Tourism Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City Limits London.Pdf

City Limits A resource flow and ecological footprint analysis of Greater London Project Partners Chartered IWM (EB) The Institution of Institution Civil Engineers of Wastes www.ice.org.uk Management Environmental Body The Institution of Civil Engineers IWM (EB) is a registered environmental body that sponsors original (ICE) is the pre-eminent research, development, education and information dissemination engineering institution in the projects in furtherance of professional and sustainable waste world. It has 78,000 members and provides a voice for civil management practices. engineering, professional development and promoting best practice in the industry. In 2000, ICE and CIWM agreed to instigate and co-ordinate a programme of activities funded by landfill tax credits, of which City Limits forms part. Biffaward The Chartered Institution www.biffaward.org of Wastes Management In 1997 Biffa Waste www.ciwm.co.uk Services agreed to donate The Chartered Institution of Wastes landfill tax credits to the Management (CIWM) is the pre-eminent Royal Society for Nature Conservation (RSNC) to administer under body in the UK engaged in waste management issues. It the fund name Biffaward. To date, Biffaward has distributed more represents over 4,000 professional waste managers and aims to than £44m million to 554 projects throughout the UK. protect and enhance the environment through developing scientific, technical and management standards. City Limits is a natural follow-on to CIWM's Millenium Competition and its interest in improving the quality of data available for strategic decision-making in the management of London's wastes. Greater Best Foot Forward Ltd London www.bestfootforward.com Authority Best Foot Forward Limited (BFF) is a www.london.gov.uk sustainability consultancy based in Oxford. -

Menu (Coreldraw File)

Menu INDO CHINESE CORNER Chicken Fried Rice 5.99 Chicken Hakka Noodle 7.50 Indian Restaurant Chilly Chicken 7.99 Chicken Manchurian 7.99 Contact: Sanu Thomas Chilly Paneer 7.99 Paneer Manchurian 7.99 Phone: (214) 250-0328 for Special Catering Prices Gobi Manchurian 7.99 Address: 3656 Old Denton Rd, Carrollton, TX 75007 VEGETARIAN CORNER Sambar 3.99 Moru 3.99 Thoran 5.99 Aviyal 5.99 Onion Thiyal 7.49 Mango Mappas 7.99 Paneer Butter Masala 7.99 Paneer Mutter Masala 7.99 Palak Paneer (As Per Order) 8.49 Bhindi Masala (AS Per Order) 8.49 Green Peas Curry (As Per Order) 7.99 Kadala Curry (As Per Order) 7.99 BAY LEAF SPECIAL Masala Dosa 6.99 Thattu Dosa 0.80 Appam 0.70 Kappa 4.99 Tripe (Poti) 8.49 APPETIZERS FISH SELECTION INDIAN BREADS Parippu Vada 0.80 Fish Curry 9.49 Chapati 0.80 Banana Fry 0.99 Fish Molee (As Per Order) 9.99 Porotta 0.99 Veg Puffs 1.49 Fish Curry Alleppey Style 9.99 Samosa 0.99 Fish Fry - Sardine 1.25 BEVERAGES Beef Puffs 1.49 Fish Fry - Butterfish 2.99 Sharjah Shake 6.99 Beef Cutlet 1.25 Fish Fry - Pomfret 2.49 Mango Shake 6.99 m o c Catfish Curry (Alleppey Style) Mango Lassi 5.49 . s (As Per Order) 9.99 Plain Lassi 4.49 e CHICKEN SPECIALTIES v i Tilapia (Alleppey Style) Vanilla Milk Shake 5.99 l Chicken Biriyani 5.99 o - (As per Order) 9.99 Extractor Carrot Juice 6.49 t Chicken Curry 7.49 r Tea & Coffee 1.99 a Fry Chicken 7.99 m s Butter Chicken 7.99 MUTTON SELECTION . -

The Gulai House. the House of Spices. Often Described As Spicy, Fragrant

Welcome to the Gulai House. The house of spices. Often described as spicy, fragrant and flavourful, Malaysian cuisine draws from a melting pot of spices and herbs from the old spice routes of Asia, greatly influenced by neighbouring Indonesia, India, China and the Middle East. Incorporating only the freshest ingredients, Malaysian cooking uses fresh herbs such as serai (lemongrass), pandan (screw pine leaves), and kaffir lime leaves, as well as lesser known ones such as daun kemangi (a type of basil), daun kesum (laksa leaf), nutmeg, kunyit (turmeric) and bunga kantan (wild ginger buds). Traditional spices such as cumin and coriander are used to complement the Indian and Chinese spices such as pepper, cardamom, star anise and fenugreek. Fresh herbs and dried spices are normally pounded together to make a fine paste and are then cooked in oil. Fresh coconut milk is often added to create a creamy flavour to the dishes. Take a rich culinary journey into the intriguing world of spices. SELAMAT MENJAMU SELERA Pembuka Selera / Appetiser Sup / Soup Channa Paneer 48 Sup Ayam Kampung 52 pressed cottage cheese, chickpeas, capsicum, cucumber, winter melon, soy skin and mushroom tomato and onion A perfect combination of chicken with the right amount of herbs makes the soup rich and full of flavour. A remedy for those under the weather, a comfort for those in good health. Kerabu Isi Ketam 60 Region: Melaka Malay crab meat salad, young papaya, pomelo, cucumber and island herbs Sup Ekor Berempah 58 Malay spiced oxtail soup with root vegetables Salad -

Jet2.Com and Jet2holidays Launch Flights and Holidays to Sardinia for Summer 22

Jet2.com and Jet2holidays launch flights and holidays to Sardinia for Summer 22 1st April 2021: Jet2.com and Jet2holidays have today announced the launch of flights and holidays to Sardinia for Summer 22 from four UK bases, with the first flights departing at the start of May 2022. The addition of Sardinia for Summer 22 comes in response to demand from UK holidaymakers and will see the leading leisure airline and package holiday specialist operate six weekly flights from the UK. Jet2.com and Jet2holidays will operate to Sardinia from Birmingham, Leeds Bradford, Manchester and London Stansted Airports, with flights operating into Olbia Airport. This opens up the east coast of Sardinia and a range of resorts which host some of the best beaches in Europe. Sardinia offers customers the most authentic of Italian experiences and is on many people’s bucket list of must-see European beach destinations. With snow-white sand sloping into glimmering turquoise waters, customers can head to the Costa Smeralda for a glamorous seaside experience or head south of Olbia for a holiday with an authentic slant. Jet2holidays, the UK’s leading operator to Europe, is launching with a wide selection of hotels on sale, the majority enjoying a 4 & 5-star rating. Families and groups can also choose the privacy of a villa holiday with all the benefits of a package holiday, by booking through Jet2Villas. Resorts on sale in Sardinia include Porto Cervo, Baia Sardinia, Budoni, San Teodoro, Cannigione, San Pantaleo, Orosei and Pittulongu, as well as city breaks booked through Jet2CityBreaks to Olbia. -

Fundação Getulio Vargas Escola De Administração De Empresas De São Paulo

FUNDAÇÃO GETULIO VARGAS ESCOLA DE ADMINISTRAÇÃO DE EMPRESAS DE SÃO PAULO MASCHA SÖRENSEN NATION BRANDING THROUGH MEGA-EVENTS AND THE IMPACT ON TOURISM DEVELOPMENT IN THE HOST COUNTRY: A Study on the 2014 FIFA World Cup in Brazil SÃO PAULO 2016 FUNDAÇÃO GETULIO VARGAS ESCOLA DE ADMINISTRAÇÃO DE EMPRESAS DE SÃO PAULO MASCHA SÖRENSEN NATION BRANDING THROUGH MEGA-EVENTS AND THE IMPACT ON TOURISM DEVELOPMENT IN THE HOST COUNTRY: A Study on the 2014 FIFA World Cup in Brazil Thesis presented to Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo of Fundação Getulio Vargas, as a requirement to obtain the title of Master in International Management (MPGI). Knowledge Field: Marketing Adviser: Prof. Dr. Luís Henrique Pereira SÃO PAULO 2016 Sörensen, Mascha. Nation branding through mega-events and the impact on tourism development in the host country: a study on the 2014 FIFA World Cup in Brazil / Mascha Sörensen. - 2016. 114 f. Orientador: Luís Henrique Pereira Dissertação (MPGI) - Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo. 1. Eventos especiais. 2. Copa do Mundo (Futebol) - 2014. 3. Turismo. 4. Brasil - Relações exteriores. I. Pereira, Luís Henrique. II. Dissertação (MPGI) - Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo. III. Título. CDU 379.85(81) MASCHA SÖRENSEN NATION BRANDING THROUGH MEGA-EVENTS AND THE IMPACT ON TOURISM DEVELOPMENT IN THE HOST COUNTRY: A Study on the 2014 FIFA World Cup in Brazil Thesis presented to Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo of Fundação Getulio Vargas, as a requirement to obtain the title of Master in International Management (MPGI). Knowledge Field: Marketing Approval Date: 14/09/2016 Committee Members: ________________________________ Prof. -

London Tourism Report 2013-2014 Contents

LONDON TOURISM REPORT 2013-2014 CONTENTS SECTION 1 London tourism trends 2013 p. 06 SECTION 2 International visits to London p. 16 SECTION 3 Domestic visits to London p. 28 SECTION 4 London’s connectivity p. 36 SECTION 5 London’s hotel industry p. 42 SECTION 6 London’s visitor attractions and theatres p. 50 SECTION 7 The forecast for tourism in London p. 58 LONDON TOURISM REVIEW | 3 NORTH AMERICA AND EUROPE ACCOUNT FOR The USA is London's largest visit market, 80% its 1.89 million OF ALL represented 11.2% OVERSEAS VISITS of all visits in 2013 This equated to 16.8 million overseas visits in 2012 spending a total of £11.6 billion over 97.4 million nights 29.1 MILLION HEADLINES FOR £14.1 BILLION Staying overseas and domestic visitors, generating almost 1,218 In expenditure LONDON HOTELS PROVIDING NEARLY £ £ 12.3 MILLION £ £ 117,000 VISITORS ROOMS £ £ £ £ £ 42.7 MILLION £2.8 from within the uk in 2013 ROOM BILLION spending a total of £2.8 billion NIGTHS A YEAR over 27.4 million nights ONE OF THE BEST WITH 344 DIRECT LINKS CONNECTED CITIES IN THE WORLD TO A WIDE RANGE OF SOURCE MARKETS TOP 3 NORTH 1.89 MILLION OVERSEAS AMERICA VISITS LONDON VISIT MARKETS 262 FRANCE 1.87 MILLION RECEIVED MILLION VISITS GERMANY 1.34 MILLION VISITS DAY VISITS IN 2013 4 | LONDON TOURISM REVIEW LONDON TOURISM REVIEW | 5 PHOTO SECTION 1 LONDON TOURISM TRENDS 2013 London’s tourism economy is dominated by overseas visitors. In 2013 overseas visitors accounted for 58% of visits, but more significantly, they accounted for 78% of nights and 80% of expenditure. -

Kuaghjpteresalacartemenu.Pdf

Thoughtfully Sourced Carefully Served At Hyatt, we want to meet the needs of the present generation without compromising what’s best for future generations. We have a responsibility to ensure that every one of our dishes is thoughtfully sourced and carefully served. Look out for this symbol on responsibly sourced seafood certified by either MSC, ASC, BAP or WWF. “Sustainable” - Pertaining to a system that maintains its own viability by using techniques that allow for continual reuse. This is a lifestyle that will inevitably inspire change in the way we eat and every choice we make. Empower yourself and others to make the right choices. KAYA & BUTTER TOAST appetiser & soup V Tauhu sambal kicap 24 Cucumber, sprout, carrot, sweet turnip, chili soy sauce Rojak buah 25 Vegetable, fruit, shrimp paste, peanut, sesame seeds S Popiah 25 Fresh spring roll, braised turnip, prawn, boiled egg, peanut Herbal double-boiled Chinese soup 32 Chicken, wolfberry, ginseng, dried yam Sup ekor 38 Malay-style oxtail soup, potato, carrot toasties & sandwich S Kaya & butter toast 23 White toast, kaya jam, butter Paneer toastie 35 Onion, tomato, mayo, lettuce, sour dough bread S Roti John JP teres 36 Milk bread, egg, chicken, chili sauce, shallot, coriander, garlic JPt chicken tikka sandwich 35 Onion, tomato, mayo, lettuce, egg JPt Black Angus beef burger 68 Coleslaw, tomato, onion, cheese, lettuce S Signature dish V Vegetarian Prices quoted are in MYR and inclusive of 10% service charge and 6% service tax. noodles S Curry laksa 53 Yellow noodle, tofu, shrimp, -

The River Thames: London's Riparian Highway

CHAPTER 8 The River Thames: London’s Riparian Highway Simon Curtis Introduction ‘Kingdoms may come, kingdoms may go; whatever the end may be, Old Father Thames keeps rolling along; down to the mighty sea’ (Wallace and O’Hogan 1933). London’s famous river has long been the subject of reverence and worship and the deified figure ofOld Father Thames symbolises the spiritual hold which this great river has on the city’s culture and people. The Thames artic- ulates the city; it is its artery and lifeblood and its most definitive geographi- cal feature. Crossed by 33 bridges, connecting the north and south banks of London, the river offers a lens into over 2,000 years of human occupa- tion. A voyage along the river is a remarkable experience enjoyed by tens of thousands of visitors and Londoners every day, the most evocative symbol of London’s stunning heritage and its post-1990 renaissance, re-establishing How to cite this book chapter: Curtis, S. 2019. The River Thames: London’s Riparian Highway. In: Smith, A. and Graham, A. (eds.) Destination London: The Expansion of the Visitor Economy. Pp. 165–182. London: University of Westminster Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.16997/ book35.h. License: CC-BY-NC-ND 166 Destination London Figure 8.1: The View of the River Thames from Switch House, part of Tate Modern (Photo: Tristan Luker). itself, in the eyes of many global commentators, as the world’s greatest city (Pricewaterhouse Coopers 2016). The River Thames is effectively London’s largestopen space, despite the pres- ence of the city’s numerous Royal Parks. -

Heritage Marketing

Heritage Marketing Shashi Misiura AMSTERDAM • BOSTON • HE DELBERG • LONDON • NEW YORK • OXFORD PARIS • SAN D EGO • SAN FRANCISCO • SINGAPORE • SYDNEY • T OKYO Butterworth-Heinemann is an imprint of Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann is an imprint of Elsevier Linacre House, Jordan Hill, Oxford OX2 8DP 30 Corporate Drive, Suite 400, Burlington, MA 01803 First published 2006 Copyright © 2006, Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced in any material form (including photo- copying or storing in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the copyright holder except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London, England W1T 4LP. Applications for the copyright holder’s written permission to reproduce any part of this publication should be addressed to the publisher Permissions may be sought directly from Elsevier’s Science & Technology Rights Department in Oxford, UK: phone: (+44) 1865 843830, fax: (+44) 1865 853333, e-mail: [email protected]. You may also complete your request on-line via the Elsevier homepage (http://www.elsevier.com), by selecting ‘Customer Support’ and then ‘Obtaining Permissions’ British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in -

UK Office July 2020 TDC Report Prepared By: Venessa Alexander UK Director

UK Office July 2020 TDC Report Prepared by: Venessa Alexander UK Director Tour Operators Trailfinders – We spoke with Rachel Webb, Destination Manager for Florida at Trailfinders and were advised that the Trailfinders Product team and other non-customer facing departments continue to work from home. But I'm pleased to say that, in a step towards normality, their travel centres in England, Wales and Ireland have re-opened their doors to their clients again, with all the necessary precautions in place, and their 3 travel centres in Scotland were set to re-open again at the beginning of July. They have now taken the decision to cancel all US departures up to 1 Aug 20 and Rachel suspects more will be cancelled beyond this. The company strategy very much remains to encourage their clients to re-book rather than cancel and as they get more product on sale, they are seeing more success. They continue to be able to book flights out of range. However, there are still gaps in their programme if their contact has been furloughed so they are having trouble securing a contract. Their receptive partners are also facing similar difficulties securing rates and then having the resources available to load. While they’ve seen a lot of interest in Florida as a whole, much of the business is being driven to Orlando where much product is on sale to the end of 2021 or, in some cases, into 2022. Currently, there's not the same amount of product on sale as usual in St Pete/Clearwater so the numbers booking are much smaller. -

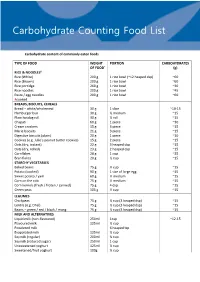

Carbohydrate Counting List

Tr45 Carbohydrate Counting Food List Carbohydrate content of commonly eaten foods TYPE OF FOOD WEIGHT PORTION CARBOHYDRATES OF FOOD* (g) RICE & NOODLES# Rice (White) 200 g 1 rice bowl (~12 heaped dsp) ~60 Rice (Brown) 200 g 1 rice bowl ~60 Rice porridge 260 g 1 rice bowl ~30 Rice noodles 200 g 1 rice bowl ~45 Pasta / egg noodles 200 g 1 rice bowl ~60 #cooked BREADS, BISCUITS, CEREALS Bread – white/wholemeal 30 g 1 slice ~10-15 Hamburger bun 30 g ½ medium ~15 Plain hotdog roll 30 g ½ roll ~15 Chapati 60 g 1 piece ~30 Cream crackers 15 g 3 piece ~15 Marie biscuits 21 g 3 piece ~15 Digestive biscuits (plain) 20 g 1 piece ~10 Cookies (e.g. Julie’s peanut butter cookies) 15 g 2 piece ~15 Oats (dry, instant) 22 g 3 heaped dsp ~15 Oats (dry, rolled) 23 g 2 heaped dsp ~15 Cornflakes 28 g 1 cup ~25 Bran flakes 20 g ½ cup ~15 STARCHY VEGETABLES Baked beans 75 g ⅓ cup ~15 Potato (cooked) 90 g 1 size of large egg ~15 Sweet potato / yam 60 g ½ medium ~15 Corn on the cob 75 g ½ medium ~15 Corn kernels (fresh / frozen / canned) 75 g 4 dsp ~15 Green peas 105 g ½ cup ~15 LEGUMES Chickpeas 75 g ½ cup (3 heaped dsp) ~15 Lentils (e.g. Dhal) 75 g ½ cup (3 heaped dsp) ~15 Beans – green / red / black / mung 75 g ½ cup (3 heaped dsp) ~15 MILK AND ALTERNATIVES Liquid milk (non-flavoured) 250ml 1cup ~12-15 Flavoured milk 125ml ½ cup Powdered milk 6 heaped tsp Evaporated milk 125ml ½ cup Soymilk (regular) 200ml ¾ cup Soymilk (reduced sugar) 250ml 1 cup Unsweetened yoghurt 125ml ½ cup Sweetened/fruit yoghurt 100g ⅓ cup TYPE OF FOOD WEIGHT PORTION CARBOHYDRATES OF -

Improvement of Flat Bread Processing and Properties by Enzymes

Improvement of flatbread processing and quality by enzymes Lutz Popper, Head R & D Flatbread feeds the world Bagebröd, Sweden; Bannock, Scotland; Bolo do caco, Madeira, Portugal; Borlengo, Italy; Farl, Ireland and Scotland; Flatbrød, Norway ; Flatkaka, Iceland; Focaccia, Italy; Ftira, Malta; Lagana, Greece; Lefse, Norway; Lepinja, Croatia, Serbia; Lepyoshka, Russia; Pita, Hungary; Flatbrød, Norway; Podpłomyk, Poland; Pane carasau, Sardinia; Piadina, Italy; Pita, Greece; Pită/Lipie/Turtă, Romania; Pissaladière, France; Pizza, Italy; Podpłomyk, Poland; Posúch, Slovakia; Părlenka, Bulgaria; Rieska, Finland; Somun, Lepina, Bosnia and Herzegovina; Spianata sarda, Sardinia; Staffordshire oatcake, England; Tigella, Italy; Torta, Spain; Torta al testo, Umbria, Italy; Torta de Gazpacho, Spain; Tunnbröd, Sweden; Yemeni lahoh; Barbari, Iran; Bataw, Egypt; Bazlama, Turkey; Gurassa, Sudan; Harsha, Morocco; Khebz, Levant; Khubz, Arabian Peninsula; Lahoh, Northern Somalia, Djibouti, Yemen; Lebanese Bread, Lebanon; Muufo, Somalia; Malooga, Yemen; M'lawi, Tunisia; Chapati, Swahili coast, Uganda; Markook, Levant; Matzo, Israel; Murr, Israel; Pita, Eastern Mediterranean, Turkey and Middle East; Sangak, Iran; Taftan, Iran; Khubz, Arabian Peninsula; Yufka, Dürüm, Turkey; Lavash, Armenia; Matnakash, Armenia; Pogača, Balkans and Turkey; Shotis Puri, Georgia; Tonis Puri, Georgia; Afghan bread or Nan, Afghanistan; Aloo paratha, India and Pakistan; Akki rotti, India; Aparon, Philippines; Bánh, Vietnam; Bakarkhani, Indian subcontinent; Bhatura, Indian subcontinent;