Passports to Privilege: the English-Medium Schools in Pakistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

07. Hallmark 2011-12.Pdf

Know that the life of this world is only play and amusement pomp and mutual boasting among you, and rivalry in respect of wealth and children, as the likeness of vegetation after rain, thereof the growth is pleasing to the tiller; afterwards it dries up and you see it tutrning yellow: then it becomes straw. But in the Hereafter (there is) Forgiveness from Allah and (His) Good Pleasure (for the believers, good-doers), whereas the life of this worls is only a deceiving enjoyment Al-Hadeed 57:20 Army Burn Hall College for Boys The Hallmark 2011-12 Q U M O A N ND ON ASCE CONTENTS Message of the Chairman Board of Governors ....................................................................................... 7 Message of the Deputy Chairman Board of Governors ......................................................................... 9 Principal’s Message .................................................................................................................................... 10 From the Editor’s Pen ................................................................................................................................ 12 The College Faculty ................................................................................................................................... 14 VIEWS & REVIEWS ................................................................................................................................ 18 ANNUAL DAY AND PRIZE DISTRIBUTION Principal’s Report - Annual Parents Day and Prize Distribution Ceremony -

Chapter-Ii Historical Background of Public Schools

C H APTER -II HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF PUBLIC SCHOOLS 2.0 INTRODUCTORY REMARKS The purpose of this chapter is to give an account of historical back ground of Public Schools, both in England and in India. It is essential to know the origin and development of Public Schools in England, as Public Schools in India had been transplanted from England. 2.1 ORIGIN OF THE TERM PUBLIC SCHOOL The term 'Public School' finds its roots in ancient times. In ancient time kings and bishops used to run the schools for the poor. No fee was charged. All used to live together. It was a union of 'classes'. The expenses were met by public exchequer. Thus the name was given to these schools as Public Schools. 2.2 ESTABLISHMENT OF FIRST PUBLIC SCHOOLS William of Wykeham, Bishop of Winchester established 'Saint Marie College' at Winchester in 1382. This foundation made a crucial departure from previous practice and thus, has a great historical importance. All the previous schools had been ancillary to other establishments; they Kod been established as parts of cathedrals, collegiate churches, monasteries, chantries, hospitals or university colleges. The significance of this college is its independent nature. 17 Its historian, A.F. Leach says "Thus for the first time a school was established as a sovereign and independent corporation, existing by and for itself, self-centered and self-governed."^ The foundation of Winchester College is considered to be the origin of the English Public School because of three conditions: 1. Pupils were to be accepted from anywhere in England (though certain countries had priority). -

Army Burn Hall College for Boys Admission Register Mar 1987 To

Army Burn Hall College for Boys Admission Register Mar 1987 to Dec 1995 Class to Class from Date of Date of Name of Ser Ser No. Date of Birth Fathers Name Previous Occupation Address which which with Remarks admission Student Admitted draw withdrawal Late Tc issued on 18.5.91 Brig Muhammad 20-12-1974 Ahsan khan House No. 4/1, Sheryar (twentieth Dec (Guardian) Mr Pak- Ints public Late Sector iv, Ahsan khan nineteen seventy Fsc 1sty 1 3.3.87 87.01 Sultan school khalabat 8 Blue (SIS) 16.5.91 four) (P.M) Abbottabad (Agriculture) township Muhammad (B) khan haripur F.G Public Tc issued on parents 87.02 06.01.1975 (Sixth Late C.M. Naqvi 28, Bazar Area Muhammad School request Brig 2 16.4.87 January Nineteen Guardian Brig Late Gujranwala 8 Blue (SIS) 3 1.3.88 Rizwan Ullah Gujranwala (B) seventy five) C.M. Rafi cantt cantt 02.10.1974 1122/B, peoples 87.03 Chaudhry Dir. public (Second October colony No-2 3 16.4.87 Irfan Akram Muhammad school Farmer 8 Blue (SIS) nineteen seventy fawwara chowk (B) Akram Faisalabad five four) Faisalabad 87.04 17.6.1974 Tc issued at parents request House No.2A, (B) Asad Ali (Seventeenth June Mr Tayeb Ali Isl college for Brig 4 15.3.87 Service St-35 sector F- 8Blue (SIS) 8Blue (SIS) 9.4.87 sheikh nineteen seventy sheikh boys G6/3 Isl 6/1 Islamabad four Brig F.G Gov. Boys Village Kot 10.01.1975 ((tenth 87.05 Salman Muhammad public high nizamuddin via: 5 04.3.87 January nineteen Army officer 8 Red (STS) (DS) Goheer Shafique school shahkot seventy five) Goheer Abbottabad Sheikhpura 6 5.3.87 Naeem Akbar Haji Ali Akbar Saraf -

Duke-UNCCH Religion & Science Symposium

Duke-UNCCH Religion & Science Symposium KENAN-BIDDLE GRANT PROPOSAL Abdul Latif, Duke Class of 2016 Tafadzwa Matika, UNC-CH Class of 2016 Kehaan H Manjee, Duke Class of 2016 Advisor: Dr. Christy Lohr Sapp, Associate Dean of Religious Life, Duke University October 21st 2013 Duke-UNCCH Religion & Science Symposium EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Religion and Science are two subjects that heavily impact society. The relationship between the two is often tenuous, but always worth noting. Educational policy in many countries is affected by the perceived conflict between religion and science. Scientific biomedicine and traditional religious medicine interact with each other around the globe. Many students at universities like Duke and UNC grapple with reconciling their faith and their scientific studies. The Duke-UNC Religion and Science Symposium will provide a platform for professors interested in the intersection of the two subjects to present their findings, while also allowing students struggling with the subjects to raise their voices. The symposium aims to promote collaboration between Duke’s Religion department and UNC’s Religious Studies department, while also reaching out to other interdisciplinary departments/institutions at the two schools. It also aims to bring members of both student bodies together for intellectually stimulating discussions. Duke and UNC house America’s top religious studies departments, which puts us in a unique position to tap into the vast knowledge they have with regards to our topic of discussion. Various Duke and UNC faculty, students, and alums have already demonstrated interest in the field, including Dr. Randall Styers (Magic, Religion, and Science; Religion and Secularism), Dr. Ebrahim Moosa (Neurohumanities, Islam), UNC Alumni and Director of NIH Francis Collins. -

Pakistan's Army

Pakistan’s Army: New Chief, traditional institutional interests Introduction A year after speculation about the names of those in the race for selection as the new Army Chief of Pakistan began, General Qamar Bajwa eventually took charge as Pakistan's 16th Chief of Army Staff on 29th of November 2016, succeeding General Raheel Sharif. Ordinarily, such appointments in the defence services of countries do not generate much attention, but the opposite holds true for Pakistan. Why this is so is evident from the popular aphorism, "while every country has an army, the Pakistani Army has a country". In Pakistan, the army has a history of overshadowing political landscape - the democratically elected civilian government in reality has very limited authority or control over critical matters of national importance such as foreign policy and security. A historical background The military in Pakistan is not merely a human resource to guard the country against the enemy but has political wallop and opinions. To know more about the power that the army enjoys in Pakistan, it is necessary to examine the times when Pakistan came into existence in 1947. In 1947, both India and Pakistan were carved out of the British Empire. India became a democracy whereas Pakistan witnessed several military rulers and still continues to suffer from a severe civil- military imbalance even after 70 years of its birth. During India’s war of Independence, the British primarily recruited people from the Northwest of undivided India which post partition became Pakistan. It is noteworthy that the majority of the people recruited in the Pakistan Army during that period were from the Punjab martial races. -

Aitchison College, Mosque

COMMERCIAL CLIENTS INSTALLATIONS OF BREEZAIR COOLING & BRAEMAR HEATING COMMERCIAL & INDUSTRIAL RANGE LAHORE Honda Atlas Cars Pakistan Ltd., Complete Main Plant, Bhai Pheru High Noon Textiles Ltd. Ali Industrial & Tech. Institute (through Packages Ltd.) Izhar Ltd. LUMS, Lahore University of Management Sciences, several buildings. Berger Paints (Pak) Ltd. Jalal Sons Department Stores Mecas Engineering Ltd Sammad Rubber Works Ltd. Ital Sports Ltd. Guard Filters (Pvt) Ltd. Aitchison College, Mosque. Aitchison College, Sports Complex. Aitchison College, All boarding houses. Aitchison College, Junior School Auditorium. Abbassi Corporation Ltd. Arch. Nayyar Ali Dada - Nairang Galleries Arch Zahra Zaka Masood & Sons Big Bird Hatchery Ltd. Big Bird Poultry Ltd. Craftcon Pvt Ltd. Cakes & Bakes - complete main Factory Value TV. Interwood Mobel (Pvt) Ltd. Crystal Engineering Services Dawn Bread, (A. Rahim Foods Ltd.) Beaconhouse School System Eastern Leather Company (Pvt) Ltd. Kims Institute F. W. Fabrication OK Electrical Industries Marhaba Laboratories Ltd. Mallows Department Store Textile Resource Texcom Unicon Consultant ltd. Arch Pervaiz Qureshi. Filmazia TV SAS Cargo Pvt. Ltd Porsche Cars Ltd. University of Central Punjab, Johar Town. Eden Developers, Eden Villas, Multan Road. Mughal Steel, DHA Madeeha’s Beauty Parlour Guard Rice (Pvt) Ltd. Friends Diaries. Future Vision Ltd. Sharaf Logistics (Pak) Ltd. SOLE DISTRIBUTORS - ANSA INTERNATIONAL © Breezair has the Technical depth and strength unmatched by any other company! 1 | P a g e COMMERCIAL CLIENTS LAHORE CONT... Lateef Children Hospital & Polyclinic Construct Architects Ikan Engineering (Pvt) Ltd. Medipak Ltd. Shezan International Ltd. Millac Foods Ltd. Multilynx Ltd. Nee Punhal Fashion Industries. Masood Hospital, Garhi Shahu John Deere Agro Tractors Ltd. Treet Corporation Ltd. -

A Pragmatic Framework for Improving Education in Low-Income Countries Tahir Andrabi

Delivering Education: A Pragmatic Framework for Improving Education in Low-Income Countries Tahir Andrabi (Pomona College, CERP) Jishnu Das (The World Bank, Washington DC and Center for Policy Research, New Delhi) Asim Ijaz Khwaja1 (Harvard University, CERP, BREAD, NBER) Paper prepared for “Handbook of International Education” Abstract Even as primary-school enrollments have increased in most low-income countries, levels of learning remain low and highly unequal. Responding to greater parental demand for quality, low-cost private schools have emerged as one of the fastest growing schooling options, challenging the monopoly of state-provided education and broadening the set of educational providers. Historically, the rise of private schooling is always deeply intertwined with debates around who chooses what schooling is about and who represents the interests of children. We believe that this time is no different. But rather than first resolve the question of how child welfare is to be adjudicated, we argue instead for a `pragmatic framework’. In our pragmatic framework, policy takes into account the full schooling environment—which includes public, private and other types of providers—and is actively concerned with first alleviating constraints that prohibit parents and schools from fulfilling their own stated objectives. Using policy actionable experiments as examples, we show that the pragmatic approach can lead to better schooling for children: Alleviating constraints by providing better information, better access to finance or greater access to skilled teachers brings in more children into school and increases test-scores in language and Mathematics. These areas of improvement are very similar to those where there is already a broad societal consensus that improvement is required. -

Kamil Khan Mumtaz in Pakistan

A Contemporary Architectural Quest and Synthesis: Kamil Khan Mumtaz in Pakistan by Zarminae Ansari Bachelor of Architecture, National College of Arts, Lahore, Pakistan, 1994. Submitted to the Department of Architecture in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 1997 Zarminae Ansari, 1997. All Rights Reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. A uthor ...... ................................................................................. .. Department of Architecture May 9, 1997 Certified by. Attilio Petruccioli Aga Khan Professor of Design for Islamic Culture Thesis Supervisor A ccep ted b y ........................................................................................... Roy Strickland Chairman, Departmental Committee on Graduate Students Department of Architecture JUN 2 0 1997 Room 14-0551 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139 Ph: 617.253.2800 MIT Libraries Email: [email protected] Document Services http://Ilibraries.mit.eduldocs DISCLAIMER OF QUALITY Due to the condition of the original material, there are unavoidable flaws in this reproduction. We have made every effort possible to provide you with the best copy available. If you are dissatisfied with this product and find it unusable, please contact Document Services as soon as possible. Thank you. Some pages in the original document contain color / grayscale pictures or graphics that will not scan or reproduce well. Readers: Ali Asani, (John L. Loeb Associe e Professor of the Humanities, Harvard Univer- sity Faculty of Arts and Sciences). Sibel Bozdogan, (Associate Professor of Architecture, MIT). Hasan-ud-din Khan, (Visiting Associate Professor, AKPIA, MIT). -

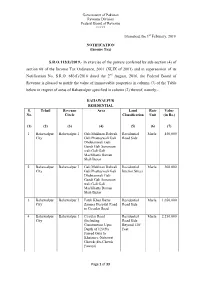

Bahawalpur Specified in Column (2) Thereof, Namely

Government of Pakistan Revenue Division Federal Board of Revenue ***** Islamabad, the 1st February, 2019. NOTIFICATION (Income Tax) S.R.O.112(I)/2019.- In exercise of the powers conferred by sub-section (4) of section 68 of the Income Tax Ordinance, 2001 (XLIX of 2001) and in supersession of its Notification No. S.R.O. 683(I)/2016 dated the 2nd August, 2016, the Federal Board of Revenue is pleased to notify the value of immoveable properties in column (7) of the Table below in respect of areas of Bahawalpur specified in column (2) thereof, namely:- BAHAWALPUR RESIDENTIAL S. Tehsil Revenue Area Land Rate Value No. Circle Classification Unit (in Rs.) (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) 1 Bahawalpur Bahawalpur I Gali Mukhian Dalwali Residential Marla 450,000 City Gali Phattaywali Gali Road Side Dhobianwali Gali Gandi Gali Sonaroon wali Gali Gali Machihatta Daman Shah Bazar 2 Bahawalpur Bahawalpur I Gali Mukhian Dalwali Residential Marla 300,000 City Gali Phattaywali Gali Interior Street Dhobianwali Gali Gandi Gali Sonaroon wali Gali Gali Machihatta Daman Shah Bazar 3 Bahawalpur Bahawalpur I Fateh Khan Bazar Residential Marla 1,050,000 City Zanana Hospital Road Road Side to Circular Road 4 Bahawalpur Bahawalpur I Circular Road Residential Marla 2,250,000 City (Including Road Side Construction Upto Beyond 120' Depth of 120 Ft) Feet Fareed Gate to Khatam-e-Nabowat Chowk (Ex-Chowk Fawara) Page 1 of 33 5 Bahawalpur Bahawalpur I Backside Shops and Residential Marla 1,200,000 City Market Circular Road Plot (Bund Road) Fareed Gate to Ahmad Puri Gate Band Road 6 Bahawalpur Bahawalpur I Khatm-e-Nabowat Residential Marla 1,050,000 City Chowk (Ex-Chowk Plot Fawara) to Millad Chowk (Upto Depth of 100 Feet) Milad Chowk to Sariaki Chowk 7 Bahawalpur Bahawalpur I Millad Chowk to Residential Marla 1,050,000 City General Bus Stand Plot Chowk 8 Bahawalpur Bahawalpur I Band Road Old UC Residential Marla 750,000 City Office to Multani Gate Plot TNT Colony Feel Khana Backside Zoo Talli Mohallah etc. -

Companies Signing

The International Code of Conduct for Private Security Service Providers Signatory Companies Complete List as of 1 August 2013 – Version with Company Details 1. 1Naval One Signed by: Alex Raptis, Operations Manager Date of becoming Signatory Company: 1 May 2013 (by letter) Headquarters: Panama, Panama City Website: www.naval1.com 1Naval One SA., provides specialized professional global security for the maritime industry. Our company offers services that cover the fields of training, consulting and maritime security. Our people are former members of elite and SF units of the armed forces with extensive operational experience in the maritime environment. Naval One S.A., operates to the highest international standards of the industry and in compliance of national and international laws. 2. 2D Security Signed by: Devrim Poyraz, Director Date of becoming Signatory Company: 1 February 2013 (by letter) Headquarters: Turkey, Istanbul Website: www.2d.com.tr We as 2D Security have been operating since 2001 on several different security fields such as ballistics cabin protection and consultancy. With our current company form, now we are entering sea security field. We just hired over 30 special trained navy seals which have employed by the Turkish Navy in the past. These personnel are ready to execute every mission that is needed in sea security. Most of our services will be assisting vessels passing through Suez Canal and Indian Ocean area protecting against piracy. Being part of your family would take us to the next level. One good thing about crew is having different missions in different countries as part of the NATO forces, this means having experience dealing with natives of those countries. -

The Islamia University of Bahawalpur, P a K I S T a N

IUB Scores 100% in HEC Online Classes Dashboard The Islamia University of Bahawalpur, P a k i s t a n Vol. 21 October–December, 2020 Khawaja Ghulam Farid (RA) Seminar and Mehfil-e-Kaafi | 17 Federal Minister for National Food Security Additional IG Police South Punjab Commissioner Bahawalpur Inaugurates Visits IUB Agriculture Farm | 04 Visits IUB | 04 4 New Buses | 09 MD Pakistan Bait ul Mal Visits IUB | 03 Inaugural Ceremony of the Project Punjab Information Technology Board Cut-Flower and Vegetable Production Praises IUB E-Rozgar Center | 07 Research and Training Cell | 13 Honourable Governor Advises IUB to be Student-Centric and Employee-Friendly Engr. Prof. Dr. Athar Mahboob, Vice Chancellor, briefed the Senate meeting of the University. particular, the Governor advised Vice Chancellor, the Islamia Honourable Chancellor about the The Governor appreciated the to University to be more student- University of Bahawalpur made a progress of the Islamia University performance of Islamia University centric and employee-friendly as courtesy call on Governor Punjab of Bahawalpur. Other matters of Bahawalpur and assured of his these ingredients were necessary and Chancellor of the University, discussed included the scheduling wholehearted support to Islamia for world-class universities. Chaudhary Muhammad Sarwar. of upcoming Convocation and University of Bahawalpur. In Governor Punjab Chaudhary Muhammad Sarwar exchanging views with Engr. Prof. Dr. Athar Mahboob, Vice Chancellor National Convention on Peaceful University Campuses Engr. Prof. Dr. Athar Mahboob, Vice Chancellor, the Islamia University of Bahawalpur attended the Vice Chancellor’s Convention on peaceful Universities held in joint collaboration of the Higher Education Commission of Pakistan and Inter University Consortium for Promotion of Social Sciences. -

Military Budgets in India and Pakistan: Trajectories, Priorities, Risks

MILITARY BUDGETS in INDIA and PAKISTAN Trajectories, Priorities, and Risks by Shane Mason Military Budgets in India and Pakistan: Trajectories, Priorities, and Risks © Copyright 2016 by the Stimson Center. All rights reserved. Printed in Washington, D.C. Stimson Center 1211 Connecticut Avenue, NW 8th Floor Washington, D.C. 20036 U.S.A. Visit www.stimson.org for more information about Stimson’s research. 2 Military Budgets in India and Pakistan: Trajectories, Priorities, and Risks PREFACE The Stimson Center prides itself in fact-driven analysis, as exemplified in Shane Mason’s report, Military Budgets in India and Pakistan: Trajectories, Priorities, and Risks. Shane’s analysis and policy-relevant conclusions are properly caveated, because India does not reveal some important data about defense spending, and Pakistan, while doing better to offer its citizens defense budget information, still reveals less than India. While Shane has found it necessary to draw inferences about spending for nuclear weapon- related programs, for which there is little publicly available information, he has been transparent about his sources and methodology. Those who appreciate reading the pages of The Economist will find comfort immersing themselves in Shane’s charts and graphs comparing trends in Indian and Pakistani defense expenditures. This Stimson report is also accessible to those who prefer analysis to numerology. Shane’s analytical bottom lines are worth highlighting. The growth of India’s defense expenditures relative to Pakistan are noteworthy, but the full impact of this differential will be diminished absent reforms in familiar organizational, bureaucratic, and procurement practices, as well as by growth in benefit payments.