Cinema That Changes the Picture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Criminal Minds: Haunted

“Haunted” Written by Erica Messer Directed by Jon Cassar © 2009 ABC Studios. All rights reserved. This material is the exclusive property of ABC Studios and is intended solely for the use of its personnel. Distribution to unauthorized persons or reproduction, in whole or in part, without the written consent of ABC Studios is strictly prohibited. PRODUCTION #502 Episode Ninety-Three Final Draft(PINK) July 29, 2009 Copyright © 2009 ABC Studios All Rights Reserved CRIMINAL MINDS “Haunted” Script Revision History DATE COLOR PAGES 7/25/2009 BLUE CAST, SET, 1-63 7/29/2009 PINK CAST, SET, 1-64 CRIMINAL MINDS “Haunted” CAST LIST ROSSI HOTCH PRENTISS MORGAN REID JENNIFER GARCIA DARRIN CALL YOUNG CALL PHARMACIST STOCK BOY * LOCAL REPORTER LIEUTENANT KEVIN MITCHELL DR. CHARLES CIPOLLA PATIENT YOUNG TOMMY WOMAN THOMAS (TOMMY) ANDERSON BILL JARVIS YOUNG BILL JARVIS FEATURED EXTRAS BANK GUARD CRIMINAL MINDS “Haunted” SET LIST INTERIORS EXTERIORS BAU JET BAU JET – DAY (STOCK) * BAU Runway High Tech Room Rossi’s Office COUNTRY ROAD - DAY PHARMACY LOUISVILLE STREET – DAY Counter Alley Aisles JARVIS HOUSE - DAY HOTCH’S APARTMENT KENTUCKY – DAY (STOCK) LOUISVILLE METRO P.D. MACHINE SHOP – DAY * CIPOLLA’S OFFICE LOUISVILLE METRO P.D. – DAY CIPOLLA’S OFFICE – DAY STREET – DAY DARRIN CALL’S APARTMENT CURBSIDE – DAY TOMMY ANDERSON’S HOUSE STERNER ORPHANAGE – DAY JARVIS HOUSE HITCHENS AVENUE - DAY MOVING SHOTS BAU SUV – Hotch & Morgan MINIVAN – Call & Ryan CRIMINAL MINDS “Haunted” TIME SPAN This episode takes place over 1 day. Teaser: Day 1 Act One: Day 1 Act Two: Day 1 Act Three: Day 1 Act Four: Day 1, Night 1 CRIMINAL MINDS "Haunted" PINK 7/29/09 1. -

Click Here to Download The

$10 OFF $10 OFF WELLNESS MEMBERSHIP MICROCHIP New Clients Only All locations Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined. Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined. Expires 3/31/2020 Expires 3/31/2020 Free First Office Exams FREE EXAM Extended Hours Complete Physical Exam Included New Clients Only Multiple Locations Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined. www.forevervets.com Expires 3/31/2020 4 x 2” ad Your Community Voice for 50 Years Your Community Voice for 50 Years RRecorPONTEPONTE VED VEDRARAdderer entertainmentEEXTRATRA!! Featuringentertainment TV listings, streaming information, sports schedules,X puzzles and more! has a new home at Here she comes, April 9 - 15, 2020 THE LINKS! 1361 S. 13th Ave., Ste. 140 ‘Mrs. America,’ Jacksonville Beach Ask about our Offering: 1/2 OFF in Cate Blanchett- · Hydrafacials All Services · RF Microneedling starring · Body Contouring · B12 Complex / Lipolean Injections FX on Hulu series · Botox & Fillers · Medical Weight Loss Cate Blanchett stars in VIRTUAL CONSULTATIONS “Mrs. America,” premiering Get Skinny with it! Wednesday on FX on Hulu. (904) 999-0977 www.SkinnyJax.com1 x 5” ad Now is a great time to It will provide your home: Kathleen Floryan List Your Home for Sale • Complimentary coverage while REALTOR® Broker Associate the home is listed • An edge in the local market LIST IT because buyers prefer to purchase a home that a seller stands behind • Reduced post-sale liability with WITH ME! ListSecure® I will provide you a FREE America’s Preferred 904-687-5146 Home Warranty for [email protected] your home when we put www.kathleenfloryan.com it on the market. -

Network Telivision

NETWORK TELIVISION NETWORK SHOWS: ABC AMERICAN HOUSEWIFE Comedy ABC Studios Kapital Entertainment Wednesdays, 9:30 - 10:00 p.m., returns Sept. 27 Cast: Katy Mixon as Katie Otto, Meg Donnelly as Taylor Otto, Diedrich Bader as Jeff Otto, Ali Wong as Doris, Julia Butters as Anna-Kat Otto, Daniel DiMaggio as Harrison Otto, Carly Hughes as Angela Executive producers: Sarah Dunn, Aaron Kaplan, Rick Weiner, Kenny Schwartz, Ruben Fleischer Casting: Brett Greenstein, Collin Daniel, Greenstein/Daniel Casting, 1030 Cole Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90038 Shoots in Los Angeles. BLACK-ISH Comedy ABC Studios Tuesdays, 9:00 - 9:30 p.m., returns Oct. 3 Cast: Anthony Anderson as Andre “Dre” Johnson, Tracee Ellis Ross as Rainbow Johnson, Yara Shahidi as Zoey Johnson, Marcus Scribner as Andre Johnson, Jr., Miles Brown as Jack Johnson, Marsai Martin as Diane Johnson, Laurence Fishburne as Pops, and Peter Mackenzie as Mr. Stevens Executive producers: Kenya Barris, Stacy Traub, Anthony Anderson, Laurence Fishburne, Helen Sugland, E. Brian Dobbins, Corey Nickerson Casting: Alexis Frank Koczaraand Christine Smith Shevchenko, Koczara/Shevchenko Casting, Disney Lot, 500 S. Buena Vista St., Shorts Bldg. 147, Burbank, CA 91521 Shoots in Los Angeles DESIGNATED SURVIVOR Drama ABC Studios The Mark Gordon Company Wednesdays, 10:00 - 11:00 p.m., returns Sept. 27 Cast: Kiefer Sutherland as Tom Kirkman, Natascha McElhone as Alex Kirkman, Adan Canto as Aaron Shore, Italia Ricci as Emily Rhodes, LaMonica Garrett as Mike Ritter, Kal Pennas Seth Wright, Maggie Q as Hannah Wells, Zoe McLellan as Kendra Daynes, Ben Lawson as Damian Rennett, and Paulo Costanzo as Lyor Boone Executive producers: David Guggenheim, Simon Kinberg, Mark Gordon, Keith Eisner, Jeff Melvoin, Nick Pepper, Suzan Bymel, Aditya Sood, Kiefer Sutherland Casting: Liz Dean, Ulrich/Dawson/Kritzer Casting, 4705 Laurel Canyon Blvd., Ste. -

Ahead in Hollywood

Una Says ➬ continued ... from previous page Previous page: Una you got some people who do the job response teams. He described that it is a team effort on Criminal Minds Riley and Jim Clemente and catch up but they are very careful after his bone marrow transplant and and I explain this to the new writers in front of the Criminal … very careful about crossing certain when his life was almost taken away as they come in and the experienced lines. So that’s the most crazy thing from him that he learned to listen writers as years go on. Some of them Minds tour bus. Above you literally have to make a decision even more to his educated gut feel initially catch on quicker than others, from left: Clemente on sometimes in a fraction of a second that he had learned over the years some of them get that feeling and set; at the sign of the Ahead in that can mean a matter of life or death of investigating sexual and violent they understand it better but I always BAU on set; and with for the victim that is out there waiting crimes. He explained that he acquired get the chance to read what they write actress AJ Cook. Below: for you to rescue them.” the knowledge to have the confidence and I get the chance to give them Familiar to millions of to pick out the details of things. He little nuanced edits, sometimes they Criminal Minds viewers, Trust in instinct went on: “I got very good at that. -

{PDF} Its a Dirty Job... : Writing Porn for Fun and Profit!

ITS A DIRTY JOB... : WRITING PORN FOR FUN AND PROFIT! Author: Katy Terrega Number of Pages: 148 pages Published Date: 01 Oct 2001 Publisher: Booklocker Inc.,US Publication Country: Bangor, United States Language: English ISBN: 9781929072231 DOWNLOAD: ITS A DIRTY JOB... : WRITING PORN FOR FUN AND PROFIT! Its a Dirty Job... : Writing Porn for Fun and Profit! PDF Book The leaders. This best-selling guide also instructs how to judge recordings and improve them to produce maximum results. By providing an analysis of photography, film, television, and computer culture, Moss uses the Holocaust as an historical case study to illustrate the ways in which visual culture can be used to bring about an awareness of history, as well as the potential for visual culture becoming a driving force for social and cultural change. Whether you are a seasoned pro or new to teaching psychology online, the tips in this book can help improve your instruction, reduce your prep time, and enhance your students' success. I therefore thought it much better, to supply the place of engravings, by letter-press description, than farther to enhance the price of a book, the object of which has been neither the acquisition of profit, nor the gratification of vanity. This book is written for any runner who: - is seeking to proactively prevent injuries - is currently injured and looking to return to running - has been previously injured and never made a return to running - is not concerned about injury prevention or rehabilitation but just wants to get faster. com cites Erica Messer as the Showrunner and longest serving writer on Criminal Minds (Criminal Minds: Cast). -

Tv Shows - 2019 Drama

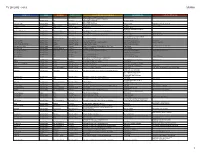

TV SHOWS - 2019 DRAMA SHOW TITLE GENRE NETWORK SEASON STATUS STUDIO / PRODUCTION COMPANIES SHOWRUNNER(S) EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS 68 Whiskey Episodic Drama Paramount Network Ordered to Series CBS TV Studios / Imagine Television Roberto Benabib Fox TV Studios / 20th Century Fox Television, 911 Episodic Drama Fox Renewed Ryan Murphy Productions Timothy P. Minear, 20th Century Fox TV / 9-1-1: Lone Star Episodic Drama Fox Ordered to Series Ryan Murphy Productions Ryan P. Murphy Brad Falchuk; Timothy P. Minear A Million Little Things Episodic Drama ABC Television Renewed ABC Studios / Kapital Entertainment DJ Nash James Griffiths A Teacher Drama FX Network Ordered To Series FX Productions Hannah M. Fidell Jed Whedon; Maurissa Tancharoen; Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. Episodic Drama ABC Television Renewed ABC Studios / Marvel Entertainment; Mutant Enemy Jeffrey Bell Alive Episodic Drama CBS Entertainment Not Picked Up CBS TV Studios Jason Tracey Robert Doherty All American Episodic Drama CW Network Renewed Warner Bros Television / Berlanti Productions Nkechi Carroll, Gregory G. Berlanti Greg Spottiswood; Leonard Goldstein; All Rise Episodic Drama CBS Entertainment Ordered to Series Warner Bros Television Michael Robin; Gil Garcetti Almost Paradise Episodic Drama WGN America Ordered to Series Electric Entertainment Gary Rosen; Dean Devlin Marc Roskin Amazing Stories Episodic Drama Apple Ordered To Series Universal Television LLC / Amblin Television Adam Horowitz; Edward Kitsis David H. Goodman Amazon/Russo Bros Project Episodic Drama Amazon Ordered To Series Amazon Studios / AGBO Anthony Russo; Joe Russo American Crime Story Episodic Drama FX Network Renewed Fox 21; FX Productions / B2 Entertainment; Color Force Ryan Murphy Brad Falchuk; D V. -

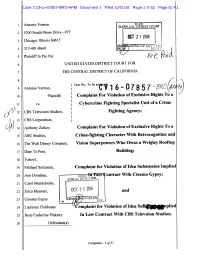

Vernon V. CBS Television

Case 2:16-cv-07857-BRO-AFM Document 1 Filed 10/21/16 Page 1 of 42 Page ID #:1 l Antonio Vernon =ICED DISTRICT 2 5300 South Shore Drive - #77 3 Chicago, Illinois 60615 OCT 2 12016 4 312-401-8669 DCPUTYC 5 PlaintiffIn Pro Per ~~ ~~ ~ ~~~ 6 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR 7 THE CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 8 Case No.: To be as~~ ~ ~ ~ o ~ ~ ~ ~ ~~~~ 9 Antonio Vernon, (~ to Plaintiff, ~, Complaint For Violation of Exclusive Rights To a ii vs. Cybercrime Fighting Specialist Unit of a Crime ~~~ 12 CBS Television Studios, Fighting Agency; 13 CBS Corporation, 14 Anthony Zuiker, Complaint For Violation of Exclusive Rights To a 15 ABC Studios, Crime-fighting Character With Retrocognition an~ 16 The Walt Disney Company, Vision Superpowers Who Owns a Wrigley Rooftop 17 Dare To Pass, Building; 18 Ya.~200 ~, 19 I Michael Seitzman, Complaint for Violation of Idea Submission Implie 20 Ann Donahue, ~ roc, p ontract With Cinema Gypsy; CLER'rt, U.J. DISIRICI 1,00RT 21 Carol Mendelsohn, 2016 22 Erica Messner, OCT 2 0 and 23 Cinema Gypsy CEN11 kl Of CALII ORNIA B'( DCPUiY 24 Laurence Fishburne ~mplaint for Violation of Idea Su~~iiplie 25 Rose Catherine Pinkney In Law Contract With CBS Television Studios; 26 Defendants) Complaint - 1 of37 Case 2:16-cv-07857-BRO-AFM Document 1 Filed 10/21/16 Page 2 of 42 Page ID #:2 1 2 Jurisdiction 3 1. This court has jurisdiction under United States Code Title 28 Part N Chapter 87 (especially 4 section 1338 —aka 28 U.S. Code § 1338) and United States Code Title 17 Chapter 5 5 (especially sections 501 and/or 506 —aka 17 U.S. -

Imani Akbar Resume

Imani Akbar Costume Designer ImaniAkbar.com Project Title Director Prod. Company/Producers “THAT GIRL LAY LAY” (Season 1) Various Nickelodeon, Will Packer Media 1/2hr Multi-cam Comedy EP: Will Packer, David Arnold Cast: Alaya High, Andrea Barber, Caleb Brown LP: Julie Tsutsui “LOOSELY EXACTLY NICOLE” (Season 2) Various Facebook Watch, 3 Arts Ent. Cast: Nicole Byer, Jacob Wysocki, EP: Christine Zander Jen D’Angelo, Kevin Bigley, Allyn Rachel LP: Debra Spidel “ME AND MEAN MARGARET” (Pilot) James Burrows NBC, Chernin Entertainment 1/2hr Multi-cam Comedy Producer: Mark Nasser Cast: Stockard Channing, Maya Erskine, LP: Suzy Greenberg Mamoudou Athie, Gavin Stenhouse “DAYLIGHT FADES” (Feature) Brad Elis Old School Pictures Cast: Rachel Miles, Allen Gardner, Producer: Mark Norris Rachel Kimsey Stylist (Unscripted and Commercials) “TOP CHEFF MASTERS” Various Bravo / EP: Nan Strait “AROUND THE WORLD IN 80 PLATES” Various Bravo / EP: Ellie Carbajal “SAMSUNG GALAXY S3” Todd Field Hungry Man/Producer: Cory Berg “GAME OF THRONES & TIME WARNER” Todd Field Smuggler/Producer: Cory Berg “CHASE BANK” Joseph Ruzer Keeper/Producer: Jase McGann “AT&T” Christopher Collins Smuggler/Producer: Billy Hopkins “MCDONALD’S” Robert Weiss HungryMan/Producer: Frank Weston “COORS LIGHT” Jeremy Barnes Ezra / Producer: Jillian Ross “GATORADE” Murray Paterson Zane / Producer: Steve Forman Assistant Costume Designer “GRAND CREW” (Pilot) Mo Marable NBCUniversal Cast: Carl Tart, Echo Kellum, EP: Phil Jackson, Dan Goor Justin Cunningham, Nicole Byer LP: Matt Nodella “THE L-WORD” -

Mark Zuelzke Resume

MARK ZUELZKE Production Designer www. markzuelzke.com Feature Films: BRING IT ON: FIGHT TO THE FINISH - Universal Pictures - Director: Billie Woodruff Producers: David Brookwell, Sean McNamara, David Buelow GLASS HOUSE: THE GOOD MOTHER - Sony / Screen Gems - Director: Steven Antin Producer: Billy Pollina, Connie Dolph NEARING GRACE - Whitewater Films - Director: Rick Rosenthal Producers: Rick Rosenthal, Susan Johnson, John Wells URBAN LEGENDS: FINAL CUT - Sony / Phoenix Pictures - Director: John Ottman Producers: Neil Moritz, Gina Matthews, Richard Rothschild, Brad Luff Additional Photography as Production Designer: THE LOVE GURU - Paramount - Director: Marco Schnabel Exec. Producers: Gary Barber, Roger Birnbaum Producers: Michael De Luca, Donald J. Lee Jr., Mike Myers HONEYMOONERS - Paramount - Director: John Schultz Producers: David Friendly, Marc Turtletaub, Julie Durk – Line Prod: Nan Morales X-MEN 2 - 20 th Century Fox - Director: Bryan Singer Exec. Producers: Avi Arad, Tom Desanto, Kevin Feige - Producers: Ralph Winter, Lauren Shuler Donner UPM: Stewart Bethune ELEKTRA - 20 th Century Fox - Director: Rob Bowman Exec. Producer: Brent O’Connor - Producers: Avi Arad, Gary Foster, Mark Steven Johnson Line Prod: Jack Murray MR. 3000 - Spyglass Entertainment / Disney - Director: Charles Stone III Producers: Gary Barber, Rodger Birnbaum, Maggie Wild – UPM: Ross Fanger A GENTLEMEN’S AGREEMENT – USA – DirectorL J. Mills Goodloe – Producer: Kimberly Braswell Line Prod: Tony Amatullo Art Director for Film (selected) : ONE NIGHT IN MIAMI – -

Determining the Effectiveness of Network Broadcast Diversity Initiative Programs Leah P

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2014 Overcoming the Diversity Ghetto: Determining the Effectiveness of Network Broadcast Diversity Initiative Programs Leah P. Hunter Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION AND INFORMATION OVERCOMING THE DIVERSITY GHETTO: DETERMINING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF NETWORK BROADCAST DIVERSITY INITIATIVE PROGRAMS By LEAH P. HUNTER A Dissertation submitted to the School of Communication in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2014 Leah P. Hunter defended this dissertation on April 2014. The members of the supervisory committee were: Jennifer M. Proffitt Professor Directing Dissertation Valliere Richard University Representative Stephen McDowell Committee Member Davis Houck Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii To Momma and Daddy. All that I am is because of you. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you Jesus!!! First, I would like to thank my family: My Mom and Dad, Ricky, Nori, Billy, Robin, Lori, Stanley, Holly, Marisa, Nozomi, Duke, Jordan, and all of my aunts, uncles, and cousins. I am so fortunate to have a family that is supportive of me. We lost my Mom at the end of my second year in the doctoral program and I was absolutely sure that I would not be able to go on. She was my best friend and was the one who encouraged me to go back to school in the first place. -

A Film by John Chester

Presents A FILM BY JOHN CHESTER RUNNING TIME: 91 minutes RATING: PG FESTIVALS 2018 Telluride Film Festival 2019 Santa Barbara International Film Festival 2018 Toronto Film Festival 2019 Atlanta Film Festival 2018 Hamptons International Film Festival 2019 Minneapolis St. Paul Film Festival 2018 Mill Valley Film Festival 2019 San Francisco International Film Festival 2018 Middleburg Film Festival 2019 Chattanooga Film Festival 2018 Vermont International Film Festival 2019 Dallas International Film Festival 2018 Philadelphia Film Festival 2019 Phoenix Film Festival 2018 Denver Film Festival 2019 DOC10 2018 Virginia Film Festival 2019 Newport Beach Film Festival 2018 St. Louis International Film Festival 2019 EarthX Film Festival 2018 Napa Valley Film Festival 2019 Princeton Environmental Film Festival 2018 DOC NYC 2019 Orcas Island Film Festival 2018 AFI Festival 2019 One Take Documentary Film Festival 2018 Hawaii International Film Festival 2019 Hamptons Doc Fest Spring Festival 2019 Sundance Film Festival 2019 Indy Film Festival LOGLINE: THE BIGGEST LITTLE FARM chronicles the eight-year quest of John and Molly Chester as they trade city living for 200 acres of barren farmland and a dream to harvest in harmony with nature. Featuring breathtaking cinematography, captivating animals, and an urgent message to heed Mother Nature’s call, THE BIGGEST LITTLE FARM provides us all a vital blueprint for better living and a healthier planet. SYNOPSIS: THE BIGGEST LITTLE FARM chronicles the eight-year quest of John and Molly Chester as they trade city living for 200 acres of barren farmland and a dream to harvest in harmony with nature. Through dogged perseverance and embracing the opportunity provided by nature's conflicts, the Chesters unlock and uncover a biodiverse design for living that exists far beyond their farm, its seasons, and our wildest imagination. -

Robert La Bonge

ROBERT LA BONGE DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY bobbylabonge.com TELEVISION FAITH UNDER FIRE (MOW) Sony Pictures TV/Lifetime Prod: Judith Verno, Craig Baumgarten Dir: Vondie Curtis-Hall Larry Rapaport GREY’S ANATOMY ABC Studios/ABC Prod: Shonda Rhimes, Krista Vernoff, Sara E. White Dir: Various (Season 14, 5 stand-alone eps.) PITCH (Season 1) 20th Century Fox/FOX Prod: Dan Fogelman, Paris Barclay, Kevin Falls Dir: Various Neal Ahern SCORPION (Season 1) CBS Television/CBS Prod: Nick Santora, Heather Kadin, Alex Kurtzman Dir: Various Robert Orci SLEEPY HOLLOW (Season 1) 20th Century Fox/FOX Prod: Ken Olin, Mark Goffman, Neil Ahern Dir: Various PRETTY LITTLE LIARS Warner Horizon/ABC Family Prod: Leslie Morgenstein, I. Marlene King Dir: Various (Seasons 5-6) Lisa Cochran-Neilan, Skip Beaudine ARMY WIVES (Seasons 3 - 7) ABC Studios/Lifetime Prod: Mark Gordon, Deborah Spera, Harry Bring Dir: Various PRIVILEGED (Season 1) Warner Bros./The CW Prod: Rina Mimoun, Bob Levy, Leslie Morgenstein Dir: Various Peter Burrell COLD CASE (Eps. 509/516) Warner Bros./CBS Prod: Jerry Bruckheimer, Meredith Stiehm Dir: Kevin Bray Merri Howard Alex Zakrzewski VICTORIA PILE (Pilot) CBS Paramount/ABC Prod: Victoria Pile, Chris Godsick Dir: Victoria Pile PRISON BREAK (Seasons 1 - 2) 20th Century Fox/FOX Prod: Nick Santora, Marty Adelstein, Neal Moritz Dir: Various Garry Brown THE “X” FILES (Seasons 6 - 9) 20th Century Fox/FOX Prod: Chris Carter, Michelle MacLaren, Harry Bring Dir: Various (2nd Unit) TELEVISION – ADDITIONAL PHOTOGRAPHY RUNAWAYS (Season 1) ABC Signature/Hulu