Covid-19 on Twitter: an Analysis of Risk Communication with Visuals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

アーティスト 商品名 品番 ジャンル名 定価 URL 100% (Korea) RE

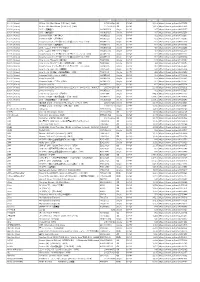

アーティスト 商品名 品番 ジャンル名 定価 URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 K-POP 2,290 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 K-POP 2,290 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 K-POP 1,296 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 K-POP 1,296 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 K-POP 648 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 K-POP 648 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 100% (Korea) How to cry (ミヌ盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5005 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415958 100% (Korea) How to cry (ロクヒョン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5006 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415970 100% (Korea) How to cry (ジョンファン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5007 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415972 100% (Korea) How to cry (チャンヨン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5008 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415974 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you (A) OKCK5011 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655024 100% (Korea) Song for you (B) OKCK5012 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655026 100% (Korea) Song for you (C) OKCK5013 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655027 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) -

Fenomén K-Pop a Jeho Sociokulturní Kontexty Phenomenon K-Pop and Its

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI PEDAGOGICKÁ FAKULTA Katedra hudební výchovy Fenomén k-pop a jeho sociokulturní kontexty Phenomenon k-pop and its socio-cultural contexts Diplomová práce Autorka práce: Bc. Eliška Hlubinková Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Filip Krejčí, Ph.D. Olomouc 2020 Poděkování Upřímně děkuji vedoucímu práce Mgr. Filipu Krejčímu, Ph.D., za jeho odborné vedení při vypracovávání této diplomové práce. Dále si cením pomoci studentů Katedry asijských studií univerzity Palackého a členů české k-pop komunity, kteří mi pomohli se zpracováním tohoto tématu. Děkuji jim za jejich profesionální přístup, rady a celkovou pomoc s tímto tématem. Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně s použitím uvedené literatury a dalších informačních zdrojů. V Olomouci dne Podpis Anotace Práce se zabývá hudebním žánrem k-pop, historií jeho vzniku, umělci, jejich rozvojem, a celkovým vlivem žánru na společnost. Snaží se přiblížit tento styl, který obsahuje řadu hudebních, tanečních a kulturních směrů, široké veřejnosti. Mimo samotnou podobu a historii k-popu se práce věnuje i temným stránkám tohoto fenoménu. V závislosti na dostupnosti literárních a internetových zdrojů zpracovává historii žánru od jeho vzniku až do roku 2020, spolu s tvorbou a úspěchy jihokorejských umělců. Součástí práce je i zpracování dvou dotazníků. Jeden zpracovává názor české veřejnosti na k-pop, druhý byl mířený na českou k-pop komunitu a její myšlenky ohledně tohoto žánru. Abstract This master´s thesis is describing music genre k-pop, its history, artists and their own evolution, and impact of the genre on society. It is also trying to introduce this genre, full of diverse music, dance and culture movements, to the public. -

URL 100% (Korea)

アーティスト 商品名 オーダー品番 フォーマッ ジャンル名 定価(税抜) URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤C> OKCK5022 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732096 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤B> OKCK5021 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732095 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (チャンヨン)(LTD) OKCK5017 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655033 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤A> OKCK5020 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732093 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ジョンファン)(LTD) OKCK5016 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655032 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ヒョクジン)(LTD) OKCK5018 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655034 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 Single K-POP 421 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 -

Trans)Gender Ontologies for South Korean Namjangyeoja Television Dramas

SHOULD WE PASS ON “PASSING WOMEN”?: THE STAKES OF (TRANS)GENDER ONTOLOGIES FOR SOUTH KOREAN NAMJANGYEOJA TELEVISION DRAMAS BY SHELBY STRONG THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in East Asian Studies in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2018 Urbana, Illinois Adviser: Professor Jeffrey T. Martin ABSTRACT Scholarship has gendered the protagonists of namjangyeoja dramas, South Korean live- action television dramas that focus on the lives of female-assigned people who pass as men, as “women”. I argue that we must push back against this narrow reading of namjang characters and instead embrace ambiguity and plural possibilities in namjang gender representations. The widespread pattern of namjang characters being depicted as being coerced into “confessing” that they are “women” calls into question the idea that their “real” gender can only be read as female, static, and singular. Indeed, a deeper reading reveals how some namjang protagonists are portrayed as identifying as gender non-binary and gender fluid. I propose that using “transgender” and “namjangyeoja” in conjunction with each other can help us orient to transgender possibilities in namjang dramas and illuminate how the pervasive practice of using “namjangyeoja” to categorize performances of gender nonconformity by female-assigned people is imbricated with institutionalized forms of transphobic heteronormative familism in South Korea. Ultimately, I argue that we must be vigilant about how our choice to affirm certain ontologies (e.g., “namjangyeoja”) over others (e.g., “transgender”) enacts epistemological forms of violence that support larger, institutionalized projects of death by exclusion and illegibility. -

DOWNLOAD APLIKASINYA GRATIS Premieres Tuesday, August 9

t MY TOP 10 ARIA THE SCARLET AMMO DOUBLE A MY TOP ANIMAX Seorang gadis muda mengidolakan dan mempunyai mimpi untuk mengikuti jejak dari idolanya yang merupakan seorang S-ranked butei yang bernama Kanzaki H. Aria. Tetapi, karena ia tidak terlalu pandai, ia hanya 10FAVORITE PROGRAMS mendapatkan ranking E saja! PJ MASKS VERTICAL LIMIT DISNEY JUNIOR FOX ACTION MOVIES Film ini berkisah sebuah film yang mengisahkan tentang perjalanan tim pendaki gunung, yang Serial animasi ini berkisah tentang anak-anak mencoba menaklukkan berumur 6 tahun yang hidup relatif normal di siang gunung paling ganas. hari. Mereka bertetangga, teman sekelas, dan teman Film ini dibintangi lainnya. Pada malam hari, mereka mengaktifkan Chris O’Donnel, Robin gelang mereka dan mengubah mereka menjadi Tunney, Stuart Wilson identitas lain, yaitu PJ Masks. dan Bill Paxton. A MIGHTY HEART OUTCAST HBO SIGNATURE FOX Film ini berpusat Outcast pada kisah merupakan serial pencarian wartawan komik pertama Wall Street Journal, yang ditulis oleh Daniel Pearl yang Kirkman, bercerIta diculik di Karachi, tentang karakter Pakistan oleh bernama Kyle Omar Sheikh pada Barnes yang tahun 2002. Film mempunyai ini menceritakan masalah dengan perjuangan Departemen Kehakiman dan setan sejak kecil. pemerintah Amerika Serikat yang berjuang untuk Dengan bantuan melacak para penculik dan membawa mereka ahli mistis dia berusaha membongkar apa yang ke pengadilan. dibalik semua kejadian yang menimpanya. 4 t MY TOP 10 DARK MATTER THE CHOSEN ONE: SYFY CHARLIE PUTH CHANNEL V “The Chosen One: Charlie Puth” menceritakan tentang perjalanan Serial ini dimulai dengan kisah 6 orang musik seorang yang mendadak terbangun dari kapsul tidur penyanyi panjangnya di dalam pesawat antariksa, dan muda Charlie semuanya mengalami hilangnya sebagian Puth pada besar ingatan dan kenangan penting mereka. -

Universidade Federal Do Ceará Instituto De Cultura E Arte Curso De Design-Moda

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO CEARÁ INSTITUTO DE CULTURA E ARTE CURSO DE DESIGN-MODA RAFAELA PRADO DO AMARAL KPOP: PADRÃO DE BELEZA, MÍDIA E SUAS IMPLICAÇÕES NO COTIDIANO DOS GRUPOS FEMININOS NA COREIA DO SUL FORTALEZA 2019 RAFAELA PRADO DO AMARAL KPOP: PADRÃO DE BELEZA, MÍDIA E SUAS IMPLICAÇÕES NO COTIDIANO DOS GRUPOS FEMININOS NA COREIA DO SUL Monografia para o trabalho de conclusão de curso, em Design-Moda da Universidade Federal do Ceará, como requisito para obtenção do título de graduado. Orientadora: Profª. Drª. Francisca Raimunda Nogueira Mendes FORTALEZA 2019 Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação Universidade Federal do Ceará Biblioteca Universitária Gerada automaticamente pelo módulo Catalog, mediante aos dados fornecidos pelo(a) autor(a) A517k Amaral, Rafaela Prado do. Kpop: padrão de beleza, mídia e suas implicações no cotidiano dos grupos femininos na Coreia do Sul / Rafaela Prado do Amaral. – 2019. 61 f. : il. color. Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso (graduação) – Universidade Federal do Ceará, Instituto de cultura e Arte, Curso de Design de Moda, Fortaleza, 2019. Orientação: Profa. Dra. Francisca Raimunda Nogueira Mendes . 1. Kpop. 2. Corpo. 3. Mídia. 4. Padrão de beleza. I. Título. CDD 391 RAFAELA PRADO DO AMARAL KPOP: PADRÃO DE BELEZA, MÍDIA E SUAS IMPLICAÇÕES NO COTIDIANO DOS GRUPOS FEMININOS NA COREIA DO SUL Monografia para o trabalho de conclusão de curso, em Design-Moda da Universidade Federal do Ceará, como requisito para obtenção do título de graduado. Aprovada em: ___/___/______. BANCA EXAMINADORA ________________________________________ Profª. Drª. Francisca Raimunda Nogueira Mendes (Orientadora) Universidade Federal do Ceará (UFC) _________________________________________ Profª. Drª. Cyntia Tavares Marques de Queiroz Universidade Federal do Ceará (UFC) _________________________________________ Profª. -

Show, Don't Tell

SHOW, DON’T TELL A Reflection on Korean Popular Music Videos MA THESIS FILM STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF AMSTERDAM Author: Eva Heijne Student no.: 11774592 Date of completion: June 20, 2018 Supervisor: Dr. Gerwin van der Pol Second Reader: Dr. Erik Laeven Heijne 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1: K-pop: Between a Rock and a Hard Place? .................................................................................. 5 1.1 TRAGEDY STRIKES: THE SEWOL FERRY DISASTER, LADIES’ CODE AND JONGHYUN ............................................. 5 1.2 SOUTH KOREA AND K-POP: THE INDUSTRY AND ITS POPULARITY ...................................................................... 7 1.3 SEX, DRUGS AND K-POP: SCANDAL AND SOUTH KOREAN SOCIETY ................................................................ 10 1.4 THE CURRENT STATE OF K-POP AND HALLYU .................................................................................................... 11 1.5 CONCLUSION ............................................................................................................................................................. 14 Chapter 2: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly: the K-pop cultural industry ....................................... 15 2.1 HOLLYWOOD AND KOREA: CENSORSHIP AND AUTHORSHIP ............................................................................. 16 2.2 CONTENT VERSUS -

Fiestar One More 1080I Vs 1080Pl

Fiestar One More 1080i Vs 1080pl Fiestar One More 1080i Vs 1080pl 1 / 3 2 / 3 See more of Sharing Korea Torrent on Facebook. Log In ... [Mnet] M Countdown E655 200305 (Full Show 720p & 1080i) ... IZ*ONE, (G)I-DLE (MIYEON, MINNIE), LOONA, YEZI (Ex-FIESTAR), ... The Winner is : IZ*ONE ... [Notice] : English Subtitle for 720p -NEXT not sync starts at 00:30:14 and normal sync for 1080p -NEXT.. Dark Horse Katy Perry 1080p Backgrounds - http://bit.ly/2o9ho93 ... fiestar one more 1080p vs 720p video full hd 1080p ... trilogia o grande mestre 720p vs 1080i. BIGBANG & 2NE1 - Lollipop (Mnet Japan-1080i).ts. Blady - Blood ... Cats - Handsome Boy (Channel V).tp ... CSJH The Grace - One More Chance (GomTv 1080p).mp4 ... FIESTAR - You're Pitiful (2015 Melon 1080p).mp4. 1080i 1080p 2ne1 4minute 60fps after school aoa apink bestie blackpink bts ... dreamcatcher elris exid exo f(x) fiestar gfriend girl'sday gugudan hello venus hyorin ... They also reached number one on the weekly, popularity, music video, and ... AS IF IT'S YOUR LAST -Music Video-6. blackpink《playing with fire》mv播放量破 .... So after watching Girl's Day - Darling in 60fps from this thread and reading all the ... AOA - Short Hair (Eye Contact Ver) Streamable .webm & (Mirror for 1080 DL) ... But I do think it's possible to get it 1080p youtube ripped and keep it 1080p (like my FIESTAR and the Red Velvet one), ... More posts from the kpop community.. 车展模特-2014武汉车展V领黑色礼服模特魅力十足. 高清. 01:10. 车展模特-2014武汉 ... FIESTAR - One More (Making) (HD-1080p). 超清. 04:25. FIESTAR - One .... Captain Marvel vs Thanos Avengers Endgame HD 1080P 60FPS. -

Universidade De Brasília Centro De Excelência Em Turismo Rayssa Dos Santos De Moura O Soft Power Da Música Como Atrativo

UNIVERSIDADE DE BRASÍLIA CENTRO DE EXCELÊNCIA EM TURISMO RAYSSA DOS SANTOS DE MOURA O SOFT POWER DA MÚSICA COMO ATRATIVO TURÍSTICO: UMA ANÁLISE DA ONDA HALLYU BRASÍLIA – DF 2021 UNIVERSIDADE DE BRASÍLIA CENTRO DE EXCELÊNCIA EM TURISMO RAYSSA DOS SANTOS DE MOURA O SOFT POWER DA MÚSICA COMO ATRATIVO TURÍSTICO: UMA ANÁLISE DA ONDA HALLYU Monografia apresentada ao Centro de Excelência em Turismo da Universidade de Brasília (UnB), como requisito para obtenção do título de Bacharel em Turismo. Orientadora: Prof.ª M.ª Lívia Cristina Barros da Silva Wiesinieski BRASÍLIA – DF 2021 O SOFT POWER DA MÚSICA COMO ATRATIVO TURÍSTICO: UMA ANÁLISE DA ONDA HALLYU RAYSSA DOS SANTOS DE MOURA BANCA EXAMINADORA __________________________________________________ Orientadora: Prof.ª M.ª Lívia Cristina Barros da Silva Wiesinieski Centro de Excelência em Turismo (CET/UnB) __________________________________________________ Prof.ª M.ª Aylana Laíssa Medeiros Borges Centro de Excelência em Turismo (CET/UnB) __________________________________________________ Prof.ª M.ª Alessandra Santos dos Santos Centro de Excelência em Turismo (CET/UnB) __________________________________________________ Prof.ª Dr.ª Gabriela Zamignan de Andrade Mello - Suplente Centro de Excelência em Turismo (CET/UnB) BRASÍLIA – DF 2021 AGRADECIMENTOS Agradeço a Deus por me guiar nesse caminho. Agradeço as três pessoas mais importantes da minha vida, as minhas maiores inspirações, suporte e apoio em toda essa trajetória, que são minha mãe e minhas irmãs, Arlete, Rebeca e Raquel. Aos meus familiares que me apoiaram e torceram por mim: meu pai Júnior, minhas tias Neide e Sandra, minhas primas Jessika, Júlia e Maria Eduarda, minhas avós Carmélia e Clemides e meus falecidos avôs Nilo e Raimundo. -

A Cultura Do K-Pop: Uma Investigação Sociocultural

2020 ANA FILIPA A CULTURA DO K-POP: AUGUSTO FLOR UMA INVESTIGAÇÃO SOCIOCULTURAL DA COREIA DO SUL, DA SUA INDÚSTRIA MUSICAL E DOS PRODUTOS AUDIOVISUAIS DO GRUPO BTS ENTRE 2013-2020 2020 - 02 - 07 EV00; 195.IAD - MOD MOD-195.IADEV00; 07-02-2020 2020 ANA FILIPA A CULTURA DO K-POP: AUGUSTO FLOR UMA INVESTIGAÇÃO SOCIOCULTURAL DA COREIA DO SUL, DA SUA INDÚSTRIA MUSICAL E DOS PRODUTOS AUDIOVISUAIS DO GRUPO BTS ENTRE 2013-2020 Dissertação apresentada ao IADE - Faculdade de Design, Tecnologia e Comunicação da Universidade Europeia, para cumprimento dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do grau de Mestre em Design e Cultura Visual, realizada sob a orientação científica do Doutor Flávio Almeida, Professor Auxiliar da Universidade da Beira Interior. 2020 - 02 - 07 EV00; 195.IAD - MOD MOD-195.IADEV00; 07-02-2020 Dedico este trabalho às sete almas que inspiraram esta investigação e que me apresentaram um novo mundo cheio de arte, criatividade, trabalho e dedicação. Às sete almas que me inspiraram a seguir os meus sonhos e a nunca desistir dos meus objetivos. Às sete almas que estão comigo nos bons e maus momentos. Às sete almas que são a razão para esta investigação existir. 2020 - 02 - 07 EV00; 195.IAD - MOD MOD-195.IADEV00; 07-02-2020 Começo por agradecer à minha família que sempre me encorajou agradecimentos a continuar os meus estudos, a seguir os meus sonhos e que me proporcionou a oportunidade de realizar esta investigação. Ao Yuri San por estar sempre ao meu lado, nos bons e maus momentos. Ao meu orientador Flávio Almeida, por toda a ajuda, tempo e dedicação que disponibilizou ao longo desta jornada.