Escapements of Chinook Salmon in Southeast Alaska And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Haines Highway Byway Corridor Partnership Plan

HAINES HIGHWAY CORRIDOR PARTNERSHIP PLAN 1 Prepared For: The Haines Borough, as well as the village of Klukwan, and the many agencies, organizations, businesses, and citizens served by the Haines Highway. This document was prepared for local byway planning purposes and as part of the submission materials required for the National Scenic Byway designation under the National Scenic Byway Program of the Federal Highway Administration. Prepared By: Jensen Yorba Lott, Inc. Juneau, Alaska August 2007 With: Whiteman Consulting, Ltd Boulder, Colorado Cover: Haines, Alaska and the snow peaked Takhinska Mountains that rise over 6,000’ above the community 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION..............................................................5-9 2. BACKGROUND ON Byways....................................11-14 3. INSTRINSIC QUALITY REVIEW..............................15-27 4. ROAD & TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM...................29-45 5. ToURISM & Byway VISITATION...........................47-57 6. INTERPRETATION......................................................59-67 7. PURPOSE, VISION, GOALS & OBJECTIVES.......69-101 8. APPENDIX..................................................................103-105 3 4 INTRODUCTION 1 Chilkat River Valley “Valley of the Eagles” 5 The Haines Highway runs from the community byway. Obtaining national designation for the of Haines, Alaska to the Canadian-U.S. border American portion of the Haines highway should station at Dalton Cache, Alaska. At the half way be seen as the first step in the development of an point the highway passes the Indian Village of international byway. Despite the lack of a byway Klukwan. The total highway distance within Alaska program in Canada this should not prevent the is approximately 44 miles, however the Haines celebration and marketing of the entire Haines Highway continues another 106 miles through Highway as an international byway. -

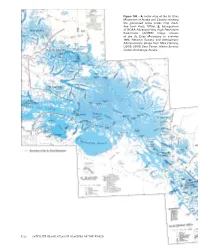

A, Index Map of the St. Elias Mountains of Alaska and Canada Showing the Glacierized Areas (Index Map Modi- Fied from Field, 1975A)

Figure 100.—A, Index map of the St. Elias Mountains of Alaska and Canada showing the glacierized areas (index map modi- fied from Field, 1975a). B, Enlargement of NOAA Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) image mosaic of the St. Elias Mountains in summer 1995. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration image from Mike Fleming, USGS, EROS Data Center, Alaska Science Center, Anchorage, Alaska. K122 SATELLITE IMAGE ATLAS OF GLACIERS OF THE WORLD St. Elias Mountains Introduction Much of the St. Elias Mountains, a 750×180-km mountain system, strad- dles the Alaskan-Canadian border, paralleling the coastline of the northern Gulf of Alaska; about two-thirds of the mountain system is located within Alaska (figs. 1, 100). In both Alaska and Canada, this complex system of mountain ranges along their common border is sometimes referred to as the Icefield Ranges. In Canada, the Icefield Ranges extend from the Province of British Columbia into the Yukon Territory. The Alaskan St. Elias Mountains extend northwest from Lynn Canal, Chilkat Inlet, and Chilkat River on the east; to Cross Sound and Icy Strait on the southeast; to the divide between Waxell Ridge and Barkley Ridge and the western end of the Robinson Moun- tains on the southwest; to Juniper Island, the central Bagley Icefield, the eastern wall of the valley of Tana Glacier, and Tana River on the west; and to Chitistone River and White River on the north and northwest. The boundar- ies presented here are different from Orth’s (1967) description. Several of Orth’s descriptions of the limits of adjacent features and the descriptions of the St. -

HAINES HIGHWAY CORRIDOR Partnership PLAN

HAINES HIGHWAY CORRIDOR PARTNERSHIP PLAN 1 Prepared For: The Haines Borough, as well as the village of Klukwan, and the many agencies, organizations, businesses, and citizens served by the Haines Highway. This document was prepared for local byway planning purposes and as part of the submission materials required for the National Scenic Byway designation under the National Scenic Byway Program of the Federal Highway Administration. Prepared By: Jensen Yorba Lott, Inc. Juneau, Alaska August 2007 With: Whiteman Consulting, Ltd Boulder, Colorado Cover: Haines, Alaska and the snow peaked Takhinska Mountains that rise over 6,000’ above the community 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION..............................................................5-9 2. BACKGROUND ON Byways....................................11-14 3. INSTRINSIC QUALITY REVIEW..............................15-27 4. ROAD & TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM...................29-45 5. ToURISM & Byway VISITATION...........................47-57 6. INTERPRETATION......................................................59-67 7. PURPOSE, VISION, GOALS & OBJECTIVES.......69-101 8. APPENDIX..................................................................103-105 3 4 INTRODUCTION 1 Chilkat River Valley “Valley of the Eagles” 5 The Haines Highway runs from the community byway. Obtaining national designation for the of Haines, Alaska to the Canadian-U.S. border American portion of the Haines highway should station at Dalton Cache, Alaska. At the half way be seen as the first step in the development of an point the highway passes the Indian Village of international byway. Despite the lack of a byway Klukwan. The total highway distance within Alaska program in Canada this should not prevent the is approximately 44 miles, however the Haines celebration and marketing of the entire Haines Highway continues another 106 miles through Highway as an international byway. -

Chart 5-25 Haines Event Visitors, 2008-2011

Despite receiving few cruise ships in port, Haines benefits from the Skagway cruise ship port of call because Haines businesses and the HCVB worked to develop opportunities for cruise passengers to visit Haines during their stay in Skagway. In 2011, approximately 28,500 cruise ship passengers visited Haines via fast day ferry between Skagway and Haines to do day excursions in Haines. These visitors spent an average of $135 per person in Haines during their stay in 2011, or $3.8 million (2011 Haines Cruise and Fast Ferry Passenger Survey, McDowell Group). Dependable fast day boat runs between these communities is essential to capture this business. The Haines Borough’s Convention and Visitor Bureau has partnered with community organizations and businesses to actively create destination events and market them. The Haines Chamber of Commerce’s annual events calendar lists a number of activities that attract nearly 15,000 independent visitors annually (Chart 5-25). The largest of these is the multi-day Southeast Alaska State Fair that features live music, food, arts and crafts, farm animals, and amusement rides. In 2011, this event attracted 11,500 people. The next largest event is the 148 mile Kluane Chilkat International Bike Race in June, popular with local, Juneau and Whitehorse residents. Chart 5-25 Haines Event Visitors, 2008-2011 15,000 12,500 10,000 7,500 5,000 2,500 - 2008 2009 2010 2011 SE Fair Spring Fling 187 187 187 187 Eagle Festival 271 266 Alaska Brew Fest 665 683 953 1,009 Kluane Bike Race 1,200 1,041 1,282 1,223 SE State Fair 10,000 10,000 11,000 11,500 HAINES BOROUGH 2025 COMPREHENSIVE PLAN / September 2012 page 92 The opportunities for recreation related tourism are deep in the community with access to so many varied outdoor settings. -

ALASKA FISH FACTOR Laine Welch/Fish Factor Note That All of These Applications Were for to DNR

Residents oppose Roadless Rule - page 3 TWC leaves mining committee - page 4 Serving Haines and Klukwan, Alaska since 1966 Chilkat Valley News Volume XLVIV, Issue 49 Thursday, December 12, 2019 $1.25 Lack of snow masks DOT overtime cuts By Kyle Clayton of Southeast shares one budget, Last Thursday’s snow-covered and one pool of overtime hours. roads in the late afternoon and Boron doesn’t have a fixed amount evening shined a light on what of overtime hours to work with, but plowing will look like on the Haines relies on his boss to tell him what Highway and other state roads if the percentage has been spent. borough experiences a normal winter. Designating overtime for plowing, On Thursday Dec. 5, a foot of Boron said, is a tough judgement snow had fallen in town, according call. If he plowed on a Thursday to NOAA data. Because the Alaska morning, for example, he likely Department of Transportation cut won’t plow in the afternoon in order overtime hours for its workers, plow to save overtime for the weekend if truck drivers were off work Thursday necessary. by the time parents were picking their “My overtime is severely children up from the Haines School. restricted,” Boron said. “It’s very Haines DOT station foreman unlikely I would do overtime plowing Matt Boron said drivers typically on the afternoon on a work week. I start plowing around 5 a.m. so that would save it for the weekend.” they can clear Main Street and other He said he’d never use overtime high traffic areas before the morning on lower priority roads like Mud commute. -

Pamphlet to Accompany Scientific Investigations Map 3253

Prepared for the National Park Service Marine Benthic Habitat Mapping of the West Arm, Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve, Alaska By Timothy O. Hodson, Guy R. Cochrane, and Ross D. Powell Pamphlet to accompany Scientific Investigations Map 3253 2013 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Setting ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Geology ................................................................................................................................................................................ 3 Temperate Glacimarine Environment ................................................................................................................................... 3 Oceanography ...................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Previous Habitat Mapping in Glacier Bay ................................................................................................................................ -

Deep Benthic Coral Habitats of Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve, Alaska Elise C

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library Summer 8-23-2019 Deep Benthic Coral Habitats of Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve, Alaska Elise C. Hartill University of Maine, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Marine Biology Commons, and the Other Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Hartill, Elise C., "Deep Benthic Coral Habitats of Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve, Alaska" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2996. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/2996 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEEP BENTHIC CORAL HABITATS OF GLACIER BAY NATIONAL PARK AND PRESERVE, ALASKA By Élise Catherine Hartill B.Sc. University of Maine, 2017 A THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science (in Marine Biology) The Graduate School The University of Maine August 2019 Advisory Committee: Rhian Waller, Associate Professor of Marine Science, Advisor Peter Auster, Research Professor Emeritus of Marine Sciences, University of Connecticut Damian Brady, Associate Professor of Oceanography Brenda Hall, Professor School of Earth and Climate Sciences and Climate Change Institute DEEP BENTHIC CORAL HABITATS OF GLACIER BAY NATIONAL PARK AND PRESERVE, ALASKA By Élise Catherine Hartill Thesis Advisor: Dr. Rhian Waller An Abstract of the Thesis Presented In Partial Fulfillments of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science (in Marine Biology) August 2019 Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve in Southeast Alaska is a system of fjords that presents an ideal natural laboratory to study terrestrial, aquatic and marine patterns of succession due to its unique and recent history of deglaciation. -

Marine Benthic Habitat Mapping of Muir Inlet, Glacier Bay National

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping 2010 Marine Benthic Habitat Mapping of Muir Inlet, Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve, Alaska With an Evaluation of the Coastal and Marine Ecological Classification Standard III Luke D. Mitchell Northern Illinois University Guy R. Cochrane Lisa Etherington Ross D. Powell Northern Illinois University Larry A. Mayer University of New Hampshire, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/ccom Part of the Oceanography and Atmospheric Sciences and Meteorology Commons Recommended Citation Trusel, Luke D., Cochrane, Guy R., Etherington, Lisa L. Powell, Ross D., and Mayer, Larry A., 2010, Marine benthic habitat mapping of Muir Inlet, Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve, Alaska, with an evaluation of the Coastal and Marine Ecological Classification Standard III: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Map 3122, 4 sheets, various scales, 1 pamphlet, 26 p. This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Prepared for the National Park Service Marine Benthic Habitat Mapping of Muir Inlet, Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve, Alaska With an Evaluation of the Coastal and Marine Ecological Classification Standard III By Luke D. Trusel, Guy R. Cochrane, Lisa L. Etherington, Ross D. -

Alaska Fish Factor

Chilkoot project delayed - page 5 Borough borrows for sewer project - page 6 Named Alaska’s Best Weekly Newspaper, 2013 and 2014 Chilkat Valley News Volume XLV Number 23 Thursday, June 11, 2015 $1 No room Pair convicted at the inn in car break-ins By Karen Garcia The state has secured two convictions in connection at border with the ransacking of 30 cars downtown two years ago, but some victims this week said that’s not justice By Tom Morphet enough. Motorists stranded in Canada Blake Ward and Austin Hotch each recently pleaded after the nighttime closure of guilty to theft charges. Ward, 21, pleaded guilty to third- Canada Customs should contact degree theft for possessing a GoPro stolen during the the RCMP in Haines Junction, Y.T. June 2013 spree. Hotch, 20, pleaded guilty to fourth- if they need help, a spokesperson degree theft for possessing a stolen camera. for the Canada Border Service Other items taken from unlocked cars included cash, Agency said this week. credit cards, prescription medication, tools, binoculars, The question arose when Haines stereo equipment, electronics, cameras, ammunition summer resident Kerry McIver, and driver’s licenses. a 29-year-old school teacher, Each man received 30 days in jail and was ordered became stranded at the Canada to pay restitution. Customs station and was left Although Ward and Hotch were found guilty only taking shelter for the night in a of theft charges relating to two cameras, the 30-day jail parked trucker’s cab early June 4. sentence reflected acknowledgement of a much larger, McIver said that due to a wide-ranging crime, said district attorney Amy Paige. -

By Edward F. Bugliosi

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY HYDROLOGIC RECONNAISSANCE OF THE CHILKAT RIVER BASIN, SOUTHEAST ALASKA With Special Reference to the Bald Eagle Critical Habitat at the Tsirku River A.lluvia1 Fan By Edward F. Bugliosi U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Open-File Report 84-618 Prepared in cooperation with the ALASKA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF GEOLOGICAL AND GEOPHYSICAL SURVNS Anchorage, Alaska 1985 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR WILLIAM P, CLARK, SECRETARY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director Far additional information Copies of this report can write to: be purchased from: District Chief Open-File Services Section U.S. Geological Survey Western Distribution Branch Water Resources Division U.S. Geological Survey 4230 University Drive, Suite 201 Box 25425, Federal Center Anchorage, Alaska 99508-4664 Denver, Colorado 80225 (907) 271-4138 (303) 234-5888 CONTENTS Page Abstract ............................................................... Introduction........................................................... Acknowledgments ......,,,..................................e..0.... Physiography ...................................................... Climate ........................................................... Geology ................................................................ Geomorphic and glacial history.. ....................................... surface water . ............................................... Chilkat I ................................................... Streamflow ....................................................... -

Haines Highway Scenic B Y

aines ighway H Master Interpretive Plan H cenic y way S B S A E L C A S R K U A O S D E E R P A L R A T R M E T U N T O F N A Prepared for: Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities, State Scenic Byways Program Prepared by: Alaska Department of Natural Resources, Division of Parks and Outdoor Recreation, Interpretation and Education Funded by: Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities and a National Scenic Byways Grant from the Federal Highway Administration aines ighway H Master Interpretive Plan H cenic y way S B Apple tree at Charles Anway’s Cabin Table of Contents Contents 1 Introduction . 1 6 . Recommendations . 23 What is a National Scenic Byway? . 1 Personal Interpretation ..........................................24 Purpose and Need ..............................................1 Non-Personal Interpretation .....................................24 Planning Process ...............................................2 Byway Welcome Panels . 24 Goals and Objectives . 3 Site Orientation Panels .....................................25 2 Overview of Resources . 7 Tlingit Place Names ........................................27 Natural Qualities. 7 Recommended New Interpretive Waysides ........................28 Scenic Qualities ................................................8 Three Guardsmen Mountain Totem Poles ..........................29 Historic Qualities ...............................................9 7 . Design Guidelines . 30 Recreational Qualities ...........................................10 Panel -

Deep Coral Habitats of Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve, Alaska

PLOS ONE RESEARCH ARTICLE Deep coral habitats of Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve, Alaska 1 1,2 3,4 EÂ lise C. HartillID *, Rhian G. Waller , Peter J. Auster 1 Darling Marine Center, School of Marine Sciences, University of Maine, Walpole, Maine United States of America, 2 Sven LoveÂn Centre, TjaÈrnoÈ, University of Gothenburg, StroÈmstad, Sweden, 3 Department of Marine Sciences, University of Connecticut, Groton, Connecticut, United States of America, 4 Mystic Aquarium±Sea Research Foundation, Mystic, Connecticut, United States of America a1111111111 * [email protected] a1111111111 a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract a1111111111 Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve (GBNPP) in Southeast Alaska is a system of glaci- ated fjords with a unique and recent history of deglaciation. As such, it can serve as a natural laboratory for studying patterns of distribution in marine communities with proximity to gla- cial influence. In order to examine the changes in fjord-based coral communities, underwa- OPEN ACCESS ter photo-quadrats were collected during multipurpose dives with a remotely operated Citation: Hartill EÂC, Waller RG, Auster PJ (2020) Deep coral habitats of Glacier Bay National Park vehicle (ROV) in March of 2016. Ten sites were chosen to represent the geochronological and Preserve, Alaska. PLoS ONE 15(8): e0236945. and oceanographic gradients present in GBNPP. Each site was surveyed vertically between https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236945 100 and 420 meters depth and photo-quadrats were extracted from the video strip transects Editor: Andrew Davies, University of Rhode Island, for analysis. The ROV was equipped with onboard CTD which recorded environmental data UNITED STATES (temperature and salinity), in order to confirm the uniformity of these characteristics at depth Received: February 26, 2020 across the fjords.