Michael Chaney & the Argenti Business Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015 Annual Results 19 August 2015 Agenda

2015 Annual Results 19 August 2015 Agenda • Merger update and strategic focus Angus McNaughton • Financial results Richard Jamieson Angus McNaughton Richard Jamieson • Portfolio performance Chief Executive Officer CFO and EGM Investments Stuart Macrae • Development update Jonathan Timms • FY16 focus and guidance Stuart Macrae Jonathan Timms Angus McNaughton EGM Leasing EGM Development 2 Merger update and strategic focus Angus McNaughton Cranbourne Park, VIC Merger benefits on track with a strong platform for growth • Strategic focus remains unchanged • Operational cost synergies on track • Over 60% of operational cost savings1 already locked in • Merger financing savings achieved1 with over $100m lower cost • Weighted average cost of debt reduced to 4.2% • Integration is on program • Key operational teams finalised and team co-locations underway • Solid FY15 performance • Statutory net profit of $675.1m • Underlying earnings up 6.2%2 • Development pipeline increased to $3.1b and current projects on or ahead of plan The Myer Centre Brisbane, QLD 1. On a run-rate or annualised basis. 2. On an aggregate basis. 4 Strategic focus remains unchanged Retail real estate • We will own, manage and develop Australian retail assets across the spectrum • Portfolio composition will evolve as developments occur and asset recycling continues Operational excellence • High performance intensive asset management approach • Continuous improvement of systems and processes • Strongly committed to responsible investment and sustainability • Development of a fully -

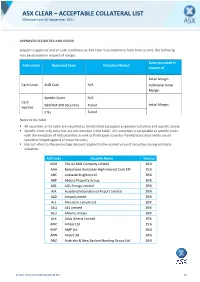

Asx Clear – Acceptable Collateral List 28

et6 ASX CLEAR – ACCEPTABLE COLLATERAL LIST Effective from 20 September 2021 APPROVED SECURITIES AND COVER Subject to approval and on such conditions as ASX Clear may determine from time to time, the following may be provided in respect of margin: Cover provided in Instrument Approved Cover Valuation Haircut respect of Initial Margin Cash Cover AUD Cash N/A Additional Initial Margin Specific Cover N/A Cash S&P/ASX 200 Securities Tiered Initial Margin Equities ETFs Tiered Notes to the table . All securities in the table are classified as Unrestricted (accepted as general Collateral and specific cover); . Specific cover only securities are not included in the table. Any securities is acceptable as specific cover, with the exception of ASX securities as well as Participant issued or Parent/associated entity issued securities lodged against a House Account; . Haircut refers to the percentage discount applied to the market value of securities during collateral valuation. ASX Code Security Name Haircut A2M The A2 Milk Company Limited 30% AAA Betashares Australian High Interest Cash ETF 15% ABC Adelaide Brighton Ltd 30% ABP Abacus Property Group 30% AGL AGL Energy Limited 20% AIA Auckland International Airport Limited 30% ALD Ampol Limited 30% ALL Aristocrat Leisure Ltd 30% ALQ ALS Limited 30% ALU Altium Limited 30% ALX Atlas Arteria Limited 30% AMC Amcor Ltd 15% AMP AMP Ltd 20% ANN Ansell Ltd 30% ANZ Australia & New Zealand Banking Group Ltd 20% © 2021 ASX Limited ABN 98 008 624 691 1/7 ASX Code Security Name Haircut APA APA Group 15% APE AP -

Aurizon Debt Investor Roadshow December 2016

Aurizon Debt Investor Roadshow December 2016 “Aurizon – Australia’s largest rail freight operator” Pam Bains – VP Network Finance (Network CFO) David Collins – VP Finance & Group Treasurer Further information is available online at www.aurizon.com.au Important notice No Reliance on this document This document was prepared by Aurizon Holdings Limited (ACN 146 335 622) (referred to as “Aurizon” which includes its related bodies corporate). Whilst Aurizon has endeavoured to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in this document at the date of publication, it may contain information that has not been independently verified. Aurizon makes no representation or warranty as to the accuracy, completeness or reliability of any of the information contained in this document. Document is a summary only This document contains information in a summary form only and does not purport to be complete and is qualified in its entirety by, and should be read in conjunction with, all of the information which Aurizon files with the Australian Securities Exchange. Any information or opinions expressed in this document are subject to change without notice. Aurizon is not under any obligation to update or keep current the information contained within this document. Information contained in this document may have changed since its date of publication. No investment advice This document is not intended to be, and should not be considered to be, investment advice by Aurizon nor a recommendation to invest in Aurizon. The information provided in this document has been prepared for general informational purposes only without taking into account the recipient’s investment objectives, financial circumstances, taxation position or particular needs. -

Attention ASX Company Announcements Platform. Lodgement of Open Briefing

Attention ASX Company Announcements Platform. Lodgement of Open Briefing. Wesfarmers Limited Wesfarmers House 40 The Esplanade Perth Western Australia 6000 Date of Lodgement: 17-Nov-2004 Title: Open Briefing. Wesfarmers. Briefing Day Discussion The content of this Open Briefing reflects management and analyst discussion at the Wesfarmers Briefing Day held in Sydney on Thursday November 11, 2004. General Corporate Issues corporatefile.com.au Wesfarmers seems to be a little more conservative than other companies on the macro outlook for some of its industries. BHP, for example, seems a lot more bullish. Is there a risk Wesfarmers misses out on some good projects if you are too conservative? Michael Chaney, CEO Wesfarmers We often think about this issue and we’re continually reviewing our assumptions but I’m confident that we haven’t been too conservative. I believe that our assumptions are broadly similar to companies such as BHP for example. Projects or companies are often valued differently by different parties because of strategic considerations rather than different pricing assumptions. Although we have missed opportunities over the years, we’ve still recorded the highest TSR on the ASX over 20 years. Investors should be confident with our management team because we have entrenched and strict valuation disciplines and methodologies. We’ll miss out on more opportunities but enough opportunities should come up to maintain our shareholder returns. corporatefile.com.au Coal prices will fall at some stage. Will that influence you to take a more conservative stance on dividends in the next couple of years in order to avoid the possibility of having to cut dividends after coking prices fall? 1 Michael Chaney I don’t think so because that would be inconsistent with our dividend policy which is to always pay out 100% of our franking credits. -

Amazon Coming to a Car Yard Near You: Cole

Amazon coming to a car yard near you: Cole Digital ‘story teller’ Jeff Cole, right, with David Evans. ‘Eventually (Jeff Bezos) will sell every new automobile in North America’ October 7, 2018 By DAMON KITNEY, STUART McEVOY Amazon could be set to transform another industry He calls himself a “story teller” of the digital world. His clients think he can see into the future. Jeffrey Cole has spent more than three decades advising governments and many of the world’s largest and most successful companies on their digital strategies. In Australia those companies have included Telstra, Wesfarmers, Westpac and the other big banks. Amazon coming to a car yard near you: Cole !2 These days he is a member of the investment committee of the listed Evans & Partners Global Disruption Fund, which now has over $400 million under management and ambitions to grow that to $1 billion in the short to medium term. The fund has just completed an $8m capital raising to provide liquidity for new unit holders. Ask Cole the next industry in the world to be “Amazoned” — that is, disrupted and transformed by Jeff Bezos’s global tech colossus — and his answer is instant. “I think eventually he will sell every new automobile in North America. A lot of manufacturers feel they are saddled to their dealers. A lot of them now want to get rid of the dealer relationship. Tesla, for instance, does not have dealerships. I think you will see Amazon go to manufacturers and say ‘Get out of the dealership business’, and turn the dealerships into service centres,’’ the fast-talking American tells The Australian during a visit to Australia from his US base. -

Investor Briefing Presentation

Investor Briefing 14 October 2008 Westin Hotel, Sydney Richard Goyder Managing Director, Wesfarmers Limited 2 Agenda 8:45 Business Overview 9:15 Coles 10:30 Morning Tea 11:15 Home Improvement & Office Supplies 12:00 Target 12:30 Resources 1:00 Lunch 2:00 Insurance 2:30 Industrial Businesses 3:00 Capital Management 3:10 Q&A 3 Management Team Managing Director & CEO Richard Goyder Finance Director Gene Tilbrook Divisional Managing Directors Home Improvement & Office Supplies John Gillam Coles Ian McLeod Target Launa Inman Kmart Guy Russo ` Insurance Rob Scott Director Industrial Divisions Keith Gordon Resources Stewart Butel Chemicals & Fertilisers Ian Hansen Industrial & Safety Olivier Chretien Energy Tim Bult 4 Group Overview • An uncertain global environment • Strong businesses • Focus on running businesses well – Return on capital – Effect turnarounds • Balance sheet management • Long term approach, consistent strategies 5 Renewal of Coles Ian McLeod 6 Encouraging underlying performance • Improving food and liquor customer numbers – Availability improving – Reduction in central costs – Stronger promotional focus (non-repeat of value destroying activity) • Food & Liquor Qtr 1 total sales growth 2.6%, comparable sales growth 1.3% • Solid growth in Convenience – Winner of “convenience retailer of the year”* – Qtr 1: total shop sales growth 7.0%, comparable shop sales growth 4.6% *Awarded by Australasian Association of Convenience Stores 7 Starting point … A cost cutting strategy • Previously, Coles managed to a short-term EBIT target Boom / • Bureaucratic, top heavy management bust sales structure & margin tactics • Lack of cohesive strategy Customer Cutback confusion on cost • Inward facing, not customer focused • Store focus on costs first, sales second! • Chronic underinvestment / infrastructure decay Promotional Poor chaos quality But…. -

2007-Sustainability-Report.Pdf

Sustainability 07 COVER We are one of Australia’s largest public companies with our head office in Perth, Western Australia. In 1984 we listed on what is now the Australian Securities Exchange, having begun as a farmers’ cooperative in 1914. Our major operating business interests SustainSustainabilityability 07 are in home improvement products and building supplies; coal mining; insurance; industrial and safety products; chemicals and fertilisers; gas processing and distribution and power supply. Home Industrial & Chemicals & Other Coal Insurance Energy Improvement Safety Fertilisers Businesses BUNNINGS CURRAGH LUMLEY AUSTRALIA CSBP COREGAS GRESHAM (AUST/NZ) GENERAL PARTNERS BLACKWOODS INSURANCE (50%) PREMIER AUSTRALIAN WESFARMERS Members of the Wesfarmers (AUST) PROTECTOR Ultimate Challenge at sea off HOUSEWORKS GOLD LPG ALSAFE REAGENTS WESPINE BENGALLA Fremantle. LUMLEY (75%) INDUSTRIES (40%) BULLIVANTS KLEENHEAT GENERAL (50%) GAS Read about it on page 8. INSURANCE MULLINGS QUEENSLAND (NZ) FASTENERS NITRATES BUNNINGS ENERGY MOTION (50%) WAREHOUSE GENERATION WESFARMERS INDUSTRIES PROPERTY (ENGEN) FEDERATION TRUST INSURANCE (23%) NEW ZEALAND AIR LIQUIDE CONTENTS WA OAMPS BLACKWOODS (40%) (AUST/UK) PAYKELS Managing Director’s Welcome 1 NZ SAFETY CROMBIE PROTECTOR About This Report 2 LOCKWOOD SAFETY (NZ) PACKAGING HOUSE Sustainability Scorecard 4 KOUKIA (91%) Bunnings 12 Curragh 24 Premier Coal 32 Kleenheat Gas 44 Wesfarmers LPG 52 Industrial & Safety 60 CSBP 70 Insurance 82 Other Businesses 90 Independent Assurance Statement 94 Glossary and Feedback 96 AREAS COVERED 1 WELCOME This is the tenth time we’ve given an account of our performance across a range of issues relevant to our pursuit of a sustainable future. We have made very clear the priority we The Last 12 Months Looking Ahead allocate to this goal by adopting, as one of just Since we last reported there’s been an intense As ever, we must continue to improve. -

Letter to Shareholders

30 November 2018 LETTER TO SHAREHOLDERS In accordance with ASX Listing Rule 3.17.1, enclosed is a copy of a letter being sent today to shareholders who hold Coles Group Limited shares on the Australian Securities Exchange. Yours sincerely Daniella Pereira Company Secretary Coles Group Limited Coles Group Limited ABN 11 004 089 936 800 Toorak Road Hawthorn East Victoria 3123 Australia PO Box 2000 Glen Iris Victoria 3146 Australia Telephone +61 3 9829 5111 www.colesgroup.com.au Update your information: Online: : www.investorcentre.com/col By Mail: * Computershare Investor Services Pty Limited GPO Box 2975 Melbourne Victoria 3001 Australia Enquiries: (within Australia) 1300 171 785 (international) +61 3 9415 4078 Facsimile +61 3 9473 2500 [email protected] Securityholder Reference Number (SRN) I *L000005* Important: Dear Shareholder Demerger of Coles Group Limited (Coles) from Wesfarmers Limited (Wesfarmers) On behalf of the Board of Coles, I am pleased to welcome you as a Coles shareholder. Coles is a leading Australian retail company with a proud history. Originally founded by G.J. Coles in 1914, we have served generations of Australian families with the best quality, service and value for over 100 years. We enjoy a leading position because our customers trust Coles to provide them with everyday products including fresh food, groceries, household goods, liquor, fuel and financial services through our store network and online platforms. Coles processes more than 21 million customer transactions on average each week, employs over 115,000 team members, works with over 7,000 suppliers and operates more than 2,500 retail outlets nationally. -

Information Memorandum NZ Finance Holdings Pty Limited

Information Memorandum and NZ Finance Holdings Pty Limited A$4,000,000,000 Note Programme Notes issued are unconditionally guaranteed by Wesfarmers Limited and certain of its subsidiaries Australian Dealers for electronic promissory notes, short term notes and medium term notes issued by Wesfarmers Limited Australia and New Zealand Banking Commonwealth Bank of Australia Group Limited (ABN 48 123 123 124) (ABN 11 055 357 522) National Australia Bank Limited Westpac Banking Corporation (ABN 12 004 044 937) (ABN 33 007 457 141) New Zealand Dealers for short term notes and medium term notes issued by NZ Finance Holdings Pty Limited ANZ Bank New Zealand Limited Bank of New Zealand Commonwealth Bank of Australia (acting Westpac Banking Corporation (acting through its New Zealand Branch) through its New Zealand Branch) (ABN 48 123 123 124) (ABN 33 007 457 141) Warning for New Zealand Investors pursuant to $750,000 minimum investment wholesale investor exclusion The law normally requires people who offer financial products to give information to investors before they invest. This requires those offering financial products to have disclosed information that is important for investors to make an informed decision. The usual rules do not apply to this offer because there is an exclusion for offers where the amount invested upfront by the investor (plus any other investments the investor has already made in the financial products) is $750,000 or more. As a result of this exclusion, you may not receive a complete and balanced set of information. You will also have fewer other legal protections for this investment. -

2019 Annual Report 1 2019 the YEAR in REVIEW

Wesfarmers Annual Report Annual Wesfarmers 2019 2019 WESFARMERS ANNUAL REPORT ABOUT WESFARMERS ABOUT THIS REPORT All references to ‘Indigenous’ people are intended to include Aboriginal and/or From its origins in 1914 as a Western This annual report is a summary Torres Strait Islander people. Australian farmers’ cooperative, Wesfarmers of Wesfarmers and its subsidiary Wesfarmers is committed to reducing the has grown into one of Australia’s largest companies’ operations, activities and environmental footprint associated with listed companies. With headquarters in financial performance and position as at the production of this annual report and Perth, Wesfarmers’ diverse businesses in this 30 June 2019. In this report references to printed copies are only posted to year’s review cover: home improvement; ‘Wesfarmers’, ‘the company’, ‘the Group’, shareholders who have elected to receive apparel, general merchandise and office ‘we’, ‘us’ and ‘our’ refer to Wesfarmers a printed copy. This report is printed on supplies; an Industrials division with Limited (ABN 28 008 984 049), unless environmentally responsible paper businesses in chemicals, energy and otherwise stated. manufactured under ISO 14001 fertilisers and industrial safety products. Prior References in this report to a ‘year’ are to environmental standards. to demerger and divestment, the Group’s the financial year ended 30 June 2019 businesses also included supermarkets, unless otherwise stated. All dollar figures liquor, hotels and convenience retail; and are expressed in Australian -

Workers' Compensation Self-Insurer Contact List

List of Workers' Compensation Insurers Information correct as at 14 September 2021 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ WORKCOVER QUEENSLAND GPO Box 2459 Brisbane QLD 4001 AUSTRALIA P: 1300 362 128 F: 1300 651 387 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ SELF INSURERS Aged Care Employers Self-Insurance Group Arnott's Biscuits Limited Aurizon Operations Limited Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited BHP Group Limited Brisbane City Council CSR Limited Coles Group Limited Council of the City of Gold Coast Glencore Queensland Limited Healius Limited Inghams Enterprises Pty Limited JBS Australia Pty Limited Liberty Holdings Australia Ltd Local Government Workcare Qantas Airways Limited Queensland Rail Limited Redland City Council South32 Cannington Proprietary Limited Teys Australia Meat Group Pty Ltd The Star Entertainment Group Limited Workers' Compensation Self Insurer Contact List - as at 14 September 2021 Page 1 The University of Queensland Toll Holdings Limited Townsville City Council Wesfarmers Limited Westpac Banking Corporation Wilmar Sugar Pty Ltd Woolworths Group Limited Workers' Compensation Self Insurer Contact List - as at 14 September 2021 Page 2 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ SELF-INSURANCE LICENCE: Aged Care Employers Self-Insurance Group COMMENCEMENT DATE: 1 January 2005 ADDRESS: TriCare Ltd 250 Newnham Road PO Box 439 MT -

13 August 2007

3 July 2008 CHAIRMAN TO STEP DOWN AT ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING Mr Trevor Eastwood AM today announced he would be stepping down as Chairman of Wesfarmers Limited at the company’s Annual General Meeting in November 2008. To ensure a smooth transition to a new Chairman, the Wesfarmers Board has appointed Dr Bob Every as its Deputy Chairman. Dr Every joined the Wesfarmers Board in February 2006 and will take up the position of Chairman after the Annual General Meeting on 13 November. Dr Every was formerly Chief Executive and Managing Director of OneSteel, President of BHP Steel, Managing Director of Tubemakers of Australia Limited and a former Chairman of Steel & Tube Holdings Limited in New Zealand. He is currently Chairman of Iluka Resources, on the Board of Boral Limited and a Director of Malcolm Sargent Cancer Fund for Children in Australia Limited, also known as Redkite. Mr Eastwood, who has been Chairman of Wesfarmers since 2002, said it was an appropriate time for him to retire after six years in the role, as the company proceeds through a significant new era of opportunity and change. “I have been extremely fortunate to have been Chairman during a time of tremendous growth and transition for the company,” Mr Eastwood said. “Transformation of the group into a truly national enterprise has accelerated, particularly over the past year with the acquisition of the Coles Group. “As Chairman, Board Member and a former Managing Director I’m proud to have been involved in these and other major changes that have seen the former co-operative become Australia’s biggest private sector employer, with 200,000 employees, and more than 470,000 shareholders.