A Textile Workshop from Roman Times: the Villa Dels Antigons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Special and Unusual Loom Frame from the First Half of the Nine

FINDING THE THREAD RESTORATION OF A PROFESSIONAL WEAVER'S LOOM Rabbit Goody A special and unusual loom frame from the first half of the nine teenth century now in the collection of the Ontario Agricultural Mu seum, Milton, Ontario,1 has provided an opportunity to examine some of the specialized equipment used by weavers in the nineteenth century to weave cloth with speed, intricate geometric patterns, and/or accommodate longer lengths of cloth. Surviving examples of cloth have made it apparent that trained weavers, weaving fancy cloth during the nineteenth century were using more complex equipment than that commonly associated with home textile produc tion. However, until now surviving examples of the equipment have been scarce. The museum's loom is one of a small number that can be linked to the production of the more complex cloths of this pe riod. At least, it has specialized equipment which professional weavers might choose to place on their looms. It is the most com plete example currently known. In their book, "Keep Me Warm One Night", Dorothy and Harold Burnham have identified this loom as being a professional weaver's loom because of its specialized features.2 It is being restored for the purpose of reproducing some of the more intricate cloth woven by professional weavers in the Niagara Peninsula. The survival of this loom frame, with its special features, has made it possible to set certain criteria for identifying other looms used by professionals and to corroborate the descrip tions of equipment and methods found in publications and manuscripts from the last half of the eighteenth century and early nineteenth century used to weave fancy cloth rapidly by profes sionals. -

NEEDLEWORK / FIBER Introduction to Inkle Weaving

Inkle and Tablet Weaving Next Steps – Beyond the Basics A lecture and discussion class covering inkle and tablet (card) weaving techniques that go beyond warp based designs. Class will cover: Patterning using brocading and pickup work; adding beads, loops, bells, and fringe; adding and removing warp threads; using multiple shuttles. There are no hands on activity in the class; we’ll have descriptive handouts, samples, demos, and discussion. I. Who am I: Mistress Lynnette de Sandoval del Valle de los Unicornios … [email protected] II. Who are you? A. Lots of Inkle? B. Other weaving? C. Bring anything to share? III. Art vs. Functionality A. What does that mean? B. Who cares? C. Is inkle weaving Period? 1. The looms we use – no 2. Warp faced weaving – yes! D. What do you expect in the way of wear and tear IV. Adding stuff to the Warp and Weft threads A. Adding sticks / feathers / etc 1. Lay in while weaving 2. Sticks wider than loom 3. Should you glue at edge ???? 4. Christmas Tree 5. Spacing: Count Warp threads / measure B. Measure: Pre-measured / knotted non-stretch cord 1. Weaving Multiple, measured strips in one warping C. Concept: Secondary Weft 1. What is it? a) Additional Weft thread(s) 2. Why? a) Main Weft holds the weaving together b) Secondary Weft adds style elements 3. Disadvantages a) Adds thickness to rows 1) Use thinner / softer yarn if possible 2) Beat down harder b) Shows at salvages 1) Use same or complementary color if possible 2) Monofilament thread / fish line @Debbie Coyle (Unicorn Fiber Arts) & Angela of Rosebury p. -

Glossary of Tapestry Terms

[This glossary is not meant to be all-inclusive, or the ultimate authority on definitions. It was developed from a few submitted glossaries and includes primarily words that refer directly to tapestry weaving. However, the glossary is meant to be useful. So with that objective, we would like to experiment with a “Wikipedia” style glossary. You can: • add a word and its definition. • add to, or modify the definition of one of the words already in the glossary. • submit a digital image to illustrate one of the terms. Submit your additions to: Mary Lane: [email protected] Thanks for helping out!] Glossary of Tapestry Terms Abrash – Slight variations in the weft color due to different dye lots, or to differences in dye absorption in the same dye lot. Arrondiment – (French) Soumak. Aubusson – (French) A city in France in which many commercial, low warp ateliers are located. The word is often used to refer, in a generic way, to low warp weaving. Awl – A pointed, metal instrument used for piercing small holes in leather, wood, etc. Weavers use awls to loosen, or pick apart, the densely packed weft and to manipulate the surface of the woven fabric. Basse-licier – (French) Low warp tapestry weaver. Basse lisse – (French) A low warp loom; low warp weaving. Bâton de croisure – (French) Shed stick. Battage – (French) A woven technique used for shading and transparencies in which the number of full passes of two or more colors changes in a proportional manner. Beams – Rollers on a loom, the warp beam holds the extra warp and the cloth beam holds the finished cloth. -

Dark Age Tablet Weaving

Dark Age Tablet Weaving for Viking and Anglo-Saxon re-enactors 1 Introduction Tablet weaving, also known as card weaving, is a method of using square tablets with holes in the corners to weave narrow decorative bands made of wool, linen or silk threads. Tablet weaving was widespread in Europe and Britain in the first millenium AD and is an excellent craft for historical re-enactors as it is portable, interesting, little known nowadays and you can make beautiful bands to decorate your outfit. However, creating replicas of Dark Age bands is challenging. Many of the surviving historic bands are difficult to weave, and so most re-enactors either buy in tablet-weaving or weave simplified bands, and may use patterns and techniques that aren't appropriate to the Dark Ages. The aim of this document is to describe the characteristic styles and methods of Dark Age tablet- weaving. There is also information about materials, equipment and tablet-weaving techniques. Perhaps the most striking theme of the historic bands is inventiveness, and the advantage of the historic techniques is that they allow the weaver to create a far wider range of patterns than the modern methods, which were mostly developed in the 19th and 20th centuries as tablet-weaving was 'rediscovered' in Europe1. This document isn't exhaustive, and I recommend that the interested reader explore further patterns and techniques. There are many good patterns available online. Just remember, as I once read on the internet, the first instruction in tablet weaving is “remove the cat”. Please contact me with any comments or corrections. -

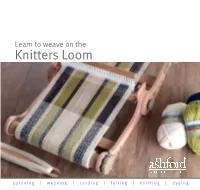

Learn to Weave on the Knitters Loom

Learn to weave on the Knitters Loom spinning | weaving | carding | felting | knitting | dyeing Welcome to the wonderful world of weaving ... YOUR FIRST PROJECT – A SCARF You will need: Warp A pair of sharp scissors Use Ashford Tekapo in stripes of white, blue, yellow and green. A measuring tape Length – 2m (78ins) allowing 15cm (6ins) at each end for fringe Cardboard warp sticks Number of ends – 88 One long table or two smaller tables Finished width – 26cm (10¼ins) Yarn Weft For this project we have used Ashford Tekapo, a smooth Ashford Tekapo #206 Natural White. DK (double knit) sport weight yarn with a slightly textured handspun look, for the warp and the weft. Ashford Tekapo 8ply/DK yarn (100% wool, 200m/218yds, 100gm net) #206 Natural White, #230 Midnight Blue, #203 Butter, #221 Chartreuse. WARP AND WEFT These are two terms you will need to know as they form the basis of all weaving. The warp threads are put onto the loom first. They are held on the loom under tension between the front and back roller. The weft threads pass over and under the warp threads to form the woven fabric. warp weft SHED The shed is the opening formed in the warp, through which the shuttle passes. OPTIONAL ACCESSORIES Extra reeds 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 and 60 dents per 10cm (2.5, 5, 7.5, 10, 12.5 and 15 dents per inch), vari dent reed, loom stand, pickup sticks, shuttles, weaving needles, tapestry beater, warp thread weights, fringe twister. Knitters loom 30cm (12"), carry bag included, loom stand optional back roller warp stick ties handle cog pawl shuttles warp reed support block sticks clamps reed warping threading hook peg base cardboard warp sticks front roller warping peg THE LOOM The reed has large holes and slots to accommodate a larger The shuttle is used to carry the weft yarn from side to side to variety of yarns. -

Learn to Weave on the Table Loom Welcome to the Wonderful World of Weaving

Learn to weave on the Table Loom Welcome to the wonderful world of weaving ... Welcome to the wonderful world of weaving. You are starting an exciting journey of discovery and we know you will enjoy all the texture and colour, creativity and satisfaction that weaving will bring. We make a range of table looms. The four and eight shaft looms are available 40, 60 or 80cm (16, 24 or 32in) wide. There is also a 16 shaft table loom 60cm (24in) wide. This booklet shows our easy warping method and gives instructions for a first project. We used a 40cm (16in) table loom but the instructions apply to all our table looms. Happy weaving. Four Shaft 60cm (24in) pictured with optional stand Elizabeth and Richard Ashford and treadle kit Eight Shaft 40cm (16in) Sixteen Shaft 60cm (24in) pictured with optional stand and weft around a ruler or yarn gauge for Glossary one inch (25mm). The number of times the warp yarn wraps around the ruler is the correct sett. Before you begin your first project on the table loom, here is a Shafts(Harnesses) Frames which hold the heddles. Shaft one glossary of weaving terms you will need to know to get started. is the shaft closest (front) to the weaver. Shed Opening formed in the warp to allow the Beaming Winding the warp under tension onto the shuttle to pass. back roller. Shuttle Holds the weft yarn. Beater Frame holding the reed. Beats the weft Sleying Threading the warp ends through the thread into place. reed. Cross Sticks Sticks used to keep the warp threads in Threading Cross Made while winding the warp. -

The Textile Terminology in Ancient Japan

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Centre for Textile Research Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD 2017 The exT tile Terminology in Ancient Japan Mari Omura Gangoji Institute for Research of Cultural Property Naoko Kizawa Gangoji Institute for Research of Cultural Property Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/texterm Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, Classical Literature and Philology Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Indo-European Linguistics and Philology Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, Museum Studies Commons, Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons, and the Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Omura, Mari and Kizawa, Naoko, "The exT tile Terminology in Ancient Japan" (2017). Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD. 28. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/texterm/28 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Centre for Textile Research at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The Textile Terminology in Ancient Japan Mari Omura, Gangoji Institute for Research of Cultural Property Naoko Kizawa, Gangoji Institute for Research of Cultural Property In Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD, ed. Salvatore Gaspa, Cécile Michel, & Marie-Louise Nosch (Lincoln, NE: Zea Books, 2017), pp. -

Making a Natural Weaving Keywords

Making a Natural Weaving Keywords: • Loom - a frame (or machine) upon which weaving is done. • Warp - vertical threads that form the base of a weaving. To "warp" means to string thread onto a loom. • Weft - the horizontal threads that are woven across the warp. Branches or grasses woven horizontally are also weft. • Heddle - structure used to guide warp threads in a loom. • Selvedge (selvage) - the edge on either side of a woven fabric so finished as to prevent unraveling. • Beat in - to push the new row of weft against the previously woven row. • Beater (shed stick) - stick, fork or comb used to tightly pack the weft threads. • Shed - a space created between the warp threads and those lifted by the shed stick. In these spaces, we can weave grasses, branches or string. List of Materials: • Two branches which will make up the top and bottom of weaving, roughly 6 inches long • Warp - 32 yards of strong, thin thread in neutral color • Weft - a variety of materials gathered from nature: twigs, grasses, pine straw, pods or seed heads with stems attached, feathers, Spanish moss, shells, small pine cones, beads, yarn or thread • A ruler to be used as a shed stick • Belt or ribbon to fasten warp to waist • C-clamp or fixed object to tie end of warp 1 ©2016 ETV Commission A Natural State on Knowitall.org to a countertop, table leg or chair • Scissors • Masking tape • Table leg, chair or other sturdy, fixed object • 11 craft sticks (you may substitute popsicle sticks or tongue depressors, or have any variation of these- as long as they have equal length) • Small drill • Wood glue or strong white glue Directions To Construct a Heddle: 1) Gather your 11 tongue depressors, craft sticks, or popsicle sticks. -

Toika Catalogue 2008

HAND LOOMS & WEAVING EQUIPMENT TOIKA KY P.O. Box 25 37801 TOIJALA FINLAND www.toika.com CONTENTS Floor looms 3 Computer looms 6 Small looms 8 TOIKA is a family business, founded in 1898. For several Supplementary equipment 10 decades it has been one of the leading manufacturers Loom reeds 13 of weaving equipment in the world. The fourth generation Bobbin winders 14 is now leading its operations. Stretchers 15 Shuttles 16 Experience and continuity are the values which we consider Warping equipment 17 important in the manufacture of our weaving equipment. Cords & heddles 19 We think that every item should be both functional and Other equipment 20 esthetically pleasing. The high quality of TOIKA looms is Yarns 21 recognized all over the world. Equipment for bobbin lace 23 All TOIKA looms are made of high quality, selected Finnish birch, which has been both air-dried and kiln-dried. Parts subject to bending are laminated for extra strength. A distinguishing feature of TOIKA looms is the use of a special TOIKA KY varnish in the finishing process which preserves the original P.O. Box 25, Haittilantie 4 A light colour of the hardwood. 37801 TOIJALA FINLAND All TOIKA looms are guaranteed for 2 years against defects Tel. +358 (0)3 542 1095 in material and workmanship. Fax +358 (0)3 542 1001 Email: [email protected] www.toika.com EEVA (4322-4398) F L The Eeva loom is a large traditional Scandinavian loom for weaving all kinds of projects from O light transparent fabrics to heavy rugs. Eeva O usually is equipped with a hanging beater, but an underslung can be ordered. -

Study of Reed on High Speed Weaving Machines

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056 Volume: 06 Issue: 10 | Oct 2019 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072 Study of Reed on High Speed Weaving Machines Prof. A.N. Purant1, Mr. D.R. Bamb2, Mr. Rakesh Dugge3 1Assistant Professor in D.K.T.E.’s Textile & Engineering Institute, Ichalkaranji 2General Manager Schoch Reeds India Pvt. Ltd. Gadmudashingi, Kolhapur 3 Research Scholar D.K.T.E.’s Textile & Engineering Institute, Ichalkaranji ----------------------------------------------------------------------***--------------------------------------------------------------------- Abstract - This paper is focused on the life of the reed. Life 1.1 Reed of reed is decreasing because of Groove's formation of reed on a high-speed weaving machine. Groove formation of the reed is one of the disturbing elements in decreasing weaving performance and life of the reed. It happens at an early stage of running (Approx 500 Hrs). The main objective of this paper is to know how to increase the life of reed on the high-speed weaving machine. These factors are the construction of Fabric, Type of Yarn, Loom Settings, Sizing recipe, Reed Construction A: wires or dents plays an important role to reduce the life of the reed. The life B: wooden ribs of reed needs to be increased because of its cost and C: tarred cord productivity of looms. A reed is part of a weaving loom and resembles a comb. It is Key Words: Life of reed, Groove formation, Weaving used to separate and space the warp threads, to guide performance, High speed weaving machine, cost and the shuttle's motion across the loom, and to push productivity. -

Full Price List

AVL Looms Price List Effective July 2021 AVL Looms, Inc 2360 Park Avenue Chico, CA 95928 530-893-4915 (phone) 800-626-9615 (toll free) 530-893-1372 (fax) [email protected] www.avlusa.com Table of Contents Ordering Information...................................................................................................................................3 AVL’S Assurance of Satisfaction...................................................................................................................3 Little Weaver................................................................................................................................................5 Home Loom..................................................................................................................................................6 Workshop Dobby Loom...............................................................................................................................7 Studio Dobby Loom......................................................................................................................................9 K-Series Loom............................................................................................................................................10 V-Series Loom............................................................................................................................................11 A-Series Loom............................................................................................................................................12 -

Understanding the Countermarche Loom

Understanding the Countermarche Loom Prepared by: Sara von Tresckow The Woolgatherers 25A N. Main St. Fond du Lac, WI 54935 [email protected] www.woolgatherers.com 1 A shaft loom forms a „shed“ or opening to insert a shuttle that passes weft back and forth to form a weave. The shed can be just one way – either rising or sinking. In this case certain threads are either lowered or lifted according to the threaded draft and the remaining threads stay in a neutral position. Rising shed looms: jack looms and most table looms Sinking shed looms: Louet David The shed can also form by moving selected warp threads up and the rest of the threads down. This forms a “countershed”. This countershed can be opened by any mechanism allowed by loom design. The most common forms of countershed are COUNTERBALANCE and COUNTERMARCHE. Counterbalance: The counterbalance loom is the oldest documented horizontal loom with treadles. The earliest drawings come from around 1000 AD and show 2 or 4 shafts attached to pulleys being moved by treadles pulling on the shaft frames. When frames are attached to pulleys, the weaver need only pull down the selected shafts and the action of the pulley will naturally pull up the other shafts. This loom literally tips the balance of the shafts to create the shed. This loom type has proven very reliable and more cloth has been woven in human history on this loom type than any other. Countermarche: At some point before 1700 the countermarche loom comes into use. It pulls EVERY treadled connection meaning that there is no chance of the tug on the pulley not bringing up the other attached shaft evenly.