The Elasticity of the Individual: Early American Historiography and Emerson's Philosophy of History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Roles of Solon in Plato's Dialogues

The Roles of Solon in Plato’s Dialogues Dissertation Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Samuel Ortencio Flores, M.A. Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Bruce Heiden, Advisor Anthony Kaldellis Richard Fletcher Greg Anderson Copyrighy by Samuel Ortencio Flores 2013 Abstract This dissertation is a study of Plato’s use and adaptation of an earlier model and tradition of wisdom based on the thought and legacy of the sixth-century archon, legislator, and poet Solon. Solon is cited and/or quoted thirty-four times in Plato’s dialogues, and alluded to many more times. My study shows that these references and allusions have deeper meaning when contextualized within the reception of Solon in the classical period. For Plato, Solon is a rhetorically powerful figure in advancing the relatively new practice of philosophy in Athens. While Solon himself did not adequately establish justice in the city, his legacy provided a model upon which Platonic philosophy could improve. Chapter One surveys the passing references to Solon in the dialogues as an introduction to my chapters on the dialogues in which Solon is a very prominent figure, Timaeus- Critias, Republic, and Laws. Chapter Two examines Critias’ use of his ancestor Solon to establish his own philosophic credentials. Chapter Three suggests that Socrates re- appropriates the aims and themes of Solon’s political poetry for Socratic philosophy. Chapter Four suggests that Solon provides a legislative model which Plato reconstructs in the Laws for the philosopher to supplant the role of legislator in Greek thought. -

Heroic Individualism: the Hero As Author in Democratic Culture Alan I

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2006 Heroic individualism: the hero as author in democratic culture Alan I. Baily Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Baily, Alan I., "Heroic individualism: the hero as author in democratic culture" (2006). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1073. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1073 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. HEROIC INDIVIDUALISM: THE HERO AS AUTHOR IN DEMOCRATIC CULTURE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Political Science by Alan I. Baily B.S., Texas A&M University—Commerce, 1999 M.A., Louisiana State University, 2003 December, 2006 It has been well said that the highest aim in education is analogous to the highest aim in mathematics, namely, to obtain not results but powers , not particular solutions but the means by which endless solutions may be wrought. He is the most effective educator who aims less at perfecting specific acquirements that at producing that mental condition which renders acquirements easy, and leads to their useful application; who does not seek to make his pupils moral by enjoining particular courses of action, but by bringing into activity the feelings and sympathies that must issue in noble action. -

Dirk Held on Eros Beauty and the Divine in Plato

Nina C. Coppolino, editor ARTICLES & NOTES New England Classical Journal 36.3 (2009) 155-167 Eros, Beauty, and the Divine in Plato Dirk t. D. Held Connecticut College ontemporary intellectual culture is diffident, perhaps hostile, towards the transcendent aspects of Plato’s metaphysics; instead, preference is given to the openness and inconclusiveness of CSocratic inquiry. But it is not possible to distinguish clearly between the philosophy of Socrates and Plato. This essay argues first that Socrates does more than inquire: he enlarges the search for truth with attention to erotics. It further contends that Plato’s transformative vision of beauty and the divine directs the soul, also through erotics, to truth not accessible to syllogisms alone. We must therefore acknowledge that Plato’s philosophy relies at times on affective and even supra-rational means. Debate over the function of philosophy for Socrates and Plato arose immediately following the latter’s death. The early Academy discussed the mode and intent of reason for Socrates and Plato in terms of whether it was best characterized as skepticism or dogmatism. The issue remains pertinent to the present discussion of how Plato intends mortals both to live a life of reason and strive for the divine which is beyond the normal grasp of reason. What we regard as the traditional “Socratic question” arose in the early nineteenth century from studies of Plato by the Protestant theologian and philosopher, Friedrich Schleiermacher. The phrase stands for the attempt to winnow out an historical figure from the disparate accounts of Socrates found in Plato, Xenophon, and Aristophanes. -

A Higher Sphere of Thought”

“A HIGHER SPHERE OF THOUGHT”: EMERSON’S USE OF THE EXEMPLUM AND EXEMPLUM FIDEI By CHARLA DAWN MAJOR Master of Arts Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 1995 Bachelor of Arts The University of Texas at Dallas Richardson, Texas 1990 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 2005 “A HIGHER SPHERE OF THOUGHT”: EMERSON’S USE OF THE EXEMPLUM AND EXEMPLUM FIDEI Dissertation Approved: _______________Jeffrey Walker________________ Dissertation Adviser _____________William M. Decker_______________ _______________Edward Jones________________ ________________L. G. Moses_________________ ______________A. Gordon Emslie_______________ Dean of the Graduate College ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my sincere appreciation to my advisor, Dr. Jeffrey Walker, for his guidance, support, and friendship, not only during the considerable duration of this work but throughout the entire course of my graduate studies here at Oklahoma State University. No one could ask for a better teacher, advisor, mentor, and friend, and I have gained immeasurably from this long association. I consider myself extremely fortunate and blessed. My gratitude extends to my committee members. Dr. William Decker has been a continual source of guidance and resources and has consistently perpetuated my interest in both this subject and literary period. Dr. Edward Jones, who has been there from the very beginning, has been a great source of guidance, assistance, encouragement, and friendship and has demonstrated a welcome propensity for being available to me at critical points in my education. And Dr. L. G. Moses, my most recent acquaintance, has offered a unique intelligence and wit that made this dissertation a truly enjoyable learning experience. -

What Was the Cause of Nietzsche's Dementia?

PATIENTS What was the cause of Nietzsche’s dementia? Leonard Sax Summary: Many scholars have argued that Nietzsche’s dementia was caused by syphilis. A careful review of the evidence suggests that this consensus is probably incorrect. The syphilis hypothesis is not compatible with most of the evidence available. Other hypotheses – such as slowly growing right-sided retro-orbital meningioma – provide a more plausible fit to the evidence. Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) ranks among the paintings had to be removed from his room so that most influential of modern philosophers. Novelist it would look more like a temple2. Thomas Mann, playwright George Bernard Shaw, On 3 January 1889, Nietzsche was accosted by journalist H L Mencken, and philosophers Martin two Turinese policemen after making some sort of Heidegger, Karl Jaspers, Jacques Derrida, and public disturbance: precisely what happened is not Francis Fukuyama – to name only a few – all known. (The often-repeated fable – that Nietzsche acknowledged Nietzsche as a major inspiration saw a horse being whipped at the other end of the for their work. Scholars today generally recognize Piazza Carlo Alberto, ran to the horse, threw his Nietzsche as: arms around the horse’s neck, and collapsed to the ground – has been shown to be apocryphal by the pivotal philosopher in the transition to post-modernism. Verrecchia3.) Fino persuaded the policemen to There have been few intellectual or artistic movements that have 1 release Nietzsche into his custody. not laid a claim of some kind to him. Nietzsche meanwhile had begun to write brief, Nietzsche succumbed to dementia in January bizarre letters. -

Margaret Fuller and the Peabody Sisters

The Emerson Circle of the Unitarian Society of Ridgewood Cordially invites you to a talk by Award-winning author Megan Marshall Margaret Fuller and the Peabody Sisters: The Origins of an American Women’s Movement in Unitarian-Transcendentalism A Talk by Megan Marshall Thursday, February 12th at 7:00pm We tend to think of American feminism beginning with the suffrage movement, but where did those ideas come from? New England women provided an overlooked impetus in a groundswell of “Conversation” and writing provoked by the questioning era of 1840s Transcendentalism. In fact, Margaret Fuller’s Woman in the Nineteenth Century (1853) not only set the stage for activism in its own time, it anticipated 20th- and 21st-century critiques of “socially constructed” gender roles for both women and men. Male and female “are perpetually passing into one another,” Fuller wrote, “there is no wholly masculine man, no purely feminine woman”—a statement that was shocking in its time and still reverberates today. Award-winning author Megan Marshall will discuss her two prize-winning biographies, her research and fascination with these founders of American feminism whose network of friends (and husbands!) included Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Horace Mann. Megan Marshall is the author of Margaret Fuller: A New American Life, winner of the 2014 Pulitzer Prize in Biography, and The Peabody Sisters: Three Women Who Ignited American Romanticism, winner of the Francis Parkman Prize, the Mark Lynton History Prize, and finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in 2006. She is currently the Gilder Lehrman Fellow at the Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers of the New York Public Library, and has held fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University. -

Dialogue Between Confucius and Socrates: Norms of Rhetorical Constructs in Their Dialogical Form and Dialogic Imagination

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1998 Dialogue Between Confucius and Socrates: Norms of Rhetorical Constructs in Their Dialogical Form and Dialogic Imagination. Bin Xie Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Xie, Bin, "Dialogue Between Confucius and Socrates: Norms of Rhetorical Constructs in Their Dialogical Form and Dialogic Imagination." (1998). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6717. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6717 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter free, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Mencius on Becoming Human a Dissertation Submitted To

UNIVERSITY OF HAWNI LIBRARY MENCIUS ON BECOMING HUMAN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN PHILOSOPHY DECEMBER 2002 By James P. Behuniak Dissertation Committee: Roger Ames, Chairperson Eliot Deutsch James Tiles Edward Davis Steve Odin Joseph Grange 11 ©2002 by James Behuniak, Jr. iii For my Family. IV ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS With support from the Center for Chinese Studies at the University of Hawai'i, the Harvard-Yenching Institute at Harvard University, and the Office of International Relations at Peking University, much of this work was completed as a Visiting Research Scholar at Peking Univeristy over the academic year 2001-2002. Peking University was an ideal place to work and I am very grateful for the support of these institutions. I thank Roger Ames for several years of instruction, encouragement, generosity, and friendship, as well as for many hours of conversation. I also thank the Ames family, Roger, Bonney, and Austin, for their hospitality in Beijing. I thank Geir Sigurdsson for being the best friend that a dissertation writer could ever hope for. Geir was also in Beijing and read and commented on the manuscript. I thank my committee members for comments and recommendations submitted over the course of this work. lowe a lot to Jim Tiles for prompting me to think through the subtler components of my argument. I take full responsibility for any remaining weaknesses that carry over into this draft. I thank my additional member, Joseph Grange, who has been a mentor and friend for many years. -

THEME and SUBJECT MATTER in Francis Parkman’S the Old Régime in Canada

FEATURES THEME AND SUBJECT MATTER In Francis Parkman’s The Old Régime in Canada IntroductIon Edgardo Medeiros da Silva University of Lisbon This paper examines the failure of France to establish the basis Portugal of a well-regulated political community in North America as conveyed by the American historian Francis Parkman in Part Four of his History of France and England in North America, entitled The Old Régime in Canada (1874). Parkman’s choice of theme and subject matter for his History points to differences between the English and French settlements, which portray, as has been suggested, ‘the struggle between France and England as a heroic contest between rival civilizations with wilderness as a modifying force’ (Jacobs, 2001: 582). This struggle and these differences reflect a deep-seated cultural and political bias against colonial France on the part of New Eng- land historians that stretch as far back as Joseph Dennie’s Portfolio and Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790). It is my contention that Part Four of Parkman’s History, informed by the ‘Teutonic germ’ commonly associated with the historiog- raphy of New England’s nineteenth-century Romantic or literary historians, provides us with an account of the colonization of New France which sheds some light on the colonial beginnings of New England as well. Not infrequently, in fact, Parkman’s historical nar- rative on New France is juxtaposed with that of New England, one providing a sort of backdrop for the cultural and political make-up of the other. The son of a Unitarian minister, Francis Parkman (1823–1893) was born in Boston, Massachusetts. -

Emerson's Hidden Influence: What Can Spinoza Tell the Boy?

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Philosophy Honors Theses Department of Philosophy 6-15-2007 Emerson's Hidden Influence: What Can Spinoza Tell the Boy? Adam Adler Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/philosophy_hontheses Recommended Citation Adler, Adam, "Emerson's Hidden Influence: What Can Spinoza Tell the Boy?." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2007. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/philosophy_hontheses/2 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Philosophy at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EMERSON’S HIDDEN INFLUENCE: WHAT CAN SPINOZA TELL THE BOY? by ADAM ADLER Under the Direction of Reiner Smolinski and Melissa Merritt ABSTRACT Scholarship on Emerson to date has not considered Spinoza’s influence upon his thought. Indeed, from his lifetime until the twentieth century, Emerson’s friends and disciples engaged in a concerted cover-up because of Spinoza’s hated name. However, Emerson mentioned his respect and admiration of Spinoza in his journals, letters, lectures, and essays, and Emerson’s thought clearly shows an importation of ideas central to Spinoza’s system of metaphysics, ethics, and biblical hermeneutics. In this essay, I undertake a biographical and philosophical study in order to show the extent of Spinoza’s influence on Emerson and -

Social Studies TEKS Streamlining Historical Figures List Revised Oct

Social Studies TEKS Streamlining Historical Figures List revised Oct. 2018 Current Proposed Including, or Grade/Course Historical Figure SE SE Such as Grade/Course First name Last name 442nd Regimental Combat Grade 5 5C Such as Team Grade 2 13B 10B Abigail Adams Such as Grade 8 4B Abigail Adams Including Grade 5 2B John Adams Including Grade 8 4B John Adams Including U.S. Government 1D John Adams Including Grade 8 7D John Quincy Adams Including Grade 5 2B Samuel Adams Including Grade 8 4B Samuel Adams Including Grade 5 5C Jane Addams Such as U.S. History Since 1877 26D 5B Jane Addams Such as Grade 1 2B Richard Allen Such as Grade 7 2B Alonso Álvarez de Pineda Such as Grade 3 8E Wallace Amos Such as Grade 5 5C Susan B. Anthony Such as Grade 8 22B Susan B. Anthony Such as U.S. History Since 1877 5B Susan B. Anthony Such as World History 20C 19C Thomas Aquinas Such as World History 27E 26E Archimedes Such as Grade 8 4B James Armistead Including Grade 5 23A 22A Neil Armstrong Such as Grade 3 8E Mary Kay Ash Such as Grade 8 4B Crispus Attucks Including Grade 8 26A John James Audubon Such as Grade 7 2E Moses Austin Including Kindergarten 2A 2 Stephen F. Austin Including Grade 4 2E Stephen F. Austin Including Grade 7 2E Stephen F. Austin Including Grade 7 18B 17B Kay Bailey Hutchison Such as U.S. History Since 1877 26F 25E Vernon J. Baker Such as Grade 4 17D James A. -

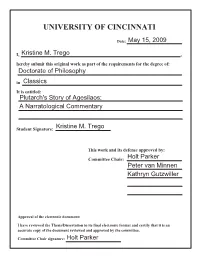

University of Cincinnati

U UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: May 15, 2009 I, Kristine M. Trego , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctorate of Philosophy in Classics It is entitled: Plutarch's Story of Agesilaos; A Narratological Commentary Student Signature: Kristine M. Trego This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Holt Parker Peter van Minnen Kathryn Gutzwiller Approval of the electronic document: I have reviewed the Thesis/Dissertation in its final electronic format and certify that it is an accurate copy of the document reviewed and approved by the committee. Committee Chair signature: Holt Parker Plutarch’s Story of Agesilaos; A Narratological Commentary A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in the Department of Classics of the College of Arts and Sciences 2009 by Kristine M. Trego B.A., University of South Florida, 2001 M.A. University of Cincinnati, 2004 Committee Chair: Holt N. Parker Committee Members: Peter van Minnen Kathryn J. Gutzwiller Abstract This analysis will look at the narration and structure of Plutarch’s Agesilaos. The project will offer insight into the methods by which the narrator constructs and presents the story of the life of a well-known historical figure and how his narrative techniques effects his reliability as a historical source. There is an abundance of exceptional recent studies on Plutarch’s interaction with and place within the historical tradition, his literary and philosophical influences, the role of morals in his Lives, and his use of source material, however there has been little scholarly focus—but much interest—in the examination of how Plutarch constructs his narratives to tell the stories they do.