Mono ENGLISH

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism, Revised Edition

REVISED EDITION John Powers ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 1 Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 2 ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 3 Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism revised edition by John Powers Snow Lion Publications ithaca, new york • boulder, colorado ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 4 Snow Lion Publications P.O. Box 6483 • Ithaca, NY 14851 USA (607) 273-8519 • www.snowlionpub.com © 1995, 2007 by John Powers All rights reserved. First edition 1995 Second edition 2007 No portion of this book may be reproduced by any means without prior written permission from the publisher. Printed in Canada on acid-free recycled paper. Designed and typeset by Gopa & Ted2, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Powers, John, 1957- Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism / by John Powers. — Rev. ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN-13: 978-1-55939-282-2 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-55939-282-7 (alk. paper) 1. Buddhism—China—Tibet. 2. Tibet (China)—Religion. I. Title. BQ7604.P69 2007 294.3’923—dc22 2007019309 ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 5 Table of Contents Preface 11 Technical Note 17 Introduction 21 Part One: The Indian Background 1. Buddhism in India 31 The Buddha 31 The Buddha’s Life and Lives 34 Epilogue 56 2. Some Important Buddhist Doctrines 63 Cyclic Existence 63 Appearance and Reality 71 3. Meditation 81 The Role of Meditation in Indian and Tibetan Buddhism 81 Stabilizing and Analytical Meditation 85 The Five Buddhist Paths 91 4. -

Spring/Summer 2010 in This Issue

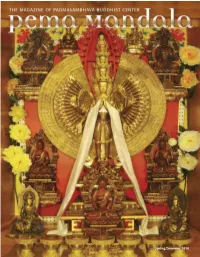

Spring/Summer 2010 In This Issue 1 Letter from the Venerable Khenpo Rinpoches 2 Brilliant Lotus Garland of Glorious Wisdom A Glimpse into the Ancient Lineage of Khenchen Palden Volume 9, Spring/Summer 2010 Sherab Rinpoche A Publication of 6 Entrusted: The Journey of Khenchen Rinpoche’s Begging Bowl Padmasambhava Buddhist Center 9 Fulfillment of Wishes: Nyingma Lineage of Tibetan Buddhism Eight Great Stupas & Five Dhyani Buddhas Founding Directors 12 How I Met the Khenpo Rinpoches Ven. Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche Ven. Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal Rinpoche 14 Schedule of Teachings 16 The Activity Samayas of Anuyoga Ani Lorraine, Co-Editor An Excerpt from the 2009 Shedra, Year 7: Anuyoga Pema Dragpa, Co-Editor Amanda Lewis, Assistant Editor 18 Garland of Views Pema Tsultrim, Coordinator Beth Gongde, Copy Editor 24 The Fruits of Service Michael Ray Nott, Art Director 26 2009 Year in Review Sandy Mueller, Production Editor PBC and Pema Mandala Office For subscriptions or contributions to the magazine, please contact: Padma Samye Ling Attn: Pema Mandala 618 Buddha Highway Sidney Center, NY 13839 (607) 865-8068 [email protected] Pema Mandala welcomes all contributions submitted for consideration. All accepted submissions will be edited appropriately for Cover: 1,000 Armed Chenrezig statue with the publication in a magazine representing the Five Dhyani Buddhas in the Shantarakshita Padmasambhava Buddhist Center. Library at Padma Samye Ling Please email submissions to Photographed by Amanda Lewis [email protected]. © Copyright 2010 by Padmasambhava Buddhist Center International. Material in this publication is copyrighted and may not be reproduced by photocopy or any other means without obtaining written permission from the publisher. -

Qt70g9147s.Pdf

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Previously Published Works Title Tibetan Buddhist dream yoga and the limits of Western Psychology. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/70g9147s ISBN 9781440829475 Author ROSCH, E Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California In R. Hurd & K. Bulkeley (Eds.) Lucid dreaming: New perspectives on consciousness in sleep. Volume 2: Religion, creativity, and culture. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger, 2014, pp 1-22. Tibetan Buddhist Dream Yoga and the Limits of Western Psychology Eleanor Rosch Department of Psychology University of California, Berkeley “Look to your experience in sleep to discover whether or not you are truly awake.”1 The Buddha has been called both The Awakened One and The Enlightened One, and both of these qualities are evoked by the word lucid in the way that we now use it to refer to lucid dreaming. However, the uses to which lucidity in dreams has been put by the West is limited and relatively superficial compared to lucidity in dreams, dreamless sleep, daily life, and even death in the practices of Tibetan Vajrayana Buddhism. As the Tibetan teacher Tendzin Wangyal puts it, “Dream practice is not just for personal growth or to generate interesting experiences. It is part of the spiritual path and its results should affect all aspects of life by changing the practitioner’s identity, and the relationship between the practitioner and the world.”2 What does that mean? How can it be accomplished? And what implications might these practices have for our psychology and for Western science more generally? In this chapter I will address such questions, first by discussing the Buddhist material, and then by examining the ways in which the effects of lucidity in Tibetan Buddhist practitioners challenge basic assumptions about bodies and minds in Western science. -

The Practice of the SIX YOGAS of NAROPA the Practice of the SIX YOGAS of NAROPA

3/420 The Practice of THE SIX YOGAS OF NAROPA The Practice of THE SIX YOGAS OF NAROPA Translated, edited and introduced by Glenn H. Mullin 6/420 Table of Contents Preface 7 Technical Note 11 Translator's Introduction 13 1 The Oral Instruction of the Six Yogas by the Indian Mahasiddha Tilopa (988-1069) 23 2 Vajra Verses of the Whispered Tradition by the Indian Mahasiddha Naropa (1016-1100) 31 3 Notes on A Book of Three Inspirations by Jey Sherab Gyatso (1803-1875) 43 4 Handprints of the Profound Path of the Six Yogas of Naropa: A Source of Every Realiza- tion by Gyalwa Wensapa (1505-1566) 71 8/420 5 A Practice Manual on the Six Yogas of Naropa: Taking the Practice in Hand by Lama Jey Tsongkhapa (1357-1419) 93 6 The Golden Key: A Profound Guide to the Six Yogas of Naropa by the First Panchen Lama (1568-1662) 137 Notes 155 Glossary: Tibetan Personal and Place Names 167 Texts Quoted 171 Preface Although it is complete in its own right and stands well on its own, this collection of short commentaries on the Six Yogas of Naropa, translated from the Tibetan, was originally conceived of as a companion read- er to my Tsongkhapa's Six Yogas of Naropa (Snow Lion, 1996). That volume presents one of the greatest Tibetan treatises on the Six Yogas system, a text composed by the Tibetan master Lama Jey Tsongkhapa (1357-1419)-A Book of Three Inspirations: A Treatise on the Stages of Training in the Profound Path of Naropa's Six Yogas (Tib. -

Dream-Yoga.Pdf

Dream Yoga Gnostic Muse Drea m Yoga is the practice of using mantras, prayers, and watchfulness to awaken the consciousness here and now, and thereby also awaken in dreams. Dream experiences can have a spectrum of consciousness. There are dreams that are vivid and lucid, dreams where we are awake but without agency to act, and dreams where we are fully conscious and can direct our experience in the astral plane. Out-of-body experiences, astral travel and lucid dreaming are terms for the same thing: consciousness in the astral world. Dream Yoga is Universal in all Religious Traditions https://www.gnosticmuse.com Dream Yoga Gnostic Muse “Now when the bardo of dreams is dawning upon me, I will abandon the corpse-like sleep of careless ignorance, and let my thoughts enter their natural state without distraction; controlling and transforming dreams in luminosity; I will not sleep like any animal but unify sleep and practice.” -Tibetan Book of the Dead: Main Verses of the Six Bardos https://www.gnosticmuse.com Dream Yoga Gnostic Muse Once upon a time, I, Chuang Chou, dreamt I was a butterfly, fluttering hither and thither, to all intents and purposes a butterfly. I was conscious only of my happiness as a butterfly, unaware that I was Chou. Soon I awaked, and there I was, veritably myself again. Now I do not know whether I was then a man dreaming I was a butterfly, or whether I am now a butterfly, dreaming I am a man. Between a man and a butterfly there is necessarily a distinction. -

Life Is but a Dream: Dream Yoga in Tibetan Buddhist Tantra

Life is But a Dream: Dream Yoga in Tibetan Buddhist Tantra Bruce Knauft Department of Anthropology Emory University For presentation at the Society for Psychological Anthropology Meetings Albuquerque, NM April 4-7, 2019 In the session, “New Directions in the Anthropology and Psychology of Dreaming” Organized by Jeanette Mageo & Robin Sheriff The thesis of my paper – evolving out the abstract submitted months ago – is that our lingering ethnocentric reification of “dreaming” as not just distinct from but the opposite of “waking” – dream consciousness versus waking consciousness – elides and occludes much power and value in and across mental states that include dreaming. There is arguably a strong connection if not continuum across mental states that may include waking thought projections, day dreaming, somnolence, and states of lucid consciousness that can include dreaming, spirit possession or shamanism, and the impact of eXternally induced hallucinogenic visions and eXperiences. Especially when viewed in comparative cultural conteXt, there is frequently a productive if not conversational continuum across diverse types and states of consciousness. While this is a simple and obvious point – and one that psychological anthropologists have been at the forefront of making for many years, it can be useful to reassert and rediscover it in our current conteXt of dreams and dreaming. Like the critique of the Western split between mind and body, as well as that between mind and brain, critiques once made don’t preclude the scholarly tendency to reproduce them over time, reinforcing their continuing limitations of perspective. Like other constraining Western reifications and polarized conceptualizations, that between waking daytime consciousness and the nighttime consciousness of dreaming can be productively reconsidered. -

Legitimation and Innovation in the Tibetan Buddhist Chöd Tradition

Making the Old New Again and Again: Legitimation and Innovation in the Tibetan Buddhist Chöd Tradition Michelle Janet Sorensen Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 Michelle Janet Sorensen All rights reserved ABSTRACT Making the Old New Again and Again: Legitimation and Innovation in the Tibetan Buddhist Chöd Tradition Michelle Janet Sorensen My dissertation offers a revisionary history of the early development of Chöd, a philosophy and practice that became integral to all Tibetan Buddhist schools. Recent scholars have interpreted Chöd ahistorically, considering it as a shamanic tradition consonant with indigenous Tibetan practices. In contrast, through a study of the inception, lineages, and praxis of Chöd, my dissertation argues that Chöd evolved through its responses to particular Buddhist ideas and developments during the “later spread” of Buddhism in Tibet. I examine the efforts of Machik Labdrön (1055-1153), the founder of Chöd and the first woman to develop a Buddhist tradition in Tibet, simultaneously to legitimate her teachings as authentically Buddhist and to differentiate them from those of male charismatic teachers. In contrast to the prevailing scholarly view which exoticizes central Chöd practices—such as the visualized offering of the body to demons—I examine them as a manifestation of key Buddhist tenets from the Prajñāpāramitā corpus and Vajrayāna traditions on the virtue of generosity, the problem of ego-clinging, and the ontology of emptiness. Finally, my translation and discussion of the texts of the Third Karmapa Rangjung Dorjé (1284-1339), including the earliest extant commentary on a text of Machik Labdrön’s, focuses on new ways to appreciate the transmission and institutionalization of Chöd. -

Dream Yoga and the Practice of Natural Light Free Ebook

FREEDREAM YOGA AND THE PRACTICE OF NATURAL LIGHT EBOOK Namkhai Norbu,Michael Katz | 168 pages | 05 Aug 2002 | Shambhala Publications Inc | 9781559391610 | English | Ithaca, United States Dream Yoga and the Practice of Natural Light We are shipping to all international locations. Learn more here about our many free resources and special digital offers. This revised and enlarged edition includes additional material from a profoiuid and personal Dzogchen book which Chogyal Namkhai Norbu has been writing for many years. This Dream Yoga and the Practice of Natural Light expands and deepens the first edition's emphasis on specific exercises to develop awareness within the dream and sleep states. Rinpoche gives instructions for developing clarity within the sleep and dream states. He goes beyond the practices of lucid dreaming that have been popularized in the West, by presenting methods for guiding dream states that are part of a broader system for enhancing self-awareness called Dzogchen. In this tradition, the development of lucidity in the dream state is understood in the context of generating greater awareness for the ultimate purpose of attaining liberation. Also included in this book is a text written by Mipham, the nineteenth- century master of Dzogchen, which offers additional insights into this extraordinary form of meditation and awareness. Chogyal Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche is one of the greatest Tibetan meditation masters and scholars teaching in the West today. His luminous Dream Yoga teachings are invaluable. I myself read this book with great Dream Yoga and the Practice of Natural Light, and recommend it to my own students. Chogyal Namkhai Norbu is a Tibetan master of the Dzogchen tradition. -

An Introduction to Mahamudra Meditation

An Introduction to Mahamudra Meditation By The Venerable Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche Geshe Lharampa Translated by Yeshe Gyamtso Transcribed by Annelie Speidelsbach Copyright © 2001 by Thrangu Rinpoche All rights reserved. No part of this book, either text or art, may be reproduced in any form, electronic or otherwise, without written permission from Thrangu Rinpoche or Namo Buddha Publications. Namo Buddha Publications P. O. Box 1083 Crestone, CO 81131 Phone: (719) 256-5367 Email: [email protected] Thrangu Rinpoche’s web site: www.rinpoche.com These teachings were given in Edmonton, Canada June 25 - 27, 1999 Note We have italicized the technical words the first time that they appear to alert the reader that their definition can be found in the Glossary. To assist the practitioner the Tibetan words are given as they are pronounced, not spelled in Tibetan. Acknowledgments We would like to thank Yeshe Gyamtso for translating these teachings and for Annelie Speidelsbach who transcribed these teachings. Chapter 1 Mahamudra Meditation Generally speaking, when I travel I give many teachings on meditation. I try to talk mostly about the practice of Mahamudra meditation. My hope is that by doing so I will give people something that will actually help them work with their own mind. The reason I teach Mahamudra is that when the Sixteenth Karmapa came to the West, and was asked what practice would be appropriate for present western culture, he said that he felt the most appropriate meditation practice to pursue was Mahamudra. THE 84 MAHASIDDHAS Since dharma practitioners have innumerable varieties of lifestyles, the practice that they engage in needs to be something that can fit into any lifestyle. -

Here Is the Panchen Lama Now? by ALEJANDRO CHAOUL-REICH

Snow Lion Publications wLionPO Box 6483, Ithaca, NY 14851 607-273-8519 Orders: 800-950-0313 Volume 16, Number 1 WINTER 2001 NEWSLETTER ISSN 1059-3691 BN:86605 3697 & CATALOG SUPPLEMENT SPINNING THE MAGICAL WHEEL Where is the Panchen Lama now? by ALEJANDRO CHAOUL-REICH Introduction—Tibetan Yogas by ROBIN GARTHWATT control the Tibetan people by direct- There is a growing interest in Tibetan The sun sets, the moon begins its ing the selection and upbringing of physical yogas in the West. Yoga arc across the sky and a young boy the leadership. Journal has published two articles spends another day in no man's land. Historically, the Panchen Lama on Tibetan yoga in the last year Isolated from his people, his teach- has been instrumental in helping con- alone; one on the types of Tibetan ers, his birthright, Gedhun Choekyi firm the reincarnation of the Dalai yogas that have come to the United Nyima, the 11th Panchen Lama is Lama and vice-versa Thus, by con- States, and another on a book, The still trapped in a political game of cat trolling the Panchen Lama, the Chi- Dalai Lama's Secret Temple, which and mouse. nese government believes they have describes the paintings of the secret And although the Chinese gov- power over the selection of the next temple of the Dalai Lama in Lhasa, ernment would like the issue of Dalai Lama. The current Dalai Lama behind the famous Potala Palace. the Panchen Lama to go away, this categorically denies that assump- Many of these paintings are poses particularly nasty situation, like the tion. -

Download Download

Book Review I J o D R Book review: Dreaming Yourself Awake by B. Alan Wallace Tadas Stumbrys Institute of Sports and Sports Sciences, Heidelberg University, Germany Summary. This book by a Tibetan Buddhist scholar and practitioner aims to integrate two approaches to dream practice: Lucid dreaming and dream yoga. Wallace introduces methods promoting lucidity from both traditions and fosters further dialogue between East and West. Wallace, B. A. (2012). Dreaming Yourself Awake – Lucid Dreaming and Tibetan Dream Yoga for Insight and Transforma- tion. Boston: Shambhala. Keywords: lucid dreaming; dream yoga This book aims to bridge East and West: to join the findings tice the awareness of awareness. Although parallels be- of the scientific lucid dream research from the West with tween meditation and lucidity have been suggested before the wisdom of the Tibetan dream yoga tradition from the (Gackenbach & Bosveld, 1990; Hunt & Ogilvie, 1989; Hunt, East. And the author, B. Alan Wallace, seems to have all 1989; Stumbrys, 2011), empirical research on whether or the credentials to do that. The most recent efforts to pres- not meditation practices are effective in increasing lucid ent the dream yoga tradition to the West were mainly lim- dream ability is lacking (cf. Stumbrys, Erlacher, Schädlich, & ited to Tibetan teachers (e.g. Norbu, 1992, Wangyal, 1998), Schredl, 2012), but would be very welcomed indeed. who were not well acquainted with modern lucid dream re- In addition to meditation practices, Wallace also de- search, or Western researchers (e.g. LaBerge, 2003), who scribes a number of “Western” lucid dreaming methods, lacked extensive training in the Tibetan Buddhism tradition. -

Ancient Tibetan Dream Wisdom Tarab Tulku Rinpoche1

Tarab Institute International 4 July 2013 Ancient Tibetan Dream Wisdom Tarab Tulku Rinpoche1, 4 July 2013 Keywords: Unity in Duality – Dream 1Geshe Lharampa/Phd, Founder Unity in Duality and Tarab Institute International Correspondence: [email protected] Tibetan dream work has an extensive history protectors. As a Tibetan child I simply listened to incorporating pre-Buddhist folk religion, Bon and adults talking about spirits and protectors, I took Buddhism. Tibetans who experience problems part in their rituals from the age of one, where I with Nature spirits use dreams to resolve these, in was enthroned in my monastery in Kongpo as the addition to consulting with Oracles. The use of reincarnation Lama Tarab and from the age of spirits and oracles is entrenched in Tibetan four I started to lead those rituals, one of the roles culture; there is a State Oracle, and each person of the Lama. It was therefore natural for me to has a birth spirit or protector spirit, which helps deal with spirits both in Dreams and in the waken the person throughout his or her life. When people state. were disturbed by a negative spirit, they would call on their helping spirit, and whether this When I was ten or eleven my main teacher, occurred in the waken state or dream state made Ven. Kensur Gyaltsen Rinpoche, started to little difference. This facility of working with formally train me and three other Lamas in how to spirits in the dream state still prevails amongst work with the dream state. He did not teach us the Tibetans today.