Yorke Peninsula

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Camping on Yorke Peninsula Information Sheet

brought to you by the award winning www.visityorkepeninsula.com.au OPEN 7 DAYS A WEEK 1800 202 445 PURCHASE YOUR PERMIT … online at www.visityorkepeninsula.com.au/camping/purchase-a-permit in person or by phone at Yorke Peninsula Visitor Centre in Minlaton or at any of Council’s offices located in Maitland, Minlaton, Yorketown or Warooka 1 - THE GAP 2 - THE BAMBOOS 3-TIPARRA ROCKS 19 - PARARA 4 - WAURALTEE BEACH 5 - BARKER ROCKS 6 - PORT MINLACOWIE 7 - LEN BARKER 8 - BURNERS BEACH 9 - GRAVEL BAY RESERVE 10 - SWINCER ROCKS 11 - GLEESONS LANDING 12 - DALY HEAD 16 - MOZZIE 18 - WATTLE POINT 15 - STURT FLAT BAY 17 - GOLDSMITH BEACH 14 - FOUL BAY 13 - FOUL BAY BOAT RAMP for further information and assistance call Yorke Peninsula Visitor Centre on 1800 202 445 please have your vehicle and caravan / trailer registration on hand when calling permit full price ratepayers price nightly $10.00 $10.00 weekly $50.00 $25.00 monthly $150.00 $75.00 yearly $500.00 $250.00 (Discount is available on provision of YPC rate assessment number) When camping at any of Yorke Peninsula Council’s bush camp grounds, you will need to bring your own water and firewood; gas or fuel stoves are preferred. It is your responsibility to familiarise yourself with any fire bans in place. Dogs kept under control or on a lead are welcome. 1. The Gap: 34°14'06.5"S 137°30'06.6"E on the north west coast of the peninsula, 15 kilometres north of Balgowan - access from Spencer Highway just south of Weetulta or along coastal track from Balgowan - beach launching -– toilet facilities available - good beach for kids – beach fishing for tommies and gar – no shade 2. -

Marine Biodiversity of the Northern and Yorke Peninsula NRM Region

Marine Environment and Ecology Benthic Ecology Subprogram Marine Biodiversity of the Northern and Yorke Peninsula NRM Region SARDI Publication No. F2009/000531-1 SARDI Research Report series No. 415 Keith Rowling, Shirley Sorokin, Leonardo Mantilla and David Currie SARDI Aquatic Sciences PO Box 120 Henley Beach SA 5022 December 2009 Prepared for the Department for Environment and Heritage 1 Marine Biodiversity of the Northern and Yorke Peninsula NRM Region Keith Rowling, Shirley Sorokin, Leonardo Mantilla and David Currie December 2009 SARDI Publication No. F2009/000531-1 SARDI Research Report Series No. 415 Prepared for the Department for Environment and Heritage 2 This Publication may be cited as: Rowling, K.P., Sorokin, S.J., Mantilla, L. & Currie, D.R. (2009) Marine Biodiversity of the Northern and Yorke Peninsula NRM Region. South Australian Research and Development Institute (Aquatic Sciences), Adelaide. SARDI Publication No. F2009/000531-1. South Australian Research and Development Institute SARDI Aquatic Sciences 2 Hamra Avenue West Beach SA 5024 Telephone: (08) 8207 5400 Facsimile: (08) 8207 5406 http://www.sardi.sa.gov.au DISCLAIMER The authors warrant that they have taken all reasonable care in producing this report. The report has been through the SARDI internal review process, and has been formally approved for release by the Chief of Division. Although all reasonable efforts have been made to ensure quality, SARDI does not warrant that the information in this report is free from errors or omissions. SARDI does not accept any liability for the contents of this report or for any consequences arising from its use or any reliance placed upon it. -

**YP 6Folds.Wrecks

YORKE PENINSULA Fisherman Bay Redhill Yorke Peninsula Shipwrecks Fisherman Shag Island Bay Munderoo Bay Port Broughton Mundoora Webling Colinsfield "The vessel [Hougomont] was overtaken in the Great Australian Bight by a vast Point Lake View 8 black cloud bank that unleashed cyclonic winds of up to 100 miles an hour. After 2 8 2 Wokurna 3 For further information she had spent nearly 12 hours fighting the storm, all that was left of her top- Bews 1 Tickera Bay Yorke Peninsula Regional Visitor Information Centre Snowtown hamper were the stumps of her foremast, mizzenmast and lower jigger mast." Tickera 50 Moonta Road Barunga Gap Myponie Brucefield Alford Point Black Rock Corner 25 Kadina SA 5554 9 Bute Point 2 During 1802 and 1803, the European explorers, Matthew Flinders and Nicholas Baudin charted the coastline of Riley 37 Ph 1800 654 991 North Beach Wallaroo 9 1 Willamulka Yorke Peninsula and their skill and accuracy in defining the coastline meant their charts were used well into the Wallaroo 9 2 Bay 3 Wallaroo Bird Islands Mines Kadina Ninnes 20th century. From the 1840s through to the 1940s ships of various types and sizes were the major means of Conservation Park Plains 20 Harvest Corner Visitor Information Centre 6 7 1 1 transport of cargo and people to and from Yorke Peninsula. It is not surprising then to find a total of 85 Moonta Bay 29 Main Street 13 Paskeville Moonta Bay Kulpara 0 shipwrecks scattered around its coastline. Explore the coastline of Yorke Peninsula and discover for yourself the Moonta 1 15 Port Hughes Cunliffe 2 Minlaton SA 5575 0 Moonta Mines Melton Tiparra Cocoanut Bay 3 remains of the many wrecks in this region. -

S P E N C E R G U L F S T G U L F V I N C E N T Adelaide

Yatala Harbour Paratoo Hill Turkey 1640 Sunset Hill Pekina Hill Mt Grainger Nackara Hill 1296 Katunga Booleroo "Avonlea" 2297 Depot Hill Creek 2133 Wilcherry Hill 975 Roopena 1844 Grampus Hill Anabama East Hut 1001 Dawson 1182 660 Mt Remarkable SOUTH Mount 2169 440 660 (salt) Mt Robert Grainger Scobie Hill "Mazar" vermin 3160 2264 "Manunda" Wirrigenda Hill Weednanna Hill Mt Whyalla Melrose Black Rock Goldfield 827 "Buckleboo" 893 729 Mambray Creek 2133 "Wyoming" salt (2658±) RANGE Pekina Wheal Bassett Mine 1001 765 Station Hill Creek Manunda 1073 proof 1477 Cooyerdoo Hill Maurice Hill 2566 Morowie Hill Nackara (abandoned) "Bulyninnie" "Oak Park" "Kimberley" "Wilcherry" LAKE "Budgeree" fence GILLES Booleroo Oratan Rock 417 Yeltanna Hill Centre Oodla "Hill Grange" Plain 1431 "Gilles Downs" Wirra Hillgrange 1073 B pipeline "Wattle Grove" O Tcharkuldu Hill T Fullerville "Tiverton 942 E HWY Outstation" N Backy Pt "Old Manunda" 276 E pumping station L substation Tregalana Baroota Yatina L Fitzgerald Bay A Middleback Murray Town 2097 water Ucolta "Pitcairn" E Buckleboo 1306 G 315 water AN Wild Dog Hill salt Tarcowie R Iron Peak "Terrananya" Cunyarie Moseley Nobs "Middleback" 1900 works (1900±) 1234 "Lilydale" H False Bay substation Yaninee I Stoney Hill O L PETERBOROUGH "Blue Hills" LC L HWY Point Lowly PEKINA A 378 S Iron Prince Mine Black Pt Lancelot RANGE (2294±) 1228 PU 499 Corrobinnie Hill 965 Iron Baron "Oakvale" Wudinna Hill 689 Cortlinye "Kimboo" Iron Baron Waite Hill "Loch Lilly" 857 "Pualco" pipeline Mt Nadjuri 499 Pinbong 1244 Iron -

15.2 Sand Islands and Shoals

15 Islands 15.2 Sand Islands and Shoals Figure 15.1: (A) Aerial view of Troubridge Island and surrounding Troubridge Shoals: (c) Coastal Protection Branch, DEWNR. (B). Troubridge Island: (c) W. Bonham, Lighthouses of Australia. Asset Sand Islands and Shoals Description A crest of sand which rises above water level from a broad marine sand bank, forming an unstable sand island - Troubridge Island - which changes shape and size over time. The island is about 5m high at high tide, and about 2 hectares in area when inundated, but considerable larger at low tide. The island is surrounded by shallow sand embankments (Troubridge Shoals). Examples of Key Little Penguin, Black-faced Cormorant, Crested Tern and other breeding sea Species birds (numerous species) migratory wading birds (numerous species) abundant sand-dwelling invertebrates - food sources for fish and wading birds Pink Snapper King George whiting and school whiting syngnathid fishes (e.g. seahorses, pipefishes) sponges (forming “sponge gardens”, on consolidated sand) cowries; volutes and other specimen shells Knobby Argonaut (‘paper nautilus’ octopus) giant spider crab southern calamari Main Location Troubridge Island (and shallow sandbanks to the west - Troubridge Shoals) Notes Troubridge Island Conservation Park (approx. 260 hectares) was declared in 1982, and extended in 1986, partly to protect major breeding colonies of several seabird species, and provide protection for an important feeding ground used by migratory wading birds, listed under international treaties. Oceanography At the bottom of Gulf St Vincent, off the eastern “heel” of Yorke Peninsula, waters less than 20m occur up to 10km from shore. The oceanographic conditions have led to a long-term build-up of sand in some areas, including the creation of Troubridge Island, a sand island about 7km east of Sultana Point. -

NY NRM Levy Study

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Full document available at www.marineparks.sa.gov.au Lower Yorke Peninsula Marine Park Regional Impact Statement A report prepared for Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources Prepared by e c o n s e a r c h In association with the Australian Workplace Innovation and Social Research Centre, Dr Hugh Kirkman, Dr Simon Bryars and James Brook 2 August 2012 EconSearch Pty Ltd 214 Kensington Road Marryatville SA 5068 Tel: (08) 8431 5533 Fax: (08) 8431 7710 www.econsearch.com.au DEWNR Lower Yorke Peninsula Marine Park Regional Impact Statement Executive Summary Situated in the Gulf St Vincent Bioregion, the Lower Yorke Peninsula Marine Park is located around the heel of Yorke Peninsula, from Point Davenport Conservation Park to near Stansbury, and includes Troubridge Island. Impacts of implementing the draft management plans were assessed against a base case scenario of no management plans. The base case is not static, and requires an understanding of the existing trends in natural resource, economic and social conditions. There are external factors which influence both the ‘with management plan’ and the base case scenarios that were taken into consideration. Marine Park Profile The eastern coastline of the park is dominated by limestone cliff slopes and includes mostly sheltered, low rocky shores, bays and some sandy beaches. Linked offshore are large areas of low profile platform reef interspersed with sandy seafloor and seagrass. Particular features include the high current shoal grounds adjacent to Edithburgh, and the unique mobile sand spit of Troubridge Island. The southern coast bays contain large areas of seagrass scattered with sandy seafloor patches. -

Marine Park 12 Southern Spencer Gulf Marine Park

Marine Park 12 12 Southern Spencer Gulf Marine Park Park at a glance Boundary description Southern Spencer Gulf Marine Park is located between The Southern Spencer Gulf Marine Park comprises the the foot of Yorke Peninsula and the central north coast area bounded by a line commencing on the coastline at of Kangaroo Island. median high water at a point 137°11’25.4”E, 35°13’44.65”S At 2,972 km2, it represents 11% of South Australia’s (at or about Point Yorke), then running progressively: marine parks network. ○ southerly along the geodesic to its intersection with Community and industry the coastline of Kangaroo Island at median high water at a point 137°11’25.4”E, 35°37’23.25”S; • The Narungga Aboriginal people have traditional associations with the region. ○ westerly along the coastline of Kangaroo Island at median high water (inclusive of all bays, lagoons • Commercial fishers target abalone, rock lobster, shark, and headlands) to a point 136°46’52.75”E, 35°42’6.8”S pilchards, prawns, snapper, King George whiting (in the vicinity of Cape Forbin); and other scalefish species. ○ northerly along the geodesic to a point 136°46’52.75”E, • Fishing, boating, sailing, diving, snorkelling, swimming, 34°48’31.99”S; camping and beach walking are popular. ○ easterly along the geodesic to its intersection with the • Also featured in this marine park are the Investigator coastline at median high water at a point 137°27’34.71”E, Strait Maritime Heritage Trail and other historical sites 34°48’31.99”S; and listed on the Register of the National Estate. -

Wool Statistical Area's

Wool Statistical Area's Monday, 24 May, 2010 A ALBURY WEST 2640 N28 ANAMA 5464 S15 ARDEN VALE 5433 S05 ABBETON PARK 5417 S15 ALDAVILLA 2440 N42 ANCONA 3715 V14 ARDGLEN 2338 N20 ABBEY 6280 W18 ALDERSGATE 5070 S18 ANDAMOOKA OPALFIELDS5722 S04 ARDING 2358 N03 ABBOTSFORD 2046 N21 ALDERSYDE 6306 W11 ANDAMOOKA STATION 5720 S04 ARDINGLY 6630 W06 ABBOTSFORD 3067 V30 ALDGATE 5154 S18 ANDAS PARK 5353 S19 ARDJORIE STATION 6728 W01 ABBOTSFORD POINT 2046 N21 ALDGATE NORTH 5154 S18 ANDERSON 3995 V31 ARDLETHAN 2665 N29 ABBOTSHAM 7315 T02 ALDGATE PARK 5154 S18 ANDO 2631 N24 ARDMONA 3629 V09 ABERCROMBIE 2795 N19 ALDINGA 5173 S18 ANDOVER 7120 T05 ARDNO 3312 V20 ABERCROMBIE CAVES 2795 N19 ALDINGA BEACH 5173 S18 ANDREWS 5454 S09 ARDONACHIE 3286 V24 ABERDEEN 5417 S15 ALECTOWN 2870 N15 ANEMBO 2621 N24 ARDROSS 6153 W15 ABERDEEN 7310 T02 ALEXANDER PARK 5039 S18 ANGAS PLAINS 5255 S20 ARDROSSAN 5571 S17 ABERFELDY 3825 V33 ALEXANDRA 3714 V14 ANGAS VALLEY 5238 S25 AREEGRA 3480 V02 ABERFOYLE 2350 N03 ALEXANDRA BRIDGE 6288 W18 ANGASTON 5353 S19 ARGALONG 2720 N27 ABERFOYLE PARK 5159 S18 ALEXANDRA HILLS 4161 Q30 ANGEPENA 5732 S05 ARGENTON 2284 N20 ABINGA 5710 18 ALFORD 5554 S16 ANGIP 3393 V02 ARGENTS HILL 2449 N01 ABROLHOS ISLANDS 6532 W06 ALFORDS POINT 2234 N21 ANGLE PARK 5010 S18 ARGYLE 2852 N17 ABYDOS 6721 W02 ALFRED COVE 6154 W15 ANGLE VALE 5117 S18 ARGYLE 3523 V15 ACACIA CREEK 2476 N02 ALFRED TOWN 2650 N29 ANGLEDALE 2550 N43 ARGYLE 6239 W17 ACACIA PLATEAU 2476 N02 ALFREDTON 3350 V26 ANGLEDOOL 2832 N12 ARGYLE DOWNS STATION6743 W01 ACACIA RIDGE 4110 Q30 ALGEBUCKINA -

Yorke Peninsula Council Rural Roads Rack Plan

.! .! .! .! ! . !. !. !. !. .! !. !. .! ! . !. !. ! . !. !. !. ! . ! . ! . .! !. !. !. ! ! . ! . ! . ! . ! . ! RACK PLAN 953 CO . ! PPE . ! R COAS Yorke Peninsula Council HIG T HWAY !. !. K Y O . ! D ! C . E O G N D A AILWAY O R R T R !. W E A D D O H C E COCONUT R O CE R . TERRA ! G R . O ! A A E R I Rural Roads R E A N B R O R N O Y O E . ROAD ! N E R D T . ! D R R A D N RO O A HOLMA S . .! ! C O N P R ! . This plan reflects the Rural & State road names & road A L A E S . DLER ROAD ! B A C . PE ! B IN N A U R A L SS S W E R D D E I A C D N A O D . ! S R T D IR B O A C O . O A R ! H A H extents approved by the Yorke Peninsula Council U O G T O O P O T P D P !. O A R . R E ! O D M A . R ! A D P R A A D O PORT ARTHUR 5572 H O AD S R .! E O R OAD R R D NG E I . NA ! PE MSH LA R N G R ! . CKEY ROAD STU S N L O (Section 219 Local Government Act) C H Y U D .! C L M D C O A R W A . L ! O E IL K H D .! U A YS D E . ! L O EL V O K A A . -

Northern and Yorke Coastal Management Action Plan 2019

NORTHERN AND YORKE COASTAL MANAGEMENT ACTION PLAN 2019 DRAFT FOR PUBLIC CONSULTATION 1 January 2020 The authors of this Plan acknowledge the Traditional Custodians of the land which is described herein, and pay our respects to their Elders past, present and emerging. We honour the deep continuing connection Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples share with Country, and give respect to the Nukunu, Narungga and Kaurna people. We would also like to thank all community members, traditional owners and individuals who took the time to come to meetings or provided valuable input over the phone. Professional Acknowledgements: Andy Sharp (1), Max Barr (1), Simon Millcock (2), Brian Hales (2), Sharie Detmar (3), Caroline Taylor (4), Fabienne Dee (5), Deni Russell (5), Kate Pearce (5), Kane Smith (5), Stephen Goldsworthy (6), Deborah Furbank (6), Doug Fotheringham (7), Doug Riley (7), Adrian Shackley (7), Ron Sandercock (7), Anita Crisp (8), Jeff Groves (9), Andrew Black (9), Matt Turner (10). 1. Department for Environment and Water (also project Steering Group and Technical Review Panel) 2. Legatus Group 3. Department for Environment and Water Coast Management Branch 4. Natural Resources Adelaide and Mt Lofty Ranges 5. Department for Environment and Water (regional staff) 6. Yorke Peninsula Council 7. Individuals providing invaluable technical knowledge and expertise 8. Upper Spencer Gulf Councils, SA Coastal Councils Alliance 9. Birds SA 10. Department for Environment and Water (Aboriginal Partnerships Officer) The Northern and Yorke Natural Resources Management (NRM) Board allocated funding to progress this study and Natural Resources Northern and Yorke (NRNY) allocated staff time and resources to support it. -

Coastal Landscapes of South Australia

Welcome to the electronic edition of Coastal Landscapes of South Australia. The book opens with the bookmark panel and you will see the contents page. Click on this anytime to return to the contents. You can also add your own bookmarks. Each chapter heading in the contents table is clickable and will take you direct to the chapter. Return using the contents link in the bookmarks. The whole document is fully searchable. Enjoy. Coastal Landscapes of South Australia This book is available as a free fully-searchable ebook from www.adelaide.edu.au/press Published in Adelaide by University of Adelaide Press Barr Smith Library, Level 3.5 The University of Adelaide South Australia 5005 [email protected] www.adelaide.edu.au/press The University of Adelaide Press publishes peer reviewed scholarly books. It aims to maximise access to the best research by publishing works through the internet as free downloads and for sale as high quality printed volumes. © 2016 Robert P. Bourman, Colin V. Murray-Wallace and Nick Harvey This work is licenced under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) License. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. This licence allows for the copying, distribution, display and performance of this work for non-commercial purposes providing the work is clearly attributed to the copyright holders. Address all inquiries to the Director at the above address. -

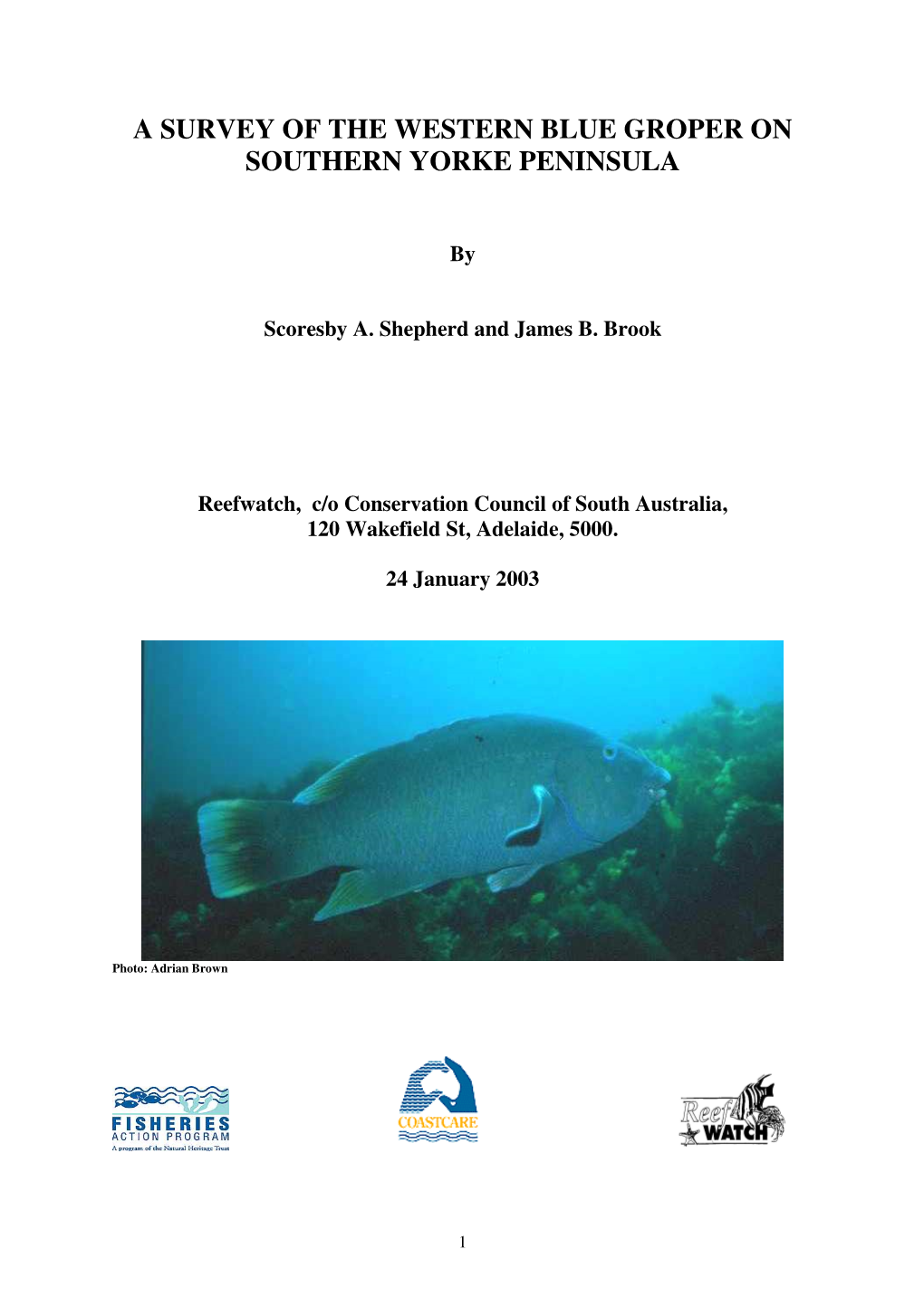

Chapter 9: Northern and Yorke Regional Oiled Wildlife Response

9. NORTHERN AND YORKE REGIONAL OILED WILDLIFE RESPONSE PLAN Chapter 9 – Northern and Yorke regional plan 130 History of this Document This regional plan was developed by the Department for Environment and Water (DEW) and the Australian Marine Oil Spill Centre (AMOSC) to be consistent with the Western Australia (WA) Pilbara Regional Oiled Wildlife Response Plan which was produced jointly by the Western Australia Department of Parks and Wildlife (Parks and Wildlife) and AMOSC on behalf of the Petroleum Industry to set out the minimum standard for an OWR in state waters. The South Australian Oiled Wildlife Response Plan contains the general arrangements which apply across the state and seven chapters which comprise the local plans for each of the coastal regions. This chapter describe those local arrangements in the Northern and Yorke Peninsula Region. The Northern and Yorke Peninsula Regional Oiled Wildlife Response Plan was developed in consultation with Northern and Yorke Peninsula regional staff. The contribution and assistance of AMOSC and the Western Australian Government is both acknowledged and appreciated. The Plan was approved by the Northern and Yorke Peninsula Regional Director and adopted on 5 November 2018. Exercise and Review periods Exercising This plan will be exercised at least annually in accordance with South Australian Marine Oil Pollution Plans and petroleum titleholder oil pollution emergency plans, as required. Review This plan will be reviewed and updated by the Director, Northern and Yorke Peninsula, DEW and AMOSC initially within twelve months of release. Thereafter it will be reviewed following an incident or at least once every two years.