The Use of Local Radio Stations by Public School Systems in New England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SAGA COMMUNICATIONS, INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

2017 Annual Report 2017 Annual Letter To our fellow shareholders: Every now and then I am introduced to someone who knows, kind of, who I am and what I do and they instinctively ask, ‘‘How are things at Saga?’’ (they pronounce it ‘‘say-gah’’). I am polite and correct their pronunciation (‘‘sah-gah’’) as I am proud of the word and its history. This is usually followed by, ‘‘What is a ‘‘sah-gah?’’ My response is that there are several definitions — a common one from 1857 deems a ‘‘Saga’’ as ‘‘a long, convoluted story.’’ The second one that we prefer is ‘‘an ongoing adventure.’’ That’s what we are. Next they ask, ‘‘What do you do there?’’ (pause, pause). I, too, pause, as by saying my title doesn’t really tell what I do or what Saga does. In essence, I tell them that I am in charge of the wellness of the Company and overseer and polisher of the multiple brands of radio stations that we have. Then comes the question, ‘‘Radio stations are brands?’’ ‘‘Yes,’’ I respond. ‘‘A consistent allusion can become a brand. Each and every one of our radio stations has a created personality that requires ongoing care. That is one of the things that differentiates us from other radio companies.’’ We really care about the identity, ambiance, and mission of each and every station that belongs to Saga. We have radio stations that have been on the air for close to 100 years and we have radio stations that have been created just months ago. -

New Directions for AM

ISSUE NUMBER 684 ~THE IIVDUSTRY'S NEWSPAPER N S 1 D E: Widmann Elevated To CBS O &O VP WINTER ARBITRONS CBS VP /Owned AM Stations Nancy Widmann has been pro- FLOODING IN moted to the newly created post Baltimore: WLIF, WBSB roll upward of VP /Owned Radio Stations Boston: WBZ, WXKS -FM neck -and- and will now also oversee the neck company's FM group. She as- sumes the duties of VP /Owned Cleveland: WMMS down to 12, FM Stations Robert Hyland III, WZAK, WMJI up solidly who last week became GM for Dallas: KKDA-FM close to 10, leads KCBS -TV/Los Angeles. big Continuing as the highest- Denver: KBCO breathes down KOSI's ranking woman at CBS Radio, neck Widmann has held many execu- Detroit: WJLB rules roost, WRIF tive positions during her 15 regains AOR lead years with the company, in- Nancy Widmann Houston: KMJO holds lead as KKBQ cluding a six-year stint as VP/ Sales Manager for CBS Radio soars into second GM of WCBS-FM /New York. Spot Sales, and VP /Recruit- She also was VP/GM and N.Y. ment and Placement for CBS, rules Pittsburgh: KDKA Inc. Philadelphia: WEAZ ties WMMR at top Commented CBS Radio Divi- San Francisco: KABL almost beats sion President Bob Hosking, KGO; KMEL top contemporary New Directions For AM "Nancy's proven abilities with Tampa: WRBQ rises higher WHN Drops Country WCFL Becomes our six News and News/Talk stations, plus WCBS -FM, make Washington: WGAY takes lead, WHN Sports For All -Sports Chicago's AM Loop her eminently qualified for this WMZQ -FM vaults to third After more than 14 years in System H&G Communications has new position." Plus ratings for Nassau -Suffolk, Country, WHN /New York was combined the company's two Widmann, who oversees sev- Providence, and San Diego. -

THE WHY and Wherefore Or POOR RADIO RECEPTION

Modern radios are pack ed w ith features and refin ements that add immeasurably to radio enjoyment. Yet , no amount of radio improve - ments can increase th is enjoyment 'unless these improvements are u sed-and used properly . Ev en older radios are seldom operated to bring out the fine performance which they are WITH capable of giving . So , in justice to yourself and ~nninqhom the fi ne radio programs now being transmitted , ask yoursel f this questi on: "A m I getting as much enjoyment from my r ad io as possible?" Proper radio o per atio n re solves itself into a RADIO TUBES matter of proper tunin g. Yes , it's as simple as that . But you would be su rprised how few Hour aft er hour .. da y a nd night ... all ye ar people really know ho w t o tune a radio . In lon g . .. th e air is fill ed with star s who enter- Figure 1, the dial pointer is shown in the tain you. News broad casts ke ep you abrea st of middle of a shaded area . A certain station can be heard when the pointer covers any part of a swiftl y moving world . .. sport scast s brin g this shaded area , but it can only be heard you the tingling thrill of competition afield. enjo yably- clearl y and without distortion- Yet none of the se broadca sts can give you when the pointer is at dead center , midway between the point where the program first full sati sfaction unle ss you hear th em properl y. -

Commonwealth News Service

COMMONWEALTH 25 27 28 22 18 23 15 33 CNS National Pick Up 10 11 1,176 Stations 29 30 23 1 4 31 5 7 6 38 39 16 8 NEWS SERVICE 17 26 34 35 9 12 36 74 state/regional radio stations aired 19 32 14 20 21 CNS stories in 2005 13 37 24 1. WCDJ-FM (1) Allston 26. WMRC-AM (1) Milford 2. WMUA-FM, WFCR-FM (2) Amherst 27. WNAW-AM, WMNB-FM (2) North Adams 3. WPNI-AM, WRNX-FM (2) Amherst 28. WJDF-FM (1) Orange 4. Metro Networks, Boston 29. WBEC-AM/FM (2) Pittsfi eld 5. WAAF-FM, WEEI-AM, WRKO-AM, WVEI-AM, WQSX-FM (5) Boston 30. WBRK-AM/FM (2) Pittsfi eld 6. WBZ-AM, WBCN-FM, WODS-FM,WBMX-FM, WZLX-FM (5) Boston 31. WUHN-AM, WUPE-FM (2) Pittsfi eld 7. WERS-FM (1) Boston 32. WPRO-AM/FM, WSKO-AM, WWLI-FM (4) Providence 8. WVEI-AM, WEEI-AM (2) Boston/Worcestor 33. WESX-AM (1) Salem 9. WBET-AM (1) Brockton 34. WHMP-AM, WRSI-FM, WPVQ-FM, WAQY-FM, WHAI-FM, WLZX-FM 10. WMBR-FM (1) Cambridge (6) Springfi eld 11. WRCA-AM, WHRB-FM (2) Cambridge 35. WHYN-AM/FM, WNNZ-AM (3) Springfi eld 12. WHNP-AM (1) East Longmeadow 36. WPEP-AM (1) Taunton 13. WBSM-AM, WFHN-FM (2) Fairhaven 37. WNAN-AM, WCAI-FM (2) Woods Hole 14. WSAR-AM, WHTB-AM (2) Fall River 38. WORC-AM, WGFP-AM (2) Worcester 15. WEIM-AM (1) Fitchburg 39. -

Daytime Bandscans

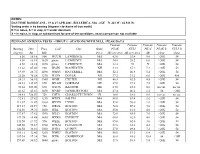

NOTES: DAYTIME BANDSCANS - 19 & 27 APR 2001 -BILLERICA, MA - (GC= 71.221 W / 42.533 N) Sorting order is by bearing (degrees clockwise of true north) N = in noise, S = in slop, U = under dominant X = in noise, in slop, or subdominant for one of the conditions, exact comparison not available PENNANT ANTENNA TESTS - GROUP 1 - STATIONS WITH NULL / PEAK DATA Pennant Pennant Pennant Pennant Pennant Bearing Dist. Freq. Call City State/ PEAK NULL PK-N PEAK R NULL R degrees km kHz Prov. dB over zero dB over zero dB ohms ohms 8.56 16.18 800 WCCM LAWRENCE MA 63.0 53.4 9.6 >20K 54 8.56 16.18 1620 pirate LAWRENCE MA 34.8 28.2 6.6 >20K 54 8.56 16.18 1670 pirate LAWRENCE MA 22.8 N X >20K 54 14.62 87.04 930 WGIN ROCHESTER NH 44.4 37.2 7.2 >20K 54 19.89 28.72 1490 WHAV HAVERHILL MA 52.2 46.8 5.4 >20K 54 22.20 78.58 1270 WTSN DOVER NH 37.2 31.2 6.0 >20K 486 24.21 56.10 1540 WGIP EXETER NH 46.8 42.0 4.8 >20K 54 24.81 139.07 870 WLAM GORHAM ME 27.0 19.2 7.8 >20K 54 36.61 322.00 620 WZON BANGOR ME 24.0 24.0 0.0 no var. no var. 41.83 43.83 1450 WNBP NEWBURYPORT MA 47.4 46.2 1.2 54 >20K 54.81 758.59 720 CHTN CHARLOTTETOWN PI 18.0 18.0 0.0 no var. -

Broadcasting Telecasting

YEAR 101RN NOSI1)6 COLLEIih 26TH LIBRARY énoux CITY IOWA BROADCASTING TELECASTING THE BUSINESSWEEKLY OF RADIO AND TELEVISION APRIL 1, 1957 350 PER COPY c < .$'- Ki Ti3dddSIA3N Military zeros in on vhf channels 2 -6 Page 31 e&ol 9 A3I3 It's time to talk money with ASCAP again Page 42 'mars :.IE.iC! I ri Government sues Loew's for block booking Page 46 a2aTioO aFiE$r:i:;ao3 NARTB previews: What's on tap in Chicago Page 79 P N PO NT POW E R GETS BEST R E SULTS Radio Station W -I -T -H "pin point power" is tailor -made to blanket Baltimore's 15 -mile radius at low, low rates -with no waste coverage. W -I -T -H reaches 74% * of all Baltimore homes every week -delivers more listeners per dollar than any competitor. That's why we have twice as many advertisers as any competitor. That's why we're sure to hit the sales "bull's -eye" for you, too. 'Cumulative Pulse Audience Survey Buy Tom Tinsley President R. C. Embry Vice Pres. C O I N I F I I D E I N I C E National Representatives: Select Station Representatives in New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington. Forloe & Co. in Chicago, Seattle, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Dallas, Atlanta. RELAX and PLAY on a Remleee4#01%,/ You fly to Bermuda In less than 4 hours! FACELIFT FOR STATION WHTN-TV rebuilding to keep pace with the increasing importance of Central Ohio Valley . expanding to serve the needs of America's fastest growing industrial area better! Draw on this Powerhouse When OPERATION 'FACELIFT is completed this Spring, Station WNTN -TV's 316,000 watts will pour out of an antenna of Facts for your Slogan: 1000 feet above the average terrain! This means . -

Annual Report of the Department of Education

Public Document No, 2 CA^y?^ tZTfie Commontoealtl) of i^a£(sac|)u^ett^ S. L. ANNUAL REPORT OF THE Department of Education Year ending November 30, 1940 Issued in Accordance with Section 2 of Chapteb 69 OF the General Laws Part I Publication op this DoctmzNT Afpboved by the Commission on Adminibtbation and Finance 1500—6-'41—6332. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION WALTER F. DOWNEY, Commissioner of Education Members of Advisory Board Ex officio The Commissioner of Education, Chairman Term Expires 1940. Alexander Brin, 55 Crosby Road, Newton 1940. Thomas H. Sullivan, Slater Building, Worcester 1941. Mrs. Anna M. Power, 15 Ashland Street, Worcester 1941. Kathryn a. Doyle, 99 Armour Street, New Bedford 1942. Mrs. Flora Lane, 27 Goldthwait Street, Worcester 1942. John J. Walsh, 15 Pond View Avenue, Jamaica Plain George H. Varney, Business Agent Division of Elementary and Secondary Education and State Teachers Colleges PATRICK J. SULLIVAN, Director Supervisors Alice B. Beal, Supervisor of Elementary Education A. Russell Mack, Supervisor of Secondary Education Raymond A. FitzGerald, Supervisor of Educational Research and Statistics and In- terpreter of School Law Thomas A. Phelan, Supervisor in Education of Teacher Placement Daniel J. Kelly, Supervisor of Physical Education Martina McDonald, Supervisor in Education Ralph H. Colson, Assistant Supervisor in Education Ina M. Curley, Supervisor in Education Philip G. Cashman, Supervisor in Education Presidents of State Teachers Colleges and the Massachusetts School of Art John J. Kelly, Bridgewater James Dugan, Lowell Charles M. Herlihy, Fitchburg Grover C. Bowman, North Adams Martin F. O'Connor, Framingham Edward A. Sullivan, Salem Annie C. Crowell (Acting), Hyannis Edward J. -

November 21, 2014 Vol. 118 No. 47

VOL. 118 - NO. 47 BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, NOVEMBER 21, 2014 $.35 A COPY Thanksgiving vs. Roseland and Massport Celebrate Opening of the Big Box Company PORTSIDE AT EAST PIER BUILDING 7 by Nicole Vellucci Ribbon-Cutting Held for Luxury Residential and Retail Complex in East Boston Thanksgiving, a Roseland, a subsidiary of day synonymous Mack-Cali Realty Corpora- with the word fam- tion (NYSE: CLI), in partner- ily in American cul- ship with the Massachusetts ture, has become Port Authority (Massport), more about the dol- hosted a ribbon-cutting for lar than together- the opening of Portside at ness. As a child, our East Pier Building 7, its flag- Thanksgiving ship luxury residential and preparations began retail complex located at 50 weeks prior to the Lewis Street in East Boston. main event with planning the menu, inviting family and Joined by Senator Anthony friends and endless trips to the grocery store. My father Petruccelli and State Rep. would post the dinner menu on our kitchen refrigerator Carlo Basile, Roseland and and everyone was asked to add their requests. Turkey day Massport celebrated the morning began with naming our bird (or birds since one completion of the initial thirty-pound turkey was not enough because you never building in East Boston’s first knew who would stop by) and preparation of all the deli- residential waterfront devel- Left to right: State Senator Anthony Petruccelli, cious accompaniments. Besides the wonderful aroma of this opment project in decades. Roseland President Marshall Tycher, City Councilor Sal feast filling our home, what I remember most is all the Portside at East Pier Build- LaMattina, State Rep Carlo Basile, BRA Director Brian Golden and Massport CEO Tom Glynn. -

Collicot Elementary School 80 Edge Hill Road, Milton, MA 02186

Milton Public Schools Elementary Parent/Guardian & Student Handbook 2011-2012 Collicot Elementary School 80 Edge Hill Road, Milton, MA 02186 Respect, Achievement, Citizenship Collicot Elementary School Message from the Principal: At the Collicot School there is a commitment to academic excellence and high standards for administrators, teachers, and students. The dedicated and creative Collicot teachers and staff are committed to maximizing the individual potential of each child. Through a wide variety of challenging activities and experiences, we strive to provide a strong academic foundation and a love of learning in a secure, safe, and stimulating environment that values individual differences. The Collicot School promotes Milton Public Schools’ core values: High Academic Achievement for All Excellence in the Classroom Collaborative Relationships and Communication Respect for Human Differences Risk Taking and Innovation for Education Family interest and involvement are at the foundation of the Collicot School’s success. We look forward to nurturing this relationship and to continuing this educational partnership. Table of Contents District Directory Page 3-6 Collicot Elementary School Procedures Pages Collicot School Hours, Early Arrival/ Extended Day Program, Arrival and Dismissal Procedures, Early 6-8 Dismissal, Late Student Pick-up Policy, Lunch Milton Public Schools Administrative Information Pages School Cancellations, Home/School Communication, Attendance, Residency, Birthdays, Homework 9-13 and Reading Policy, Family Educational -

SAGA COMMUNICATIONS, INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

2016 Annual Report 2016 Annual Letter To our fellow shareholders: Well…. here we go. This letter is supposed to be my turn to tell you about Saga, but this year is a little different because it involves other people telling you about Saga. The following is a letter sent to the staff at WNOR FM 99 in Norfolk, Virginia. Directly or indirectly, I have been a part of this station for 35+ years. Let me continue this train of thought for a moment or two longer. Saga, through its stockholders, owns WHMP AM and WRSI FM in Northampton, Massachusetts. Let me share an experience that recently occurred there. Our General Manager, Dave Musante, learned about a local grocery/deli called Serio’s that has operated in Northampton for over 70 years. The 3rd generation matriarch had passed over a year ago and her son and daughter were having some difficulties with the store. Dave’s staff came up with the idea of a ‘‘cash mob’’ and went on the air asking people in the community to go to Serio’s from 3 to 5PM on Wednesday and ‘‘buy something.’’ That’s it. Zero dollars to our station. It wasn’t for our benefit. Community outpouring was ‘‘just overwhelming and inspiring’’ and the owner was emotionally overwhelmed by the community outreach. As Dave Musante said in his letter to me, ‘‘It was the right thing to do.’’ Even the local newspaper (and local newspapers never recognize radio) made the story front page above the fold. Permit me to do one or two more examples and then we will get down to business. -

New Solar Research Yukon's CKRW Is 50 Uganda

December 2019 Volume 65 No. 7 . New solar research . Yukon’s CKRW is 50 . Uganda: African monitor . Cape Greco goes silent . Radio art sells for $52m . Overseas Russian radio . Oban, Sheigra DXpeditions Hon. President* Bernard Brown, 130 Ashland Road West, Sutton-in-Ashfield, Notts. NG17 2HS Secretary* Herman Boel, Papeveld 3, B-9320 Erembodegem (Aalst), Vlaanderen (Belgium) +32-476-524258 [email protected] Treasurer* Martin Hall, Glackin, 199 Clashmore, Lochinver, Lairg, Sutherland IV27 4JQ 01571-855360 [email protected] MWN General Steve Whitt, Landsvale, High Catton, Yorkshire YO41 1EH Editor* 01759-373704 [email protected] (editorial & stop press news) Membership Paul Crankshaw, 3 North Neuk, Troon, Ayrshire KA10 6TT Secretary 01292-316008 [email protected] (all changes of name or address) MWN Despatch Peter Wells, 9 Hadlow Way, Lancing, Sussex BN15 9DE 01903 851517 [email protected] (printing/ despatch enquiries) Publisher VACANCY [email protected] (all orders for club publications & CDs) MWN Contributing Editors (* = MWC Officer; all addresses are UK unless indicated) DX Loggings Martin Hall, Glackin, 199 Clashmore, Lochinver, Lairg, Sutherland IV27 4JQ 01571-855360 [email protected] Mailbag Herman Boel, Papeveld 3, B-9320 Erembodegem (Aalst), Vlaanderen (Belgium) +32-476-524258 [email protected] Home Front John Williams, 100 Gravel Lane, Hemel Hempstead, Herts HP1 1SB 01442-408567 [email protected] Eurolog John Williams, 100 Gravel Lane, Hemel Hempstead, Herts HP1 1SB World News Ton Timmerman, H. Heijermanspln 10, 2024 JJ Haarlem, The Netherlands [email protected] Beacons/Utility Desk VACANCY [email protected] Central American Tore Larsson, Frejagatan 14A, SE-521 43 Falköping, Sweden Desk +-46-515-13702 fax: 00-46-515-723519 [email protected] S. -

Sheigra Dxpedition Report

Sheigra DXpedition Report 12 th to 25 th October 2019 - with Dave Kenny & Alan Pennington This was the 58th DXpedition to Sheigra in Sutherland on the far north western tip of the Scottish mainland, just south of Cape Wrath. DXers made the first long drive up here in 1979, so this we guess, was the 40 th anniversary? And the DXers who first made the trip to Sheigra in 1979 to listen to MW would probably notice little change here today: the single-track road ending in the same cluster of cottages, the cemetery besides the track towards the sea and, beyond that, the machair in front of Sheigra’s sandy bay. And surrounding Sheigra, the wild windswept hillsides, lochans and rocky cliffs pounded by the Atlantic. (You can read reports on our 18 most recent Sheigra DXpeditions on the BDXC website here: http://bdxc.org.uk/articles.html ) Below: Sheigra from the north: Arkle and Ben Stack the mountains on the horizon. Once again we made Murdo’s traditional crofter’s cottage our DX base. From here our long wire Beverage aerials can radiate out across the hillsides towards the sea and the Americas to the west and north west, and eastwards towards Asia, parallel to the old, and now very rough, peat track which continues on north east into the open moors after the tarmac road ends at Sheigra. right: Dave earths the Caribbean Beverage. We were fortunate to experience good MW conditions throughout our fortnight’s stay, thanks to very low solar activity. And on the last couple of days we were treated to some superb conditions with AM signals from the