Biological Control Potential of Miconia Calvescens Using Three Fungal Pathogens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RECORDS of the HAWAII BIOLOGICAL SURVEY for 1995 Part 2: Notes1

RECORDS OF THE HAWAII BIOLOGICAL SURVEY FOR 1995 Part 2: Notes1 This is the second of two parts to the Records of the Hawaii Biological Survey for 1995 and contains the notes on Hawaiian species of plants and animals including new state and island records, range extensions, and other information. Larger, more compre- hensive treatments and papers describing new taxa are treated in the first part of this Records [Bishop Museum Occasional Papers 45]. New Hawaiian Pest Plant Records for 1995 PATRICK CONANT (Hawaii Dept. of Agriculture, Plant Pest Control Branch, 1428 S King St, Honolulu, HI 96814) Fabaceae Ulex europaeus L. New island record On 6 October 1995, Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources, Division of Forestry and Wildlife employee C. Joao submitted an unusual plant he found while work- ing in the Molokai Forest Reserve. The plant was identified as U. europaeus and con- firmed by a Hawaii Department of Agriculture (HDOA) nox-A survey of the site on 9 October revealed an infestation of ca. 19 m2 at about 457 m elevation in the Kamiloa Distr., ca. 6.2 km above Kamehameha Highway. Distribution in Wagner et al. (1990, Manual of the flowering plants of Hawai‘i, p. 716) listed as Maui and Hawaii. Material examined: MOLOKAI: Molokai Forest Reserve, 4 Dec 1995, Guy Nagai s.n. (BISH). Melastomataceae Miconia calvescens DC. New island record, range extensions On 11 October, a student submitted a leaf specimen from the Wailua Houselots area on Kauai to PPC technician A. Bell, who had the specimen confirmed by David Lorence of the National Tropical Botanical Garden as being M. -

Status, Ecology, and Management of the Invasive Plant, Miconia Calvescens DC (Melastomataceae) in the Hawaiian Islands1

Records of the Hawaii Biological Survey for 1996. Bishop 23 Museum Occasional Papers 48: 23-36. (1997) Status, Ecology, and Management of the Invasive Plant, Miconia calvescens DC (Melastomataceae) in the Hawaiian Islands1 A.C. MEDEIROS2, L.L. LOOPE3 (United States Geological Survey, Biological Resources Division, Haleakala National Park Field Station, P.O. Box 369, Makawao, HI 96768, USA), P. CONANT (Hawaii Department of Agriculture, 1428 South King St., P.O. Box 22159, Honolulu, HI 96823, USA), & S. MCELVANEY (Hawaii Natural Heritage Program/The Nature Conservancy of Hawaii, 1116 Smith St., Suite 201, Honolulu, HI 96817, USA) Abstract Miconia calvescens (Melastomataceae), native to montane forests of the neotropics, has now invaded wet forests of both the Society and Hawaiian Islands. This tree, which grows up to 15 m tall, is potentially the most invasive and damaging weed of rainforests of Pacific islands. In moist conditions, it grows rapidly, tolerates shade, and produces abundant seed that is effectively dispersed by birds and accumulates in a large, persistent soil seed-bank. Introduced to the Hawaiian Islands in 1961, M. calvescens appears to threaten much of the biological diversity in native forests receiving 1800–2000 mm or more annual precipitation. Currently, M. calvescens is found on 4 Hawaiian islands— Hawaii, Maui, Oahu, and Kauai. Widespread awareness of this invader began in the early 1990s. Although biological control is being pursued, conventional control techniques (mechanical and chemical) to contain and eradicate it locally are underway. Introduction The effects of biological invasions are increasingly being recognized for their role in degradation of biological diversity worldwide (Usher et al., 1988; D’Antonio & Vitousek, 1992). -

HEAR HNIS Report on Miconia Calvescens

Saturday, March 29, 1997 HNIS Report for Miconia calvescens Page 1 A product of the Hawaiian Ecosystems at Risk Project Miconia calvescens DC. Miconia calvescens, in the melastome family (Melastomataceae), is a tree 4-15 m tall with large (to 80 cm in length), strongly trinerved leaves, dark-green above and purple below. Federal Noxious Weed? N Hawaii State Noxious Weed? Y Federal Seed Act? N Hawaii State Seed Act? N [illustration source: unknown] Native to where : The native range of Miconia calvescens extends from 20 degrees N in Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize to 20 degrees S in Brazil and Argentina (Meyer 1994). The upper elevational limit of the species in its native range is 1830 m in Ecuador (Wurdack 1980). Meyer (1994) determined that the form with very large leaves with purple leaf undersides occurs only in Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, and Costa Rica; specimens examined by Meyer were collected at elevations between 45 m and 1400 m. Native climate : The climate in which Miconia calvescens occurs is tropical montane. Based on its ecology in Tahiti and its occurrence to 1830 m in Ecuador, it appears to pose a threat to all habitats below the upper forest line which receive 1800-2000 mm (75-80 inches) or more of annual precipitation. Biology and ecology : Phenology: Flowering and fruiting of mature trees in Miconia calvescens populations in Hawaii appear to be somewhat synchronized and may be triggered by weather events (drought and/or rain). A single tree can flower/fruit 2-3 times in a year. A single flowering/fruiting event is prolonged, and all stages and mature and immature fruits are often seen on a single tree. -

Ethnobotany and Phytomedicine of the Upper Nyong Valley Forest in Cameroon

African Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology Vol. 3(4). pp. 144-150, April, 2009 Available online http://www.academicjournals.org/ajpp ISSN 1996-0816 © 2009 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper Ethnobotany and phytomedicine of the upper Nyong valley forest in Cameroon T. Jiofack1*, l. Ayissi2, C. Fokunang3, N. Guedje4 and V. Kemeuze1 1Millennium Ecologic Museum, P. O Box 8038, Yaounde – Cameroon. 2Cameron Wildlife Consevation Society (CWCS – Cameroon), Cameroon. 3Faculty of Medicine and Biomedical Science, University of Yaounde I, Cameroon. 4Institute of Agronomic Research for Development, National Herbarium of Cameroon, Cameroon. Accepted 24 March, 2009 This paper presents the results of an assessment of the ethnobotanical uses of some plants recorded in upper Nyong valley forest implemented by the Cameroon wildlife conservation society project (CWCS). Forestry transects in 6 localities, followed by socio-economic study were conducted in 250 local inhabitants. As results, medicinal information on 140 plants species belonging to 60 families were recorded. Local people commonly use plant parts which included leaves, bark, seed, whole plant, stem and flower to cure many diseases. According to these plants, 8% are use to treat malaria while 68% intervenes to cure several others diseases as described on. There is very high demand for medicinal plants due to prevailing economic recession; however their prices are high as a result of prevailing genetic erosion. This report highlighted the need for the improvement of effective management strategies focusing on community forestry programmes and aims to encourage local people participation in the conservation of this forest heritage to achieve a sustainable plant biodiversity and conservation for future posterity. -

Epidemiology of the Invasion by Miconia Calvescens And

J.-Y. Meyer 4 EPIDEMIOLOGY OF THE INVASION BY MICONIA CALVESCENS AND REASONS FOR A SPECTACULAR SUCCESS ÉPIDÉMIOLOGIE DE L’INVASION PAR MICONIA CALVESCENS ET RAISONS D’UN SUCCÈS SPECTACULAIRE JEAN-YVES MEYER1, 2 1 Délégation à la Recherche, B.P. 20981 Papeete, Tahiti, POLYNÉSIE FRANÇAISE. 2 Cooperative National Park Resource Studies Unit, Botany Department, University of Hawai’i at Manoa, Honolulu, HAWAI’I (USA). Miconia calvescens is a small tree native to rainforests of tropical America where it is uncommon. First described around 1850, it was introduced to European tropical greenhouses then distributed to tropical botanical gardens all over the world because of its horticultural success. M.c. was introduced as an ornamental plant in the Society Islands and the Hawaiian Islands and in 25-35 years became a dominant invasive plant in both archipelagoes. Small populations were recently discovered in the Marquesas Islands (Nuku Hiva and Fatu Iva) in 1997. M.c. is also naturalized in private gardens of New Caledonia and Grenada (West Indies), in tropical forests of Sri Lanka, and in the Queensland region in Australia. The survey of the epidemiology of invasion in Tahiti shows that M.c.’s extension was slow but continuous since its introduction in 1937. Hurricanes of 1982-83 played more a role of “revealer” rather than of “detonator” of the invasion. The lag phase observed between the introduction date and the observation of dense populations may be explained by the generation time of M.c.. Several hypothesis may explain the spectacular success of M.c.: (1) the characteristics of the invaded area; (2) the plant’s bio-ecological characteristics; (3) the “facilitation phenomenon“ and the “opportunities“. -

Heptacodium Miconioides

photograph © Peter Del Tredici, Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University An old multi-stemmed specimen of Heptacodium miconioides growing in woodland on Tian Tai Shan, Zhejiang, September 2004, probably the first wild plant ofHeptacodium to be seen by a Western botanist since its discovery by Ernest Wilson in 1907. Heptacodium miconioides Rehder In his last ‘Tree of the Year’, JOHN GRIMSHAW discusses what distinguishes a shrub from a tree and writes about a large shrub introduced to cultivation first in the early twentieth century and again in the late twentieth century, that is rare in the wild. Introduction When the terms of reference for New Trees were drawn up (see pp. 1-2), having agreed that the book would contain only trees, we had to address the deceptive question ‘what is a tree?’ Most of us ‘can recognise a tree when we see one’ and in many ways this is as good an answer as one needs, but when is a woody plant not a tree? When it’s a shrub, of course – but what is a shrub? In the end we adopted the simple definitions that a tree ‘normally [has] a single stem reaching or exceeding 5 m in height, at least in its native habitat. A shrub would normally have multiple woody stems emerging from the base or close to the ground, and would seldom exceed 5 m in height’ (Grimshaw & Bayton 2009). In most cases this served to make a clear distinction, but one of the casualties that fell between the two stools was the Chinese plant Heptacodium miconioides, a significant recent introduction described by theFlora of China (Yang et al. -

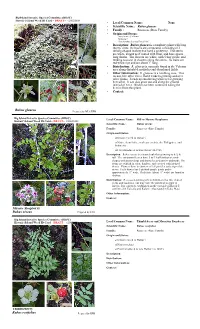

Mysore Raspberry Rubus Niveus Thimbleberry Rubus Rosifolius

Big Island Invasive Species Committee (BIISC) Hawaii‘i Island Weed ID Card – DRAFT– v20030508 • Local/Common Name: None • Scientific Name: Rubus glaucus • Family : Rosaceae (Rose Family) • Origin and Status: – Invasive weed in Hawai‘i – Native to ? – First introduced to into Hawai‘i in ? • Description: Rubus glaucus is a raspberry plant with long thorny vines. Its leaves are compound, consisting of 3 oblong-shaped leaflets that have a pointy tip. The stems are white, almost as if coated with flour, and have sparse long thorns. The flowers are white, with 5 tiny petals, and tending to occur in clusters along the stems. Its fruits are red when ripe and are about 1” long. • Distribution: R. glaucus is currently found in the Volcano area along disturbed roadsides and abandoned fields. • Other Information: R. glaucus is a rambling vine. This means, like other vines, that it tends to grow up and over other plants. It ends up smothering whatever is growing beneath it. It can also grow out and along the ground instead of erect. Birds have been witnessed eating the berries from this plant. • Contact: Rubus glaucus Prepared by MLC/KFB Big Island Invasive Species Committee (BIISC) Local/Common Name: Hill or Mysore Raspberry Hawaii‘i Island Weed ID Card – DRAFT– v20030508 Scientific Name: Rubus niveus Family : Rosaceae (Rose Family) Origin and Status: ?Invasive weed in Hawai‘i ?Native from India, southeastern Asia, the Philippines, and Indonesia ?First introduced to into Hawai‘i in 1965 Description: Rubus niveus is a stout shrub that grows up to 6 ½ ft. tall . The compound leaves have 5 to 9 leaflets that are oval- shaped with pointed tips and thorns located on the underside. -

Miconia Calvescens Global Invasive

FULL ACCOUNT FOR: Miconia calvescens Miconia calvescens System: Terrestrial Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Plantae Magnoliophyta Magnoliopsida Myrtales Melastomataceae Common name miconia (English), cancer vert (English), cancer vert (French), velvet tree (English), purple plague (English), bush currant (English) Synonym Miconia magnifica , Triana 1871 Cyanophyllum magnificum , Groenland 1859 Similar species Summary Miconia calvescens is a small tree native to rainforests of tropical America where it primarily invades treefall gaps and is uncommon. Miconia is now considered one of the most destructive invaders in insular tropical rain forest habitats in its introduced range. It has invaded relatively intact vegetation and displaces native plants on various islands even without habitat disturbance. Miconia has earned itself the descriptions “green cancer of Tahiti\" and “purple plague of Hawaii\". More than half of Tahiti is heavily invaded by this plant. Miconia has a superficial root system which may make landslides more likely. It shades out the native forest understorey and threatens endemic species with extinction. view this species on IUCN Red List Species Description Miconia calvescens is a woody invasive shrubby tree capable of reaching 15m in height; however the majority of specimens in the Society Islands are 6 to 12m tall, with slender, vertical stems (Meyer 1996). The leaves are opposite, elliptic to obovate, usually 60 to 70 cm long (sometimes up to one meter long). A prominent feature of the leaves is the three prominent longitudinal veins. The bicolorous form of the plant has dark green leaves on top with iridescent purple undersides. The inflorescence is a large panicle comprised of 1000 to 3000 white or pink flowers. -

Universidade Estadual De Campinas Instituto De

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE CAMPINAS INSTITUTO DE BIOLOGIA JULIA MEIRELLES FILOGENIA DE Miconia SEÇÃO Miconia SUBSEÇÃO Seriatiflorae E REVISÃO TAXONÔMICA DO CLADO ALBICANS (MELASTOMATACEAE, MICONIEAE) PHYLOGENY OF Miconia SECTION Miconia SUBSECTION Seriatiflorae AND TAXONOMIC REVIEW OF THE ALBICANS CLADE (MELASTOMATACEAE, MICONIEAE) CAMPINAS 2015 UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE CAMPINAS INSTITUTO DE BIOLOGIA Dedico ao botânico mais importante da minha vida: Leléu. Por tudo. AGRADECIMENTOS Agradeço formalmente as agências que concederam as bolsas de estudos sem as quais seria impossível o desenvolvimento deste trabalho ao longo dos últimos 4 anos e meio: CAPES (PNADB e PDSE), CNPQ (programa REFLORA) e NSF (EUA) no âmbito do projeto PBI Miconieae por financiar o trabalho em campo e herbários na Amazônia e também a parte molecular apresentada no Capítulo I. Foram tantas as pessoas que me acompanharam nessa jornada ou que felizmente cruzaram o meu caminho ao decorrer dela, que não posso chegar ao destino sem agradecê-las... O meu maior agradecimento vai ao meu orientador sempre presente Dr. Renato Goldenberg que desde o mestrado confiou em meu trabalho e compartilhou muito conhecimento sobre taxonomia, Melastomataceae e às vezes, até mesmo vida. Sem o seu trabalho, seu profissionalismo e a sua paciência esta tese jamais seria possível. Agradeço pelo tempo que dedicou em me ajudar tanto a crescer como profissional e também como pessoa. Agradeço muito ao meu co-orientador Dr. Fabián Michelangeli por todos os ensinamentos e ajudas no período de estágio sanduíche no Jardim Botânico de Nova Iorque. Todo o seu esforço em reunir e compartilhar bibliografias, angariar recursos e treinar alunos (no quais eu me incluo) tem feito toda a diferença na compreensão da sistemática de Melastomataceae e deixado frutos de inestimável valor. -

Cocoa Beach Maritime Hammock Preserve Management Plan

MANAGEMENT PLAN Cocoa Beach’s Maritime Hammock Preserve City of Cocoa Beach, Florida Florida Communities Trust Project No. 03 – 035 –FF3 Adopted March 18, 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION PAGE I. Introduction ……………………………………………………………. 1 II. Purpose …………………………………………………………….……. 2 a. Future Uses ………….………………………………….…….…… 2 b. Management Objectives ………………………………………….... 2 c. Major Comprehensive Plan Directives ………………………..….... 2 III. Site Development and Improvement ………………………………… 3 a. Existing Physical Improvements ……….…………………………. 3 b. Proposed Physical Improvements…………………………………… 3 c. Wetland Buffer ………...………….………………………………… 4 d. Acknowledgment Sign …………………………………..………… 4 e. Parking ………………………….………………………………… 5 f. Stormwater Facilities …………….………………………………… 5 g. Hazard Mitigation ………………………………………………… 5 h. Permits ………………………….………………………………… 5 i. Easements, Concessions, and Leases …………………………..… 5 IV. Natural Resources ……………………………………………..……… 6 a. Natural Communities ………………………..……………………. 6 b. Listed Animal Species ………………………….…………….……. 7 c. Listed Plant Species …………………………..…………………... 8 d. Inventory of the Natural Communities ………………..………….... 10 e. Water Quality …………..………………………….…..…………... 10 f. Unique Geological Features ………………………………………. 10 g. Trail Network ………………………………….…..………..……... 10 h. Greenways ………………………………….…..……………..……. 11 i Adopted March 18, 2004 V. Resources Enhancement …………………………..…………………… 11 a. Upland Restoration ………………………..………………………. 11 b. Wetland Restoration ………………………….…………….………. 13 c. Invasive Exotic Plants …………………………..…………………... 13 d. Feral -

Low-Maintenance Landscape Plants for South Florida1

ENH854 Low-Maintenance Landscape Plants for South Florida1 Jody Haynes, John McLaughlin, Laura Vasquez, Adrian Hunsberger2 Introduction regular watering, pruning, or spraying—to remain healthy and to maintain an acceptable aesthetic This publication was developed in response to quality. A low-maintenance plant has low fertilizer requests from participants in the Florida Yards & requirements and few pest and disease problems. In Neighborhoods (FYN) program in Miami-Dade addition, low-maintenance plants suitable for south County for a list of recommended landscape plants Florida must also be adapted to—or at least suitable for south Florida. The resulting list includes tolerate—our poor, alkaline, sand- or limestone-based over 350 low-maintenance plants. The following soils. information is included for each species: common name, scientific name, maximum size, growth rate An additional criterion for the plants on this list (vines only), light preference, salt tolerance, and was that they are not listed as being invasive by the other useful characteristics. Florida Exotic Pest Plant Council (FLEPPC, 2001), or restricted by any federal, state, or local laws Criteria (Burks, 2000). Miami-Dade County does have restrictions for planting certain species within 500 This section will describe the criteria by which feet of native habitats they are known to invade plants were selected. It is important to note, first, that (Miami-Dade County, 2001); caution statements are even the most drought-tolerant plants require provided for these species. watering during the establishment period. Although this period varies among species and site conditions, Both native and non-native species are included some general rules for container-grown plants have herein, with native plants denoted by †. -

Native Trees and Plants for Birds and People in the Caribbean Planting for Birds in the Caribbean

Native Trees and Plants for Birds and People in the Caribbean Planting for Birds in the Caribbean If you’re a bird lover yearning for a brighter, busier backyard, native plants are your best bet. The Caribbean’s native trees, shrubs and flowers are great for birds and other wildlife, and they’re also a part of the region’s unique natural heritage. There’s no better way to celebrate the beauty, culture and birds of the Caribbean than helping some native plants get their roots down. The Habitat Around You Habitat restoration sounds like something that is done by governments in national parks, but in reality it can take many forms. Native plants can turn backyards and neighborhood parks into natural habitats that attract and sustain birds and other wildlife. In the Caribbean, land is precious—particularly the coastal areas where so many of us live. Restoring native habitat within our neighborhoods allows us to share the land with native plants and animals. Of course, it doesn’t just benefit the birds. Native landscaping makes neighborhoods more beautiful and keeps us in touch with Caribbean traditions. Why Native Plants? Many plants can help birds and beautify neighborhoods, but native plants really stand out. Our native plants and animals have developed over millions of years to live in harmony: pigeons eat fruits and then disperse seeds, hummingbirds pollinate flowers while sipping nectar. While many plants can benefit birds, native plants almost always do so best due to the partnerships they have developed over the ages. In addition to helping birds, native plants are themselves worthy of celebration.