This Opinion Is Not a Precedent of the Ttab

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entry List - Numerical Charlotte Motor Speedway 36Th Annual Drive for the Cure 300 Presented by Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina

Entry List - Numerical Charlotte Motor Speedway 36th Annual Drive for the Cure 300 presented by Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina Provided by NASCAR Statistics - Fri, October 06, 2017 @ 03:14 PM Eastern Car Driver Team Name Owner Crew Chief 1 0 Garrett Smithley teamjdmotorsports.com Chevrolet Gary Cogswell Wayne Setterington, Jr 2 00 Cole Custer # (P) Haas Automation Ford Gene Haas Jeff Meendering 3 01 Harrison Rhodes teamjdmotorsports.com Chevrolet Johnny Davis Tommy MacHek 4 1 Elliott Sadler (P) OneMain Financial Chevrolet Dale Earnhardt, Jr Kevin Meendering 5 2 Austin Dillon(i) Rheem Chevrolet Richard Childress Nicholas Harrison 6 3 Ty Dillon(i) Advil Chevrolet Richard Childress Matt Swiderski 7 4 Ross Chastain Flex Seal Chevrolet Gary Keller Evan Snider 8 5 Michael Annett (P) TMC Chevrolet Dale Earnhardt, Jr Jason Stockert 9 07 Ray Black II Collins Construction Roofing Chevrolet Bobby Dotter Jason Miller 10 7 Justin Allgaier (P) Advance Auto Parts Chevrolet Kelley Earnhardt-Miller Jason Burdett 11 8 BJ McLeod KeenParts.com/CorvetteParts.net Chevrolet Jessica Smith-McLeod George Ingram 12 9 William Byron # (P) Liberty University Chevrolet Rick Hendrick David Elenz 13 11 Blake Koch (P) LeafFilter Gutter Protection Chevrolet Matthew Kaulig Chris Rice 14 12 Sam Hornish Jr. PPG Ford Roger Penske Brian Wilson 15 13 Timmy Hill OCR Gaz Bar Dodge Danielle Long Sebastian Laforge 16 14 JJ Yeley Pray for Las Vegas/TriStar Motorsports Toyota Mark Smith Wally Rogers 17 15 Reed Sorenson(i) teamjdmotorsports.com Chevrolet Carol Clark Bryan Berry 18 16 Ryan Reed (P) Lilly Diabetes Ford Jack Roush Phil Gould 19 18 Daniel Suarez(i) Juniper Toyota J.D. -

Lead Fin Pos Driver Team Laps Pts Bns Pts Winnings

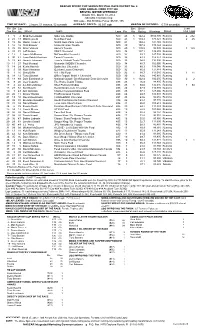

NASCAR SPRINT CUP SERIES OFFICIAL RACE REPORT No. 20 18TH ANNUAL BRICKYARD 400 PRESENTED BY BIGMACHINERECORDS.COM INDIANAPOLIS MOTOR SPEEDWAY Indianapolis, IN - July 31, 2011 2.5-Mile Paved Rectangle 160 Laps - 400 Miles Purse: $9,017,034 TIME OF RACE: 2 hours, 50 minutes, 30 seconds AVERAGE SPEED: 140.762 mph MARGIN OF VICTORY: 0.725 second(s) Fin Str Car Bns Driver Lead Pos Pos No Driver Team Laps Pts Pts Rating Winnings Status Tms Laps 1 15 27 Paul Menard Nibco/Menards Chevrolet 160 47 4 104.0 $373,575 Running 4 21 2 8 24 Jeff Gordon Drive To End Hunger Chevrolet 160 43 1 136.0 358,536 Running 4 36 3 27 78 Regan Smith Furniture Row Chevrolet 160 41 77.6 297,345 Running 4 16 1 Jamie McMurray Bass Pro Shops/Tracker Boats Chevrolet 160 41 1 80.5 290,964 Running 1 5 5 9 17 Matt Kenseth Crown Royal Ford 160 40 1 119.1 266,386 Running 2 10 6 24 14 Tony Stewart Mobil 1/Office Depot Chevrolet 160 39 1 85.3 240,508 Running 1 10 7 18 16 Greg Biffle Red Cross Ford 160 37 84.9 201,250 Running 8 12 5 Mark Martin Quaker State/GoDaddy.com Chevrolet 160 36 99.5 189,375 Running 9 5 2 Brad Keselowski Miller Lite Dodge 160 36 1 93.9 204,133 Running 1 17 10 29 18 Kyle Busch M&M's Toyota 160 34 85.7 221,241 Running 11 19 29 Kevin Harvick Jimmy John's Chevrolet 160 33 84.2 214,761 Running 12 23 39 Ryan Newman Haas Automation Chevrolet 160 32 75.2 199,075 Running 13 26 33 Clint Bowyer Cheerios/Hamburger Helper Chevrolet 160 32 1 88.0 197,908 Running 1 2 14 10 99 Carl Edwards Ortho Home Defense Max Ford 160 30 80.6 197,341 Running 15 31 83 Brian Vickers Red -

Nascar Race Hub Honors Women & Crew Chiefs With

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Megan Englehart Monday, August 21, 2017 [email protected] NASCAR RACE HUB HONORS WOMEN & CREW CHIEFS WITH PAIR OF SPECIAL EDITION EPISODES THIS WEEK ON FS1 Specials Feature All-Female “Women in Wheels” Panel on Wednesday and “Crew Chief” Episode on Thursday CHARLOTTE, N.C. – NASCAR RACE HUB, the sport’s most-watched daily news and highlights program, will air two special, one-hour episodes this week honoring the women and crew chiefs in NASCAR. An outgrowth of NASCAR RACE HUB’s regular series with reporter Kaitlyn Vincie titled “Women in Wheels,” Wednesday’s edition of HUB (6:00 PM ET on FS1) will carry the same theme. Co- hosts Shannon Spake, Adam Alexander and Jamie Little welcome to the studio a prestigious panel of females working in NASCAR in various roles. Panelists include JR Motorsports co-owner Kelley Earnhardt Miller, Chevrolet Program Manager Alba Colon, Hendrick Motorsports tire specialist Lisa Smokstad and Hailie Deegan, a member of the NASCAR Next Class and the first female to win a Lucas Oil Off Road Racing Series championship and race. The group will discuss topics such as the state of the sport, ways in which NASCAR continues to develop, the evolution and growth of women in the industry and more. Features on Wednesday’s special include Vincie sit-downs with JTG-Daugherty co-owner Jodi Geschickter, NASCAR SVP and CMO Jill Gregory and tire changer/developmental crew member Brehanna Daniels, as well as a piece exploring Danica Patrick’s impact on young fans. Thursday’s NASCAR RACE HUB edition is co-hosted by Spake and Alexander with FOX NASCAR analysts and former championship-winning crew chiefs Jeff Hammond and Andy Petree. -

General Assembly of North Carolina Session 2001 H 1 House Joint Resolution 270

GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF NORTH CAROLINA SESSION 2001 H 1 HOUSE JOINT RESOLUTION 270 Sponsors: Representatives Johnson, Barnhart; Barbee, Coates, Cox, Goodwin, Hensley, Hilton, Hurley, Luebke, McCombs, and Sexton. Referred to: Rules, Calendar, and Operations of the House. February 27, 2001 1 A JOINT RESOLUTION HONORING THE LIFE AND MEMORY OF DALE 2 EARNHARDT, LEGENDARY STOCK CAR RACER. 3 Whereas, Ralph Dale Earnhardt was born on April 29, 1951, on a farm in 4 Kannapolis, North Carolina; and 5 Whereas, the son of a NASCAR driver Ralph Earnhardt, Dale Earnhardt 6 developed a passion for stock car racing at an early age; and 7 Whereas, Dale Earnhardt began competing in local stock car races as a 8 teenager, eventually competing on the Winston Cup circuit; and 9 Whereas, in 1975, Dale Earnhardt entered his first Winston Cup race at the 10 Charlotte Motor Speedway; and 11 Whereas, in 1979, Dale Earnhardt won his first Winston Cup race at the 12 Bristol Motor Speedway in Bristol, Tennessee, and later that year was named Rookie of 13 the Year; and 14 Whereas, in 1980, Dale Earnhardt clinched the NASCAR Winston Cup 15 championship, making him the first driver to win Rookie of the Year and the Winston 16 Cup championship in successive seasons; and 17 Whereas, in 1984, Dale Earnhardt began driving for Richard Childress, and 18 together they formed a formidable team achieving tremendous success on the racetrack; 19 and 20 Whereas, Dale Earnhardt won NASCAR championships in 1986, 1987, 1990, 21 1991, 1993, and 1994, tying Richard Petty's impressive record -

OFFICIAL RACE REPORT No

NASCAR SPRINT CUP SERIES OFFICIAL RACE REPORT No. 4 52ND ANNUAL FOOD CITY 500 BRISTOL MOTOR SPEEDWAY Bristol, TN - March 18, 2012 .533-Mile Concrete Oval 500 Laps - 266.50 Miles Purse: $5,551,155 TIME OF RACE: 2 hours, 51 minutes, 52 seconds AVERAGE SPEED: 93.037 mph MARGIN OF VICTORY: 0.714 second(s) Fin Str Car Bns Driver Lead Pos Pos No Driver Team Laps Pts Pts Rating Winnings Status Tms Laps 1 5 2 Brad Keselowski Miller Lite Dodge 500 48 5 142.4 $186,770 Running 4 232 2 21 17 Matt Kenseth Best Buy Ford 500 43 1 119.3 179,821 Running 2 45 3 15 56 Martin Truex Jr NAPA Auto Parts Toyota 500 41 104.2 147,149 Running 4 16 15 Clint Bowyer 5-hour Energy Toyota 500 40 107.2 135,124 Running 5 25 55 Brian Vickers Aaron's Toyota 500 40 1 120.5 98,535 Running 3 125 6 33 31 Jeff Burton BB&T Chevrolet 500 38 107.1 139,810 Running 7 17 1 Jamie McMurray McDonald's Chevrolet 500 37 93.1 127,793 Running 8 30 42 Juan Pablo Montoya Target Chevrolet 500 36 84.3 124,351 Running 9 22 48 Jimmie Johnson Lowe's / Kobalt Tools Chevrolet 500 35 94.8 136,596 Running 10 11 27 Paul Menard Menards / MOEN Chevrolet 500 34 88.7 102,060 Running 11 14 29 Kevin Harvick Budweiser Chevrolet 500 33 80.3 139,546 Running 12 3 39 Ryan Newman Quicken Loans Chevrolet 500 32 85.9 132,818 Running 13 1 16 Greg Biffle 811 / 3M Ford 500 32 1 98.7 111,085 Running 1 41 14 23 14 Tony Stewart Office Depot / Mobil 1 Chevrolet 500 30 84.6 140,810 Running 15 18 88 Dale Earnhardt Jr National Guard / Diet Mountain Dew Chevrolet 500 30 1 102.4 100,035 Running 2 2 16 9 20 Joey Logano The Home -

Lead Fin Pos Driver Team Laps Pts Stage 1 Pos Status Tms Laps

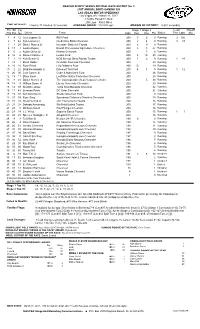

NASCAR XFINITY SERIES OFFICIAL RACE REPORT No. 3 21ST ANNUAL BOYD GAMING 300 LAS VEGAS MOTOR SPEEDWAY Las Vegas, NV - March 11, 2017 1.5-Mile Paved Tri-Oval 200 Laps - 300.0 Miles TIME OF RACE: 2 hours, 31 minutes, 52 seconds AVERAGE SPEED: 118.525 mph MARGIN OF VICTORY: 0.602 second(s) Fin Str Car Stage 1 Stage 2 Lead Playoff Pos Pos No Driver Team Laps Pos Pos Pts Status Tms Laps Pts 1 4 12 Joey Logano (i) REV Ford 200 3 6 0 Running 3 106 2 7 42 Kyle Larson (i) Credit One Bank Chevrolet 200 2 4 0 Running 3 33 3 3 20 Daniel Suarez (i) Interstate Batteries Toyota 200 6 9 0 Running 4 13 7 Justin Allgaier Brandt Professional Agriculture Chevrolet 200 5 3 47 Running 5 5 2 Austin Dillon (i) Rheem Chevrolet 200 7 0 Running 6 16 6 Darrell Wallace Jr Leidos Ford 200 8 10 35 Running 7 1 18 Kyle Busch (i) NOS Energy Drink Rowdy Toyota 200 1 2 0 Running 1 48 8 14 1 Elliott Sadler OneMain Financial Chevrolet 200 29 Running 9 10 16 Ryan Reed Lilly Diabetes Ford 200 10 29 Running 10 2 22 Brad Keselowski (i) Discount Tire Ford 200 4 1 0 Running 1 12 11 20 00 Cole Custer # Code 3 Associates Ford 200 26 Running 12 19 11 Blake Koch LeafFilter Gutter Protection Chevrolet 200 25 Running 13 8 21 Daniel Hemric # The Cosmopolitan of Las Vegas Chevrolet 200 5 30 Running 14 18 9 William Byron # Liberty University Chevrolet 200 23 Running 15 12 33 Brandon Jones Turtle Wax/Menards Chevrolet 200 22 Running 16 11 48 Brennan Poole DC Solar Chevrolet 200 21 Running 17 15 98 Aric Almirola (i) Shelby American Ford 200 0 Running 18 27 39 Ryan Sieg Speedway Children's Charities Chevrolet 200 19 Running 19 22 24 Drew Herring (i) JGL Young Guns Toyota 200 18 Running 20 21 28 Dakoda Armstrong WinField United Toyota 200 17 Running 21 28 5 Michael Annett Pilot Flying J Chevrolet 200 16 Running 22 23 14 J.J. -

Quincy Air Compressors Take the Checkered Flag with Dale Earnhardt Inc

CASE STUDY The Customer: Dale Earnhardt Inc. The Challenge: Race Car Manufacturing The Conclusion: A broad range of Quincy Compressor equipment Quincy Air Compressors Take the Checkered Flag with Dale Earnhardt Inc. Racing Team Dale Earnhardt Inc., The Customer in over 150 countries. Compressor and Patton’s Inc., the By any measure, Dale Earnhardt NASCAR consists of three Quincy distributor in the region, among the winningest Inc. has grown far beyond its major national series – the NASCAR has a bit of legend about it, as well. organizations in humble beginnings. Formed by Sprint Cup Series, NASCAR As Randy Earnhardt, Dale’s Dale and Teresa Earnhardt in Nationwide Series and NASCAR brother and director of purchasing NASCAR racing, relies 1980, Dale Earnhardt Inc. (DEI) Craftsman Truck and inventory had its first “corporate headquar - Series, as well control at DEI, on the rugged reliability ters” in a three-bay garage where as eight regional remembers it, and hard-working Dale had an office. Over the years, series. NASCAR “We were in the need for more space quickly sanctions some need of a com - efficiency of Quincy grew with the addition of more 1,500 races at pressor so we employees and race cars. In 1999, over 100 tracks looked in the air compressors in its DEI opened its new headquarters in 35 states. phone book and demanding manufacturing complete with administration DEI is found Patton’s offices, the Trophy Room, show - composed of was the biggest operations. room and retail store. This main four Sprint Cup name in this complex quickly became a “must teams. -

Official Race Results

NASCAR NATIONWIDE SERIES OFFICIAL RACE REPORT No. 8 21ST ANNUAL AARON'S 312 TALLADEGA SUPERSPEEDWAY Talladega, AL - May 5, 2012 2.66-Mile Paved Tri-Oval 117 Laps - 311.22 Miles Purse: $1,189,238 TIME OF RACE: 2 hours, 22 minutes, 54 seconds AVERAGE SPEED: 136.258 mph MARGIN OF VICTORY: 0.034 second(s) Fin Str Car Bns Driver Lead Pos Pos No Driver Team Laps Pts Pts Rating Winnings Status Tms Laps 1 4 18 Joey Logano (i) GameStop/Max Payne 3 Toyota 122 0 117.9 $42,645 Running 6 17 2 12 54 Kyle Busch (i) Monster Energy Toyota 122 0 125.5 40,100 Running 3 36 3 2 6 Ricky Stenhouse Jr Cargill/Blackwell Angus Ford 122 42 1 92.0 39,193 Running 1 1 4 11 88 Cole Whitt # TaxSlayer.com Chevrolet 122 41 1 100.0 34,318 Running 1 3 5 33 5 Dale Earnhardt Jr(i) Hellmann's Chevrolet 122 0 124.2 23,100 Running 7 25 6 31 1 Kurt Busch (i) HendrickCars.com Chevrolet 122 0 97.8 20,525 Running 1 1 7 7 30 James Buescher (i) Accudoc Chevrolet 122 0 95.8 27,793 Running 2 9 8 13 31 Justin Allgaier Brandt Chevrolet 122 36 85.4 25,143 Running 9 20 99 Kenny Wallace American Ethanol Toyota 122 36 1 93.5 24,918 Running 1 1 10 1 2 Elliott Sadler OneMain Financial Chevrolet 122 35 1 100.0 25,568 Running 3 8 11 18 20 Ryan Truex Grime Boss Toyota 122 34 1 89.5 24,268 Running 1 1 12 8 12 Sam Hornish Jr Alliance Dodge 122 33 1 67.7 24,143 Running 1 2 13 17 7 Danica Patrick GoDaddy.com Chevrolet 122 32 1 90.8 23,968 Running 1 1 14 27 40 Erik Darnell TheMotorsportsGroup.com Chevrolet 122 30 63.2 23,818 Running 15 26 24 John Wes Townley (i) Toyota Save in May Sales Event Toyota -

Elliott Sadler No. 1 Onemain Chevrolet Camaro Chase Elliott No

JR MOTORSPORTS TEAM PREVIEW: TRACK: Talladega Superspeedway RACE: Sparks Energy 300 (113 laps / 300.58 miles) DATE: Saturday, April 30, 2016 Broadcast Information – TV: 3 p.m. ET on FOX / Radio: MRN & Sirius Ch. 90 2:30 p.m. ET “Talladega is a 200-mph chess match, and as fast as we were in Daytona, I know we will have a shot at winning this weekend. I’ve Elliott Sadler always enjoyed plate racing and go into it with a win-or-bring- No. 1 OneMain Chevrolet Camaro the-steering-wheel-back mentality.” – Elliott Sadler In only seven NASCAR Xfinity Series starts at Talladega Superspeedway, Elliott Sadler has one win (2014), two top fives and four top 10s, with one pole. Sadler leads all current full-time NXS drivers in wins at Talladega Superspeedway by way of his 2014 victory. Sadler is currently second in the NXS point standings, only PR Manager: Josh Masten [email protected]; 704-677-6098 nine points back. This season, Sadler has collected three top-five and seven top-10 finishes in eight starts with JR Motorsports. “I’m really looking forward to getting to Talladega with our Breyers Chevy. We’re so close to getting a win for this No. 7 team. I really thought we had a shot at Richmond, but we got caught up in a Justin Allgaier wreck and it just didn’t work out. There are a lot of unknowns at No. 7 Breyers Chevrolet Camaro Talladega, but hopefully we can go out there and finish strong.” – Justin Allgaier Justin Allgaier has three top-10 finishes in his last three NASCAR Xfinity Series starts at Talladega Superspeedway, with a best finish of fifth (2013). -

NASCAR XFINITY Series - Kentucky Speedway - 7/7/2017 Last Update: 7/3/2017 10:06:00 AM

17th Annual Alsco "300" - NASCAR XFINITY Series - Kentucky Speedway - 7/7/2017 Last Update: 7/3/2017 10:06:00 AM Entry Veh # Driver Owner Crew Chief Veh Mfg Sponsor 1 00 Cole Custer Gene Haas Jeff Meendering 17 Ford Haas Automation 2 0 Garrett Smithley Gary Cogswell Wayne Setterington Jr 17 Chevrolet Adapt 2k 3 01 Harrison Rhodes Johnny Davis Tommy MacHek 17 Chevrolet teamjdmotorsports.com 4 1 Elliott Sadler Dale Earnhardt Jr Kevin Meendering 17 Chevrolet OneMain Financial 5 2 Paul Menard(i) Richard Childress Randall Burnett 17 Chevrolet Richmond/Menards 6 3 Ty Dillon(i) Richard Childress Matt Swiderski 17 Chevrolet Rheem 7 4 Ross Chastain Gary Keller Evan Snider 17 Chevrolet teamjdmotorsports.com 8 5 Michael Annett Dale Earnhardt Jr Jason Stockert 17 Chevrolet Pilot Flying J 9 07 Ray Black II Bobby Dotter Jason Miller 17 Chevrolet TBD 10 7 Justin Allgaier Kelley Earnhardt-Miller Jason Burdett 17 Chevrolet Hellmann's 11 8 BJ McLeod Jessica Smith-McLeod David Ingram Jr 16 Chevrolet TBD 12 9 William Byron Rick Hendrick David Elenz 17 Chevrolet AXALTA / Mansea Metal 13 11 Blake Koch Matt Kaulig Chris Rice 17 Chevrolet LeafFilter Gutter Protection 14 12 Ryan Blaney(i) Roger Penske Brian Wilson 17 Ford Snap-On 15 13 Timmy Hill Danielle Long Jason Houghtaling 17 Toyota TBD 16 14 JJ Yeley Mark Smith Wally Rogers 17 Toyota TriStar Motorsports 17 15 Joe Nemechek(i) Carol Clark TBA 17 Chevrolet teamjdmotorsports.com 18 16 Ryan Reed Jack Roush Phil Gould 17 Ford Lilly Diabetes 19 18 Kyle Busch(i) J D Gibbs Eric Phillips 17 Toyota NOS Energy Drink -

Board of Education Approves Fiscal Year 2014 Budget

A1 Special section inside HOW-TO GUIDE A SPECIAL SUPPLEMENT TO THE NORTHEAST GEORGIAN • SUMMER 2013 The Northeast Georgian 75 cents JUNE 28, 2013 Weekend Board of education approves Fiscal Year 2014 budget By KIMBERLY BROWN the projected 2014 ending “everybody in the school yond our control, but we “That’s made up of [in- “They were not discretion- fund balance of $2,974,496 system” for their work are optimistic that our creased pay for] advanced ary in any way.” The Habersham Coun- balances the budget at $61 on the budget. “We have economy is going to come degrees, health insurance “We’ve had savings ty Board of Education million. closed our gap between back,” Newsome said. increases for both clas- through attrition, absorb- has approved a balanced The budget was pre- our revenue and expen- “We’re going to have more sifi ed and certifi ed staff, ing positions, we’ve had general fund budget for sented June 27 by school ditures,” she said. “It is businesses, so we feel like also our teacher retire- savings through the zero- fi scal year 2014 of about system Chief Financial Of- much less. It is still there; everything on that side ment expenditures are based budget process, and $61 million. That budget fi cer Staci Newsome, who there’s still a gap, but (revenue) is mostly posi- going up,” Newsome said. of course the conservative includes projected rev- said the budget was the we’re on the way.” tive.” “Our expenditures auto- spending,” Newsome said. enues of $56,337,923, with same which had been ap- Newsome said the coun- Habersham County matically went up, beyond “We’ve also been able to a current 2013 fund bal- proved as a tentative bud- ty tax digest should be re- School Superintendent our control, by that much shift over some of our pur- ance of $4,879,614. -

Media Notebook

DRIVER: Kasey Kahne / No. 88 Great Clips Chevrolet RACE: Furious 7 300 (200 laps / 300 miles) TRACK: Chicagoland Speedway DATE: Saturday, Sept. 19, 2015 Quotes | Kasey Kahne “Chicago has always been a fun track for me and I’m ready to get back in the MEDIA INFORMATION TV: NBCSN (6 p.m. ET) No. 88 Great Clips car. We had a good race there last year and came home in RADIO: MRN and Sirius XM Ch 90 (6 p.m. ET) fourth. JR Motorsports had a great weekend in Richmond and I’m looking forward to continuing that at Chicagoland.” FINAL PRACTICE: 9/18, 2-4:25 p.m. ET (NBCSN) QUALIFYING: 9/19, 2:45 p.m. ET (NBCSN) GREEN FLAG: 9/19, 6 p.m. ET (NBCSN) Notes | No. 88 Team 2015 XFINITY SERIES OWNER POINTS KAHNE IN THE WINDY CITY: Kahne is making his ninth career NASCAR XFINITY 1. Roger Penske (#22) .........................................999 Series (NXS) start at Chicagoland Speedway this weekend. The NASCAR Sprint 2. JD Gibbs (#54) ................................................... -82 Cup Series veteran has earned two top-five and two top-10 finishes at the 1.5- 3. Jack Roush (#60) .............................................. -91 mile speedway. Kahne made his first Chicagoland NXS start for JRM last year. 4. Dale Earnhardt Jr. (#9)........................ -112 He had a stout run in the 200-lap event, tying his personal best Chicagoland NXS finish of fourth. 5. Richard Childress (#3)................................. -118 6. Richard Childress (#33) .............................. -120 KAHNE’S SEASON RECAP: This year, Kahne has three top-five and three-top 10 7. Kelley Earnhardt-Miller (#7) ..............