Ten-Point Peace Plan for Northern Ireland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thatcher, Northern Ireland and Anglo-Irish Relations, 1979-1990

From ‘as British as Finchley’ to ‘no selfish strategic interest’: Thatcher, Northern Ireland and Anglo-Irish Relations, 1979-1990 Fiona Diane McKelvey, BA (Hons), MRes Faculty of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences of Ulster University A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Ulster University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2018 I confirm that the word count of this thesis is less than 100,000 words excluding the title page, contents, acknowledgements, summary or abstract, abbreviations, footnotes, diagrams, maps, illustrations, tables, appendices, and references or bibliography Contents Acknowledgements i Abstract ii Abbreviations iii List of Tables v Introduction An Unrequited Love Affair? Unionism and Conservatism, 1885-1979 1 Research Questions, Contribution to Knowledge, Research Methods, Methodology and Structure of Thesis 1 Playing the Orange Card: Westminster and the Home Rule Crises, 1885-1921 10 The Realm of ‘old unhappy far-off things and battles long ago’: Ulster Unionists at Westminster after 1921 18 ‘For God's sake bring me a large Scotch. What a bloody awful country’: 1950-1974 22 Thatcher on the Road to Number Ten, 1975-1979 26 Conclusion 28 Chapter 1 Jack Lynch, Charles J. Haughey and Margaret Thatcher, 1979-1981 31 'Rise and Follow Charlie': Haughey's Journey from the Backbenches to the Taoiseach's Office 34 The Atkins Talks 40 Haughey’s Search for the ‘glittering prize’ 45 The Haughey-Thatcher Meetings 49 Conclusion 65 Chapter 2 Crisis in Ireland: The Hunger Strikes, 1980-1981 -

Full Book PDF Download

9780719075636_1_pre.qxd 17/2/09 2:11 PM Page i Irish literature since 1990 9780719075636_1_pre.qxd 17/2/09 2:11 PM Page ii 9780719075636_1_pre.qxd 17/2/09 2:11 PM Page iii Irish literature since 1990 Diverse voices edited by Scott Brewster and Michael Parker Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed in the United States exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan 9780719075636_1_pre.qxd 17/2/09 2:11 PM Page iv Copyright © Manchester University Press 2009 While copyright in the volume as a whole is vested in Manchester University Press, copyright in individual chapters belongs to their respective authors. This electronic version has been made freely available under a Creative Commons (CC-BY- NC-ND) licence, which permits non-commercial use, distribution and reproduction provided the author(s) and Manchester University Press are fully cited and no modifications or adaptations are made. Details of the licence can be viewed at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Published by Manchester University Press Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 978 07190 7563 6 hardback First published 2009 18171615141312111009 10987654321 Typeset by Graphicraft Limited, Hong Kong 9780719075636_1_pre.qxd 17/2/09 2:11 PM Page v Contents Acknowledgements page vii Notes -

Aguisíní Appendices Aguisín 1: Comóradh Céad Bliain Ollscoil Na Héireann Appendix 1: Centenary of the National University of Ireland

Aguisíní Appendices Aguisín 1: Comóradh Céad Bliain Ollscoil na hÉireann Appendix 1: Centenary of the National University of Ireland Píosa reachtaíochta stairiúil ab ea Acht Ollscoileanna na hÉireann, 1908, a chuir deireadh go foirmeálta le tréimhse shuaite in oideachas tríú leibhéal na hEireann agus a d’oscail caibidil nua agus nuálaíoch: a bhunaigh dhá ollscoil ar leith – ceann amháin díobh i mBéal Feirste, in ionad sean-Choláiste na Ríona den Ollscoil Ríoga, agus an ceann eile lárnaithe i mBaile Átha Cliath, ollscoil fheidearálach ina raibh coláistí na hOllscoile Ríoga de Bhaile Átha Cliath, Corcaigh agus Gaillimh, athchumtha mar Chomh-Choláistí d’Ollscoil nua na hÉirean,. Sa bhliain 2008, rinne OÉ ceiliúradh ar chéad bliain ar an saol. Is iomaí athrú suntasach a a tharla thar na mblianta, go háiriithe nuair a ritheadh Acht na nOllscoileanna i 1997, a rinneadh na Comh-Choláistí i mBaile Átha Cliath, Corcaigh agus Gaillimh a athbhunú mar Chomh-Ollscoileanna, agus a rinneadh an Coláiste Aitheanta (Coláiste Phádraig, Má Nuad) a athstruchtúrú mar Ollscoil na hÉireann, Má Nuad – Comh-Ollscoil nua. Cuireadh tús le comóradh an chéid ar an 3 Nollaig 2007 agus chríochnaigh an ceiliúradh le mórchomhdháil agus bronnadh céime speisialta ar an 3 Nollaig 2008. Comóradh céad bliain ón gcéad chruinniú de Sheanad OÉ ar an lá céanna a nochtaíodh protráid den Seansailéirm, an Dr. Garret FitzGerald. Tá liosta de na hócáidí ar fad thíos. The Irish Universities Act 1908 was a historic piece of legislation, formally closing a turbulent chapter in Irish third level education and opening a new and innovational chapter: establishing two separate universities, one in Belfast, replacing the old Queen’s College of the Royal University, the other with its seat in Dublin, a federal university comprising the Royal University colleges of Dublin, Cork and Galway, re-structured as Constituent Colleges of the new National University of Ireland. -

2012 Biennial Conference Layout 1

Biennial Delegate Conference | 2012 City Hotel, Derry 17th‐18th April 2012 Membership of the Northern Ireland Committee 2010‐12 Membership Chairperson Ms A Hall‐Callaghan UTU Vice‐Chairperson Ms P Dooley UNISON Members K Smyth INTO* E McCann Derry Trades Council** Ms P Dooley UNISON J Pollock UNITE L Huston CWU M Langhammer ATL B Lawn PCS E Coy GMB E McGlone UNITE Ms P McKeown UNISON K McKinney SIPTU Ms M Morgan NIPSA S Searson NASUWT K Smyth USDAW T Trainor UNITE G Hanna IBOA B Campfield NIPSA Ex‐Officio J O’Connor President ICTU (July 09 to 2011) E McGlone President ICTU (July 11 to 2013) D Begg General Secretary ICTU P Bunting Asst. General Secretary *From February 2012, K Smyth was substituted by G Murphy **From March 2011 Mr McCann was substituted, by Mr L Gallagher. Attendance At Meetings At the time of preparing this report 20 meetings were held during the 2010‐12 period. The following is the attendance record of the NIC members: L Huston 14 K McKinney 13 B Campfield 18 M Langhammer 14 M Morgan 17 E McCann 7 L Gallagher 6 S Searson 18 P Dooley 17 B Lawn 16 Kieran Smyth 19 J Pollock 14 E McGlone 17 T Trainor 17 A Hall‐Callaghan 17 P McKeown 16 Kevin Smyth 15 G Murphy 2 G Hanna 13 E Coy 13 3 Thompsons are proud to work with trade unions and have worked to promote social justice since 1921. For more information about Thompsons please call 028 9089 0400 or visit www.thompsonsmcclure.com Regulated by the Law Society of Northern Ireland March for the Alternative image © Rod Leon Contents Contents SECTION TITLE PAGE A INTRODUCTION 7 B CONFERENCE RESOLUTIONS 11 C TRADE UNION ORGANISATION 15 D TRADE UNION EDUCATION, TRAINING 29 AND LIFELONG LEARNING E POLITICAL & ECONOMIC REPORT 35 F MIGRANT WORKERS 91 G EQUALITY & HUMAN RIGHTS 101 H INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS & EMPLOYMENT RIGHTS 125 I HEALTH AND SAFETY 139 APPENDIX TITLE PAGE 1 List of Submissions 143 5 Who we Are • OCN NI is the leading credit based Awarding Organisation in Northern Ireland, providing learning accreditation in Northern Ireland since 1995. -

Building Government Institutions in Northern Ireland—Strand One Negotiations

BUILDING GOVERNMENT INSTITUTIONS IN NORTHERN IRELAND —STRAND ONE NEGOTIATIONS Deaglán de Bréadún —IMPLEMENTING STRAND ONE Steven King IBIS working paper no. 11 BUILDING GOVERNMENT INSTITUTIONS IN NORTHERN IRELAND —STRAND ONE NEGOTIATIONS Deaglán de Bréadún —IMPLEMENTING STRAND ONE Steven King No. 1 in the lecture series “Institution building and the peace process: the challenge of implementation” organised in association with the Conference of University Rectors in Ireland Working Papers in British-Irish Studies No. 11, 2001 Institute for British-Irish Studies University College Dublin Working Papers in British-Irish Studies No. 11, 2001 © the authors, 2001 ISSN 1649-0304 ABSTRACTS BUILDING GOVERNMENT INSTITUTIONS IN NORTHERN IRELAND —STRAND ONE NEGOTIATIONS The Good Friday Agreement was the culmination of almost two years of multi-party negotiations designed to resolve difficult relationships between the two main com- munities within Northern Ireland, between North and South and between Ireland and Great Britain. The three-stranded approach had already been in use for some time as a format for discussion. The multi-party negotiations in 1997-98 secured Sinn Féin’s reluctant acceptance of a Northern Ireland Assembly, which the party had earlier rejected, as a quid pro quo for significant North-South bodies. Despite the traditional nationalist and republican slogan of “No return to Stormont”, in the negotiations the nationalists needed as much devolution of power as possible if their ministers were to meet counterparts from the Republic on more or less equal terms on the proposed North-South Ministerial Council. Notwithstanding historic tensions between constitutional nationalists and republicans, the SDLP’s success in negotiating a cabinet-style executive, rather than the loose committee structure favoured by unionists, helped ensure there would be a substantial North-South Min- isterial Council, as sought by both wings of nationalism. -

Dáil Éireann

DÁIL ÉIREANN AN COISTE UM CHUNTAIS PHOIBLÍ COMMITTEE OF PUBLIC ACCOUNTS Déardaoin, 7 Samhain 2013 Thursday, 7 November 2013 The Committee met at 10.00 a.m. MEMBERS PRESENT: Deputy John Deasy, Deputy Eoghan Murphy, Deputy Sean Fleming, Deputy Derek Nolan, Deputy Simon Harris, Deputy Kieran O’Donnell, Deputy Mary Lou McDonald, Deputy Shane Ross. DEPUTY JOHN MCGUINNESS IN THE CHAIR. 1 BUSINESS OF COMMITTEE Mr. Seamus McCarthy (An tArd Reachtaire Cuntas agus Ciste) called and examined. Business of Committee Chairman: Are the minutes of the meeting of 24 October 2013 agreed to? Agreed. We have received correspondence since our meeting on Thursday, 24 October. No. 3A.1 is correspondence, dated 24 October 2013, from Mr. Colin Bray, chief executive officer, Ordnance Survey Ireland, providing additional information requested by the committee at its meeting on 17 October. This correspondence is to be noted and published, with the exception of the details of the lease for Tuam and Sligo. One issue that needs to be followed up on is the payment of board director fees, irrespective of whether board members attend meetings. We will include this matter in an upcoming report. No. 3B.1 is correspondence, dated 6 September 2013, from Mr. John Moriarty on the Na- tional Aquatic Centre. The correspondence is to be noted. The evidence given to the committee on the contracts entered into by Campus and Stadium Ireland was subsequently corrected and, therefore, no further issues arise. No. 3B.2 is correspondence, dated 10 October 2013, from an anonymous source regarding St. Catherine’s special needs school, County Wicklow. -

Statement on the Ethiopia-Eritrea Final Peace Agreement Remarks To

Administration of William J. Clinton, 2000 / Dec. 12 economic opportunity in Ireland and the out- third time I did that, to put it charitably, I reach and impact you’re having beyond the bor- thought I had lost my mind. [Laughter] But ders of your nation, is also a part of the peace I can tell you that every effort has been an process, because you have shown the benefits honor. I believe America has in some tiny way of an open, competitive, peaceful society. repaid this nation and its people for the massive And nobody wants to go back to the Troubles. gifts of your people you have given to us over There are a few hills we still have to climb, so many years, going back to our beginnings. and we’ll figure out how to do that, and I hope I hope that is true. that our trip here is of some help toward that For me, one of the things I will most cherish end. But as long as the people here, as free about the 8 years the American people were citizens of this great democracy, and as long good enough to let me serve as President is as their allies and friends in the North increas- that I had a chance to put America on the ingly follow the same path of creating opportuni- side of peace and dignity and equality and op- ties that bring people together instead of argu- portunity for all the people in both communities ments that drive people apart, then the political in Northern Ireland, and for a reconciliation be- systems will follow the people. -

The Implications of Brexit for Civil Society and the Peace Process

The Implications of Brexit for Civil Society and the Peace Process Distinguished guests and colleagues, Like many of the Members of the European Economic and Social Committee who are here today, I am not a native English speaker. But there is one word that I have added to my English vocabulary in recent months: 'backstop'! The definition of the word 'backstop' is quite technical. But the symbolism that it has taken on since the Brexit negotiations began, is truly profound. I would not be surprised if in the future, dictionaries add a new meaning directly linking the word to the Brexit negotiations! As a German from Berlin, I fully understand both the symbolism and the impact of physical barriers and walls. I understand the need to look forward instead of backwards and how this shapes our identity. As a European, I am convinced that our most valued assets are Peace, Democracy and Partnership. And although not everyone here agrees on what the impact of Brexit will be on the Island of Ireland, there is no doubt that all of us, the other 27 EU Member States, European civil society and the European Institutions, will do everything in our means to ensure that the spirit of cooperation enshrined in the Good Friday Agreement, continues in your minds and in your daily lives. It is for this reason that we, civil society from the 28 EU Member States, are here today in Belfast. We are here to listen to your concerns, your fears and your hopes. We are here to reach out a hand to civil society on both sides of the border. -

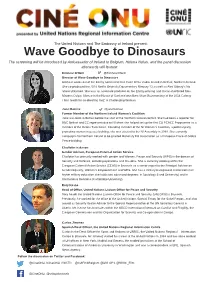

Wave Goodbye to Dinosaurs

The United Nations and The Embassy of Ireland present: Wave Goodbye to Dinosaurs The screening will be introduced by Ambassador of Ireland to Belgium, Helena Nolan, and the panel discussion afterwards will feature: Eimhear O'Neill @EimhearONeill Director of Wave Goodbye to Dinosaurs Eimhear works out of the Emmy nominated Fine Point Films studio, based in Belfast, Northern Ireland. She co-produced the 2018 Netflix Originals Documentary Mercury 13 as well as Alex Gibney’s No Stone Unturned. She was an associate producer on the Emmy-winning and Oscar-shortlisted Mea Maxima Culpa: Silence in the House of God and won Best Short Documentary at the 2014 Galway Film Fleadh for co-directing Inez: A Challenging Woman. Jane Morrice @janemorrice Former Member of the Northern Ireland Women's Coalition Jane was born in Belfast before the start of the Northern Ireland conflict. She had been a reporter for BBC Belfast and EC representative to NI when she helped set up the first EU PEACE Programme as a member of the Delors Task Force. Founding member of the NI Women’s Coalition, a political party promoting women in peace building, she was elected to the NI Assembly in 1998. She currently campaigns for Northern Ireland to be granted Honorary EU Association as a European Place of Global Peace building Charlotte Isaksson Gender Advisor, European External Action Service Charlotte has primarily worked with gender and Women, Peace and Security (WPS) in the domain of Security and Defence, including operations and missions. She is currently working within the European External Action Service (EEAS) in Brussels as a senior expert to the Principal Advisor on Gender Equality, Women's Empowerment and WPS. -

What Does Europe Mean for Your Business?"

Northern Ireland Assembly and Business Trust "What does Europe mean for your business?" 13 May 2014 Northern Ireland Assembly and Business Trust "What does Europe mean for your business?" 13 May 2014 Chairperson: Mrs Judith Cochrane MLA Mrs Cochrane: Good afternoon, ladies and gentlemen. Welcome to this afternoon's meeting of the Assembly and Business Trust. I apologise for our Chair Phil Flanagan, who is not able to be here. I also apologise that I will have to dash away at some point. Being in three places at once is not easy. I am delighted to welcome you to this educational briefing session entitled, "What does Europe mean for your business?". It is a timely event with the European elections next Thursday 22 May. I am delighted that we have such an array of speakers to address us. We will hear, first, from Professor David Phinnemore, a professor of European politics at Queen's University, who will give us an academic perspective. We then have Jane Morrice, vice-president of the European Economic and Social Committee, who will provide an overview of the work of that committee. Colette Fitzgerald, head of the European Commission regional office in Belfast, will also address us. As some point, I believe, Mike Nesbitt MLA, Chair of the OFMDFM Committee, will speak on that Committee's engagement on European matters. Following those presentations, David, Jane and Colette will, I believe, be happy to take questions. I hope you will enjoy the session. Just before I hand over to David, I remind you to complete the feedback questionnaires on your seat before you leave. -

Northern Ireland Peace Initiative

Northern Ireland Peace Initiative JOURNEY TO BELFAST AND LONDON Report and Policy Recommendations by William J. Flynn and George D. Schwab February 1999 Contents • Acknowledgment • Foreword • Policy Recommendations • From Hate to Hope • Conclusion ACKNOWLEDGMENT At the invitation of the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office, a National Committee on American Foreign Policy mission consisting of William J. Flynn, chairman, and George D. Schwab, president, spent a week (November 2-7, 1998) in Belfast discussing the peace process in Northern Ireland and in London where we also discussed U.S. and British global security interests with leading statesmen, politicians, diplomats, and academics. The meetings took place at Stormont Estate, 10 Downing Street, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, the House of Commons, think tanks, and the American embassy in London, among other sites. Before embarking, Dr. Schwab was briefed at the State Department by James I. Gadsden, deputy assistant secretary of state for European and Canadian affairs; James M. Lyons, special adviser to the president and the secretary of state for economic initiatives in Ireland; Katharine E. Koch, special assistant, office of the special adviser to the president and the secretary of state for economic initiatives in Ireland; and Patricia Nelson-Douvelis, Ireland desk officer. Although this report and the policy recommendations it contains focus on Northern Ireland, the material gathered on U.S. and British national security interests will be incorporated in relevant NCAFP publications, including those forthcoming on NATO and the Middle East. The sensitivity of some of the issues discussed led a number of people to request that they not be quoted by name or identified in other ways. -

1 '…For Peace Comes Dropping Slow.' Lessons from the Middle In

‘…for peace comes dropping slow.’ Lessons from the middle in Northern Ireland’s peace process. Tony Craig On August 15, 1998 a terrorist car bomb exploded in the town of Omagh in Northern Ireland killing 29 and injuring over 200. Omagh was the deadliest single bomb attack of Northern Ireland’s Troubles, though it occurred after the Good Friday peace agreement there had been ratified by convincing referendum majorities. Like with the assault on the US Capitol on January 6, 2021, history will primarily teach these events as markers of the end of a particular phase and the beginning of a new one (think 9/11) and certainly events like these offer moments of punctuation that are useful in developing narratives and communicating the past to a wider audience. The problem is however that episodes of conflict and violence can come to dominate our understanding of history to the detriment of other factors, trends and behaviors. They remain of course important, as when people are hurt, suffer or die their deaths have profound effects, and when dramatic events happen people pay attention. This emphasis on history as drama replayed in high contrast however dangerously muddies the wider reality where violence is never the whole picture and government action far from the only or even best response. If we view conflict and violence as the interruption of ordinary life; if we see them as aberrant, local, temporal and discordant, then we can see how push- button responses by the state can actually metastasize problems when applied in the longer term as well as how forebearance, stoicism and trust can be the better response to violent division.