HardeWezepZwolleMeppel _` _` _` _` ` ` ` _` ` AssenGroningen _` _` De informatie op deze vertrekstaat kan zijn gewijzigd. Plan uw reis op ns.nl, in de app of raadpleeg de schermen met actuele vertrekinformatie op dit station. The information on this board may be subject to changes. Check your journey plan on ns.nl or consult the displays with real-time travel information at this station. Vertrektijd/ Treinen rijden op/ Spoor/ Soort trein/ Eindbestemming/ Vertrektijd/ Treinen rijden op/ Spoor/ Soort trein/ Eindbestemming/ Departure Trains run on Platf. Transportation Destination Departure Trains run on Platf. Transportation Destination 12 ma di wo 1 Sprinter Zwolle via Harderwijk 04 ma di wo do vr za zo 2 Intercity Groningen via Zwolle-Assen 6 12 do vr za 2 Sprinter Zwolle via Harderwijk 16 12 ma di wo do vr za zo 2 Sprinter Zwolle via Harderwijk 34 ma di wo do vr 2 Intercity Leeuwarden via Zwolle-Steenwijk-Heerenveen, stopt ook in/also calls 22 ma di wo do vr za zo 2 Intercity Amersfoort Schothorst at Meppel 29 ma di wo do vr za zo 1 Sprinter Amersfoort Vathorst 42 ma di wo do vr za 2 Sprinter Zwolle via Harderwijk 34 ma di wo do vr za zo 2 Intercity Leeuwarden via Zwolle-Steenwijk-Heerenveen, stopt ook in/also calls 49 ma di wo do vr 1 Intercity Amersfoort Schothorst at Meppel 59 ma di wo do vr 1 Sprinter Amersfoort Vathorst 39 ma di wo do vr 5b Sprinter Harderwijk, -

WESTERTERP CV.Pdf

CURRICULUM VITAE Professor Klaas R Westerterp Education MSc Biology, University of Groningen, The Netherlands, 1971. Thesis: The energy budget of the nestling Starling Sturnus vulgaris: a field study. Ardea 61: 127-158, 1973. PhD University of Groningen, The Netherlands, 1976. Thesis: How rats economize – energy loss in starvation. Physiol Zool 50: 331-362, 1977. Professional employment record 1966-1971 Teaching assistant, Animal physiology, University of Groningen 1968-1971 Research assistant, Institute for Ecological Research, Royal Academy of Sciences, Arnhem 1971 Lecturer, Department of Animal Physiology, University of Groningen 1976 Lecturer, Department of Animal Ecology, University of Groningen 1977 Postdoctoral research fellow, University of Stirling, Scotland 1980 Postdoc, Animal Ecology, University of Groningen and Royal Academy of Sciences, Arnhem 1982 Senior lecturer, Department of Human Biology, Maastricht University 1998 Visiting professor, KU Leuven, Belgium 2001 Professor of Human Energetics, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University Research The focus of my work is on physical activity and body weight regulation, where physical activity is measured with accelerometers for body movement registration and as physical activity energy expenditure, under confined conditions in a respiration chamber and free-living with the doubly labelled water method. Management, advisory and editorial board functions Head of the department of Human Biology (1999-2005); PhD dean faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences (2007- 2011); member of the FAO/WHO/UNU expert group on human energy requirements (2001); advisor Philips Research (2006-2011); advisor Medtronic (2006-2007); editor in chief Proceedings of the Nutrition Society (2009-2012); editor in chief European Journal of Applied Physiology (2012-present). -

Province House

The Province House SEAT OF PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENT Colophon Production and final editing: Province of Groningen Photographs: Alex Wiersma and Jur Bosboom (Province of Groningen), Rien Linthout and Jenne Hoekstra Provincie Groningen Postbus 610 • 9700 AP Groningen +31 (0)50 - 316 41 60 www.provinciegroningen.nl [email protected] 2020 The Province House Seat of Provincial Government PREFACE The present and the past connected with each other. That is how you could describe the Groningen Province House. No. 12 Martinikerkhof is the ‘old’ Province House, which houses the State Hall where the Provincial Council has met since 16 June 1602. That is unique for the Netherlands. No other province has used the same assembly hall for so long. The connection with the present is formed by the aerial bridge to the ‘new’ Province House. This section of the Province House was designed by the architect Mels Crouwel and was opened on 7 May 1996 by Queen Beatrix. Both buildings have their own ambiance, their own history and their own works of art. The painting ‘Religion and Freedom’ by Hermannus Collenius (1650-1723) hangs in the State Hall and paintings by the artistic movement De Ploeg are in the building on the Martinikerkhof. The new section features work by contemporary artists such as Rebecca Horn. Her ‘The ballet of the viewers’ hangs in the hall. The binoculars observe the entrance hall and look out, through the transparent façades, to the outside world. But there is a lot more to see. And this brochure tells you everything about the past and present of the Province House. -

The Development of Diagnostic Competence: a Comparison

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 385 190 HE 028 456 AUTHOR Schmidt, Henk G.; And Others TITLE The Development of Diagnostic Competence:A Comparison between a Problem-Based,an Integrated, and a Conventional Medical Curriculum. PUB DATE Apr 95 NOTE 14p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meetingof the American Educational Research Association (San Francisco, CA, April 18-22, 1995). PUB TYPE Reports Research/Technical (143) Speeches /Conference Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Clinical Diagnosis; ConventionalInstruction; *Educational Methods; Experience; ForeignCountries; Higher Education; *InstructionalEffectiveness; *Integrated Curriculum; *MedicalEducation; Medical Students; Problem Solving IDENTIFIERS *Netherlands; *Problem Based Learning ABSTRACT This study compared the diagnosticperformance of 612 second-, third-, fourth-, fifth-, andsixth-year students from three Dutch medical schools who were educated ineither a problem-based,an integrative, or a conventional curriculum.The students were presented with 30 carefully selected clinicalcases to diagnose. The study found that, overall, the studentstrained within the problem-based and integrated frameworksdisplayed better diagnostic performance than students trained withina conventional curriculum. No overall differences were found between the problem-based andthe integrated curriculum, althoughsecond- and third-year students from the latter excelled the comparableyear groups in the other curricula formats. The study concludes thatintegration between basic and clinical sciences -

CHRISTIAEN COEVERSHOFF (Groningen 1595– the Hague 1659)

CHRISTIAEN COEVERSHOFF (Groningen 1595– The Hague 1659) “Elegant Portrait of a Young Boy with Amulet” oil on panel 97.7 x 74.7cm Signed Work and Dated Work with Inscription “Aetatis sua jen fen ha anno 1633” For the month of November, the Soraya Cartategui Gallery is pleased to present you this very special and delicate portrait by the enigmatic Dutch painter Christiaen Coevershoff. The artist was born in Groningen in 1595 and died in The Hague at the age of sixty-four. Coevershoff specialized in portraiture and Christian religious representations and was most active in the cities of Amsterdam, Enkhuizen, and The Hague. Documentation of the time show that Christiaen Coevershoff was married to Janneke Seghers in Amsterdam in 1617. After having children in 1619 and 1621, the family disappeared from Amsterdam. A notarial act of 1639 shows that Coevershoff was then living in the city of Enkhuizen, where he produced some signed portraits. Further documentation indicates that Coevershoff was remarried in The Hague, but under the alias of Cornelis Jansz van Groningen and without indication of his previous marriage. It is likely that he took an assumed name to avoid paying the maternal portion to his daughter. Furthermore, despite his rather tenuous financial condition, Coevershof appropriated the title of Joncheer (a Dutch honorific of nobility) and changed his age. He second wife was Catharina Hellemans, daughter of the goldsmith and jeweler Cornelis Hellemans. In 1656, Couvershoff was one of the founding members of the Confrerie Pictura in The Hague. He died between January 28 and August 26 in 1659 at approximately 63 years old. -

Annex Ii List of Nodes of the Core and Comprehensive Network 1

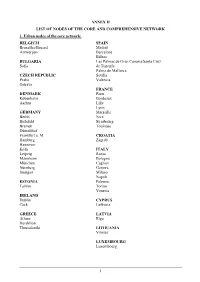

ANNEX II LIST OF NODES OF THE CORE AND COMPREHENSIVE NETWORK 1. Urban nodes of the core network: BELGIUM SPAIN Bruxelles/Brussel Madrid Antwerpen Barcelona Bilbao BULGARIA Las Palmas de Gran Canaria/Santa Cruz Sofia de Tenerife Palma de Mallorca CZECH REPUBLIC Sevilla Praha Valencia Ostrava FRANCE DENMARK Paris København Bordeaux Aarhus Lille Lyon GERMANY Marseille Berlin Nice Bielefeld Strasbourg Bremen Toulouse Düsseldorf Frankfurt a. M. CROATIA Hamburg Zagreb Hannover Köln ITALY Leipzig Roma Mannheim Bologna München Cagliari Nürnberg Genova Stuttgart Milano Napoli ESTONIA Palermo Tallinn Torino Venezia IRELAND Dublin CYPRUS Cork Lefkosia GREECE LATVIA Athina Rīga Heraklion Thessaloniki LITHUANIA Vilnius LUXEMBOURG Luxembourg 1 HUNGARY SLOVENIA Budapest Ljubljana MALTA SLOVAKIA Valletta Bratislava THE NETHERLANDS FINLAND Amsterdam Helsinki Rotterdam Turku AUSTRIA SWEDEN Wien Stockholm Göteborg POLAND Malmö Warszawa Gdańsk UNITED KINGDOM Katowice London Kraków Birmingham Łódź Bristol Poznań Edinburgh Szczecin Glasgow Wrocław Leeds Manchester PORTUGAL Portsmouth Lisboa Sheffield Porto ROMANIA București Timişoara 2 2. Airports, seaports, inland ports and rail-road terminals of the core and comprehensive network Airports marked with * are the main airports falling under the obligation of Article 47(3) MS NODE NAME AIRPORT SEAPORT INLAND PORT RRT BE Aalst Compr. Albertkanaal Core Antwerpen Core Core Core Athus Compr. Avelgem Compr. Bruxelles/Brussel Core Core (National/Nationaal)* Charleroi Compr. (Can.Charl.- Compr. Brx.), Compr. (Sambre) Clabecq Compr. Gent Core Core Grimbergen Compr. Kortrijk Core (Bossuit) Liège Core Core (Can.Albert) Core (Meuse) Mons Compr. (Centre/Borinage) Namur Core (Meuse), Compr. (Sambre) Oostende, Zeebrugge Compr. (Oostende) Core (Oostende) Core (Zeebrugge) Roeselare Compr. Tournai Compr. (Escaut) Willebroek Compr. BG Burgas Compr. -

View of These Earlier Experiences with Sulodexide, It Is Figure 2

CLINICAL RESEARCH www.jasn.org Sulodexide Fails to Demonstrate Renoprotection in Overt Type 2 Diabetic Nephropathy † ‡ ‡ | David K. Packham,* Rory Wolfe, Anne T. Reutens, § Tomas Berl, ‡ †† ‡‡ Hiddo Lambers Heerspink,¶ Richard Rohde,** Sara Ivory, Julia Lewis, Itamar Raz, || Thomas B. Wiegmann,§§ Juliana C.N. Chan, Dick de Zeeuw,¶ Edmund J. Lewis,¶¶ ‡ and Robert C. Atkins, for the Collaborative Study Group *Melbourne Renal Research Group, Melbourne, Australia; †Department of Nephrology, Royal Melbourne and Austin Hospitals, Melbourne, Australia; ‡Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia; §Baker IDI Heart and Diabetes Institute, Melbourne, Australia; |Division of Renal Diseases and Hypertension, University of Colorado, Denver, Colorado; ¶Clinical Pharmacology, University Medical Centre Groningen, Groningen, the Netherlands; **The Collaborative Study Group, Chicago, Illinois; ††Division of Nephrology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee; ‡‡Diabetes Center, Hadaza Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel; §§Renal Service, Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Kansas City, Missouri; ||Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong, SAR; and ¶¶Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois ABSTRACT Sulodexide, a mixture of naturally occurring glycosaminoglycan polysaccharide components, has been reported to reduce albuminuria in patients with diabetes, but it is unknown whether it is renoprotective. This study reports the results from the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, sulodexide macroalbuminuria (Sun-MACRO) trial, which evaluated the renoprotective effects of sulodexide in patients with type 2 diabetes, renal impairment, and significant proteinuria (.900 mg/d) already receiving maximal therapy with angiotensin II receptor blockers. The primary end point was a composite of a doubling of base- line serum creatinine, development of ESRD, or serum creatinine $6.0 mg/dl. -

Curriculum Rriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Dr Tamás Vonyó CORRESPONDENCE Work Address: Department of Policy Analysis and Public Management Bocconi University 1 Via Roentgen Tel: +39 02 5836 5480 20136 Milano Email: [email protected] EDUCATION 2010 D.Phil. (Ph.D.) in Economic and Social History University of Oxford Thesis: Post-War Reconstruction and the Economic Miracle. The Dynamics of West German Economic Growth during the 1950s and 1960s Supervisor: Dr. Oliver Gant Ext. Examiner: Prof. Albrecht Ritschl (LSE) 2007 M.Phil. in Economic and Social History (Distinction) University of Oxford Dissertation: Reconstruction Revisited. Can the Reconstruction Thesis Explain the West German Economic Miracle? Supervisor: Dr. Oliver Grant 2005 B.Sc. in Economic Diplomacy and International Management (Distinction) Budapest Business School 2000- B.Sc. in Economics and Business 2001 University of Pécs (not completed) 1999 International Baccalaureate Diploma Lester B Pearson United World College of the Pacific Victoria BC, Canada ACADEMIC POSITIONS Since 2014 Assistant Professor, Bocconi University, PAM 2013 – 2014 Assistant Professor, LSE, Economic History Department 2012 – 2013 Lecturer, LSE, Economic History Department – 1 – 2010 – 2012 Post-doctoral research fellow, University of Groningen, Faculty of Economics and Business, Groningen Growth and Development Centre 2010 Junior fellow, Collegium Budapest Institute for Advanced Study TEACHING 2014-2015 Economic History (bachelor), Bocconi 2013-2014 Topics in Quantitative Economic History (master), LSE Historical Analysis of Economic Change (master), LSE The Development and Integration of the World Economy in the 19th and 20th Centuries (master), LSE Theories and Evidence in Economic History (bachelor), LSE 2012-2013 Topics in Quantitative Economic History (master), LSE Theories and Evidence in Economic History (bachelor), LSE 2011-2012 Economic History (master), University of Groningnen I ranked among the top five lecturers of the faculty in the course evaluations and I was nominated for the Lecturer of the Year Award. -

Functions of Mud in Estuarine and Coastal Ecosystems

FunctionsFunctions andand behaviourbehaviour ofof mudmud inin estuarineestuarine andand coastalcoastal ecosystemsecosystems Prof.Prof. Dr.Dr. VictorVictor N.N. dede JongeJonge DScDSc Dept. Ocean Ecosystems, University of Groningen, The Netherlands Dept. Biological Sciences, University of Hull, UK [email protected] to keep 1 warf at place …. 1. A ‘storm surge barrier’ was built, (mainly to dam up Ems river water when a newly built giant cruiser had to float to the sea…) 2. river deepening and canalisation was executed & 3. river dredging takes place continuously Resulting in 3. a tremendous change in the river and estuarine light climate SPM concentration Salinity 1200 35 …. (mg/l) (PSU) 1000 2005-2006 30 25 800 20 600 1975-1976 15 400 10 200 5 0 0 0 20406080100120 distance from Herbrum (km) SPM 1975-1976 SPM 2005-2006 salinity 1975-1976 salinity 2005-2006 Oxygen 10.0 concentration (mg/l) 8.0 6.0 No fish species 4.0 can take this barrier 2.0 2.5 mg/l 0.0 0 200 400 600 800 1000 1200 Thanks to N-Ports Emden, (Rewert Wurpts) for help in sampling! River Ems: ‘Yellow river’ Power failure hits Europe [04-11-2006] Danna Avsec Created: 11/5/2006 2:20:56 PMUpdated:11/5/2006 2:21:34 PM 4. About half of W Europe without power for 1 hour because this high voltage power cable over the river Ems was shut down BERLIN (AP) -- A German electric company says it may know the cause of yesterday's chain-reaction blackout that hit parts of Europe.